As you know, we here at MPorcius Fiction Log are reading stories that Judith Merril included on a list at the end of 1959's SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction And Fantasy: 4th Annual Volume headed "Honorable Mentions." These stories, which were published in 1958, are listed alphabetically by author, and today we are finishing up the "C"s, though one of those "C"s turns out out be an "M" travelling incognito.

"The Last Day" by Helen McCoy (as by "Helen Clarkson")

Helen McCoy was a successful mystery writer who published this SF story under a pen name in the same issue of

Satellite that hosted the original version of

Murray Leinster's War with the Gizmos, which itself appeared under a different name, "The Strange Invasion." "The Last Day" would be reprinted in 1994 in

New Eves: Science Fiction About the Extraordinary Women of Today and Tomorrow; when that anthology was republished in a shortened version in 2010, "The Last Day" was one of the survivors. (There must be some kind of story behind this shortened edition, as the first edition has three credited editors but only one of those people is listed on the short edition.) It looks like "The Last Day" was expanded into a novel of the same name printed in 1959; a lot of expansion must have been required, as this thing is only five pages here in

Satellite, and those five pages are more than sufficient.

"The Last Day" is like a mainstream story, with lots of descriptions of the wind and the clouds and birds and flowers, as well as several Biblical references. (Merril is always working to blur the distinctions between mainstream and genre literature, and/or point out how arbitrary those boundaries are.) The narrator is a woman in some coastal New England fishing town. Near the town is a hollow which, by some freak of geography, is never windy. A nuclear war breaks out, apparently destroying civilization, but this somewhat secluded town survives the initial cataclysm. Of course the story doesn't blame the war on the Soviet Union, but on all of mankind, the way sophisticated people don't condemn burglars and muggers for their trespasses, but blame "society." The people of the little town gradually die of radiation poisoning; the local animals precede them. The narrator is the last to die, and before she expires she visits the windless hollow, where a bird has survived because the windborne radiation has not reached it yet.

This feels like the kind of story you are supposed to take seriously because of the subject matter, but the thing is bland and unremarkable. The characters don't do anything, nobody has any personality, and the author doesn't say anything new or interesting--she knows you know you are expected to like birds and flowers and dislike atomic bombs, and expects you to feel the appropriate sadness when she tells you the atomic bombs have killed all the birds and the flowers. "The Last Day" comes off as pretentious, lazy and obvious.

Thumbs down.

"Remembrance and Reflection" by Mark Clifton

Last year, based on Merril's recommendation, I read

Clifton's "Clerical Error" and liked it, and of course Barry Malzberg, our hero, is always telling people that Clifton is awesome, so we have reason to hope we'll like "Remembrance and Reflection."

isfdb tells us that "Remembrance and Reflection" is the fourth in a series, and this story is indeed full of references to and summaries of the earlier three stories; probably I should have skipped this one with the idea of perhaps reading all these stories in order some day, as my ignorance of the earlier installments almost certainly diminishes my appreciation of this one; e. g., in this piece, two characters from the earlier stories declare their intention to wed, and I had little idea if I should be happy for them or surprised or take their relationship as a joke or predict it would fail or whatever.

Ralph Kennedy is the personnel director at some manufacturing company that sells electronic to the government. The first few pages of the story are a jocular dialogue between Ralphie boy and his secretary that set the story's tone and expose us to its pro-risk, anti-overregulation ethos. Government and big business are too bureaucratic and, by over-emphasizing safety and discipline, stifle the creativity of employees and the development of new ideas. Ralph is the kind of guy who likes to bend the rules, to think outside the box. It seems that his adventurous and skillful management of employees who have psychic powers has, in those three previous stories, led to the development of an anti-grav device as well as joining the minds of five different guys into a collective consciousness; this collective has proven be be a singularly efficient manager of production, empowering the firm to increase output without lowering quality or harming worker morale.

The plot of this story involves a Colonel Logart of the Pentagon. He swings by the factory and tries to hire the psykers essential to Ralph's successes at the company away from the firm and into direct government employment on a big new project. There is a lot of verbal sparring between Logart and Ralph, who is our narrator, that features Ralph's analysis of the colonel's psychology and of the colonel's strategies in trying to manipulate Ralph and Ralph's colleagues. When Logart has no luck stealing the psykers away, the Pentagon decides that instead of the government directly running the project, the taxpayers will hire Ralph's company to take on the critical operation. This major public work is the design, construction and launch of Earth's first manned spacecraft, a feat the Pentagon feels can only succeed if the ship is propelled by those anti-grav devices only Ralph's psykers can build and crewed by those five guys who share a collective consciousness. To keep the project on track, Logart resigns his commission and becomes a project manager at Ralph's firm.

The third part of the story covers the space ship project, how Logart and Ralph get the whole thing up and running. The twist ending, of which Clifton provides plenty of foreshadowing throughout the story, is that Logart himself is a psyker whose mental powers make it easy for him to manipulate people--that is how he got the Pentagon, Congress, Ralph and Ralph's colleagues to sign on to the costly spaceship scheme--and that Logart never had any intention of leaving the space ship under the control of the United States government. Logart and the various psychics steal the ship and, bringing their wives along with them, escape off into space to start a new society somewhere out there.

