To me, the biggest name in

Alternities is Barry Malzberg. (Ed Bryant was also a draw.) But by an objective measure, like sales, Greg Bear and Vonda McIntyre are probably bigger names to the SF world at large than our pal Barry. Can either Bear or McIntyre produce a story that will prove 1974's

Alternities is something more than a collection of odd trivialities and childish dick jokes that is perfectly calibrated to offend prudes, feminists and the LGBT crowd?

"Webster" by Greg Bear

I haven't read anything by prolific author Bear, but today that Bearless period ends, as we examine "Webster." "Webster" was never picked up by any other anthologies, but it was included in several collections of Bear's work.

Bear immediately tries to get me on his side by mentioning Roy Chapman Andrews in the first paragraph of this story. One of my very first book-related memories is of reading

In the Days of the Dinosaurs with Nana, my maternal grandmother. This story actually has little if anything to do with Andrews or dinosaurs, though the reference to Andrews' pioneering discovery of dinosaur eggs does foreshadow a strange birth and discovery in the story.

Regina Abigail Costes is a fifty-year-old virgin living in a small apartment, lonely and horny, her only companions her books, most prominent of which are a Bible and a dictionary. She dreams of having a man, and hits upon the idea of magically conjuring forth a man from the dictionary! Tall and handsome, the man, whom she names Webster (

"Johnson" would have been funnier, but maybe wouldn't work in the story's 20th-century American context) has sex with "Abbie." The next morning she bursts out onto the street and says "I

know...what all you other women know." The clouds and the sky tell her "Breathe deeply. You're part of the world now. The real world." (Bear really goes in for this sort of overwritten romanticism.) Apparently Abbie (and maybe even Bear?) hasn't heard that a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle and thinks a woman is not complete without a sexual relationship with a man.

Webster can't go outside, doesn't eat, and he and Abbie have nothing to talk about. Their relationship pales after a few weeks, Abbie even buying a gun, wondering if Webster would survive being shot. For his part, Webster acquires a dictionary of his own, likely to create a woman with whom he has something in common. In the end of the story, more or less by mutual consent, Webster is dispelled and Abbie heads to the bookstore, I guess to get a different book to conjure a different man? The last line of the story is "She had her choice now." This ending is a bit confusing to me; didn't she just learn that love with a golem or simulacrum or whatever word we want to use was impossible, that such relationships are unsatisfying? Let's be optimistic and believe she is going to the bookstore to try to date up one of the customers or clerks, not get material needed to conjure up Mr. Darcy or Heathcliff or Odysseus.

I think the plot and themes here are good, but Bear's style, especially at the start of the story, is long winded, overwrought, and heavy-handed. Still, I'll judge this one marginally recommendable.

