But first, links to my blog posts about four stories presented in Blood 20 that I have already read:

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

Tanith Lee: "Il Bacio (Il Chiave)," "The Beautiful Biting Machine" and "The Isle is Full of Noises"

Friday, July 16, 2021

From the Feb '33 issue of Weird Tales: H B Cave, C A Smith, H P Lovecraft & A Derleth

"The Cult of the White Ape" by Hugh B. Cave (1933)

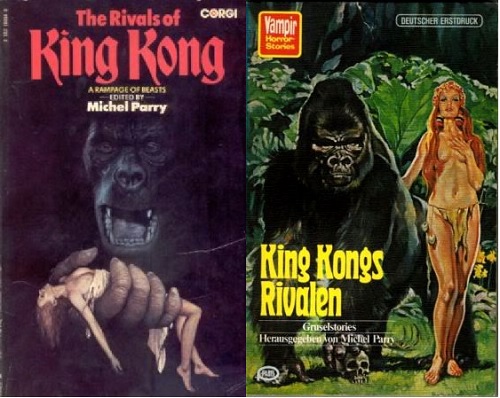

"The Cult of the White Ape" has been reprinted in numerous places, like Keep on the Light (less than a year after it appeared in Weird Tales) and Michel Parry's The Rivals of King Kong (in 1978) so I'm thinking this might be a good one. Anyway, I love the idea of a killer ape--the 1933 King Kong is my favorite movie, beating out even such classics as The Driller Killer, Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key and Gamera vs Guiron in the MPorcius film pantheon--so I am starting this blog post with high hopes!This novelette (14 pages here in Weird Tales) is a memoir by an administrator in the Belgian Congo, Varicks, the only white man in a remote village deep in a jungle where it is always raining. He tells us what happened when a white couple, oafish fat drunk Betts and his pretty young wife Lucilia, moved into the area to start a rubber tree plantation. The drunken Betts immediately trips over the local witch doctor, a deformed man with filed teeth who is reclining on the veranda of Varicks's dwelling, and then brutally kicks him. Betts is also physically abusive to his native employees and to his wife, and even plants some of his rubber trees in a clearing said to be sacred to a secretive cult of lycanthropes.

The rubber planter goes increasingly crazy as the story progresses. When he beats two workers to death the narrator goes to arrest him, but Betts, absolutely mad, overpowers Varicks and carries the administrator and Lucilia to that sacred clearing, binding them in front of the tower at the clearing's center. Naked, the maniac, moving like an ape, dances around and around the tower. When moonlight falls on the tower (Cave I think makes a mistake, having the moonlight touch the bottom of the tower before the apex) the insane planter moves to kill his captives! Amazingly, they are rescued by a pack of white apes bigger than gorillas! These apes are joined by snakes and great cats and reptiles, apparently local inhabitants in their lycanthropic forms; the white ape who carries Varicks and Lucilia to safety is the witch doctor in his animal form, doing Varicks a solid because he has always tried to be a fair administrator--he tended to the witch doctor's injuries after Beets kicked him, for example. Beets is killed and apparently eaten, and the narrator and Lucilia lose consciousness, waking up back in the village. Varicks quits his job and leaves the jungle and he and Lucilia get married.

"The Cult of the White Ape" kind of reminds me of those Somerset Maugham stories about two white guys in a colony, one of whom knows how to correctly deal with the natives while the other doesn't; lots of Maugham stories of this type also feature love triangles, as Cave's story here does. "The Cult of the White Ape" isn't very well-written, but I guess reaches the level of "acceptable," and the plot is not bad. The story is never boring, being full of violence and blood, and the author's treatment of the black Africans is interesting--they are obviously very alien, but are portrayed as essentially sympathetic, as victims and as meters out of justice; in the last line of the story Varicks tells us that the witch doctor is "wiser by far than any of us."

A passing grade for this one.

