"A Tragedy of Errors" by Poul Anderson

isfdb lists this one as being part of the Technic Civilization series, and it has been reprinted in the collections The Long Night (in the 1980s) and Flandry's Legacy (in our own crazy 21st century) among a few other places. I'm reading the magazine version of "A Tragedy of Errors," which is graced with four illustrations of space craft and people in space suits by Gray Morrow, though I am consulting a scan of the Sphere edition of The Long Night when I come upon a confusing typo, like a "have" on page 14 of the magazine where I would expect to see a "haven't." (The book version has "haven't.")

"A Tragedy of Errors" takes place in "The Long Night," the time period after the collapse of the Terran space empire when the human race, now inhabiting thousands of star systems, becomes fragmented, people having lost the ability to build space ships and repair many of their electronic systems, though surviving space ships can still be operated on manual, though at additional risk and lesser efficiency. Our hero is Roan Tom of planet Kraken, who, I guess Viking-like, travels hither and thither in a space ship, raiding and trading as he sees fit. He has multiple wives and lots of tattoos. Anderson spends perhaps too much time describing what he and the two of his wives that appear in the story look like--Anderson loves to describe stuff, sunsets and the wind in the trees and that sort of thing.

The plot of "A Tragedy of Errors," which is like 56 pages or so here in Galaxy, concerns Tom and the two wives he has with him, one the chief wife he's been with for quite a while, a seasoned spacer with whom he has grandchildren, and the other a new acquisition, young and inexperienced, having to land on a planet hoping it has the industrial capacity to repair their damaged ship. They find the natives are very wary of strangers, having been raided in the recent past; the central gimmick of the story is that the English language has evolved differently in different spots since human civilization fell into isolated pockets with the collapse of the Empire, and this makes negotiations between Tom and the locals difficult and leads to bloodshed.

Our heroes get split up, the women fleeing the crash-landing site of Tom's ship into the wilderness while Tom tries to negotiate with a member of xenophobic local aristocracy. The older wife, many adventures behind her, teaches the younger city-bred wife how to survive, and the younger grows as a person in response to the challenges she faces. Tom uses logic and his practical knowledge of science and technology to reunite with his wives, and then the younger wife uses her book-learned science knowledge and facility with math to figure out the mystery of this star system's age and this planet's erratic weather, information Tom sells to the local potentate as part of his negotiations to make peace and lay the foundations of a mutually beneficial commercial relationship. In the denouement we find the younger wife becomes a successful diplomat.

I still enjoy reading about and thinking about aircraft, spacecraft, spacesuits with anti-grav so you can fly around in the atmosphere like a bird and that sort of thing, and Anderson delivers on that fun stuff. He also includes lots of astronomy, sociology and ecology stuff, always telling you that this or that geographic or meteorological feature is the result of the proximity of this moon or elevated solar radiation or whatever, and always offering speculations on how people who live in the ruins of the superior civilization of their ancestors might think and behave. "A Tragedy of Errors" is adventure fiction about people fighting and trying to evade capture or escape captivity, but it is also serious science fiction informed by Anderson's knowledge of science and history and full of little lectures. And there is a plus for our feminist friends--Tom's wives are instrumental in resolving both the action and the number-crunching obstacles presented by the plot.

I can mildly recommend "A Tragedy of Errors." You might justly call it an unspectacular standard-issue Anderson space story, but it is competently told and I appreciate its pro-science and pro-trade values, and I enjoyed it.

"The Planet Slummers" by Terry Carr and Alexei Panshin

In the course of this blog's apocalyptic life we've read Terry Carr's stories "Castles in the Stars," "The Dance of the Changer and the Three," and "In His Image," as well as Carr's novel Cirque. As for Alexei Panshin, we've read "The Destiny of Milton Gomrath" and "Now I'm Watching Roger." (I'll also note that, before starting this blog, I read Panshin's famous Rite of Passage and really liked it.) "The Planet Slummers" is four and a half pages long and seems to never have been reprinted. We're all about the deep cuts here at MPorcius Fiction Log.

"The Planet Slummers" is an absurdist joke story perhaps set in another universe--in the first column we learn that our protagonists, Dave and Annie, have purchased an Edsel with a "Dewey for President" sticker on it and driven it to England. The core joke of the story is that Dave and Annie and their circle of friends are hipsters who buy things "ironically"--D & A have a picture of Mussolini in their house with a joke word balloon affixed to it, for example, while a friend who bought a pet bandicoot did so because he thought "bandicoot" sounded funny. After we see these two jokers in action at a rummage sale, a UFO lands near them and they are accosted by a pair of space aliens who are just like they are--these E.T.s are frivolous people who collect stuff not because they admire it or can make use of it but because they think it is funny. The aliens seize Annie because they think she is amusing and fly off with her, leaving Dave on Earth to worry that, like that bandicoot, she is doomed to some black fate when the aliens find something funnier.

