"What've we got to fight them with?" asked Preston.

"Fight them?" said Job, almost shocked at the idea.

"Rifles," said Quick.

"Not big enough," said Preston with a shudder.

"Dynamite," said Warren. "We have dynamite."

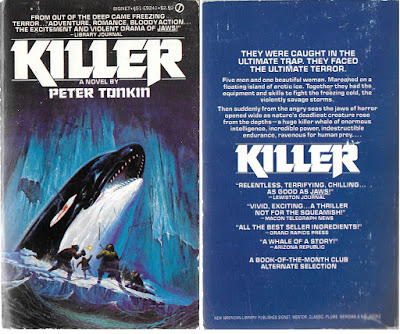

I bought 1979's

Killer, British thriller writer Peter Tonkin's first novel, because of the arresting cover painting, which depicts people in some Arctic hellscape fighting a killer whale of alarming proportions with, of all things, a bundle of dynamite! I don't usually read mainstream bestsellers, but I couldn't resist the gonzo promise of over the top action presented by the cover, and I often like those silly animals running amok movies like

Jaws,

Grizzly,

Frogs,

Orca, et al, the bastard children of that greatest of American novels,

Moby Dick.

(

Killer came out two years after Arthur Herzog's novel

Orca, which Wikipedia is telling me was the basis of the 1977 film. In my youth I read Herzog's

Make Us Happy, but all I can really remember of it are the scenes about the Sex Olympics.)

Killer (for days I haven't been able to stop singing that

Van Der Graaf Generator song about a depressed fish to myself) starts with a page full of excerpts from newspaper articles and Congressional testimony that purport to describe how the U. S. Navy trained dolphins to kill communist frogmen during the Vietnam War; lacking the opposable thumbs that have made us primates masters of the world, the dolphins killed Charlie using bayonets, “gas guns,” and “hypodermic needles connected to carbon-dioxide cartridges” that the Navy had helpfully strapped to their noses. Then comes a prologue (titled “Prelude”) in which a scientist explains in exacting detail (“He has a bite-width of three feet seven and a quarter inches.…He can swim at a top speed of twenty-five point eight knots….he’s six feet longer than a Spitfire...”) his work training a killer whale to a visiting admiral. The whale in question jumps out of the bay it is being trained to protect for Uncle Sam and devours the admiral (whose last thought is a regret that he quit smoking three weeks ago) and then escapes into the open sea. Then Tonkin gives us a page of quotes from Mary Shelly’s

Frankenstein and Thomas Carlyle’s

On Heroes and Hero-Worship.

I bought

Killer hoping it would be a harrowing adventure story and/or a crazy horror story, so it was with some disappointment that I began to suspect I was in for 232 pages of silly jokes and denunciations of American foreign policy and Western meddling with

sacred Mother Nature. Fortunately, the tone of the main narrative is quite different from the almost totally superfluous and unnecessary "prelude;"

Killer is a blood and guts tale of sickening violence and sudden death, just as I had hoped.

Katherine Warren is a 25-year old Englishwoman, a genius botanist and a striking beauty. Her father is also a genius botanist, but she hasn’t seen him in a decade because he’s always off at some exotic locale studying plants. Daddy doesn’t even know that Kate’s the #2 grad student in botany in the whole history of Oxford (Daddy himself is #1!) In hopes of finally getting to know her own father, Kate joins his expedition in Alaska, under a pseudonym, so she can surprise him. While the Warrens and the other members of the team are flying to their base camp from Anchorage, the private jet provided by their employers crashes mere yards from the icy Arctic seas, within sight of the killer whale who went AWOL in the prelude!

