In our last episode we read three stories in 1950s SF magazines by Evelyn Goldstein that were about traditional SF stuff (post-apocalyptic life, robots, genetic science) but also about parenthood in bizarre or difficult circumstances. I thought all those stories had merit, so let's read four stories from the tail end of Goldstein's brief career as a SF writer. Just like the three from last time, today's four stories are available for free at the internet archive.

"Man's Castle" (1959)

This is a gimmicky sort of twist ending story, brief and sort of shallow. A married couple, Arnby and Marilee, live in a village, and through their conversation we learn that the wife spends her time carving the work of important poets into stone; she has just finished up Whitman's Leaves of Grass (carving it in in espanol and francais as well as English) and is going to start on A. E. Housman. We also learn that her husband has just been elected king. I thought this was going to be one of those SF stories about how in the future there is no work so people have elaborate hobbies. But then came a strange passage which suggested that, during a period of government mandated "trial matings," Arnby and Marilee each had sexual relationships with other people. Finally, at the end of the story, we learn that Arnby and Marilee are among the last hundred or so people left alive on Earth, that a nuclear war sixty years ago when A and M were kids killed almost everybody and left any survivors sterile. The trial matings, twenty or so years ago, were a vain attempt to find a fertile couple, and all that carving Marilee does a quixotic effort to preserve the height of Earth culture for eternity.

Acceptable but weak. "Man's Castle" was published in Fantastic Universe, alongside stories by Harry Harrison and Harlan Ellison.

"Man Under Glass" (1959)

Thirty-seven-year-old Craig lives in a domed city, a futuristic metropolis with moving sidewalks where what jobs people work and what clothes they wear and who they marry and how many kids they have is carefully controlled by government. Tonight is Carnival, an annual celebration, and everybody wears strange costumes and dances in public and throws confetti about--the government head shrinkers think the citizens of this conformist society need one night a year to act wild, getting drunk and having promiscuous sex, to "let off steam." But Craig is not losing himself in the party atmosphere; he wears an old military uniform, one to which the revelers respond with unease. In a series of flashbacks and exposition as we follow Craig's Carnival experience--he encounters a pretty girl who on this festival night is performing as a fortune teller and then a mutant apeman--we learn the history of Craig's future world and his own place in it.

Craig is out of step with his time, an expert on the past and an aficionado of the old ways who works as an archivist. Over two centuries ago the world was wrecked by an atomic war. Old nations collapsed and new ones were built under domes, and the public and government revolted against science and the military; mobs lynched service men and many types of scientific research were legally forbidden. Craig's grandfather was a high ranking military aviator and one of the victims of the mob--the uniform Craig wears is his grandfather's, an heirloom hidden from the authorities. (People in this story live to be 150 years old, so don't worry your head that there is some oddity about Craig's grandpa being a young man 200 years ago.)

When Craig was a kid it was determined that the air outside the dome was finally safe to breathe, and the dome doors were unlocked, but (as we see in a flashback to Craig's experience on that day) nobody was brave enough to go outside! The whole human race has agoraphobia! To this day, though it is not illegal to go outside, there is a powerful social taboo on leaving the dome, and nobody has done it--except our man Craig!

Infertility brought on by nuclear war is a theme in three of the Goldstein stories we have read already, and so it is here in "Man Under Glass"--the number of new births is dwindling, threatening the human race with extinction. In Craig's youth, scientists developed an artificial means to create people, but almost all the people they were able to brew up in their labs (the "Laborn") were hideous mutants, freaks with wings or lacking limbs or with nebulous blob bodies or whatever. The common people formed mobs to lynch all these monsters (lynch mobs are a recurring motif of this 30-page tale and we see them in action in another flashback to Craig's incident-rich childhood) but some have survived--on this Carnival night Craig meets two, the aforementioned fortune teller (her mutations are not visible to the naked eye) and apeman. Craig tries to help the apeman when a mob and the cops come after him, but the simian sport can just teleport to safety and it is poor Craig who is captured by the police.

Goldstein's plot moves at a rapid pace after Craig finds himself in custody, and we readers and our hero are confronted with a whirlwind of developments and twists. Craig is interrogated by Bordon, the "Chief of Mental Security," who then enlists him to marry his daughter Ann--that beautiful fortuneteller! One of the lab grown mutants, Ann a psychic who is expected to enjoy a 1000-year lifespan and has been living incognito as Bordon's daughter. Ann is also a virgin who has been exempted from the government-mandated premarital sex exercises, and when Craig climbs into bed with her to consummate their marriage the psyker teleports away!

Craig is the only normal human able to leave the dome so he is sent out to find Ann and the other lab grown mutants; fortunately they are not shy about revealing themselves to him. Ann and a similarly gorgeous Laborn man, Everett, tell Craig that they are homo superior, and will be the Adam and Eve of the new human race--it looks like Craig's marriage with Ann is off! And there is more bad news coming! Ann and Everett (and even sterile mutants like that apeman) can teleport to other planets and communicate with various alien races. It turns out that all the aliens are gentle and pacific, just like homo superior, and they don't want violent and aggressive homo sapiens screwing up their peaceful galaxy; Ann and Everett have decided to accommodate them and keep the peace by euthanizing the lot of us! Fortunately Craig, by pointing out some of mankind's achievements that show an inclination towards peace (like the writings of Confucius and the Magna Carta), convinces the mutants to issue a stay of execution. Then Craig hurries back to the dome, full of plans to work with more flexible and innovative dome citizens like Bordon to reform the human race so we are worthy to shine the shoes of all those peaceful people out there in space and explore the universe.

"Man Under Glass" is not bad, but it is no big deal. Goldstein crams in a multitude of common SF elements, from the domed city, a post apocalyptic world, and artificial people to homo superior, the human race on trial and government control of sex, but doesn't do anything terribly new with them. Maybe the most novel thing is Goldstein's emphasis on puberty and sexual maturity. Bordon theorizes that, because she is going to live 1000 years, that Ann (though she has the body of a thirty-year old) won't achieve sexual maturity psychologically until she is seventy or eighty years old; in the event it is Craig's sexual advances on their wedding night that shock her into full possession of her galaxy-trotting psychic powers.

"Man Under Glass" was published in Fantastic in the same issue as stories by (among others) Fritz Leiber and A. Bertram Chandler.

"Days of Darkness" (1960)

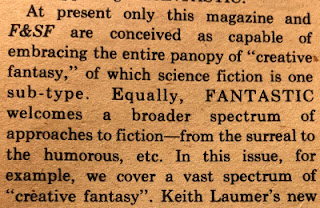

"Days of Darkness" is probably Goldstein's most critically successful story--according to isfdb, it is the only one to ever be republished. It first was printed in Fantastic (in the same issue as the first of Keith Laumer's Retief stories) and then was selected by Jean Marie Stine for inclusion in the 2004 e-book Future Eves: Great Science Fiction About Women by Women, which in 2010 was printed as a trade paperback with a slightly different title and additional content.

"Days of Darkness" may have the approval of the feminist cognoscenti and start off with a Bible verse, but it has a B-movie premise! A flying leech from outer space lands in rural Washington state and begins murdering people living on isolated farms and then entire small towns! The government has its hands full trying to kill this extraterrestrial menace because most of the time it is invisible--human eyes can only detect it when it is in the act of feeding--draining the blood of its victims!

Martha and Zipporah Otumn (dig the Dickensian name!) are elderly women living in a cottage on the last remnants of the Otumn estate--once, before the automobile, the Otumn family were the leaders of the community, their lumber mill its vital economic engine and their mansion its social center. But since then the Otumn family has fallen on hard times--they had to sell the mill and move out of the mansion, it being too expensive for them to heat. Zipporah has been an invalid, bedridden and kept alive by a regimen of pills, for decades. When the state militia comes to evacuate Otumnville to create a free fire zone for the air force to bomb should their new detection scheme pinpoint the space leech there, M and Z refuse to leave! In flashbacks and dialogue we learn all the details of the decay of the Otumn family, which can be traced to M and Z's mother's extreme jealousy, and about how Martha put her own desires aside to serve the interests of the family and look after the ungrateful Zipporah. Back in the present it is not the American war machine that kills the space invader, but Martha--the leech detects its victims by homing in on their selfishness, but selfless Martha is invisible to it! Martha, wielding a cleaver, is able to strike by surprise as it is sucking Zipporah dry and hack the menace from another world to into bite-sized pieces.

