'I'm appealing to you.' Kitty had got into her stride by now. 'It's all I can do. I've nothing to fight with, no bribe to offer. I can only ask you to realize the unhappiness you'll be bringing four people who've never hurt you.'

'Which are they?'

'Roy's two children, our own child, and myself.'

'You aren't including him, then.'

'That's not for me to say.'

'No, that's right. Well, from the way he talks about his life at home, I can't see he gives a sod for any of you, so I don't see why I should.'

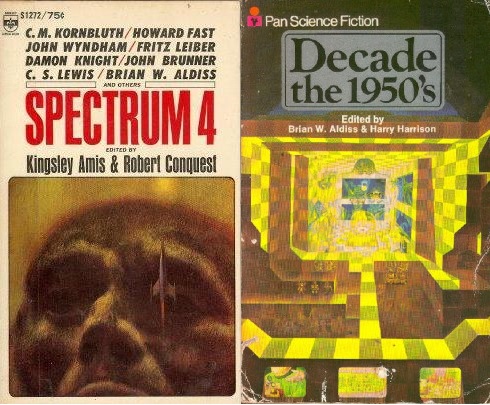

Let's check out another novel by Kingsley Amis, this one Girl, 20, first published in 1971, the year of my birth. I have a 1973 Bantam paperback which a previous owner contrived to keep in one piece with packing tape; a good job, too, as the book is still intact even after a week of bouncing around in my shoulder bag as I walked hither and yon in our nation's capital and in the back seat of the Toyota Corolla as I drove up and down the East Coast.

Smart people love classical music and know all about it, and lament its decline (we just read a story by Barry N. Malzberg that is like a sad love letter to classical music.) So I guess we shouldn't be surprised that the narrator of Girl, 20 is a newspaper critic who writes about classical music and expresses contempt for pop music and jazz. This guy, Douglas Yandell, 33, for some time in the past served as secretary to prominent conductor and composer Sir Roy Vandervane, a man in his fifties, and they are still pals. Both unmarried Douglas, and Roy, who is on his second wife, Kitty, and is father to a twenty-something son, Christopher, a daughter of 20, Penny, and a son of six, Ashley, are womanizers. Roy regularly cheats on his wife, going from one young woman to the next, and he does a quite poor job of concealing these affairs.

Girl, 20 is full of politics, starting from page 1. Douglas tells people he has no interest in politics, but the people around him are obsessed with the topic. The editor of his newspaper, Harold Meers, is a hardcore anti-communist who doesn't want Douglas to write an article about a talented East German pianist because he fears it will serve as propaganda for the tyrannical GDR. Among those living at the Vandervane estate is a West Indian, Gilbert Alexander, a writer who is, somewhat informally, a kind of tutor for Ashley, chauffer for Roy and Kitty, and boyfriend (or maybe just sex partner) to Penny. Gilbert calls every white person he meets a racist fascist imperialist and complains about white supremacy. Wealthy Roy (Kitty says to the narrator, "'You know, Douglas, it's quite frightening how much Roy earns now,'") is a socialist who has adorned his rooms with pictures of Che Guevara and a bust of Mao Zedong. Amis suggests that both Gilbert and Roy's politics are merely performative, what we today might call "virtue signaling." In one scene Roy jumps to help a blind man cross the street, only to be disappointed, even angered, upon learning the man is not blind at all, but simply wearing dark glasses. Signaling his separation from true working-class people, we get a scene in which a bus driver who recognizes the famous Roy tells the composer to move to Russia if he thinks England is so bad.

|

| Squint or click to read enthusiastic blurbs from my copy |

The plot. Roy is having an affair with 17-year-old Sylvia, a girl whom, when Douglas meets her, is stoned and acts in an outrageously cruel and callous manner. Roy is attracted to Sylvia for her youth; as a leftist he is simpatico with the rebellious youth culture of drugs and rock music (he tells pop-music hater Douglas not to judge rock music on the basis of acts like Herman's Hermits, but rather good bands like Led Zeppelin) and the thing that sexually arouses him nowadays is the breaking of laws and the defying of social mores--he's been with many women over the years and he is no longer aroused by prosaic sex, but needs a little depravity to get turned on. Amis/Douglas gives us multiple clues that suggest that Roy is attracted to Sylvia because she looks like his daughter Penny. (Gross!)

