At the Dupont Circle location of Second Story Books, on the clearance carts, I recently spotted a volume entitled

Speaking of Science Fiction, a collection of interviews of SF writers and editors conducted during the 1970s via the mail mail by Paul Walker. I was interested in the book, but I am incredibly cheap and so instead of buying it I found the scan of it at the internet archive and flipped through it while riding the subway (which in D.C. they call the Metro--oh la la!)

One Paul Walker's interviewees is Damon Knight, and one of the main topics of the interview is Knight's famous series of anthologies of original stories, Orbit. (Knight also does his husbandly duty, gushing praise for his second wife Kate Wilhelm, talks up the Clarion workshop, and admits that his famous attack on A. E. van Vogt in In Search of Wonder was one-sided and he wishes he had "included something about vV's strong points.") Orbit, Knight writes, "represents an attempt to bring about a renaissance in science fiction by demanding high standards and giving a lot in return--high rates, prompt reports, courteous treatment, etc." He says that improving the quality of SF requires "redefining the field" and "letting go of rigid conceptions of what science fiction is;" he argues that "booms for quality" in the past have been the product of editors who have done just that, citing "Tremaine in the mid-thirties, Campbell from '37 to '42," and "Gold and Boucher in the early 50's." With Orbit, Knight claims, he is not "editing to strict ideas of subject and content," but is "keeping the boundaries fluid" and publishing lots of work on the "fringe of science fiction" or even beyond it that surprise him. At the same time, and perhaps most interestingly, he asserts that "Orbit has never had anything to do with the stylistic experimentation of the New Worlds/New Wave scene." I am often struck by how nobody can agree on what the New Wave is or what it was all about.

|

The listing of "Gene Wolf" on the cover of the paperback edition is a mistake;

Gary K. Wolf appears in the anthology, not Gene Wolfe. The promise of

editorial notes and personal commentary also seems to be a mistake--

at least there is no such additional matter in the scan at isfdb, just two pages of

jokey biographies at the end of the book; in his interview with Walker,

Knight discusses why he stopped composing intros and "blurbs" for Orbit. |

Reading this interview has made me want to read some Orbit stories, so I again turn to the internet archive, this time to take a look at Orbit 13 (lucky!) from 1974. Here at MPorcius Fiction Log we recognize all too well that life is short, and so we won't be reading all 240 pages of Orbit 13, just cherry-picking stories by writers we already have a particular interest in. I guess this goes against Knight's whole open-minded, innovation-privileging, no-set-ideas, aim-to-push-the-boundaries mindset, but that's how it is.

"And Name My Name" by R. A. Lafferty

We start off with a story the superiority of which was endorsed by another important SF editor; after its debut here in

Orbit 13, "And Name My Name" was selected by Lester del Rey for inclusion in the 1975 edition of his

Best Science Fiction Stories of the Year series. The tale has since appeared in Lafferty collections.

"And Name my Name" posits a bizarre secret history of the world in which the Earth has been successively ruled by different classes or orders of animals: elephants, sharks, whales, crocodilians, etc. In their time of primacy the ruling beasts have speech, art, even wear clothes, but when they are supplanted by the next rulers, lose these abilities and attributes and become dumb animals. All except a small elite of seven or nine of their number, immortal representatives of their order at its height. As the story (15 pages) begins, the seven elite apes, drawn from all across the world, are travelling to a conclave of all the sophisticated elites representing all the past rulers, because the times they are a-changing. After we have been introduced to the ape delegation, we encounter the seven elite individuals who represent the current rulers of Earth, the human race. At the big meeting in Mesopotamia a shining man appears; able to bend space and time he treats with each delegation separately but also simultaneously. He assigns all the different species their roles in the new age, a process referred to as "telling them their names," and the members of the human delegation are pretty discomfited to learn they have no real name beyond "secondary ape" and to hear their culture of towering cities, nuclear reactors and space ships, dismissed out of hand by the shining man, judged less admirable than the hives of termites or the song of the mockingbird. What will replace the human race that is about to be reduced to dumb animals as its civilization is swept away ,is left to the reader's imagination, but all the non-human characters seem sure it will be an improvement on humanity!

This is a good, fun story, and I think it fulfills Knight's ambitions for Orbit--it is innovative, throwing a new and crazy idea at you, and it is on the fringes of standard definitions of science fiction, seeing as it totally ignores all accepted science around biology and paleontology and all that and replaces it not with speculative science but what is a sort of religious view or just a fairy tale that casts the human race as inferior to the birds and the bees. At the same time, the story is in direct dialogue with quintessential mainstream SF, as some of the human characters refer to Arthur C. Clarke stories by name.

Good on Lafferty for producing a good story and good on Knight for publishing it. Thumbs up!