"The Mandrakes" by Clark Ashton Smith (1933)

This is one of Smith's stories of the French province of Averoigne. In the fifteenth century, there live a wizard and a witch, a married couple who, in their hut on the edge of a village, make and sell love potions. Ironically, their marriage is not too good--the witch is violent and impossible to get along with. One day she attacks the wizard with a knife and in the resulting fight he kills her. The wizard buries her body under a bed of mandrake plants. When he harvests the mandrake roots for his potions some months later he finds the roots, which often somewhat resemble a human form, to be shockingly accurate representations of his dead wife's body! When he cuts them they writhe and bleed! He uses them to make potions anyway, and these love potions have a calamitous effect on all who imbibe them! The villagers who tolerated the wizard's illegal trade when he provided them wares that facilitated their love affairs now turn on him and the authorities exact the ultimate penalty!A brief and well crafted story with lots of fun horror and supernatural elements. Thumbs up! "The Mandrakes" would be reprinted in numerous Smith collections and in one of those Stefan Dziemianowicz, Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Weinberg anthologies put out by Barnes & Noble.

"The Cats of Ulthar" by H. P. Lovecraft (1920)

This quite brief piece, according to isfdb part of Lovecraft's "Dream Cycle," first appeared in the amateur press publication Tryout and was reprinted in Weird Tales in 1926 and again in this 1933 issue.In a town in some fantasy land live a couple who hate cats and capture and murder any who come into their yard. The cat-loving townspeople are too scared of this couple to do anything about it, but one day a caravan of what we might call gypsies if we forgot we weren't supposed to say that anymore comes to town. When a cat who is the comfort of an orphan among the travelers' ranks is (apparently) killed by the sinister couple the child calls upon the travelers' gods and after the caravan has left the cats of the town unite to eat the cat-killing couple.

"The Cats of Ulthar" has a tone sort of like a fairy tale, and I have to admit I prefer those Lovecraft stories that are presented in the form of first-person narratives and/or news clippings and scientific reports. This story is just OK; presumably a lot of people connect to the story because they love cats, the way I connect to a story like Smith's "The Mandrakes" because it is about a topic close to my heart, the disastrous sexual relationship.

As you might expect, besides appearing in three billion Lovecraft collections, "The Cats of Ulthar" has been included in several cat anthologies.

|

| I almost didn't include these covers in the blog post because they are so bad, but decided that they are bad in a way that excites laughter and so may add entertainment value to MPorcius Fiction Log. |

"The Vanishing of Simmons" by August Derleth (1933)

If isfdb is to be believed, this story has never been reprinted, so I am readying myself for a total disaster.

Efficiency expert and amateur investigator into the occult John Simmons has vanished, and the narrator, a medical man and friend of Simmons named Sexton, tells us how it happened.

Simmons's father, the Major, had a big estate near Richmond. Jennie, a young "mulatto" woman worked there, as did Jennie's mother. Simmons found Jennie attractive, but Jennie and Mom left the Major's employ when the Major heard rumors that Jennie was in a voodoo cult and his efforts to get her to abandon the practice of black magic lead to violence between himself and the two women. The Major, a healthy man, died of a heart attack soon after this fracas--could he have been the victim of voodoo?

Simmons sold the estate and moved into town. Jennie's mother showed up one day, selling photographs. Simmons purchased one, a photo of a slender mixed race woman clad in the costume of a voodoo priestess; the figure was facing away from the camera, but Simmons presumed it was Jennie. Simmons hung it up in his home where he could see it all the time and became sort of obsessed with it.

One day Simmons comes to Sexton to say the picture has changed--the woman has turned to face the camera and her face is a grotesque mask of hate! Sexton confirms Simmons's story--the picture has changed, and looking at it is very disturbing. Sexton takes away the picture, but he is too late--Simmons develops a mysterious injury on his chest, which first looks like a bruise and then later like a stab wound. Then he disappears, never to be seen again. When Sexton looks at the photo it has changed again--the woman holds a knife and laying before her on the ground, dead, is Simmons! Sexton throws the horrifying photo into the fire, and some time later learns that Jennie and her mother have been found dead, mysteriously burned to death!

