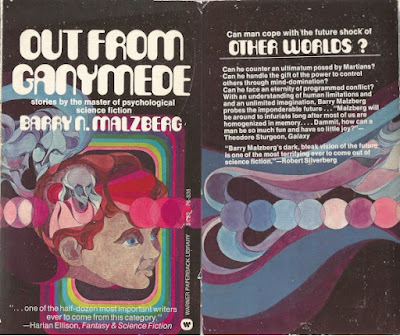

Today we'll bid our farewell to Out from Ganymede. Malzberg provides an introduction to the collection, dated "11 May 1973: New Jersey," in which he thanks a long list of editors, indicates he would love to write plays but there is no market for drama so his favorite medium by default is the short story, makes a joke about how writers love to drink, and admits that "Years ago I thought of myself as a writer disguised as a science-fiction writer....Now it is quite clear that I am an s-f writer." As I told you last time, I often find Malzberg's "mainstream," non-SF, work more enjoyable than his stories full of astronauts going crazy and crazy people donning hypnohelmets, so I am ambivalent about that last statement, and harbor hopes that today's four stories will go light on the SF elements.

|

| Squint or click to read gushing blurbs from Harlan Ellison, Theodore Sturgeon and Robert Silverberg |

"Beyond Sleep" (1970)

I absentmindedly reread this one, which I blogged about in 2013 when I read it in the copy of Marvin Kaye's Masterpieces of the Unknown that I bought at BookOff, the Japanese store in midtown Manhattan. Then I absentmindedly wrote the following superfluous description and assessment of the story. Then I realized I had already blogged about this one, then I marveled at how succinct my blog posts used to be, then I indulged in sad memories of the days when my errands would have me walking past Japanese stores instead of driving past herds of cows and sheep, and then I selfishly decided to not delete the two paragraphs below. Please enjoy.Two pages that originally appeared in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Our narrator dreams that he kills his nagging wife with a shiny knife, then he dreams that he used the knife to commit (or attempt?) suicide, then there is a dream that they are just getting a divorce (I think); in some scenes he is in prison dreaming, in others in the hospital, or just at home. What is real and what is strictly a dream? Who knows?The descriptions of blood and of the knife glittering in the light, as well as the narrator's frenzied dialogue in which he explains his horrifying actions to his wife, are good, so, I'm giving this one a thumbs up, though, yeah, it is basically filler.

"The Interceptor" (1972)

A man is hiding from the police in an uncomfortable hotel room in a drug-ridden slum part of town. He has been here for weeks. Malzberg splits the story into four main sections, each presenting a different scenario that explains why the man is hiding from the cops. In one, his business partner was having an affair with his wife, and when she killed the partner, she framed the protagonist. In another scenario, the wife has been killed by the business partner, etc. In the end of the story we realize that these scenarios are all fantasies of the main character, who has murdered his wife, his business partner, his doctor, and a police inspector, and enjoys concocting these mystery fiction plots in his mind, each time slotting different characters in the various roles of victim, perpetrator, and friend. Now he feels he needs some new characters for his little dramas, and plots to kill an employee of the seedy hotel.

Acceptable. "The Interceptor" first appeared in an issue of Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, and this time Malzberg's name appears on the cover. In 1979 the story was reprinted in a hardcover anthology of stories allegedly selected by Alfred Hitchcock himself as one of the director's faves.

"Agony Column" (1971)

"Agony Column" debuted in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and in 2013 was included in the famously typo-ridden The Very Best of Barry N. Malzberg--Barry or somebody at Nonstop Press must have really thought it was good.In New York City I worked for a government entity, and as such I had a lot of time on my hands, my office being unaccountable and unproductive, my direct superior rarely coming in and, when she did have something for me to do, it was usually something involving not the people's business but her personal business. One day, having heard that there was some proposal to have additional public funds directed to the institution where I was "working," I spent time in the otherwise untenanted office writing a letter to my local government representative, saying that by no means should additional money be sent to this institution, as I knew from first hand experience that the money was not needed and would be wasted. The response to my letter was a thank you for my support of the initiative to direct additional public funds to the entity which I had, in fact, denounced in my letter. Obviously the people in my representative's office did not actually read the letters they received, just mechanically sent form letters in response.