While "Remembrance and Reflection" is heavy on exposition and philosophical discussion, I still kind of like it. The philosophical stuff is interesting and I am more or less in sympathy with Clifton's apparent ideology--besides the skepticism of government and the stuff about too much regulation and an obsession with safety stifling innovation, there is also talk of how liberal societies like the United States, under the pressure of conflict with tyrannical societies like the Soviet Union, run the risk of coming to resemble those societies, plus a pervasive theme of how the thinking of individuals is severely circumscribed by their education, by the milieu in which they were brought up (their "framework") and it is difficult for a person to understand people whose minds inhabit a different "framework." The parts of the story actually dealing with the things Logart and Ralph have to do to get the space ship built are entertaining and illustrate this "framework" theme. I also like that Ralph, whom we readers expect to be the hero, and is an outside the box thinker who is supposedly an expert in understanding and managing people, is outwitted by Logart, who is even an even more independent, framework-busting thinker and even better at figuring people out and controlling them.

Not bad. "Remembrance and Reflection," along with the earlier Ralph Kennedy short stories, would be reprinted in a 1980 Clifton collection edited by our beloved Barry Malzberg and workaholic anthologist Martin H. Greenberg as well as a Clifton collection printed forty years later in 2020.

"The Day of the Green Velvet Cloak" by Mildred Clingerman

We often say that SF stories are wish fulfillment fantasies--we just said it about Raymond F. Jones'

"The Gardener," in which a shy nerd not only makes friends with a big-man-on-campus jock but then learns he is a member of a superior race and his fellow supermen are always there watching over him. Today we are saying that "The Day of the Green Velvet Cloak" is a wish fulfillment fantasy not for friendless nerds, but for women--in Mildred Clingerman's story a woman succeeds in love and in life because she smokes cigarettes and spent her savings on fancy clothes.

Mavis O'Hanlon has been engaged to bank owner Hubert Lotzenheiser for six years. Mavis isn't crazy about Hubert, who is always trying to get her to stop smoking and to teach her self-discipline--Mavis is "chicken-hearted" and Hubert thinks she needs "fibering up." Ironically, the reason Mavis is still engaged to Hubert is because she is timid--if she was brave she would call off the engagement.

A week before the wedding Mavis blows most of her savings on the purchase of an expensive green cloak of Victorian style that she admits to herself she is too shy to wear in public. Then she looks for her favorite used bookstore. Mavis loves late nineteenth-century travelogues and journals written by women--she thinks the late Victorian period was a happier time than today, when everybody is in a hurry and expected to work hard; Mavis thinks that she would fit in better in the 1860s or 1870s, that back then "there was room enough in the world for all kinds of people--the inefficient, the chicken-hearted...." (I'm not sure if Clingerman believes this herself, or is just providing further evidence that Mavis is a person who has some faults.) Mavis' favorite bookstore is a little place that she sometimes can't find, and, when she does find it, seems to have a different clerk behind the counter every time she visits.

Today she finds the store, and on the shelves the journal of an American woman describing her travels with friends in Germany in 1877. When the clerk sees the book he has an amazing story to tell--he was travelling with the journal writer on the very trip described in the book when he looked into a German bookstore and was transported to this 20th-century American bookstore while reading a book of fiction about the future! He has been stuck here in this little store for three days, and is getting cold and hungry, as he has no money and finds the city beyond the bookstore's front door terrifying. He thinks that maybe he can return to his own time by reading this journal Mavis has found, in which he himself is mentioned.

The 19th-century man is grateful when Mavis gives him her new green cloak to wear in hopes it will warm him up. Furthermore, when he sees Mavis whip out her cigs and start puffing away, he is astounded by her bravery. She must be one of the bold "New Women" he reads about in those stories of the future of which he is so fond! Her even suggests Mavis come back to the 19th century with him and marry him. Mavis refuses, and runs off to get some food for the time traveler, but when she returns he, and her green cloak, are gone.

This adventure has fibered her up, and she plans to dump Hubert. But before she can do so, a man who looks like the time traveller shows up at her place. He says he is that Victorian guy's great-grandson, and in his great-grandfather's will were instructions to find Mavis and meet her on this date and give her back the green cloak. Mavis and this guy run off to get married without even telling Hubert. (I think the kids would call this "ghosting.")

Now, maybe you aren't so sure the late Victorian era was a paradise for women compared to the middle of the 20th century, and perhaps you even doubt that smoking cigarettes and throwing your money around recklessly is a capital idea. Still, "The Day of the Green Velvet Cloak" is a pretty well-constructed and well-written filler story. Maybe 2024 SF readers will love it for having a female protagonist, or maybe they will condemn it because it portrays a woman whose primary goals in life are bagging a husband and spending money. Either way, this story is a bazillion times better than McCoy's "The Last Day," because the characters have personalities and the protagonist makes decisions and overcomes obstacles and changes as a person.