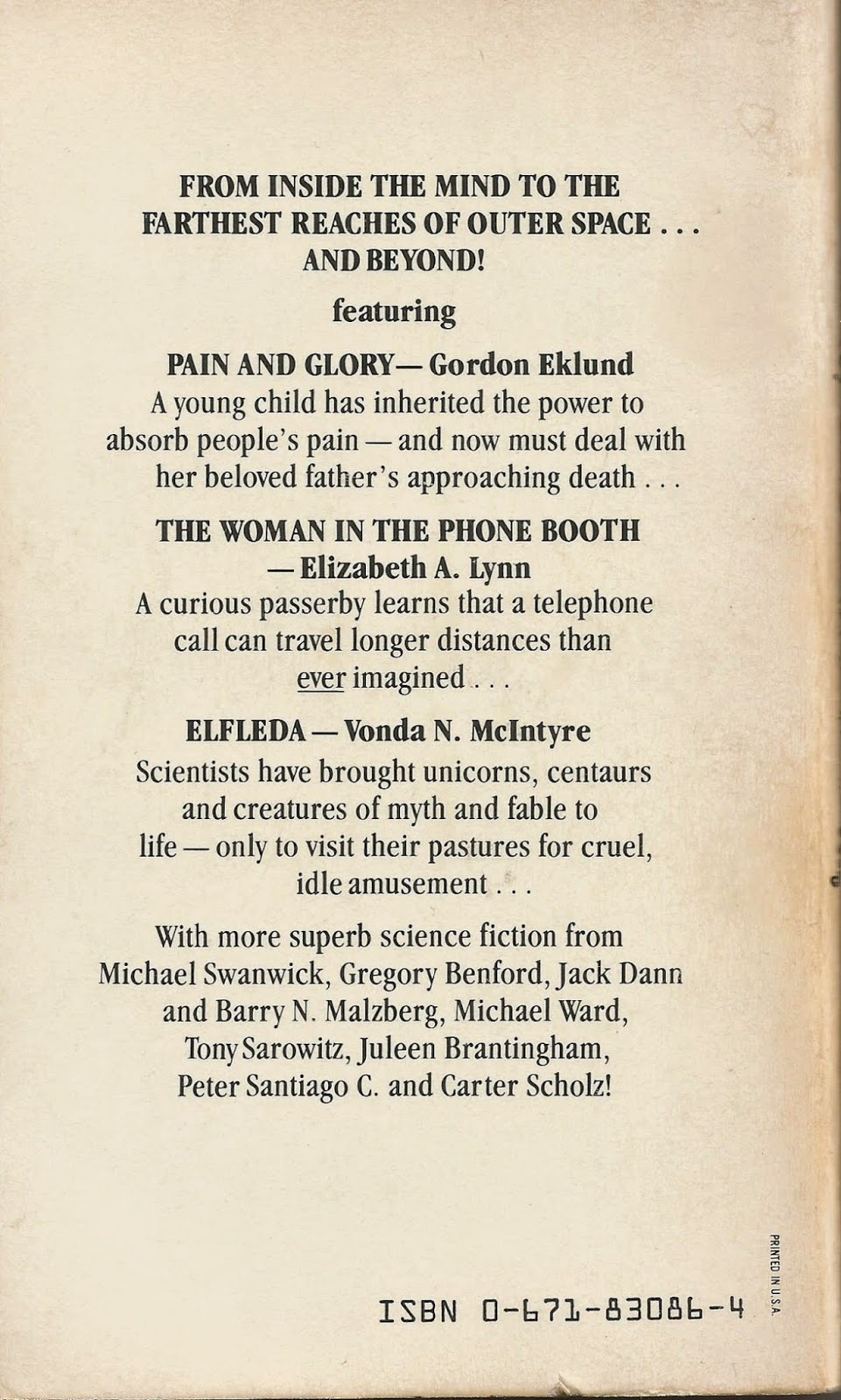

"Recourse, Inc." by Vonda N. McIntyre

In 2014

I read McIntyre's "Only at Night" and thought it quite good, and "Elfleda" and

thought it just OK. Let's see what we make of this one, which would reappear in the 1979 collection,

Fireflood and Other Stories.

"Recourse, Inc." tells a story with a series of documents, first an advertisement, then a bunch of letters and telegrams. A man with psychological problems was told by his therapist to start using credit cards in order to gain confidence(!) One of the banks whose card he has is overcharging him, either due to computer error or criminal intent, sending threatening collection letters for huge amounts. Recourse, Inc. is a sort of

A-Team of people on the edge of the law (former green terrorists, it is implied) that comes to the aid of those harried by collection agencies and fraudulent businesses. Through correspondence we follow their efforts to get the disturbed man restitution and punish the bank; they try legal means, contacting the government (North America in the story's setting appears to consist of numerous largely autonomous states under a relatively weak federal government), computer hacking (is this 1974 reference a pioneering depiction of attacking a computer over the phone lines?), and eventually resort to breaking and entering.

One of the story's themes, I think, is the idea that late-20th-century (North) American society, which seems so stable compared to societies of the past and of other regions of the world, is in fact resting on a shaky foundation. If the computers all go kablooey, or all the oil is suddenly eaten by bacteria--and in this story such things seem very possible--we are in serious trouble! In the world of "Resource, Inc." governments and other people and institutions with authority or power, including scientists, psychologists, and businesses, are incompetent and/or untrustworthy.

I don't like the plot any more than the plot of Bear's story, but McIntyre's execution is much better; the story is economical, with each sentence adding to the story, each sentence in the voice of a character. There is no fat, no fluff. "Recourse, Inc." is a strong contender for the title of "Best Story in

Alternities."

"The Legend of Lonnie and the Seven-Ten Split" by E. Michael Blake

True story: Once the academic department where I worked in Manhattan took some of the public monies (meant to finance public policy research) with which we were entrusted and used them to go bowling. This is called "a team-building exercise." None of us was a regular bowler, and so, by employing the tactic of violently hurling the ball down the lane with all the strength I could muster, I won the title of best bowler in our office of depressed slackers, arrogant hipsters, and committed bolshevists.