For what it is, "The Planet Slummers" actually works--Dave and Annie, and the two aliens, actually sound and act like the sort of people Carr and Panshin are spoofing--I know these sorts of people, and my wife and I, who, as my twitter followers may have noticed, spend a lot of time at antique stores and flea markets, might even be considered akin to these sorts of people. So even though this is a trifling joke story I'll give it a grade of "acceptable."

"Crazy Annaoj" by Fritz Leiber

Many a time at this blog I have noted the somewhat unusual sex content in Fritz Leiber stories, and today I get to do so again. Sadly, I also have to tell you that "Crazy Annaoj" is a rather weak story in which little takes place and which lacks any compensatory charms, the style and images and relationships and jokes being quite bland. I guess we can call it acceptable.It is the far future when mankind has explored multiple galaxies and colonized untold numbers of worlds. The richest man in the human race, Piliph Foelitsack, is like 400 years old, but looks and even mostly acts like he is in his early 20s because he's had so many treatments and his body is full of gadgets which a team of doctors aboard his space ship Eros monitor and control remotely 24/7. He has just married his seventeenth wife, Annaoj, a woman 17 years old who managed to catch his attention when she was a 16-year-old beauty-contest-winner and actress in a virtual reality porno film. Piliph is the richest man in human civilization, having risen out of a ghetto to become owner of multiple planets and a fleet of hyperspace freighters. Wife #17 Annaoj was born in a slum herself and her drive, intelligence and ambition are comparable to his.

On their honeymoon the couple visit a gypsy fortuneteller. One of the themes of this little story is that no matter how scientific, no matter how high-tech, a civilization may be, many of its members will be fascinated by the supernatural and the occult, and will act irrationally when it comes to love and sex.

The gypsy tells the bazillionaire that he is young and his longest journeys lie ahead of him. Piliph and Annaoj don't believe her--Piliph has travelled widely across the universe but just recently decided to stick to the Milky Way galaxy from now on in order to remain close to the best health professionals and facilities. Just after leaving the gypsy, Piliph's body gives out and he collapses--the doctors freeze him in hopes that new technologies will be developed that can revive him.

Annaoj takes over Piliph's business empire and runs it as well--maybe better!--than did he, its founder. She also spends a lot of time travelling all over the universe, trying to find somebody with the ability to revive her husband, visiting not only the foremost scientific medical men but also witch doctors, mystics and sorcerers. Annaoj has sex with lots of men, but her heart remains with her husband, and oft are the times she will lay down to sleep next to his frozen body. The Eros carries her and her frozen husband to so many extragalactic locations over so many centuries that the gypsy's prediction comes true. After searching the universe for a way to revive her beloved for over 1,000 years, the Eros fails to return from one of its jumps into hyperspace, the ship and Annaoj vanishing.

This is one of those stories that I like more thinking back on it than I did while reading it. While I was reading "Crazy Annaoj" it felt slight and bland, but looking back the plot seems good--maybe I should say I feel the story is underdeveloped, that it is like a plot outline or summary that would benefit from fleshing out.

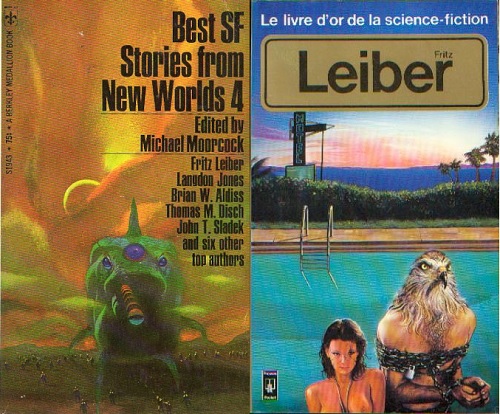

"Crazy Annaoj" has been reprinted in the Martin H. Greenberg, Charles G. Waugh and Jenny-Lynn Waugh anthology that has appeared under the titles 101 Science Fiction Stories and The Giant Book of Science Fiction Stories as well as Leiber collections. The covers of the collections suggest this story is both rare and one of Leiber's own favorites. Hmm.

**********

A decent batch of stories--any group of stories that doesn't include any bad ones is to be commended. But I'm not actually in love with any of them. Maybe love awaits us when we read the stories from this issue of Galaxy by Aldiss, Lafferty and Laumer. Fingers crossed!