"Days of Darkness" is about the response of Earthpeople to invasion by a giant invisible flying leech from outer space, but it is also about women's difficult sexual relationships with men and, more so, women's difficult relationships with each other. Goldstein presents us with two extreme versions of archetypes of female behavior--Zipporah and mother Otumn are jealous, envious, selfish and cruel, while Martha is selfless and giving; the jealousy of the selfish Otumn women leads to their own deaths and the collapse of a successful family, but Martha's self-sacrifice saves the world! I'm tempted to say that Goldstein is putting forward embodiments of how individual women see other women, and how individual women see themselves, but that could just be my own lifelong experience of talking to women coloring my judgement. There is also the possibility that the story is a lament over the shabby way women treat each other, Goldstein taking the line recently espoused in the 2006 book Tripping the Prom Queen. More generally and more directly, Goldstein's story exhorts us to put love of others before love of self--Martha's former boyfriend actually spells this out for us on the tale's last page: "the hopes of mankind lie in its selfless people. Survival will come through the love of one's neighbor over one's self!" Maybe Goldstein wrote "Days of Darkness" with Cold War implications in mind--maybe she thought we should overlook all that business with the Katyn Forest and Berlin Blockade and Hungarian Uprising and just be nice to the commies! (Personally I find the idea that the story is about the dangers of irrational female rivalry over men to be more compelling.)

With its focus on women's relationships and its world-saving heroine, it is easy to see why Stine chose it for Future Eves. And if you can accept the contortions Goldstein goes through to marry the two forms together (uh, we are invisible to the monstah unless we are selfish and it is invisible to us unless it is eating our blood?), it is also a decent alien invasion story and a decent capsule version of a tragic saga of the collapse of an upper-middle class family. I like it.

"The Vandal" (1960)

This is, apparently, Goldstein's last published story. "The Vandal" was boldly announced on the cover of Fear!, a magazine which only ever had two issues, but without the author's name. This is what the kids call a bummer!

In five of the seven stories by Goldstein we have read the author has cast her gaze forward to observe a world ravaged by nuclear war, and in "The Vandal" she does the same; as she does in "Man's Castle" and "The Land Beyond the Flame" she reveals the nuclear was as part of a twist ending.

Abel is an astronaut, the product of a eugenics program and the first man to land on Venus. Abel has a lifespan three or four times that of a normal human being, higher intelligence, and various psychological attributes that are designed to allow him to withstand the pressures of being the only man on Venus. Goldstein narrates how he has explored a desolate cloud-covered wasteland inhabited by only the most primitive organisms as well as a pair of beautiful little Venusioan fairies. If only the human race could learn to live like these little winged people, who love each other and live in harmony with nature and would never ever engage in an atomic war!

One day Abel discovers that the cave where he has been collecting samples and conducting experiments for almost a year has been ransacked. Who on Venus could have done such a thing? Abel searches the grim and inhospitable landscape for the culprit until finally the truth is inescapable--Abel himself vandalized his own research work! Then comes a realization even more horrible--this desolate planet bereft of higher lifeforms is not Venus but Earth! Abel went to Venus, met the fairies, and brought the fairies back to Earth, but found the Earth had been devastated by nuclear war in his absence. His psychological defense mechanisms kicked in, and to keep himself sane he convinced himself that this was Venus, and started collecting specimens of things like amoebas and lichens--the only survivors of the war--and studying them. Periodically Abel realizes the unsupportable reality and smashes everything in a rage, but then his delusion that he is on Venus starts all over again. This cycle of thinking he is on Venus conducting explorations, then realizing with horror he is on Earth, the last of the human race, only to start the cycle anew, has been repeating itself for many years.

Not bad.

**********

These stories, with the possible exception of "Man's Castle," are worth reading for conventional entertainment purposes, but I especially recommend them to those interested in SF by women; "Days of Darkness" in particular is about the lives of women, especially how women deal with each other. On the negative side, in her other stories Goldstein bangs away at the same themes again and again.

I am still enjoying reading all these old SF magazines at the internet archive, and in part because it is convenient (I am away from home and the MPorcius Library) we will continue to explore them in our next installment.

Sunday, December 30, 2018

Saturday, December 22, 2018

Three stories by Evelyn Goldstein

In our last episode we read a story by Evelyn Goldstein in which the main character tortured and murdered innocent people and then was shot down by the cops...on Venus. "God of the Mist" was such a strange (and compared to so many of the other stories in Fantastic Universe's June 1957 issue, compelling) creation that it inspired in me an itch to read further in Goldstein's relatively small body of work. A search through the internet archive's vast collection of old SF magazines turned up most of the nine stories isfdb says Goldstein published, so let's delve deeper into the oeuvre of an SF-writing Brooklyn housewife! Today we'll look at three of Goldstein's tales, all from the mid-1950s.

"The Land Beyond the Flame" (1954)

"The Land Beyond the Flame" appeared in an issue of Planet Stories with an absorbing Kelly Freas cover featuring scaly fish men and a curvaceous human woman. The exciting illustrations continue inside: the first thing we see when we turn to Goldstein's story is a two-page illustration depicting a barren alien landscape where one guy is discharging a ray pistol at hideous monster rats while another actually wrestles the noisome vermin for his life! This is just the kind of thing we are looking for!

There are two kinds of people in the world Goldstein depicts in this story, the Numen, seven-foot-tall men with night vision who live in a high tech city under a dome, and the Olmen, barbarians who live in the wilderness and, as barbarians in stories do, wear loincloths. The Numen dress fashionably but live in a totalitarian society controlled by scientists called Logicians; the Numen have no emotions, their actions are solely based on cold intellectual criteria. The Olmen and Numen do not get along because the Numen, insatiably hungry for biological data, regularly sally forth from their domed city to kidnap Olmen (not to mention Olwomen and Olchildren!) for their vivisection tables!

Allyn is a Numan who's got something wrong with him--he is a throwback who has emotions! So, when the Logicians ordered him to impregnate his twin sister Aleena (cripes!) he refused because the Numen have a genetic defect that results in Numen women dying in childbirth. (The scientific overlords of the Numen wanted Allyn and Aleena to mate in hopes of producing more citizens with a propensity to giving birth to twins.) Allyn fled into the wilderness, pursued by Numen aircraft, and as the story begins he makes friends with an Olman, Keeven, whom he rescues from a pack of giant rats with his flame pistol.

Keeven takes Allyn to his village, only to find that it has been raided by Numen--only Keeven himself and his sister Marva have escaped capture. These three lost souls travel to the Forbidden Area beyond a radiation zone in search of the super weapons rumored to be there (they hope to use said weapons to crack the Numen's dome and rescue Aleena and the captive Olmen.) On the way Allyn and Marva fall in love and our heroes tangle with Numen patrols; like we so often see in adventure fiction, people get captured, people get shackled, people escape, people steal vehicles etc.

In the forbidden land our heroes meet a people who are a hybrid of Numen and Olmen. They have an archive of information about the past, and we learn (despite the illustration which shows three moons in the sky) that this story is set on a post-apocalyptic Earth. The Numen are descendants of people who were mutated by the radiation of the nuclear war, while the Olmen are descendants of people who hid deep underground during the period of the war and escaped exposure to radiation. The Olmen do not suffer the genetic defect that causes death in childbirth, and neither do children of mixed Olman and Numan parentage. Allyn, Keeven and Marva travel to the domed city of the Numen and with the help of the hybrids' psychic powers (the reality behind the rumor of super weapons) persuade the Numen to make peace with the Olmen.

The plot of this story is not bad, but it suffers in the style department and includes mistakes editors should have fixed. "Flaunted" is used in place of "flouted," which is embarrassing. When Allyn kisses Marva for the first time we are told she is "delicious as wild strawberries." How would Allyn know what wild strawberries taste like? On the same page Goldstein tells us the Numen eat only dehydrated foods and she presents a scene in which Allyn is "amazed" by how tasty fresh meat is. Maybe a scene in which he ate fresh fruit for the first time was excised?

Despite its problems, an acceptable entertainment.