Sylvia is no longer content with getting banged in private--she wants to go out in public with her famous lover. Roy has the idea that he and Sylvia can go out on the town if they bring Penny with them, camouflaging their affair behind the story that Sylvia is Penny's friend and just tagging along. (In fact, Penny has never met Sylvia.) Roy figures that this cover story will be buttressed if Douglas accompanies them in the role of Penny's boyfriend. Douglas resists, but Penny, whom he finds attractive (she has very high and firm breasts) implores him and he agrees, setting the stage for the uncomfortable evening out during which Sylvia, who acts like an absolute jerk, and Penny meet.

Roy isn't the only member of the Vandervane household to ask Douglas for a favor. When it looks like Roy is actually going to leave Kitty for Sylvia, Kitty and Penny each independently beg Douglas to try to convince Roy to break things off with the teenaged girl and save the Vandervane family from total destruction. When this doesn't work, Douglas accompanies Kitty when she goes to Sylvia's flat to beg the girl to show mercy on Roy's family, a confrontation that goes disastrously.In the Sylvia-Kitty confrontation scene, and a scene in which Roy explains his behavior to Douglas, Amis illustrates in broad strokes his theory that socialists and other rebels against society are not principled ideologues who are fighting for a better world but selfish libertines who have absolutely no concern for others. Roy admits that everything he is doing--like cheating on his wife and championing the fashionable causes of the young--is in the shallow pursuit of pleasure. He composes music for rock musicians and goes on TV to argue in favor of left-wing causes because it makes teenaged and 20-something girls want to have sex with him and boys of that age admire him, and he enjoys being the object of attention he compares to "hero-worship." Seeing that Roy doesn't care about his family, Douglas takes a different tack, arguing that by immersing himself in pop music, leftist politics and sexual license--mere ephemera!--Roy is failing to live up to his potential as a musician, is sacrificing his opportunity to truly make the world a better place by contributing to the eternal project that is high culture. Roy is not convinced, and Douglas turns to more desperate measures still, measures quite underhanded!

Gilbert also has a favor to ask Douglas; Gilbert is fond of Penny and sees how living in her collapsing home is hurting her, and asks Douglas to help him convince Penny to move out of the Vandervane estate and and run away with him (Gilbert.) We readers have to wonder about Gilbert's feelings about Penny, however, when Gilbert offers to Douglas as an inducement the opportunity to have sex with Penny!

In the final quarter of the novel Roy and Sylvia's relationship comes under assault from another direction. Sylvia, in one of those it's-a-small-world coincidences fiction is replete with, turns out to be the daughter of the editor of Douglas' paper, right-winger Harold Meers! Meers has been doing research on Roy, and has interviewed Roy's son Christopher, and threatens to publish the interview, in which Christopher brutally attacks his father, if Roy doesn't leave Sylvia.

In the final fifth or so of the 245-page novel, we get various climactic scenes. Douglas meets the father of a woman he sleeps with on the regular, Vivienne Copes--Mr. Copes is a religious man who reads science fiction and suspects the moral character of the British people is in such dire straits that the United Kingdom would benefit from dictatorial rule. Also, the best thing that could happen to the people of Africa is if the British conquered and administered the dark continent again. This character is, on the one hand, a goofball, but on the other, his commitment to the world around him, and the world that Christians and SF fans feel must be beyond this one, casts into relief how shallow is Douglas, how our narrator is a man who only cares about music and sex, a man who is not interested in building a family or preparing for the future.