"Going West" by Edward Bryant

Looking at the records, it seems that 15 stories by Edward Bryant have been subjected to the sometimes pitiless, generally myopic and always erratic MPorcius microscope, plus the novel Bryant coauthored with bad boy Harlan Ellison, Phoenix Without Ashes, which you might call a piece of shrapnel or a submunition thrown off by one of Ellison's many explosive collisions with Hollywood. While there are some clunkers among those fifteen, Bryant is a serious writer and his stories are generally thoughtful and ambitious (for one thing he seems to write a lot about various "marginalized communities," e. g., women, blacks, Hispanics, and homosexuals, which is sort of risky and interesting), and they are often effective, so we have reason to hope "Going West" will be a good story.

"Going West" is indeed a good psychological horror/crime story, a character study and biography of a guy whose unhappy life drives him to trespass against the law and others; I guess you could call "Going West" an attack on our society, argue it suggests that American foreign policy and American racism created a monster out of the main character and that all the empty highways and congested interchanges in the story represent the loneliness and chaos of our individualistic culture of strivers and our complex capitalist economy. (The title itself is a clue that the story is about America writ large, "going west" being a sort of quintessential theme of American history.)

Lindsey was raised on the East coast by a single mother, his father having been killed in Cambodia. Mom was cold and distant, and little Lindsey didn't make friends and was pretty maladjusted. For example, he came to adore the school buses, to think of them as living animals, and was traumatized when activists angry about busing blew up one of the buses while it sat in a parking lot.

In college Lindsey's bicycle was repeatedly vandalized and eventually stolen. After graduation, Mom got Lindsey a job at an accounting firm, owned by a Lindsay and his son. The fourth man at Lindsay, Lindsay, Lindsey and Veach was an aggressive homosexual who kept irritating shy and sad Lindsey, flirting with him and advising him to see a shrink he knew who was a "pussycat."

Lindsey started having some kind of breakdown, which the senior Lindsay recognized, so he gave Lindsey some time off, and Lindsey is now driving to Los Angeles with no fixed reason to do so in mind, other than to get away from home, where he assaulted the doctor recommended by Veach. As he drives he becomes progressively more insane, and we readers are privy to what appear to be hallucinations as well as memories, each of which may or may not be false, of people and of conversations--we cannot be sure that anything Lindsey sees or hears or remembers is real. There are also allusions to Lewis Carroll's Alice. In the story's climax it seems Lindsey dies after driving off a highway overpass, victim of his hallucinations or a death trap in a through-the-looking-glass universe of murderous highways.

As I have told you a hundred times I miss living in New York City and one of the things I miss is never having to drive--I hate driving and all the attendant risks and responsibilities, worrying about the car's tires and oil and fuel and all that. Because I am from New Jersey and my wife is from the Middle West and has family who have fled the Northern winters for the balmy South I find myself on many long road trips, driving hundreds and hundreds of miles up and down the East coast and back and forth between Washington D.C. and the rural Heartland. So, I found Bryant's descriptions of the experience of driving for hours and hours and then trying to navigate a complicated series of junctions quite compelling. The horror stuff in "Going West" is suitably sad and disgusting, and while the story is something of a puzzle, told out of chronological order and full of surreal sections, it is not hard to figure out.

So, thumbs up for "Going West." As a psychological horror story it is certainly on the fringes of, or even outside, conventional definitions of science fiction, though maybe the magical realist ending qualifies it as "SF." According to isfdb, "Going West" has never been reprinted; too bad.

*"Sending the Very Best," "The Soft Blue Rabbit Story," "Shark," "Pinup," "Road to Cinnabar," "Audition: Soon to Be a Major Production," "Strata," "Dancing Chickens," "Cowboys, Indians," "Nova Morning," "Beside Still Waters," "In the Silent World," "Dark Angel," "Jody After the War," and "Black Onyx"

"My Friend Zarathustra" by James Sallis

I've read eight or nine stories* by James Sallis over the course of this blog's tempestuous life and I have not liked many of them; in fact, I think I have denounced half of them as a waste of the reader's time. I am just reading this one because it is a mere three pages long and because I wanted to say that seeing the name "Zarathustra" in print always makes me think of Roxy Music's

"Mother of Pearl."This is one of those stories by a writer that is about being a writer, how hard it is, how you hang around with other mentally unstable creative people who cry and vomit all the time and sometimes commit suicide. It is vague. Some of it is written in the first person, some in the third person; some is in past tense, some in present tense. There are lots of images of stuff like the sunrise and neon signs. The plot, such as it is, is about how the narrator's girlfriend left him for a friend. The last paragraph seems to be evoking scenes of the torch-wielding villagers who come to the castle at the end of movies about Dr. Frankenstein, perhaps suggesting that writers, painters, musicians, etc., are like mad scientists who take risks, break the rules, and sacrifice others to bring about new life, new life that is sometimes twisted and destructive and arouses the enmity of the populace.