This story feels like something Derleth threw together quickly without carefully thinking it over and without troubling to revise it. There are passages that feel extraneous, like a preamble about "loopholes in natural laws," and others that are needlessly confusing, while some plot points feel disconnected and elements that should have been elaborated on, like Simmons's feelings for Jennie, are given short shrift. The basic idea of voodoo practitioners using a photograph to exact revenge on white people who mistreated them is good, but the fact that Jennie and her mother leave themselves vulnerable to an obvious counter attack--or just an ordinary accident which causes damage to the photo--feels like a plot hole. Also, why does Derleth have the voodoo priestess both kill Simmons through the picture and suck him into the picture? Just one or the other would make more sense and be scarier--for example, if Jennie had imprisoned Simmons in the picture alive, maybe torturing or tormenting him or something, Sexton would face a terrible dilemma: burning the picture might liberate Simmons but also kill him; maybe instead of destroying the photo Sexton would feel impelled to obsessively protect it from Jennie and her cult.

The bones of a good story are here, but not enough work was done to erect those bones and give them life, and as the tale stands I've gotta give "The Disappearance of Simmons" a thumbs down.

**********

Our exploration of 1930s Weird Tales creeps forward on little cat feet, or maybe stomps forward on the paws of righteous apes. Either way, progress on this weird odyssey continues.

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Quest for the White Witch by Tanith Lee

You are a god, Vazkor, son of Vazkor. And you do this thing not only to make a path to a witch's hiding place, but to prove to men what has come among them.Two decades ago, Karrakaz, the only survivor of a long dead race of almost unkillable psychics, awoke after centuries of suspended animation to be heralded as a goddess or a witch by the barbaric nomads and sophisticated city folk she met. Vazkor, the sorcerer and ambitious general, dominated Karrakaz and leveraged her abilities and renown in support of his usurpations and war mongering; the crises he launched shattered the social and political order, and might have made him ruler of a continent, but Karrakaz asserted her independence and turned on him, killing him. Then she was carried away in a flying saucer. Such was the tale described in Tanith Lee's 400-page 1975 novel The Birthgrave.

During all that excitement Vazkor found time to impregnate Karrakaz. Karrakaz was unable to abort Vazkor's child, which had inherited her super durability, so when she gave birth she left the baby boy with some barbarian nomads. That boy's adventures to the age of twenty were described in Lee's 1978 novel of 200 pages, Vazkor, Son of Vazkor. When he realized who his true parents were, Tuvek, as his adoptive tribe had named him, vowed to kill the mother who had abandoned him and killed his father. At the end of Vazkor, Son of Vazkor, he as lead to believe that his mother must be on a distant southern continent he had never before heard of, and set sail for this mysterious land. In Quest for the White Witch, also printed in 1978, Tuvek narrates for us his adventures on this continent and his pursuit of his mother.

Tuvek can't swim and doesn't know how to sail, but luckily a slave he has freed from some of his enemies and now worships Tuvek is an expert guide and sailor, and this guy accompanies our protagonist across the briny deep. A hurricane strikes, and after he and his buddy are nearly killed Tuvek stretches his psychic muscles, first doing a little weather engineering and ending the hurricane and then walking on water--he even gives his comrade the ability to stride across the waves with him. Able to heal or kill people instantly, and to hypnotize them into doing his will, Tuvek has no trouble taking over a merchant ship captained by a pederast and crewed by galley slaves and their brutal overseers.

The first third or half of Quest for the White Witch has a more jocular tone than did the preceding novels. For example, Tuvek uses his miraculous powers to play what amount to practical jokes, like hypnotizing slave overseers into lashing themselves--in the face!--with their iron-toothed whips. And his powers are so great we can't expect anything conventionally bad to happen to him; he can knock out a dozen soldiers in an instant with a thought, and heal any of his comrades who get injured. Fortunately, things turn grim and gross further into the narrative and the later sections are full of the tragedy and suffering we are looking for--sure, Tuvek can't be killed, but he can suffer alright!Tuvek's newly acquired ship and its crew, now his worshipers, carry him to the vessel's home port, a bustling city on that southern continent. There is no intercourse between this continent and that of Tuvek's birth, and the people here have never heard of Vazkor or Karrakaz (or so it seems.) Tuvek takes up lodgings in a brothel that caters to male homosexuals, a favorite haunt of his ship's captain, and makes himself the talk of the town under the name of Vazkor by performing such PR stunts as healing scores of mendicants in a city park, hoping to draw the attention of and smoke out his mother.