"The Recalcitrant" (1954)

The intro to "The Recalcitrant" in Fantastic Universe tells us that "only a woman could have written this story..." that it has "compassion...high poetry...tenderness...[and] the breath of a fierce vitality...." Sure enough, the first paragraph is a bunch of gush about flowers, sunlight, and some chick's dream home!

But not to worry, the rest of the story is not like that. Jim and Alicia are a happily married couple, and over the twenty years of their marriage they have built their farm, house, and beautiful garden with their own hands. But today comes bad news! Jim tells Alicia that "some men" are coming to take him away, and he hides from them in the woods. He is eventually caught, but Jim's performance in the woods (he is very strong and indefatigable, for example) provides us clues that suggest Jim is a robot married to a woman from whom he has kept his true mechanical nature a secret! But when he is brought before the doctors who claim they want to help him, we learn that the truth is even more strange.

Jim is a cyborg, a human brain in a robot body. His body was wracked in a catastrophic war decades ago, a war that reduced the human population of the Earth to a mere half-million! So he could live as normal a life as possible, he was given this robot body, and something else--Alicia, a robot who thinks she is a real woman! But all those robotics were a temporary expedient--the doctors now have developed a real biological body for Jim, with which he can, in a relationship with a real human woman, father human children and help repopulate the ravaged Earth! But Jim is in love with Alicia, even if she is a machine, and resists being separated from his super strong robot body and the wife with whom he has built a happy life! (Alicia is slated to be reprogrammed to work like a drone in a factory!)

This story is pretty good--I was genuinely surprised when it was revealed that Jim was not really a robot and Alicia was. And, while the editor oversells the story, it is certainly noteworthy that both "The Recalcitrant" and "The Land Beyond the Flame" have at their centers obstacles to childbirth and parenthood--maybe Goldstein really does bring a female perspective to the traditional SF template of a melodrama* in which science causes and/or solves problems.

*"Melodrama" is the word Alexei Panshin uses to describe SF stories before the New Wave in his article of criticism in the December 1970 issue of Fantastic; I liked the article and like the word, which is more broad than a word like "adventure" and thus can comfortably encompass a story like "The Recalcitrant."

"Hour of Surprise" (1955)

The blurb on the first page of "Hour of Surprise" mentions motherhood, and I was excited to see the theme of parenthood carrying over from the last two stories. This story appeared in Fantastic Universe, whose editor Leo Margulies (echoing the sentiments he expressed about "The Recalcitrant") tells us it is "tender" and "lyrical."

Aram is a twelve-year-old boy living "Inside" with his two sisters and single brother and their metallic "Mother." His whole world is five rooms, but he knows an "Outside" exists, because Mother sometimes goes out there; when she returns her metal skin is cold, even though she has described "Outside" as a forbiddingly dangerous place of fire.

Mother has also set off limits a room into which she goes while the kids sleep; clever and curious Aram figures out how to gain access to the room and he discovers in there clues that suggest Mother is not their real mother and that they won't grow up to have metal skins themselves! Mother may in fact be a machine who is holding them captive because of some kind of human vs robot war! With the help of his eleven-year-old sister Aram manages to sneak Outside, where he learns the shocking truth (well, shocking to him; I guess it is more or less what we readers expected: the Earth was wrecked in an atomic war and Aram and his siblings, likely the only humans left alive, were left with Mother for safekeeping by their robot-building father.)

I liked it.

*********

I like old-fashioned SF stories, and these are competently executed, and Goldstein's theme of unusual or dangerous parenthood gives them a freshness and an emotional angle that touches our real life experience of having (and maybe even being!) a parent. I enjoyed all three of them and we'll read more Goldstein in our next blog post.

"The Land Beyond the Flame" (1954)

"The Land Beyond the Flame" appeared in an issue of Planet Stories with an absorbing Kelly Freas cover featuring scaly fish men and a curvaceous human woman. The exciting illustrations continue inside: the first thing we see when we turn to Goldstein's story is a two-page illustration depicting a barren alien landscape where one guy is discharging a ray pistol at hideous monster rats while another actually wrestles the noisome vermin for his life! This is just the kind of thing we are looking for!

There are two kinds of people in the world Goldstein depicts in this story, the Numen, seven-foot-tall men with night vision who live in a high tech city under a dome, and the Olmen, barbarians who live in the wilderness and, as barbarians in stories do, wear loincloths. The Numen dress fashionably but live in a totalitarian society controlled by scientists called Logicians; the Numen have no emotions, their actions are solely based on cold intellectual criteria. The Olmen and Numen do not get along because the Numen, insatiably hungry for biological data, regularly sally forth from their domed city to kidnap Olmen (not to mention Olwomen and Olchildren!) for their vivisection tables!

Allyn is a Numan who's got something wrong with him--he is a throwback who has emotions! So, when the Logicians ordered him to impregnate his twin sister Aleena (cripes!) he refused because the Numen have a genetic defect that results in Numen women dying in childbirth. (The scientific overlords of the Numen wanted Allyn and Aleena to mate in hopes of producing more citizens with a propensity to giving birth to twins.) Allyn fled into the wilderness, pursued by Numen aircraft, and as the story begins he makes friends with an Olman, Keeven, whom he rescues from a pack of giant rats with his flame pistol.

Keeven takes Allyn to his village, only to find that it has been raided by Numen--only Keeven himself and his sister Marva have escaped capture. These three lost souls travel to the Forbidden Area beyond a radiation zone in search of the super weapons rumored to be there (they hope to use said weapons to crack the Numen's dome and rescue Aleena and the captive Olmen.) On the way Allyn and Marva fall in love and our heroes tangle with Numen patrols; like we so often see in adventure fiction, people get captured, people get shackled, people escape, people steal vehicles etc.

In the forbidden land our heroes meet a people who are a hybrid of Numen and Olmen. They have an archive of information about the past, and we learn (despite the illustration which shows three moons in the sky) that this story is set on a post-apocalyptic Earth. The Numen are descendants of people who were mutated by the radiation of the nuclear war, while the Olmen are descendants of people who hid deep underground during the period of the war and escaped exposure to radiation. The Olmen do not suffer the genetic defect that causes death in childbirth, and neither do children of mixed Olman and Numan parentage. Allyn, Keeven and Marva travel to the domed city of the Numen and with the help of the hybrids' psychic powers (the reality behind the rumor of super weapons) persuade the Numen to make peace with the Olmen.

The plot of this story is not bad, but it suffers in the style department and includes mistakes editors should have fixed. "Flaunted" is used in place of "flouted," which is embarrassing. When Allyn kisses Marva for the first time we are told she is "delicious as wild strawberries." How would Allyn know what wild strawberries taste like? On the same page Goldstein tells us the Numen eat only dehydrated foods and she presents a scene in which Allyn is "amazed" by how tasty fresh meat is. Maybe a scene in which he ate fresh fruit for the first time was excised?

Despite its problems, an acceptable entertainment.

"The Recalcitrant" (1954)

The intro to "The Recalcitrant" in Fantastic Universe tells us that "only a woman could have written this story..." that it has "compassion...high poetry...tenderness...[and] the breath of a fierce vitality...." Sure enough, the first paragraph is a bunch of gush about flowers, sunlight, and some chick's dream home!

But not to worry, the rest of the story is not like that. Jim and Alicia are a happily married couple, and over the twenty years of their marriage they have built their farm, house, and beautiful garden with their own hands. But today comes bad news! Jim tells Alicia that "some men" are coming to take him away, and he hides from them in the woods. He is eventually caught, but Jim's performance in the woods (he is very strong and indefatigable, for example) provides us clues that suggest Jim is a robot married to a woman from whom he has kept his true mechanical nature a secret! But when he is brought before the doctors who claim they want to help him, we learn that the truth is even more strange.

Jim is a cyborg, a human brain in a robot body. His body was wracked in a catastrophic war decades ago, a war that reduced the human population of the Earth to a mere half-million! So he could live as normal a life as possible, he was given this robot body, and something else--Alicia, a robot who thinks she is a real woman! But all those robotics were a temporary expedient--the doctors now have developed a real biological body for Jim, with which he can, in a relationship with a real human woman, father human children and help repopulate the ravaged Earth! But Jim is in love with Alicia, even if she is a machine, and resists being separated from his super strong robot body and the wife with whom he has built a happy life! (Alicia is slated to be reprogrammed to work like a drone in a factory!)