Blake has 11 fiction credits at ISFDB and a brief look at his

livejournal page suggests his SF-related work is meant to be funny and includes cartoons and skits.

Twenty-year-old Lonnie is the best bowler in the overcrowded America of the future, where almost every square mile is covered in "Urban Complexes." Except for the five kilometers around Las Vegas (known as "LaVe"), a city of sinful pleasure operated by the "Satan-Mephistopheles-Diablo Holding Company." Most who enter LaVe do not return, but those who do escape become legends, and Lonnie seeks to become just such a legend.

This is one of many stories about making a deal with the Devil and/or competing with the Devil, like in that 1979 song,

"The Devil Went Down to Georgia." Instead of competing in a violin competition, Lonnie bowls against the Devil. Lonnie is an expert practical physicist (Blake edited

Nuclear News and includes lots of references and jokes about such topics as probability curves, electrons, and Karl Schwartzchild), able to bowl a strike without fail after learning the nooks and crannies of an alley. Lonnie wins his bet with the Devil, and is even clever enough to escape the city when the Devil tries to badger him into joining up with Satan-Mephistopheles-Diablo Holding Company; the SMD offers high salaries and easy women, but Lonnie has seen how working at such a firm can destroy a man's body and soul.

This story actually fits the old fashioned SF model of a guy succeeding because he is clever and cunning and knows all kinds of hard science and engineering jazz. It also fits right in in

Alternities with its juvenile sex joke--the guy who runs the bowling alley in LaVe bears a curse which limits his sexual activities to intercourse with the finger holes of bowling balls, and poor Lonnie has to witness just such a performance.

Mildly entertaining. Blake has no collections listed at isfdb, and "The Legend of Lonnie and the Seven-Ten Split" never appeared elsewhere, though personally I think it would be quite suitable for an anthology of 20th-century stories about the Devil, or of SF/F stories about sports. I assume there must have there been such anthologies.

"Sign at the End of the Universe" by Duane Ackerson

Anything I write about this story will be longer than the story itself:

Maybe this story is about how arbitrary our points of reference and points of view are. Or maybe the point of the story is that our world, so full of crime and war and heartbreak, is the exact opposite of what it should be.

A silly and gimmicky piece, but if we choose to judge the stories in

Alternities on an efficiency basis, this one isn't bad. Ackerson has only six fiction credits at isfdb, but many poetry credits.

"No Room for the Wanderer" by Lee Saye

Saye has four stories listed at isfdb.

I like art, and I like fiction, and I like poetry, but the self-importance and pretension of some creative people can really make me roll my eyes. "Art is work" and "Art is not a luxury" and that sort of thing. As if life for smart educated people wasn't already easy enough in our welfare state society in which the taxpayers are subsidizing the library, the museum, the opera, the university, et al, creative types turn around and tell the farmers, truck drivers, mechanics, electricians, plumbers and police officers that keep our society from collapsing into starvation and mass violence that those productive types couldn't survive without the artistes' daubs and scribbles--the parasite mistaking itself for the host!

Saye's story is about a poet with a degree in English literature who seeks to volunteer for a place on a starship headed for a new colony on an alien planet. When he is told that the colony is only accepting people with technical or scientific skills, or tourists who can pay their own way ("We're starting a whole new civilization out there and we need mechanics and engineers. I'm sorry."), the poet says "You're building a whole new civilization with technology, but there's no room for the poet. I'm sorry for your civilization." This jackass looks down on any civilization that lacks his own divine presence!

Besides the obvious fact that it makes sense for pioneers in a hostile wilderness to have technical skills and not waste resources shipping an unproductive person across a bazillion miles of space, it is ridiculous to think that people with technical training cannot create a vibrant and satisfying artistic and literary culture. Lots of artists and writers, particularly in the SF field, have had science or engineering degrees, and/or held real 9 to 5 jobs.

I'm not sure if the protagonist of "No Room for the Wanderer" is expressing the author's own view, or if we are supposed to think the poet is being absurd. Either way, this story is well-written and thought provoking, and I'm giving it a passing grade.

***********

It is with some surprise that I report that all five of these stories from Alternities are worthwhile. Our first two expeditions among its pages were a bit rocky, but today's tales raise the average of the volume to an acceptable level. Gerrold and Goldin didn't sell us a pig in a poke after all.