Like 180 pages of this 300-page novel take place in this town, and Lee tells us all about the city's history, geography, social and ethnic demographics, and so on. Tuvek gets involved in court intrigues, a duel, and sexual trysts, and he makes friends and enemies among all levels of society; significantly, a subaltern ethnic group hopes he is their god of darkness, come to restore the glory of their empire and punish the more advanced ethnic group that conquered them a century ago and now rules the city, relegating them to membership in a slave and servant class with restricted rights (they can't own blades, for example.) He uses his powers to heal many people, and to kill people, and Lee spends a considerable portion of her text on Tuvek's conflicting and ambiguous feelings about his power and the role he is playing in the city; like his parents he is essentially cold and callous, and finds healing masses of poor people to be irritating work. Tuvek doesn't heal the wealthy for free, either, but instead charges them high prices to make the money he thinks he needs to track down his quarry. His investigators fan out through the city, looking for clues as to the whereabouts of the white witch who birthed and abandoned him.

In the middle third of the novel Tuvek, with total disregard for human life, manipulates the opposing factions within the city and engineers an uprising by those primitive colonized darkness-worshipers; he then helps the faction of the aristocracy he favors to crush this rebellion and seize power from the tired and obese old pederast sitting in the throne. (The faction Tuvek champions is led by a young vigorous homosexual who has a crush on Tuvek.) This campaign features disguises, secret passages, and Tuvek's first use of his powers to actually fly, something that was foreshadowed back in The Birthgrave. Thousands of people lose their lives and important parts of the city, like the port, are wrecked; those natives who have been under the heel of the colonizers for a century are almost wiped out, even those who were not rebellious being killed by the fearful majority during the crisis.The marginalized autochthons achieve their revenge, however. One title held by their god of darkness is "Shepherd of Swarms," and in some pretty disgusting scenes the city is struck by a plague of flies so thick hundreds of people die when the insects enter their mouths and nostrils and choke off their breath! Many people who survive the plague of flies then die of the diseases the flies have brought! Tuvek doesn't use his psychic powers to battle the plagues because he finds that the mysterious enemy behind the pestilence feeds off any sorcerous energy he radiates! Is this plague the work of the god of darkness, or some other magician concealing him- or herself behind that image--could it be Karrakaz herself preemptively seeking to destroy Tuvek? (The revelation of who is behind the plagues is a well-plotted and very effective little twist.)

The city section of Quest for the White Witch ends with yet another good horror sequence, as Tuvek appears to die of the plague, and then rises from his grave, he being practically invulnerable, after all. He finds along with him in his tomb his lover, the bisexual mother of that gay prince; she committed suicide after her son's death from plague and the taking of the throne by his rival. Tuvek tries to raise her from the dead, but her soul has left for another plane, and he only succeeds in animating her soulless body, which acts in a violent, unhinged manner.

As his father did before him, Vazkor son of Vazkor has devastated a city and a society in the failed pursuit of his own selfish goals, and like his mother before him he has been the cause of suffering and death to all his friends and lovers. Suddenly, a new clue comes to his attention, and he heads out of the ravaged city to continue his quest, though his recent experiences have sobered him and he does not feel the hate for Karrakaz he felt when first he made his vow to slay her.There is also plenty of stuff in Quest for the White Witch for all you gender studies types. The people of the southern continent call ships "he," not "she" as we typically do (or did; maybe we aren't supposed to do that anymore.) Sex between men and boys is common in the city, and the city is home to a multitude of pretty boys who dress as women--it is suggested that all this pederasty and transvestism is partly a byproduct of the fact that women of the subordinated race are rarely allowed to leave home and when they do venture out they must conceal their bodies and faces. It is also noteworthy that, while our protagonist is a heterosexual man, the plot is driven mostly by the women and gay men he interacts with, his actions being a response to them and how they make him feel. Whether Lee portrays women and homosexuals in a positive, sympathetic, or realistic light I will leave for individual readers to judge; suffice to say Lee presents all her characters and themes in a way that is ambiguous and challenging. Lee's depictions of colonizing and colonized populations offer another example: neither the ruling ethnicity nor the subjugated are presented in a particularly sympathetic light. Lee doesn't seem to see it as her job to teach us how to think or how to live, but to shock, disturb and entertain us, and because she is a master at all the traditional nuts and bolts of writing--pacing, tone, painting images, etc.--and has no qualms about dealing with material both outré and horrible, she succeeds admirably in her aims.