This story is pretty good--I was genuinely surprised when it was revealed that Jim was not really a robot and Alicia was. And, while the editor oversells the story, it is certainly noteworthy that both "The Recalcitrant" and "The Land Beyond the Flame" have at their centers obstacles to childbirth and parenthood--maybe Goldstein really does bring a female perspective to the traditional SF template of a melodrama* in which science causes and/or solves problems.

*"Melodrama" is the word Alexei Panshin uses to describe SF stories before the New Wave in his article of criticism in the December 1970 issue of Fantastic; I liked the article and like the word, which is more broad than a word like "adventure" and thus can comfortably encompass a story like "The Recalcitrant."

"Hour of Surprise" (1955)

The blurb on the first page of "Hour of Surprise" mentions motherhood, and I was excited to see the theme of parenthood carrying over from the last two stories. This story appeared in Fantastic Universe, whose editor Leo Margulies (echoing the sentiments he expressed about "The Recalcitrant") tells us it is "tender" and "lyrical."

Aram is a twelve-year-old boy living "Inside" with his two sisters and single brother and their metallic "Mother." His whole world is five rooms, but he knows an "Outside" exists, because Mother sometimes goes out there; when she returns her metal skin is cold, even though she has described "Outside" as a forbiddingly dangerous place of fire.

Mother has also set off limits a room into which she goes while the kids sleep; clever and curious Aram figures out how to gain access to the room and he discovers in there clues that suggest Mother is not their real mother and that they won't grow up to have metal skins themselves! Mother may in fact be a machine who is holding them captive because of some kind of human vs robot war! With the help of his eleven-year-old sister Aram manages to sneak Outside, where he learns the shocking truth (well, shocking to him; I guess it is more or less what we readers expected: the Earth was wrecked in an atomic war and Aram and his siblings, likely the only humans left alive, were left with Mother for safekeeping by their robot-building father.)

I liked it.

*********

I like old-fashioned SF stories, and these are competently executed, and Goldstein's theme of unusual or dangerous parenthood gives them a freshness and an emotional angle that touches our real life experience of having (and maybe even being!) a parent. I enjoyed all three of them and we'll read more Goldstein in our next blog post.

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Eight stories from the June 1957 issue of Fantastic Universe

If my calculations are correct, I paid $2.50 for my rapidly deteriorating copy of Fantastic Universe's June 1957 issue. In our last episode we read the stories in this magazine by people I knew something about already. Well, let's really get our money's worth and read the stories (eight of them!) by people about whom I know just about zilch.

"Holiday" by Marcia Kamien

In the little intro to this story the editor of Fantastic Universe tells us Kamien is a copywriter at a New York ad agency, is interested in Egyptian and Etruscan antiquities, and hates cats! Whoa, is this chick single? That is one sweet dating profile!

Four kids who have personal aircraft (just like 20th-century American kids had bicycles) tinker with the wires of their flying machines so they can go into "overdrive." When they are up in the stratosphere and activate the overdrive they warp into another dimension, one that horrifies them. This is when we realize these are alien kids--the crazy world they have arrived in has green grass and only one sun; it is our own world. The kids manage to warp back to their own dimension, and we readers are told that it is these sorts of childish hi-jinks that are the cause of UFO sightings on our Earth.

An acceptable four-page filler story. Kamien has three stories listed at isfdb, and "Holiday" is the last one. Maybe the cats got her?

"Day of Reckoning" by Morton Klass

isfdb tells us that Morton Klass is the younger brother of William Tenn (whose birth name is Philip Klass) and here in Fantastic Universe we learn he served in the Merchant Marine and is an anthropologist. Morton has a dozen credits at isfdb.

In 1966 the alien Rogg conquered the Earth! There were not very many of them, but the Rogg cunningly exploited the divisions among Earthmen and made us their slaves!

Forty-seven years have passed, and over the course of those long years of oppression the human race has cast aside its political and ethnic differences--finally, all men see each other as brothers! The Rogg are ejected from Earth, and a bright future of peace and unity awaits us!

I guess this is the kind of story you'd expect an anthropologist to write, utopianism with no foundation in reality or even logic. Acceptable filler, told in a series of flashbacks by the leader of the Earth rebellion as he presides over the Rogg surrender ceremony.

"First Landing" by Roger Dee

Roger Dee has a long list of story credits, and even a novel, at isfdb. I actually read a 1951 story by Dee, "The Watchers," back in 2015 and forgot all about it until this moment! I gave a thumbs down to that one, but maybe I'll like this one?

"First Landing" is a pretty traditional SF story about an astronaut who is sent to Venus to explore. The Earth is united under a singe government because a war broke out between the West and the commies and the commies got wiped out, and the remaining states united to pick up the pieces of a ravaged world. Our hero is on Venus looking for evidence of mineral resources the Earth sorely needs.

The astronaut encounters people on Venus he takes to be natives, naked bearded men who stand two-and-a-half feet tall and carry spears. He crashes his hover car in the Venusian fog and loses his weapons and it looks like he is at the mercy of these perhaps belligerent aliens, but the story has a happy ending--the "natives" are in fact Soviet cosmonauts who were secretly sent to Venus just before the war erupted that destroyed the USSR--the Reds manned their ship with people whom Dee calls "midgets" in order to save on food and fuel.

Even if the ending is a little disappointing I like all the stuff about Venusian ecology and orbits and calculating how much fuel is needed to get back to Earth and all that. Not bad.

"God of the Mist" by Evelyn Goldstein

This one has the kind of title you might see on a Conan or Grey Mouser story, and it reads a little like a violent and noirish Brackett planetary romance. (The MPorcius staff considers those good things.)

Venus has been colonized by the Earth; the primitive natives are like small beautiful children, and more or less at the mercy of the ruthless colonizers. Seven-foot tall Kohler is a human criminal, a murderer, on the run from the human police. When a tiny Venusian sees this huge slab of man meat he thinks it must be a god--Kohler looks just like the natural rock formation at his village which represents their god, Zanthu! Kohler makes his way to the village, looking forward to living the easy life of a local deity among his worshippers. He makes himself dictator of the village, callously killing those who question him. But his reign is not a long one--his own hubris and cruelty serve to guide the police to him and he suffers a rough justice. I was a little surprised that it was other Earthers who overthrew Kohler and not the natives--the Venusians in this story are pathetic victims, impotent to control their own destiny in the face of Earthmen's modern technology and organization and sheer size.

An OK story featuring surprisingly brutal violence against defenseless people. The editor's intro to "God of the Mist" informs us that Goldstein is a Brooklyn housewife, and isfdb lists nine stories by her--they all have adventurous sort of titles.

"Versus" by Edward D. Hoch

"Versus" by Edward D. Hoch

I recognize Hoch's name, but I don't think I have ever read anything by him. Wikipedia tells me that Hoch is a big wheel in the detective fiction game, but he produced enough SF stories to fill a 2015 collection entitled The Future is Ours. "Versus" appears in that collection, making "Versus" the only story we are reading today that was ever reprinted.

Unfortunately "Versus" is a sterile and gimmicky story with a gimmick so lame it barely qualifies as a gimmick. Al Zadig is an interstellar organized crime boss who manages illegal gambling operations as well as space piracy all over the galaxy. He bribes all the politicians and police authorities so his operations are not interfered with. Suddenly, one day, the government changes its policy and starts seizing Zadig's interstellar casino liners and shutting down his planet-based operations. A Mr. Snow comes calling; Snow explains that he is an even richer businessman than Zadig, and that after one of Zadig's pirate ships attacked the "space taxi" he was in, killing his wife, Snow devoted his fortune to destroying Zadig's crime empire. Snow's simple strategy has been to give bigger bribes to all the politicos and cops than Zadig has. If you were wondering what sort business Snow was in that he got so rich, he tells Zadig that "mine is an empire of good, of schools and hospitals and churches."

The anemic joke ending of this story is that when Zadig, driven to a desperate act of revenge, pulls a gun on Snow, the gun doesn't fire because Snow bribed Zadig's secretary to remove the rounds from the pistol's magazine.