Also surviving the plane crash are Job the Eskimo, Colin Ross the expert on weatherization, Simon Quick the Arctic guide, and Hiram Preston the American co-pilot. Quick hates Ross because years ago his brother Robin (as well as Job's brother Jeremiah--the world of people who explore places that are fucking cold is a small one) was on an Antarctic expedition commanded by Ross, and the venture met disaster--Ross was practically the sole survivor! (Jeremiah also survived, but lost his legs and "manhood" and died soon after returning to civilization.) Quick's sister Charlie, who was married to Ross, fell into depression after this tragedy and committed suicide. Quick blames Ross for this devastating body count ("That's my whole family you killed") and the Antarctic fiasco is the topic of much conversation, Ross's nightmares, and flashbacks throughout the novel.

The stranded researchers expect help to come along soon, but then the plane explodes and this causes the ice sheet they are on to break off and start floating away from their last known position at like ten miles an hour. They are trapped on a twenty-acre ice raft, where for almost 200 pages and six days they struggle to survive as various Arctic animals (most prominently a pack of killer whales led by that rogue U. S. Navy veteran) threaten them, as well as an iceberg, rain, and warm water which whittle their raft down to size until it is almost too small to carry them. The characters utilize every weapon and piece of equipment at hand in their desperation, and, like in a slasher movie, they are gradually killed off until only Kate and Ross, who have of course fallen in love, are left alive!

Killer is marketed as a horror story, and includes plenty of gore: we get lots of spurting and dripping blood, cracking bones, and dramatic deaths. The pilot of the crashed plane, for example, is impaled on a tremendous icicle (

I can't encounter that word without suffering the compulsion to sing that Tori Amos song about masturbation to myself) that penetrates the cockpit, and Kate, unconscious at the time, is bathed in his gushing blood. The bizarre deaths are not limited to us bipeds--when the pack of killer whales attacks a blue whale, the hunters try to get inside the blue's mouth to rip out its tongue, and the blue closes his jaws, trapping one orca and crushing the life out of it. (One entire chapter, and several sections of other chapters, follow the killer whales' point of view as they fight other marine mammals.)

Besides the bloodshed Tonkin keeps the story interesting with lots of psychological jazz. Simon Quick can't forgive Ross and is always competing with him, though it is clear the author wants us to sympathize with Ross and see him as the better man. (Of Simon, the author tells us: "Like many people, his ability to convince himself that he was the true hero of every situation he was involved in, and to explain his mistakes and meannesses to his own satisfaction, was almost infinite.") Quick is also a sexist horndog who keeps staring at Kate's chest. Kate has her own daddy issues, and she also blames herself for the crash and explosion. Daddy Warren doesn't much care about his daughter, being a man of driving ambition who hides his will to power behind an absent-minded professor facade; he also suffers from agoraphobia.

As the novel proceeds, Tonkin springs on us shocking revelations about the characters. For example, when we meet Ross on page 19 we see he has a black glove on his left hand that he never takes off, even when he removes the matching glove from his right hand. During a polar bear attack on page 85 we discover Ross has an artificial left arm, reminding us readers of Ahab (you'll recall he had an artificial leg) and reminding Job of

one of the more prominent gods of the Inuit. Job, by the way, gets the role we so often see

non-whites play in popular fiction, that of the calm and wise guru, a sage who is "close to the nature" and is not only willing to share his knowledge of the Arctic and the legends of his people with the palefaces, but actually sacrifices himself to help them.

Its brisk pace, explicit and extravagant gore, interpersonal melodrama, and voluminous trivia about the Arctic and Antarctic make

Killer a smooth and entertaining read (if you aren't too squeamish!)

**********

Bound in my copy of

Killer was an ad with order form for the Doubleday Book Club. Click on the scans below to get a look at what books Doubleday was pushing back in the late '70s. (And admire that sweet tote bag!) Maybe I'm crazy, but while I would expect

Killer to appeal to male readers, this ad seems to be targeting women readers.

The only books displayed with which I have any personal familiarity would be the Betty Crocker cookbook (a later edition, however) and the Richard Scarry books. I loved Richard Scarry when I was little, especially his

drawings of weird aircraft and automobiles, like an insect-scaled bulldozer and a car shaped like an alligator.