Thumbs up for Quest for the White Witch and all the Karrakaz books, all of which appear to be widely available; note that some recent editions of Quest for the White Witch have been printed under the title Hunting the White Witch, and that the edition I own, UJ1357, has many annoying typos.

Friday, July 9, 2021

Weird Tales Project: 1932

Our time here on this Earth is brief, my friend. So maybe you should think about doing something worthwhile during your short stay on this big blue marble. Take me, for example. I have dedicated my precious time to trying to read at least one story from each issue of Weird Tales published in the 1930s, and then bending my grey matter to figuring out whether and why one story about a scientist or wizard from Atlantis, or a tough guy fighting an ape or a witch doctor, or an archaeologist getting eaten is better than another one. A fulfilling life is one with a purpose, my friend, that is my advice to you.

My manifest destiny continues to unfold--I have now read and blogged about at least one story in each issue of Weird Tales dated 1932! Below find the list of these stories complete with links to my blog posts about them.

(If I go for extra credit and blog about any further stories printed in a 1932 issue of Weird Tales I will add them to this list with a parenthetical note.)

Below I'll put links to the blogposts with lists for the other nine years covered in this ambitious literary project of mine--gotta catch 'em all!

1930 1931 ---- 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939

February

Vazkor, Son of Vazkor by Tanith Lee

"Whoever and whatever he is, he shall suffer." His eyes returned to me. "Do you comprehend?"

"I comprehend that in Eshkorek the women are vipers, and the men dogs walking on their hind limbs."

In Tanith Lee's 1975 novel The Birthgrave, Karrakaz, the sole survivor of an ancient lost race of almost indestructible psykers, was impregnated by Vazkor, the human wizard and conqueror whom she both loved and hated. Karrakaz switched her and Vazkor's super strong baby with the almost dead baby of brutish barbarian chief Ettook and his beautiful wife Tathra, and 1978's Vazkor, Son of Vazkor, is a memoir written by this super-powered changeling. Vazkor, Son of Vazkor, is like 210 pages of text in my copy (DAW No. 272, UJ1350), split into two books, Book One relating the narrator's youth among the barbarians who raised him, Book Two his adventures after leaving the tribe as a captive of the sophisticated inhabitants of a city ravaged by the wars caused by his ambitious father.

Karrakaz and Vazkor were not particularly sympathetic characters, and so their son, called Tuvek among the barbarians, is just following in their footsteps when on the third page of this novel he rapes a fellow teenager--but hey, she was leading him on! Tuvek is not popular with the other kids because lovely Tathra is resented by all the other women of the tribe, the subject of their envy and jealousy as an outsider whom piggish Ettook captured on a raid. It doesn't help that Tuvek is better at everything than everybody else--shooting a bow, throwing a spear, wrestling, etc.--and that his super body never scars--the fact that he can't wear the ritual scars and tattoos borne by all tribal warriors marks him as an outsider even more than his foreign looks. Tuvek also has an Oedipal thing going, doting on the beautiful woman he thinks his mother and detesting his fat ugly "father."