Bewilderingly lame, like something a kid would write but without the gusto a kid might bring to a story about crime and revenge. Can it be that the most commercially successful writer I am reading today has written the worst story?

"Snakes Alive" by Henry D. Billings

This is Billings's sole credit at isfdb. This story consists mainly of radio transmissions between Dan Ellerman, best astrogater on the Galaxy Spaceways payroll, and ground control. Dan is the sole crewman aboard a ship ferrying a cargo of cobras from "space station one" to Luna. When Dan has to dodge an asteroid, the crate carrying the cobras falls over and breaks open and the motherfucking snakes are loose on the motherfucking rocket ship. The snakes were stowed in the compartment closest the cockpit, and lies between the cockpit and the compartment with rocket ship's firearms and medical kit. Not to fear--ground control transmits ultrasonic sound patterns which duplicate the effect of "the weird music" of "ancient Indian fakirs" and this pacifies the cobras so Dan can land safely on the Moon.

A waste of time.

"Rock and Roll on Pluto" by Hans Stefan Santesson (as by Stephen Bond)

This is one page of text and is not even a story, just a plotless anecdote. The colony on Pluto bans dancing and pop music, but some people go to the top of a mountain and play music and dance anyway.

This "story" was written by the editor of Fantastic Universe under a pseudonym. I guess he had a blank page and needed to fill it with something and found himself unable to sell or donate the it as ad space, and so produced this non sequitur.

(Hoch is off the hook--this is the worst story in the magazine.)

"My Martian Cousin" by Mark Reinsberg

"My Martian Cousin" by Mark Reinsberg

Reinsberg has ten stories listed at isfdb and was the book reviewer at Imagination for a little less than a year. He seems to have been an earnest reviewer--in the December 1953 issue of Imagination he gushes with unabashed love about The Space Merchants and also points out some shady practices of super-editor Donald Wollheim's. (I think Wollheim is great, but he certainly provides one opportunities to say "tsk, tsk.")

As its title might have led readers to expect, "My Martian Cousin" starts off as a sort of a comedy--I found it reminiscent of a TV sitcom. Our narrator is Kathy, an attractive Earth-born woman living in one of the domed colonies on Venus with her husband of nine years, Mike, one of the first humans to actually be born on Venus. Reinsberg, exploring the mysterious depths of female sexuality, has Kathy tell us she likes the way Mike's muscles ripple with energy when he is angry, and the story provides plenty of opportunities for Mike to get angry. As our narrative begins, the happy couple is at the spaceport waiting for Kathy's cousin, college girl Gerda, to get out of customs. It is taking forever because Martian-born Gerda, who invited herself like Edwige Fenech did in Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, brought along her pet Martian monster and the beast needs to be thoroughly decontaminated! Mike snarls that she should have just left the monster in quarantine--she is only going to be on Venus for three days! But when Mike sees Gerda for the first time (Kathy herself hasn't seen her for twelve years) she is, like Fenech's character in Sergio Martino's fourth giallo, unexpectedly gorgeous, and Kathy's irritable hubby changes his tune!

But not for long! Gerda is a hardcore Mars patriot who lives in a city of millions back on the Red Planet, and to her this tiny Venusian domed city is provincial, boring, primitive, and unsanitary. Everything on Mars, she assures everybody she meets, is better! (Gerda sounds like me when I moved from New York to Iowa!) Mike, a local big wig (he has one of city's eight aircar licenses and is an atmosphere scientist responsible for the air in the dome, the air that Greda insists is unhygenic), has to stand up for his home town and home planet, of course. Kathy is not much use at keeping the peace--Mars is currently at war with Earth, and Gerda's complaints of Earth tyranny (and the Martian dump that Gerda's pet monster takes on the carpet!) create just as much tension between the unwanted houseguest and the lady of the house.

All that stuff is amusing, but things get real (as the kids say) when the monster scratches one of Kathy and Mike's kids, it is discovered that somebody has sabotaged the dome (now who could that be?), and a drunken Gerda lets slip rumors about a Martian secret weapon that could exterminate life on Earth! How will Kathy and Mike respond to these crises?

This is a good story; the speculations about human life adapting to other planets and how human societies on different planets might interact are interesting, the humor stuff was actually humorous, and the way Kathy resolves the politics and war plot was clever--and it is all believable, the people feel like real people, not caricatures in an over-the-top satire or cartoonish superheroes in an action extravaganza. The story also includes tons of stuff for you feminists to pick over, with a female hero at odds with a female villain ("Short Essay: To what extent do Kathy and Gerda fulfill or defy stereotypes of women?") and lots about the narrator's relationship with her husband, her kids, and her larger society. "My Martian Cousin" reminded me of Heinlein's "The Menace From Earth," another 1957 story which combined descriptions of an extraterrestrial colony with a human interest drama (as with the Brackett comparison, we here consider that a compliment.)

**********

We've suffered through some lame pieces today in Fantastic Universe, but found a solidly good one in the Reinsberg story, while Dee and Goldstein also offer entertaining tales. I'm judging this exploration of one of SF's lesser periodicals to have been worthwhile.

"Holiday" by Marcia Kamien

In the little intro to this story the editor of Fantastic Universe tells us Kamien is a copywriter at a New York ad agency, is interested in Egyptian and Etruscan antiquities, and hates cats! Whoa, is this chick single? That is one sweet dating profile!

Four kids who have personal aircraft (just like 20th-century American kids had bicycles) tinker with the wires of their flying machines so they can go into "overdrive." When they are up in the stratosphere and activate the overdrive they warp into another dimension, one that horrifies them. This is when we realize these are alien kids--the crazy world they have arrived in has green grass and only one sun; it is our own world. The kids manage to warp back to their own dimension, and we readers are told that it is these sorts of childish hi-jinks that are the cause of UFO sightings on our Earth.

An acceptable four-page filler story. Kamien has three stories listed at isfdb, and "Holiday" is the last one. Maybe the cats got her?

"Day of Reckoning" by Morton Klass

isfdb tells us that Morton Klass is the younger brother of William Tenn (whose birth name is Philip Klass) and here in Fantastic Universe we learn he served in the Merchant Marine and is an anthropologist. Morton has a dozen credits at isfdb.

In 1966 the alien Rogg conquered the Earth! There were not very many of them, but the Rogg cunningly exploited the divisions among Earthmen and made us their slaves!

Forty-seven years have passed, and over the course of those long years of oppression the human race has cast aside its political and ethnic differences--finally, all men see each other as brothers! The Rogg are ejected from Earth, and a bright future of peace and unity awaits us!

I guess this is the kind of story you'd expect an anthropologist to write, utopianism with no foundation in reality or even logic. Acceptable filler, told in a series of flashbacks by the leader of the Earth rebellion as he presides over the Rogg surrender ceremony.

"First Landing" by Roger Dee

Roger Dee has a long list of story credits, and even a novel, at isfdb. I actually read a 1951 story by Dee, "The Watchers," back in 2015 and forgot all about it until this moment! I gave a thumbs down to that one, but maybe I'll like this one?

"First Landing" is a pretty traditional SF story about an astronaut who is sent to Venus to explore. The Earth is united under a singe government because a war broke out between the West and the commies and the commies got wiped out, and the remaining states united to pick up the pieces of a ravaged world. Our hero is on Venus looking for evidence of mineral resources the Earth sorely needs.

The astronaut encounters people on Venus he takes to be natives, naked bearded men who stand two-and-a-half feet tall and carry spears. He crashes his hover car in the Venusian fog and loses his weapons and it looks like he is at the mercy of these perhaps belligerent aliens, but the story has a happy ending--the "natives" are in fact Soviet cosmonauts who were secretly sent to Venus just before the war erupted that destroyed the USSR--the Reds manned their ship with people whom Dee calls "midgets" in order to save on food and fuel.

Even if the ending is a little disappointing I like all the stuff about Venusian ecology and orbits and calculating how much fuel is needed to get back to Earth and all that. Not bad.

"God of the Mist" by Evelyn Goldstein

This one has the kind of title you might see on a Conan or Grey Mouser story, and it reads a little like a violent and noirish Brackett planetary romance. (The MPorcius staff considers those good things.)