Roy, on violin, accompanies a rock band on stage in their performance of a pop song of his own composition; the crowd does not appreciate the performance and on their way out of the venue Roy and Douglas are assaulted by thugs and Roy's Stradivarius is destroyed. But Roy remains committed to pop music and youth rebellion, and to marrying Sylvia, outwitting Sylvia's father and rebuffing Douglas' efforts.At the end of the story we find that all of Douglas's efforts to accomplish anything have been met with failure. He couldn't stop Roy from leaving his family. He couldn't stop Roy from wrecking his career in serious music. Douglas gets fired from his job at the newspaper, and Vivienne ends their casual sex relationship. But Amis makes clear that Douglas' sin is not that he gets defeated every time he launches an enterprise--his sin is not launching enough enterprises, not engaging enough in life. Vivienne is cutting Douglas off because she is getting engaged to Gilbert Alexander--where the cool Douglas was content with a mere physical relationship, because he didn't care deeply about Vivienne and had imbibed the current feminist thinking about how men and women are equals, Gilbert has fallen in love with Vivienne the person, and, as a West Indian, has older ideas about sexual relations, and has been acting like a "masterful man" with Vivienne. Gilbert's telling her what clothes and jewelry to wear (when Douglas didn't care that she had bad taste and looked sloppy), for example, Vivienne interprets as evidence Gilbert truly cares about her--Douglas' open-minded, laissez-faire attitude she sees as proof he doesn't really care about her.

The final scene leaves things up in the air for Douglas and Penny. Penny, shattered by the collapse of her family, has, it appears, turned to heroin! Douglas is attracted to her, and in theory he could follow Gilbert's example and take up the role of the masterful man and take Penny in hand, save her from the doom that is addiction to H and with her build a worthwhile life based on traditional gender roles, but does he care enough about her to do so? The ironic final words of the novel are "We're all free now," Amis suggesting that the freedom brought by the sexual revolution and society's embrace of drugs is a trap, that this kind of freedom leads to destruction and a kind of slavery, that true freedom can only thrive within the guard rails of traditional rules and hierarchies.

Girl, 20 is a competent mainstream novel. Many of its ideas--e.g., that socialists are generally selfish hypocritical jerks and people who have lots of sex get jaded and lose the ability to get aroused by conventional sex and so pursue increasingly bizarre fetishistic sex--are ideas I basically agree with, and the others--e.g., that the liberations associated with the 1960s have made life worse rather than better--I find intriguing if not wholly convincing. However, these are all ideas I have been exposed to many many times; from my perspective these ideas are conventional wisdom rather than new and exciting revelations. The novel's jokes--for example, Douglas is tall and hits his head on things--are not bad, but only once did I literally laugh. Amis' characters are believable, but I didn't find them terribly sympathetic or engaging, while Amis' tone is sort of understated, putting emotional distance between the reader and what is going on.

One of the appealing things about the novel--and other of Amis' novels I have read--is that he is obviously interested in things I am interested in, like science fiction (and genre fiction in general) and military history--Douglas refers to Dracula and Frankenstein and many of the book's little jokes involve martial metaphors and references. Hinting at how Roy and Kitty's lackadaisical parenting style has turned little Ashley into a hellion, we get this exchange between Kitty and our hero:

'We've got a new system [of persuading Ashley to attend school.] Every day he goes, he gets a surprise when he comes home.'

'What sort of surprise?'

'Something nice, of course. Something it's fun for him to play with.'

'You mean like a trench mortar or a flame-thrower or a--'

'There are no militaristic toys in this house, Douglas.'

This dialogue also makes one of Amis' points, that left-wingers misdiagnose the world's problems and make them worse with their misguided prescriptions--Roy and Kitty simplemindedly think that it is playing with toy soldiers that makes people violent, while actually doing the very thing that is in fact turning their kid into a troublemaker--depriving him of discipline.

(One of the minor themes of Girl, 20 is how children and parents disappoint each other--in the novel the conservative or right-wing parents have kids who are sluts while the offspring of left-wing parents turn on their progenitors, denouncing their indulgent and self-indulgent ways or actually engaging in physical violence. At the end of the book, however, it does look like Mr. Copes, the most right-wing of the parents, may live to see his daughter in a stable healthy marriage.)Girl, 20 is a success--the book is well-paced and well-structured and all that, and Amis appears to accomplish his goals--so I guess on a technical level it is good, but its ordinary plot and ordinary point of view did not thrill me or challenge me. Like a guy who has banged so many chicks he has to break the law to get aroused, it seems like I have read so much fiction I can only get really excited by a story if there are monsters or aliens or space ships or sorceries in it. I guess I can give a mild recommendation to Girl, 20, and a stronger rec to feminists and BLM activists who are looking to fuel their rage.

.jpg)