Tuvek, by age fifteen, is the best warrior in the tribe and has killed many enemies in the raids and battles that are so common among these nomadic tribes; by age nineteen he has killed more men than he can remember and has three wives and a dozen sons. (Lee demonstrates the low esteem in which women are held among the tribes by having Tuvek not even keep track of how many daughters he has sired on his wives and the numerous other willing and unwilling recipients of his seed.) A party of slave raiders from the city of Eshkorek carries off some men from the tribe--the raid is irresistible because it is preceded by a surprise artillery barrage, which leaves the barbarian tribesmen, who have no experience with gunpowder weapons, in shock and awe.

|

| Some editions of Vazkor, Son of Vazkor, bear the title Shadowfire |

Only Tuvek is brave enough to pursue the slavers. Among the slavers are former soldiers of Vazkor's armies, and Tuvek so resembles Vazkor they think their former master has risen from the grave and are stunned, making them easy prey for Tuvek and the slaves he liberates. Tuvek rapes a gorgeous city woman he finds in the slavers' camp and brings her to the tribe as his slave. This woman, Demizdor, has contempt for the barbarian Tuvek and his people's primitive culture, but she can't help but fall in love with him; similarly, Tuvek, who has always treated women like possessions on the same level as his dogs and horses, finds himself feeling tenderly about the haughty Demizdor, even craving her approval and consent! These two crazy kids try to stifle their feelings, but eventually succumb and get married, causing some upheaval in the tribe, who have it in for the beautiful outsider, Demizdor, just as they do for Tathra and Tuvek.

At the close of Book One many pivotal events happen at once and set the plot on a new course. Tathra dies in childbirth, and the midwife reveals to Tuvek that Tathra and Ettook were not his blood parents, that he is the son of a strange woman who referred to her mate as Vazkor, the name of that warmongering tyrant Demizdor was telling him about. Tuvek immediately conceives a hatred for his biological mother for abandoning him and because she killed his father. His antipathy for Ettook is enflamed into a murderous rage because Tathra died trying to fulfill the chief's selfish demand for another son. The realization his real father was a wizard triggers some of the powers he has inherited, and Tuvek uses them to kill Ettook; this first use of his psychic abilities exhausts him, and the tribesmen tie him up and gang rape Demizdor. Tuvek and Demizdor are saved from a painful execution when, months after Tuvek seized her, a cavalry company from Eshkorek finally arrives to rescue Demizdor and capture Tuvek. The people of Eshtorek abominate the memory of Vazkor for starting the wars that wrecked their city, and are eager to take out their bitterness on Vazkor's purported son. A still unkinder cut is that Demizdor, back among her city slicker countrymen, now also hates Tuvek, he having dragged her from sophisticated city life into the nightmare community of Ettook's tribe of barbaric rapists.(Lee is not afraid to portray women as embodiments of all the age-old stereotypes men hold of women, a pack of petty, fickle, vain, jealous, envious, and phony backstabbing bitches, and a big theme of these Karrakaz books is how we resent the power over us held by those we love or desire and how our disappointment when they fail to live up to our hopes can turn our love to hate.)

In Book Two we find that the people of the half-ruined city of Eshkorek are split into three competing factions. The leader of one such faction kidnaps Tuvek, saving him from torture and death at the hands of the other two. Tuvek becomes this guy's cossetted slave, a sort of pet given the job of breaking horses and held in reserve as a sort of super weapon. Tuvek's service is rewarded with fine food and plenty of women. There is palace intrigue, in which people, including Demizdor, try to murder Tuvek. When Demizdor's elaborate plan to get Tuvek killed by a crazed horse succeeds only in getting him sentenced to execution, Demizor's love suddenly overcomes her hate ("You are my life," are her last words to him) and she guides Tuvek to a tunnel through which he can escape the city before she commits suicide. (A lot of people commit suicide in this book.)

The miles-long and elaborately carved and mosaiced tunnel is the centuries-old work of Karrakaz's people (well, the work of their slaves at their direction, I guess.) Fighting men from Eshkorek, some of Demizdor's relatives and admirers among them, pursue Tuvek through the tunnel and out the other end, and there are chases and woodcraft and ambushes and all that sort of business. In the last quarter of the book, Tuvek meets the same generous tribe of vegetarians his mother met at the end of The Birthgrave, and they guide him to a secret island just off the coast. There a young tribeswoman, a healer and mystic, helps Tuvek learn about his psychic powers and, perhaps thinking this is a Theodore Sturgeon story, argues against the incest taboo. When Tuvek's pursuers catch up to him and in the ensuing fracas fell the woman, Tuvek is able to heal her mortal wound. But the story doesn't quite end on this redemptive note: Tuvek swears a solemn oath to the shade of his father that he will kill his mother and following a clue sets sail for a lost continent on his mission of matricide.