Venus has been colonized by the Earth; the primitive natives are like small beautiful children, and more or less at the mercy of the ruthless colonizers. Seven-foot tall Kohler is a human criminal, a murderer, on the run from the human police. When a tiny Venusian sees this huge slab of man meat he thinks it must be a god--Kohler looks just like the natural rock formation at his village which represents their god, Zanthu! Kohler makes his way to the village, looking forward to living the easy life of a local deity among his worshippers. He makes himself dictator of the village, callously killing those who question him. But his reign is not a long one--his own hubris and cruelty serve to guide the police to him and he suffers a rough justice. I was a little surprised that it was other Earthers who overthrew Kohler and not the natives--the Venusians in this story are pathetic victims, impotent to control their own destiny in the face of Earthmen's modern technology and organization and sheer size.

An OK story featuring surprisingly brutal violence against defenseless people. The editor's intro to "God of the Mist" informs us that Goldstein is a Brooklyn housewife, and isfdb lists nine stories by her--they all have adventurous sort of titles.

"Versus" by Edward D. Hoch

"Versus" by Edward D. HochI recognize Hoch's name, but I don't think I have ever read anything by him. Wikipedia tells me that Hoch is a big wheel in the detective fiction game, but he produced enough SF stories to fill a 2015 collection entitled The Future is Ours. "Versus" appears in that collection, making "Versus" the only story we are reading today that was ever reprinted.

Unfortunately "Versus" is a sterile and gimmicky story with a gimmick so lame it barely qualifies as a gimmick. Al Zadig is an interstellar organized crime boss who manages illegal gambling operations as well as space piracy all over the galaxy. He bribes all the politicians and police authorities so his operations are not interfered with. Suddenly, one day, the government changes its policy and starts seizing Zadig's interstellar casino liners and shutting down his planet-based operations. A Mr. Snow comes calling; Snow explains that he is an even richer businessman than Zadig, and that after one of Zadig's pirate ships attacked the "space taxi" he was in, killing his wife, Snow devoted his fortune to destroying Zadig's crime empire. Snow's simple strategy has been to give bigger bribes to all the politicos and cops than Zadig has. If you were wondering what sort business Snow was in that he got so rich, he tells Zadig that "mine is an empire of good, of schools and hospitals and churches."

The anemic joke ending of this story is that when Zadig, driven to a desperate act of revenge, pulls a gun on Snow, the gun doesn't fire because Snow bribed Zadig's secretary to remove the rounds from the pistol's magazine.

Bewilderingly lame, like something a kid would write but without the gusto a kid might bring to a story about crime and revenge. Can it be that the most commercially successful writer I am reading today has written the worst story?

"Snakes Alive" by Henry D. Billings

This is Billings's sole credit at isfdb. This story consists mainly of radio transmissions between Dan Ellerman, best astrogater on the Galaxy Spaceways payroll, and ground control. Dan is the sole crewman aboard a ship ferrying a cargo of cobras from "space station one" to Luna. When Dan has to dodge an asteroid, the crate carrying the cobras falls over and breaks open and the motherfucking snakes are loose on the motherfucking rocket ship. The snakes were stowed in the compartment closest the cockpit, and lies between the cockpit and the compartment with rocket ship's firearms and medical kit. Not to fear--ground control transmits ultrasonic sound patterns which duplicate the effect of "the weird music" of "ancient Indian fakirs" and this pacifies the cobras so Dan can land safely on the Moon.

A waste of time.

"Rock and Roll on Pluto" by Hans Stefan Santesson (as by Stephen Bond)

This is one page of text and is not even a story, just a plotless anecdote. The colony on Pluto bans dancing and pop music, but some people go to the top of a mountain and play music and dance anyway.

This "story" was written by the editor of Fantastic Universe under a pseudonym. I guess he had a blank page and needed to fill it with something and found himself unable to sell or donate the it as ad space, and so produced this non sequitur.

(Hoch is off the hook--this is the worst story in the magazine.)

"My Martian Cousin" by Mark Reinsberg

"My Martian Cousin" by Mark ReinsbergReinsberg has ten stories listed at isfdb and was the book reviewer at Imagination for a little less than a year. He seems to have been an earnest reviewer--in the December 1953 issue of Imagination he gushes with unabashed love about The Space Merchants and also points out some shady practices of super-editor Donald Wollheim's. (I think Wollheim is great, but he certainly provides one opportunities to say "tsk, tsk.")

As its title might have led readers to expect, "My Martian Cousin" starts off as a sort of a comedy--I found it reminiscent of a TV sitcom. Our narrator is Kathy, an attractive Earth-born woman living in one of the domed colonies on Venus with her husband of nine years, Mike, one of the first humans to actually be born on Venus. Reinsberg, exploring the mysterious depths of female sexuality, has Kathy tell us she likes the way Mike's muscles ripple with energy when he is angry, and the story provides plenty of opportunities for Mike to get angry. As our narrative begins, the happy couple is at the spaceport waiting for Kathy's cousin, college girl Gerda, to get out of customs. It is taking forever because Martian-born Gerda, who invited herself like Edwige Fenech did in Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, brought along her pet Martian monster and the beast needs to be thoroughly decontaminated! Mike snarls that she should have just left the monster in quarantine--she is only going to be on Venus for three days! But when Mike sees Gerda for the first time (Kathy herself hasn't seen her for twelve years) she is, like Fenech's character in Sergio Martino's fourth giallo, unexpectedly gorgeous, and Kathy's irritable hubby changes his tune!

But not for long! Gerda is a hardcore Mars patriot who lives in a city of millions back on the Red Planet, and to her this tiny Venusian domed city is provincial, boring, primitive, and unsanitary. Everything on Mars, she assures everybody she meets, is better! (Gerda sounds like me when I moved from New York to Iowa!) Mike, a local big wig (he has one of city's eight aircar licenses and is an atmosphere scientist responsible for the air in the dome, the air that Greda insists is unhygenic), has to stand up for his home town and home planet, of course. Kathy is not much use at keeping the peace--Mars is currently at war with Earth, and Gerda's complaints of Earth tyranny (and the Martian dump that Gerda's pet monster takes on the carpet!) create just as much tension between the unwanted houseguest and the lady of the house.

All that stuff is amusing, but things get real (as the kids say) when the monster scratches one of Kathy and Mike's kids, it is discovered that somebody has sabotaged the dome (now who could that be?), and a drunken Gerda lets slip rumors about a Martian secret weapon that could exterminate life on Earth! How will Kathy and Mike respond to these crises?

This is a good story; the speculations about human life adapting to other planets and how human societies on different planets might interact are interesting, the humor stuff was actually humorous, and the way Kathy resolves the politics and war plot was clever--and it is all believable, the people feel like real people, not caricatures in an over-the-top satire or cartoonish superheroes in an action extravaganza. The story also includes tons of stuff for you feminists to pick over, with a female hero at odds with a female villain ("Short Essay: To what extent do Kathy and Gerda fulfill or defy stereotypes of women?") and lots about the narrator's relationship with her husband, her kids, and her larger society. "My Martian Cousin" reminded me of Heinlein's "The Menace From Earth," another 1957 story which combined descriptions of an extraterrestrial colony with a human interest drama (as with the Brackett comparison, we here consider that a compliment.)

**********

We've suffered through some lame pieces today in Fantastic Universe, but found a solidly good one in the Reinsberg story, while Dee and Goldstein also offer entertaining tales. I'm judging this exploration of one of SF's lesser periodicals to have been worthwhile.

Saturday, December 15, 2018

1957 stories by Harry Harrison, Robert Bloch, Harlan Ellison, and Robert F. Young

I own eight or nine crumbling issues of Fantastic Universe, a magazine published from 1953 to 1959 by King-Size Publications and then for an additional year or so by Great American Publications. These SF artifacts were in lots I purchased that consisted mostly of the Ziff-Davis magazines Fantastic Adventures (published from 1939 to 1953) and Fantastic (published from 1952 to 1980); when I bought these lots I didn't realize Fantastic Universe had nothing to do with the Ziff-Davis magazines, partly because over the decades of its life the cover title of Fantastic would evolve back and forth between such variations as Fantastic Stories, Fantastic Science Fiction Stories, Fantastic Stories of Imagination, etc. I don't feel like this was a regrettable blunder or that I got ripped off or anything (even though the Wikipedia article on Fantastic Universe suggests critics think the magazine a piece of junk)--these magazines have art by people like Virgil Finlay and Emsh and stories by people whose work interests me, like Harry Harrison and Harlan Ellison and Robert Bloch.