In the 1950s and '60s, "The Day of the Green Velvet Cloak" would be reprinted in European editions of F&SF and Venture, F&SF's sister publication, as well as in the Clingerman collection A Cupful of Space, which has a sort of scary Powers cover. (This story is a sort of light entertainment, but maybe other stories in the book are disturbing?) In the 21st century "The Day of the Green Velvet Cloak" would reappear in the Hank Davis anthology As Time Goes By and a big (and apparently comprehensive) Clingerman collection, The Clingerman Files.

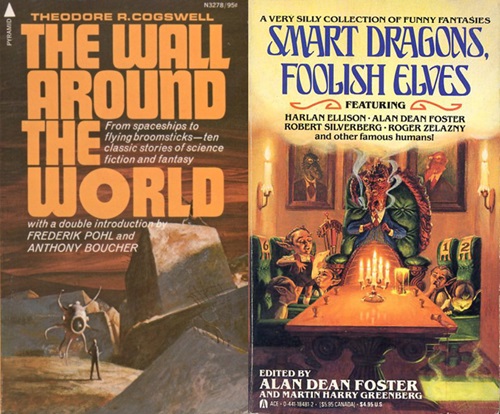

"Thimgs" by Theodore R. Cogswell

Uh oh. As I've told you many times, I generally avoid absurdist and satirical stories, and it looks like the only time "Thimgs" has been anthologized in English is in the Alan Dean Foster and Martin H. Greenberg volume

Smart Dragons, Foolish Elves, which is promoted as "A Very Silly Collection of Funny Fantasies." Well, we're trying this one on for size anyway...after all, it is only like ten pages.

The story stars a fat jerk, Blotz, who runs a fraudulent mail-order private eye business. People hire him to help them find lost family members or whatever, and he takes their money and claims to be doing the investigating for which he has been paid, when really he is just sitting around his office listening to horror stories on the radio and drinking heavily. To handle the correspondence he has as a secretary a woman who is crippled by numerous birth defects.

In a sort of meta SF joke about the often-seen trope in fiction of an odd little shop that disappears (like the book shops in the Clingerman story we just read), a radio program about just such a shop inspires Blotz to send his hunchbacked near-sighted secretary out on her crutches to buy something at a curio shop to send to one of his clients. She comes back with an odd little doodad with a knob. When the secretary twists the knob she vanishes but soon returns, transformed into a beautiful, healthy woman!

Blotz starts groping the secretary and she pushes him away. He starts to have a heart attack and grabs the thingmajig and turns the knob, and is transported to a room full of computers and recording devices manned (or staffed, you know, in feminist) by a mad scientist type guy. This guy implies that his facility is one component of the secret control apparatus of the universe that does what, in conventional conceptions of religion, God does, judge people upon death and reward the good and punish the wicked, for example. This guy's name is "Guardian" and his specific job is to record people's lives on tapes, or I guess to run the tapes, since it seems like people's lives are predetermined and already on the tapes--whatever; Cogswell's story doesn't make a lot of internal sense. The gizmo the secretary found is a key that allows a mortal to request edits to the rest of his or her tape. The secretary had hers edited to make her body healthy.

Blotz wants his tape edited so he is rich and healthy and good looking. The Guardian says that doing so would be pointless as only the future can be edited, not the past, and Blotz's fatal heart attack has already begun and he only has like 90 seconds of future ahead of him. Blotz somehow convinces the Guardian to start splicing the Blotz tape onto other tapes, so he can continue living indefinitely, and to make sure all of the tapes spliced onto his life be those of rich men. But the joke is on Blotz, because the Guardian keeps splicing onto Botz's tape brief lengths of tape from the final terrifying and/or painful moments of men of wealth who got killed in fights, accidents, etc.

"Thimgs" is contrived and nonsensical, and is neither funny nor interesting. Thumbs down!

If you want to read this clunker yourself (it seems that Anthony Boucher, Judith Merril, and Fred Pohl like it, and I can't think of any reason why you should listen to me instead of them) you can find it in the 1962 Cogswell collection The Wall Around the World, which has a "double introduction" from Messrs. Boucher and Pohl. I suggest getting the 1974 edition, which has an awesome cover painting by John Schoenherr that was also used for multiple editions of Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night.

**********

It is easy to find fault with the Clifton and Clingerman stories, but they more or less succeed in what they are trying to accomplish and I don't feel like I wasted my time reading them. I certainly feel I wasted my time with McCloy's lame effort at a tearjerker and Cogswell's wacky fat-fraud-goes-to-hell joke story, but I have to acknowledge that my main objection to them is to their authors' chosen goals--maybe people who crack open SF magazines looking for maudlin misanthropic stories about how humanity has doomed the flowers and birdies and madcap absurdist parodies of genre literature will think that McCloy and Cogswell have hit the nail on the head.

When next we meet, more 1950s SF.