Vazkor, Son of Vazkor has many of the remarkable elements of The Birthgrave--rape, bestiality, incest, suicide, spouses who hate each other, parents who hate their children and vice versa, slavery--but it is somewhat less striking and compelling. There are fewer monsters and less magic and mystery and surprise, for one thing. The story is also less tragic and grim; one of its themes is Tuvek growing as a person and learning to treat women better, and many of the scenes with the kindly tribe of vegetarians at the end are actually sweet and cute, though the prominence of incest in these passages will sour them for some readers.

(My copy of Vazkor, Son of Vazkor also has lots of annoying typos, which I found distracting. Hopefully this was remedied in later editions.)

While not as impressive as its predecessor, I still enjoyed Vazkor, Son of Vazkor and feel no hesitation about reading the final installment of this epic, Quest for the White Witch, and finding out how the saga of Karrakaz and Vazkor and their son finally shakes out.

Wednesday, July 7, 2021

June-July Rereads of Barry Malzberg and Tanith Lee

Inspired by that two-hour interview of Malzberg, I reread The Day of the Burning, which I first read in 2011; feel free to check out the 2017 blog post into which I cut and pasted my 2011 Amazon review of the 1974 novel. The Day of the Burning is a fun--but bleak!--satire of the public welfare system and the inability of government--portrayed as hopelessly corrupt and incompetent--to help poor people, or really accomplish much of anything, as exemplified by subplots about failed space missions to Mars and Venus and terrible urban unrest. Sexual dysfunction also figures in this one, as in so many of Malzberg's productions, and there is a sort of sub rosa attack on Christianity; also presented is the idea that there is an unbridgeable gulf between the educated middle classes and the uneducated working and lower classes--interestingly, in this novel the representatives of the middle classes are hapless and impotent, while the lower orders are vigorous, aggressive, even perspicacious, but still doomed.

Malzberg has addressed sexual failure and the shortcomings of the welfare system and the space program time and time again in his large and somewhat repetitious oeuvre. One thing that sets The Day of the Burning apart is a sort of solipsistic brand of literary criticism, in which Malzberg has characters (who may or may not be figments of the probably insane narrator's imagination) attack the narrator's writing--each element of the narrator's prose which his readers dislike is an element characteristic of Malzberg's own style.

**********

Way back in 2010 I read Tanith Lee's breakout novel, The Birthgrave. (In 2013 I copied my three-year-old Amazon review of the novel into this blog.) In 2010 I owned the 1982 DAW edition with the Ken Kelly cover and the Marion Zimmer Bradley intro. I guess I sold or lost that book in one of my many moves, so when I recently had the idea of reading it again in preparation for reading its sequels, I bought a 1975 edition with a George Barr cover that advertises the Bradley intro but, due to some strange mishap, does not include it. (I really should have held on to that 1982 printing.)A woman awakes underground--she doesn't remember any specific thing about herself and little about her origin or milieu. A voice tells her she is the sole surviving member of a fallen race of arrogant and evil men and women far superior to mere humans, and that she is cursed and will not find happiness. The volcano above her begins to erupt, and she flees. She doesn't know her own name and she is afraid to see or show her face, and she travels the world, always wearing a mask or veil, on every hand finding the physical artifacts and cultural remnants of her own long lost race of cruel overlords and enduring dreadful adventures that last 400 pages of fine print!