I tell you this boring true life story because "Agony Column" depicts a series of just such events. The entire story consists of correspondence, a New Yorker's letters to politicians and to magazines and the responses he receives, all of which indicate he has been ignored or misunderstood, just as happened to me. In his later letters, the letter writer expresses the belief that the bureaucratization of our society has lead to ordinary people being unheard and losing their identity; his final letter is to the President of the United States, declaring his intention to kill him.

OK, I guess.

"The Sense of the Fire" (1967(?))

isfdb and Wikipedia indicate this story debuted in the January 1967 issue of the men's magazine Escapade. But a note in my copy of Out from Ganymede says it debuted in the January 1968 issue of Escapade. Probably that is just a typo, but, just in case, I'll illustrate my musings here about "The Sense of the Fire" with the covers of both issues of Escapade; I'm definitely not including the '68 issue with Elke Summer because it is so elegant and modern and charming in contrast to the '67 issue which is so garish and cluttered and stupid."The Sense of the Fire" would later be printed in The Very Best of Barry N. Malzberg (under the title "The Wooden Grenade") and rightly so--it is a better than average Malzberg story, more vivid, more psychologically authentic, more carefully crafted and more believable than most of Malzberg's often broad, farcical, and fantastical work.

"The Sense of the Fire" is about Stein, a government worker who goes into slum apartment buildings to talk to people about their government benefits and remind them of their obligations. Stein carries with him a wooden practice grenade, which he caresses for comfort while on the job and stares at obsessively on his off hours. We are there as he does his work, talking to people with dreadful lives, and in flashbacks to Stein's disastrous stint in the Army we witness the disturbing events that have made him obsessed with hand grenades. The theme of the story is that all of our lives are terrible, that all of us, even the pretty office girls Stein saw from the Army recruiting station and even the contemptuous college kids Stein saw from the Army base where he is being trained, even the noncoms and officers who bossed Private Stein around, live lives of fear and suffering. While we are equal in our suffering, we are far from united--in fact, the behavior of the characters in the story--Stein perhaps most of all--demonstrates that most people shirk responsibility and manipulate and take advantage of others.

A good story with which to finish Out from Ganymede, and a story which buttresses my thesis that Malzberg's non-SF work is better than his SF work. Thumbs up!

**********

There are four pages of ads in the back of Out From Ganymede. First comes a full page ad for All the President's Men complete with blurb from Dan Rather. Then we get two pages of ads for SF books, though there are only three books plugged on the left hand page and two of them, Ron Goulart's The Gadget Man and Keith Laumer's A Trace of Memory, both appear on the right hand page as well. I always avoid Goulart because I suspect his work consists of unfunny satires; in 2019 I read a bunch of Laumer's short stories, including some Bolo stories, and I have to admit I don't remember much about them. The right hand page, oddly, lists Donald Wollheim's The Secret of the Ninth Planet twice; this is a book I own but have not yet read. At the top of the list of that right hand page is Poul Anderson's The Virgin Planet, which I reviewed positively in 2017, and in the middle, between the duplicative Wollheim entries, is John Jakes' On Wheels, which Joachim Boaz awarded three of five stars in a 2017 review of his own. Also advertised is The Best Science Fiction Stories of Clifford D. Simak, which includes "All the Traps of Earth," which I enjoyed back in 2021. The final page of Out From Ganymede advertises four mainstream books that appeal to your lust for sex and your fear of death: a "now-novel" about sex in New York; a novel about a journalist questioning his own manhood as he examines the life of an astronaut who was killed while on mankind's heroic quest for knowledge, as John W. Campbell, Jr., might put it, or wasting his time and the public dime sublimating his sexual frustration, as Barry N. Malzberg might put it; a novel about a New York Jew who becomes a titan of the organized crime world ("certain to take its place next to The Godfather"); and a book about how diet affects your psychology that tells you something about coffee that Juan Valdez won't tell you. Hopefully your "local dealer" has these in stock, because you might start having fits if you have to wait four weeks for these blockbusters.