Speaking of Finlay, Harrison, Ellison, and Bloch, let's start looking at my copies of Fantastic Universe with the June 1957 issue, which has a Finlay cover featuring an infantile-looking alien who has, apparently, just crashed his flying saucer in small town America. Is that his mother lying dead by the ship? Damn, this picture tells a tale of terrible tragedy!

Perhaps one reason the critics are so unfriendly to Fantastic Universe is that (if this issue is representative) it lacks editorials and a letters column; Ted White holds that a magazine should have a personality, a character, and a strong editorial voice and opinionated letters can develop such a personality, as well as creating a sense of community among magazine readers and the pros who put the magazine together. I have certainly enjoyed the editorials and letters in White's Fantastic. Well, with no such non-fiction material, let's get right to the stories in the June 1957 Fantastic Universe penned by the four authors whose work I already have at least a little experience with, the "short novels" by Harry Harrison and Robert Bloch, and stories by Harlan Ellison and Robert F. Young.

"World in the Balance" by Harry Harrison

Harrison of course is famous for a number of series (Stainless Steel Rat, Deathworld, Bill the Galactic Hero, and Eden are the ones I have some familiarity with) and influential individual works, like the source material for the Charlton Heston/Edward G. Robinson film Soylent Green. Harrison's work is diverse in tone and topic, so I can't predict what "World in the Balance" might be like or how I will respond to it. The fact that, according to isfdb, "World in the Balance" has never been reprinted is not what anybody would call a good sign, however.

Italian-American John Baroni is a grad student in physics at a New England university, and a veteran of house-to-house infantry combat in Italy in World War II. He and his Japanese-American girlfriend Lucy Kawai and their professor, Dr. Steingrumer, are in the lab conducting experiments on a device that makes things disappear when aliens invade the Earth! (I'm guessing Harrison deliberately chose the ethnicities of all the characters with an eye to undermining any prejudices readers might have related to WWII.) John snatches up a bolt-action rifle from the ROTC supply and uses the skills he learned in Italy to sneak into town and see what the hell is going on!

The hideous crustacean-faced aliens are using captured Earth weapons to exterminate police and military personnel (as well as any civilians who resist) and John uncovers why the invaders are able to so effectively achieve surprise on G.I. Joe and the boys in blue--the aliens are masters of cosmetic surgery and have, over the past few years, been replacing people in authority in government with alien impostors! The chief of police in the town by the school, an alien in disguise, lines up "his" men for a briefing and then mows them down with an automatic weapon! The Earth has had it, because the aliens have taken control of the world's stockpiles of nuclear weapons before we even knew we were in a fight and they nuke Washington, D.C. and anywhere else human leadership might organize a cohesive defense!

But wait! All is not (quite) lost! John realizes that the doohickey he and his fellow physicists are working on is a device that can send you back in time to another time line! He goes back in time a few weeks and sneaks around the Washington, D.C. area using gruesome means to figure out who in authority is a damned ET and who is a red-blooded Earther and then helps legit government officials to organize a spoiling attack that catches the aliens before they are ready to spring their own surprise attacks. The Earth in that time line is saved! Ad for our time line...well, that's the way the cookie crumbles, I guess.

A competent SF adventure story that delivers standard SF fare like malevolent aliens and time-traveling eggheads who get us out of a jam with technology and logical reasoning with a large serving of gore on the side. You can call it pedestrian, but it went down easy and I liked it.

"Terror Over Hollywood" by Robert Bloch

Psycho-scribe Bloch's story here would be reprinted in the 1965 collection Tales in a Jugular Vein. The cover of the 1970 British edition of this collection seems to be the culmination of a series of regrettable artistic choices.

According to Wikipedia, Bloch's 1982 novel Psycho II was a harsh critique of Hollywood, and this 1957 story suggests that Bloch's hostility to Hollywood is of long standing. From the first page of "Terror Over Hollywood" Bloch hammers at the theme that being in Hollywood has a powerfully negative effect on people's morals, that the inhabitants of tinsel town are fake phony frauds, heroin addicts and homosexuals who commit suicide at epidemic rates. (Makes me glad I have been spending most of my life in such bastions of decorum, decency and mental health as New York City and Washington D.C.!)

Kay Kennedy is determined to be a star, and has been so determined since the age of six! She convinced her parents to move to California and to work themselves to death financing her acting lessons, and since their demise she has (it is implied) been selling her body to important Hollywood types to advance her career. She has noticed that the very acme of Hollywood luminaries, the top ten or twelve actors and producers and directors who seem to call the shots in La La Land, don't seem to lose their looks or stamina as they age, and she tries to wheedle the answer out of our narrator, independent producer Ed Stern. As the story unfolds the tenacious Kennedy discovers the truth--Stern is a founding member of that tiny elite, the first beneficiary of the genius of a German scientist who can build a mechanical replica of a person's body that is almost indistinguishable from the original and then surgically remove that person's brain from its natural body and install it in the robot! Will Kennedy welcome a chance to sit at the top of the charts for twenty or thirty years and then enjoy a retirement that will last centuries, or react with horror at the prospect of never again sleeping, eating, drinking, or having sex?

This story is OK. I like that the narrator is the villain and his villainy is only hinted at for much of the story, and I like the brain-transplanting German mad scientist angle, but Bloch needlessly complicates things with a lot of talk of how the robot bodies need to go offline periodically and so during those periods Stern has to blackmail criminals who look like the stars into impersonating them, blah blah blah. (You'll remember that I also thought Bloch needlessly complicated the process of giving people eternal life in his 1951 story "The Dead Don't Die.") Bloch should have ditched the impersonation angle and focused on the Frankenstein stuff--ofttimes less is more, Robert, less is more.

"Commuter's Problem" by Harlan Ellison

I've done a lot of commuting in my life! (Maybe you have, too?) Thousands of rides on the New York City subway between the Upper East Side and Midtown, and before my apotheosis and after my exile, thousands of miles in automobiles between suburbs and universities and downtowns and shopping malls. The commute is one of the defining features of 20th-century middle-class life, the subject of song and story. And here is one of those stories.

Narrator John Weiler (I guess we're supposed to think "wheels?") uses cliches to describe himself and his life: "I'm a commuter--a man in the grey flannel suit, if you would....We keep up with the Jonses, without too much trouble." Every weekday, and some Saturdays and Sundays, too, he rides the train into Manhattan from Westchester County to work at his office. "There's something cold and impersonal about a nine-to-five job and a ride home with total strangers," he tells us. Then one morning he is walking through Grand Central Terminal, his face buried in a report, and he looks up to find he is lost. He's never seen this part of Grand Central before! Not only that, but the posters are in a weird foreign language and when he asks people for directions they speak in a weird foreign language! He gets caught up in a crowd and ends up on a subway car where he sees his odd neighbor Da Campo, the guy who doesn't watch TV and has a bizarre tentacled plant in his garden. Da Campo is amazed to see Weiler, and vaguely explains that this subway car goes to another planet!

Weiler gets the inside skinny once they arrive at Da Campo's home world of Drexwill twenty minutes and 60,000 light years later. Drexwill is an overcrowded urban conglomeration that many find uncomfortable, so middle class professionals like Da Campo (real name: Helgorth Labbula) commute to work in Drexwill and live incognito on less crowded planets like Earth. (The Drexwillians look just like Earth humans.) With bitter resignation Helgorth takes Weiler to the authorities, where Helgorth himself gets a stern talking to, as has lazy habits and flouting of rules (like the prohibition on cultivating Drexwillian vegetation on Earth) have played some role in Weiler's accidental one-way trip from Earth. Yes, one-way; the Drexwill government won't let Weiler go back to Earth! After talking his hosts out of executing him, Weiler finds a job on Drexwill; he realizes he would rather be on Drexwill than on Earth with his nagging wife and stressful job.