This book is long and dense, but it is a pretty smooth read. Lee's prose is good, with lots of vivid descriptions and clever or powerful metaphors, and on almost every page we find disturbing sex or grotesque violence, a classic SF or sword and sorcery concept (e.g., ruined haunted cities, chariot races between archers, castles full of secret passages and moats inhabited by voracious monsters) or some allusive clue about this strange woman or her world. Because of her striking appearance and miraculous powers (these powers sometimes recall the abilities of a vampire, sometimes the miracles of Jesus Christ), everywhere she goes the narrator is the center of attention, received as a goddess or a witch or a hero, sometimes exciting abuse and resentment, often admiration and worship. All you grad students may be excited by the novel's many innumerable references to gender and sex roles; Lee depicts many societies in The Birthgrave, and they all have different ideas about how women should be treated and what a woman's responsibilities are, and as a weird outsider with special powers the narrator can inhabit any of these roles and can slip through or batter down any of their restrictions.

Even though The Birthgrave is about a beautiful woman who is better than everybody else and has as one of its main topics the place of woman in society it doesn't come off as a wish fulfilment fantasy or some kind of feminist polemic. This novel is grim. Everywhere the narrator goes calamities and tragedies abound, suffered by those who seek her help or strive to aid her as well as her enemies and scores of innocent bystanders. The sex and violence in the novel is rough and nasty rather than life-affirming or glorious; success in love or battle, when it does come, does not lead to peace or joy. The narrator is compelling but not really sympathetic--she is cold, callous, and alienated, and buffeted by the winds of fate hither and thither she commits all kinds of crimes offhandedly, and experiences indignities and reversals as well as triumphs; none of the triumphs really profit her or anybody else.

Halfway through the novel, after dealing with bandits and villagers and fighting in the hippodrome, the narrator meets a man with powers much like hers--the general Vazkor. She has a love-hate--mostly hate--relationship with Vazkor, who uses her as a tool in his pursuit of his doomed Napoleonic dreams of taking over a kingdom and then uniting all the other kingdoms under his rule through chicanery and total war. There is plenty of backstabbing and palace intrigue, and a weird love triangle, as well as long marches and sieges and ambushes and all that. The narrator is impregnated by Vazkor, and her efforts to abort the baby come to naught, as the baby has inherited her super-durability.

Her final showdown with Vazkor drains much of her power and in the final quarter of the novel the narrator finds herself a slave among a cruel barbaric tribe, the body servant of the chief's beautiful wife. This woman and the narrator give birth the same evening, and the narrator switches the babies, replacing the chief's wife's own sickly baby with her own super baby. The narrator then sneaks off, joins another, more welcoming tribe, and then we arrive at The Birthgrave's crazy finale. Threatened by a lizard bigger than an elephant, the protagonist and the kind tribesmen are rescued by a flying saucer which kills the lizard with a ray cannon. The narrator goes to the saucer and joins the spacemen, who tell her she, unconsciously, summoned the saucer to herself with her psychic powers--her mental abilities allow her to control the ship's computer. This computer is able to read her mind and unlock all her lost memories and cure her psychological problems: she and we learn the truth of the fall of her superior race, how she was interred under that volcano and survived so long, what her face looks like, and the psychological and psychic reasons for all the wild stuff that has been happening to her. The spacemen then leave and the narrator, who now knows her name, apparently starts living life as a hermit.I enjoyed The Birthgrave but some will dislike its despairing tone and some may find the Freudian science-fiction ending jarring or disappointing (though it is all foreshadowed.) I'm curious to see what happens in the sequel, Vazkor, Son of Vazkor, whose 200-plus pages I will be discussing in the next episode of MPorcius Fiction Log.

Weird Tales Project: 1931

Like Aeneas, I am a man apart, devoted to my mission. That lofty mission: to blog about at least one story from each issue of Weird Tales printed in the 1930s. And just as Rome was not built in a day, reading over 100 stories about guys exploring tombs and never returning from them, vampires, mighty-thewed barbarians and astronauts who get killed takes a little time. But I am making progress in this odyssey, and today I bring you proof! A list of all nine issues of Weird Tales published in 1931 and the stories I have read from each, with links to my musings about each.

(Should I blog about any additional stories printed in a 1931 issue of Weird Tales--it could happen!-- I will add them to this list with a parenthetical note.)

Here you'll find links to the other nine blogposts that will together form my official after-action report about this arduous campaign:

1930 ---- 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939

January

February-March

April-May

June-July

August

September

Clark Ashton Smith: "The Immeasurable Horror"

October