"To Walk a City's Street" (1972)

"To Walk a City's Street" was first published in Robert Hoskins's anthology Infinity Three--Simak gets top billing on the cover, his name appearing above the famous Robert Silverberg and MPorcius fave Barry Malzberg! I own a copy of Infinty Three and that is where I am reading it; "To Walk a City's Street" was also selected by Donald Wollheim and Arthur Saha for DAW's 1973 Annual World's Best SF.

"To Walk a City's Street" was first published in Robert Hoskins's anthology Infinity Three--Simak gets top billing on the cover, his name appearing above the famous Robert Silverberg and MPorcius fave Barry Malzberg! I own a copy of Infinty Three and that is where I am reading it; "To Walk a City's Street" was also selected by Donald Wollheim and Arthur Saha for DAW's 1973 Annual World's Best SF.This is a brief story written in a spare straightforward style, consisting mostly of dialogue. Ernie Foss is a man of low intelligence, a petty thief who was living hand to mouth in a slum four or five years ago when government researchers realized he has a strange gift--he emits an aura which cures people of illnesses and prevents disease. The government scientists studied him and tried to figure out how his beneficial power, which was absolutely out of the dimwit's control, worked, but their efforts were in vain. So they decided that the thing to do was to drive Ernie around the country, to compel him to walk around in slums all over the United States, helping improve the health of our nation's most vulnerable citizens. This weird health campaign is kept a secret from the press and public.

We learn all this gradually as the story, which describes one night in Ernie's life, unfolds. Ernie does not like travelling the country with government agents who tell him where to go and watch him ceaselessly, and he tries without success to escape. One of the themes the story brings up is to what extent each of us is responsible to everybody else, to what extent the government can abridge your freedom in its pursuit of the common good.

This story also has a twist ending ("To Walk a City's Street" is the kind of story that reminds me of TV's Twilight Zone.) It seems that Ernie's aura kills germs and viruses, with the result that people in his vicinity don't get sick, but also plants the seeds of a deadly affliction that strikes five years after contact with Ernie--all the people from his old neighborhood are suddenly keeling over. What will the four agents who are chaperoning Ernie do now, knowing that they are doomed and Ernie is a public menace and other government agents may soon be after them to make sure they don't blab to the world the government's horrible blunder?

I like it.

"The Ghost of a Model T" (1975)

|

| Hardcover edition |

Hank is an old man, walking home from the bar, alone, never having married, his dog having died, only his lonely house awaiting him. He is reminiscing about the good old days before all the taxes and regulations of today, when machines were simpler, like his Model T. He can still hear the distinctive sound of that Model T....

A Model T pulls up next to him, one without a driver. It drives itself, this machine, and it takes Hank all over the country of his youth, where he drinks moonshine and dances in a barn with the kind of youngsters he danced with in his own youth, then meets his old friend Virg, a man who, like Hank, failed to marry and amounted to little. The Model T carries the two all over the country, to Chicago and New York and New Orleans, in a version of the USA where it is always 3:00 AM and Hank and Virg's bottle of moonshine never runs out and they need never stop to eat or sleep. For Hank and Virg, this is Heaven.

In his afterword Simak admits that this is an exercise in nostalgia, that he considers the 1920s, in some ways at least, a better time than the decades that succeeded it, more innocent and simple, and the Model T a symbol of that age.*

This is a successful mood piece, marginally good, but no big deal. It is easy to enumerate the many ways life was better in 1975 than 1925, but I find it just as easy to sympathize with Simak's nostalgia for the period of his youth (Simak was born in 1904 and so experienced the Twenties first hand as a young man)--every day I look back from my current situation (AKA "the living death") to my New York days and am not sure if I feel like those days were a beautiful dream and this the sterile reality or this suburban life a monotonous monochrome nightmare into which I fell the day I left the Upper East Side.

*I swear that it is mere coincidence that I read "The Ghost of a Model T" the same day the wife and I sold our 2006 Toyota Corolla and bought a 2019 Toyota Corolla and I realized with a groan that all the radar and camera safety features on the new car were not going to lower our insurance rates by rendering driving safer, as I had naively assumed, but increase them by complicating any potential repairs.

"Party Line" (1978)

"Party Line" is set in a future of video phones and an emerging population of telepaths who may well be the harbingers of a new human species. A government program has these telepaths communicating with various races of intelligent aliens--it is the hope of the feds and the taxpayers that from these aliens we can learn how to build an FTL drive and other technologies that will improve our lives, but talking with the aliens is not that simple. The program is twenty-five years old and a usable means of FTL travel is nowhere in sight, and the Congress is thinking of cutting funding.

This story is largely made up of conversations that reveal to us readers the high hopes and meager results of the project and the vague and frustrating communications of the telepaths with the aliens. A primary theme of "Party Line" is the idea that extra terrestrials will be so alien that they will be close to inscrutable, and that they will find us equally difficult to fathom. It is normal in SF for relationships between Earthpeople and aliens to be based on Earth history; the aliens may be oppressed victims of Earth colonizers meant to evoke North American or African natives, or dangerous ideological foes analogous to the Nazis or communists. We also commonly see aliens who are like gurus eager to lead us to salvation. In contrast, in stories like "Party Line," as well as "Dusty Zebra" and "The Golden Bugs," which we looked at in our last post, Simak makes the point that aliens will not just be "funny-looking humans" whom we will deal with the way the English dealt with the Iroquois or the Masai or the Germans, or even messiahs who can lead us fallen Earthlings to enlightenment--they will be so different from humans, their ways of thinking and living so foreign, that communication will face nigh insurmountable hurdles.

While human relationships with aliens in "Dusty Zebra" and "The Golden Bugs" are dead ends and those stories end on ironic notes, "Party Line" leaves its characters and readers with a strong sense of hope. Some of the telepaths, by setting aside their fears and prejudices (and convincing the aliens to set aside some of theirs) begin to make progress in their interstellar cross-cultural discussions, and the head of the project has reason to believe that breakthroughs--new knowledge, including the key to an FTL drive--are forthcoming, giving him confidence that he can win continued funding from Congress.

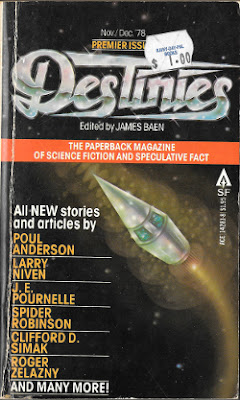

Like "Ghost of a Model T" a successful, if not spectacular, story. Since 1978 it has been reprinted in Simak collections with covers approximately as bland and boring as the one on the first issue of Destinies. (My big gripe with Destinies is not the cover art but the font of all the interior text, which is too wide, so that the letters are distractingly squat and ugly.)

**********

These stories were all worth my time. More Simak in the future, but first we'll dig through my magazines and anthologies and see what else of interest turns up.

The first Clifford Simak story I read as a kid was "The Big Front Yard." Loved it! I sought out Simak's other work. My favorite Simak novel is WAY STATION, but I haven't read all his later SF novels. There may be treasures waiting for me!

ReplyDelete