This story is just OK, a piece of filler that feels like something Ellison pounded out and submitted without much planning beforehand or revising after pulling that first draft out of the typewriter. Ellison neither put much thought into the whole system of aliens commuting between Earth and Drexwill, nor put much effort into setting up Weiler's abandonment of Earth--for example, Weiler's wife and job don't seem really that annoying, and in the beginning of the story Weiler doesn't really complain about them. Instead of writing a story exploring or explaining or dramatizing how suburban life and commuting suck, Ellison just takes this attitude for granted (note the use of tired cliches as a cheap means of telling the audience what to think) and pretends it is the backbone of his pedestrian story about a guy who inexplicably finds himself in another world. (Bloch in "Terror Over Hollywood" makes an effort to show us how bad life in Hollywood is, here Ellison just tells us how bad life is in suburbiua.) The story's tone is uneven; the first half of "Commuter's Problem" focuses on Weiler's suspicion and fear of the Da Campo family inspired by their odd habits and creepy garden and feels like a horror story, but all the horror stuff is jettisoned in the second half, which is a nonsensical fantasy that feels like a wacky humor story, albeit one without any jokes or laughs.

Barely acceptable. I am totally into stories in which guys hate their wives and jobs (I love Henry Miller's exhilarating Sexus, for example) and SF stories in which a guy struggles to survive in an alien milieu, but Ellison just gestures towards writing those sorts of stories here.

However mediocre I may have found it, "Commuter's Problem" was included in the oft-reprinted collection Ellison Wonderland, AKA Earthman, Go Home!

"Ape's Eye View" by Robert F. Young

In the tiny little intro the editor provides for this story we learn that the cover of this issue was inspired by "Ape's Eye View." Alright, let's learn what that Virgil Finlay illustration is all about!

"Ape's Eye View" is an explicit homage to Edgar Rice Burroughs's immortal creation, Tarzan. One day a meteor lands in a small rural town; apparently coincidentally, a local childless couple takes in a foundling soon after. This kid looks odd and is a terrible student and wretched athlete, and is bullied by the other kids and, as a teen, is disgusted instead of intrigued by the opposite sex. Shortly after achieving adulthood he vanishes when a large "entity" appears out of the sky and, eye witnesses report, consumes him. Our narrator, a schoolmate of the weird foundling, his thought processes triggered by coming across a copy of Tarzan of the Apes, surmises that this kid was a shipwrecked alien and that mysterious "entity" was a rescue ship come to bring the kid back to his home planet.

This is a modest but successful story that looks at the Mowgli archetype from a different point of view. Of the four stories I am talking about today it is the most original and the one that feels least like filler rushed out the door to make a buck. I like it. It looks like it was never published elsewhere, however.

**********

While not great, these stories aren't all that bad. We'll explore more of Fantastic Universe in the next installment of MPorcius Fiction Log.

Speaking of Finlay, Harrison, Ellison, and Bloch, let's start looking at my copies of Fantastic Universe with the June 1957 issue, which has a Finlay cover featuring an infantile-looking alien who has, apparently, just crashed his flying saucer in small town America. Is that his mother lying dead by the ship? Damn, this picture tells a tale of terrible tragedy!

Perhaps one reason the critics are so unfriendly to Fantastic Universe is that (if this issue is representative) it lacks editorials and a letters column; Ted White holds that a magazine should have a personality, a character, and a strong editorial voice and opinionated letters can develop such a personality, as well as creating a sense of community among magazine readers and the pros who put the magazine together. I have certainly enjoyed the editorials and letters in White's Fantastic. Well, with no such non-fiction material, let's get right to the stories in the June 1957 Fantastic Universe penned by the four authors whose work I already have at least a little experience with, the "short novels" by Harry Harrison and Robert Bloch, and stories by Harlan Ellison and Robert F. Young.

"World in the Balance" by Harry Harrison

Harrison of course is famous for a number of series (Stainless Steel Rat, Deathworld, Bill the Galactic Hero, and Eden are the ones I have some familiarity with) and influential individual works, like the source material for the Charlton Heston/Edward G. Robinson film Soylent Green. Harrison's work is diverse in tone and topic, so I can't predict what "World in the Balance" might be like or how I will respond to it. The fact that, according to isfdb, "World in the Balance" has never been reprinted is not what anybody would call a good sign, however.

Italian-American John Baroni is a grad student in physics at a New England university, and a veteran of house-to-house infantry combat in Italy in World War II. He and his Japanese-American girlfriend Lucy Kawai and their professor, Dr. Steingrumer, are in the lab conducting experiments on a device that makes things disappear when aliens invade the Earth! (I'm guessing Harrison deliberately chose the ethnicities of all the characters with an eye to undermining any prejudices readers might have related to WWII.) John snatches up a bolt-action rifle from the ROTC supply and uses the skills he learned in Italy to sneak into town and see what the hell is going on!

The hideous crustacean-faced aliens are using captured Earth weapons to exterminate police and military personnel (as well as any civilians who resist) and John uncovers why the invaders are able to so effectively achieve surprise on G.I. Joe and the boys in blue--the aliens are masters of cosmetic surgery and have, over the past few years, been replacing people in authority in government with alien impostors! The chief of police in the town by the school, an alien in disguise, lines up "his" men for a briefing and then mows them down with an automatic weapon! The Earth has had it, because the aliens have taken control of the world's stockpiles of nuclear weapons before we even knew we were in a fight and they nuke Washington, D.C. and anywhere else human leadership might organize a cohesive defense!

But wait! All is not (quite) lost! John realizes that the doohickey he and his fellow physicists are working on is a device that can send you back in time to another time line! He goes back in time a few weeks and sneaks around the Washington, D.C. area using gruesome means to figure out who in authority is a damned ET and who is a red-blooded Earther and then helps legit government officials to organize a spoiling attack that catches the aliens before they are ready to spring their own surprise attacks. The Earth in that time line is saved! Ad for our time line...well, that's the way the cookie crumbles, I guess.

A competent SF adventure story that delivers standard SF fare like malevolent aliens and time-traveling eggheads who get us out of a jam with technology and logical reasoning with a large serving of gore on the side. You can call it pedestrian, but it went down easy and I liked it.

"Terror Over Hollywood" by Robert Bloch

Psycho-scribe Bloch's story here would be reprinted in the 1965 collection Tales in a Jugular Vein. The cover of the 1970 British edition of this collection seems to be the culmination of a series of regrettable artistic choices.

According to Wikipedia, Bloch's 1982 novel Psycho II was a harsh critique of Hollywood, and this 1957 story suggests that Bloch's hostility to Hollywood is of long standing. From the first page of "Terror Over Hollywood" Bloch hammers at the theme that being in Hollywood has a powerfully negative effect on people's morals, that the inhabitants of tinsel town are fake phony frauds, heroin addicts and homosexuals who commit suicide at epidemic rates. (Makes me glad I have been spending most of my life in such bastions of decorum, decency and mental health as New York City and Washington D.C.!)

Kay Kennedy is determined to be a star, and has been so determined since the age of six! She convinced her parents to move to California and to work themselves to death financing her acting lessons, and since their demise she has (it is implied) been selling her body to important Hollywood types to advance her career. She has noticed that the very acme of Hollywood luminaries, the top ten or twelve actors and producers and directors who seem to call the shots in La La Land, don't seem to lose their looks or stamina as they age, and she tries to wheedle the answer out of our narrator, independent producer Ed Stern. As the story unfolds the tenacious Kennedy discovers the truth--Stern is a founding member of that tiny elite, the first beneficiary of the genius of a German scientist who can build a mechanical replica of a person's body that is almost indistinguishable from the original and then surgically remove that person's brain from its natural body and install it in the robot! Will Kennedy welcome a chance to sit at the top of the charts for twenty or thirty years and then enjoy a retirement that will last centuries, or react with horror at the prospect of never again sleeping, eating, drinking, or having sex?

This story is OK. I like that the narrator is the villain and his villainy is only hinted at for much of the story, and I like the brain-transplanting German mad scientist angle, but Bloch needlessly complicates things with a lot of talk of how the robot bodies need to go offline periodically and so during those periods Stern has to blackmail criminals who look like the stars into impersonating them, blah blah blah. (You'll remember that I also thought Bloch needlessly complicated the process of giving people eternal life in his 1951 story "The Dead Don't Die.") Bloch should have ditched the impersonation angle and focused on the Frankenstein stuff--ofttimes less is more, Robert, less is more.