Pretentious goop that goes nowhere and is eminently forgettable. "My Friend Zarathustra" would reappear in Sallis's 1995 collection Limits of the Sensible World.

*"Field," "Tissue," "The First Few Kinds of Truth," "Delta Flight 481," "They Will Not Hush," "Faces and Hands," "Binaries" and "Only the Words are Different"

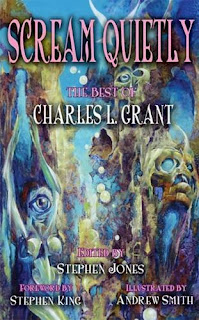

"Everybody a Winner, the Barker Cried" by Charles L. Grant

Charles L. Grant is the "quiet horror" guy. If isfdb is to be believed, "Everybody a Winner, the Barker Cried" has never been reprinted, so if you are a Grant completist, it is time for you to hit up ebay and drop two or three sawbucks for a copy of Orbit 13.

There was a nuclear war recently, and almost everybody is dead. A man and a woman meet at a seaside amusement park, both of these thin and haggard victims of radiation sickness who vomit all the time have independently come to the beach because they have happy memories of the place. "Everybody a Winner, the Barker Cried" chronicles the first few hours they spend together, during which they fall in love. As a college kid the man worked on the boardwalk, running a wheel of fortune, and says the line that serves as the story's title, and then remarks that the game is "fixed." I suppose we are expected to see this as symbolism that our lives are similarly rigged by the existence of nuclear weapons. The man is resourceful and has got generators running so the two can ride the decrepit ferris wheel. (Feminists will groan at how the man saves the woman when she gets in trouble, picks her up when she falls, cooks the food, fixes broken machinery, and is a total gentleman who doesn't molest the woman, while the woman mostly cries and worries about her looks and obviously needs a boyfriend more than any fish ever needed a bicycle.) Riding the ferris wheel offers these two ferris-wheel-lovers hallucinations of their happier days, and they decide to find a boat and sail to Coney Island to ride the much bigger ferris wheel there. The end of the story is sort of ambiguous, with notes of hope as well as the pervasive idea that they are likely to die at any moment of their radiation sickness.

Acceptable. This is more mainstream science fiction than some of our other Orbit 13 reads, consisting of speculation of how people will react if there is a nuclear war, though the focus is on nostalgia and sadness and a human relationship than rebuilding civilization or something like that.

"Black Sun" by Dennis Etchison

I've been impressed by many of the Etchison stories I have read, like

"Daughters of the Golden West," "It Only Comes Out at Night." and

"Wet Season"; at one point

I even had the idea of reading the entire Etchison collection Red Dreams, though that ended up not happening (yet.) So, I have hopes "Black Sun" will be good.

Well, the good news is that I am one step closer to reading all the stories in Red Dreams because "Black Sun" is included in that collection. Maybe we'll really accomplish that goal some day. The bad news is that this story is pretty opaque and boring. As far as I can tell, the narrator is in a legal fight to avoid the draft, and his wife is pregnant, sick and suicidal. There are lots of surreal scenes in which he deals with bureaucratic forms, his insane wife says crazy things, he looks at how skinny she has got, and wonders about the dots on her skin (it seems she is going to an acupuncturist instead of an obstetrician.) Both these characters are getting pretty rundown, and in the end of the story it appears the narrator is so changed that people don't recognize him anymore. He resolves to murder the acupuncturist and then take refuge in the wilderness, I guess an extreme reaction to losing his legal fight and/or the death of his wife.

An impressionistic mess; it takes some work to figure it out and what you end up with doesn't seem to justify the effort. I didn't really see the connections among the story's themes of draft-dodging, acupuncture, pregnancy and darkness (Vietnam is in Asia and acupuncture is from Asia? burning your draft card is associated with hippies and lefties and so is acupuncture?) The story is just a jumble of stuff and doesn't build to a climax or have any twists or turns, it is just a vague flat line from start to finish. One problem with the story may be that Etchison is relying too much on readers' passionate connection to current events to give the story energy, expecting people in 1974 to get all worked up over the issue of the draft and so neglecting to include more universal themes; will readers in 2074 get the charge out of a story the main theme of which is the provision of puberty blockers to minors or AFVs to Ukraine that today's readers might get?

I think I have to give "Black Sun" a marginal negative vote.

"Flash Point" by Gardner Dozois

Looks like another horror story--"Flash Point" would go on to be included by Charles L. Grant in his 1983 anthology

Fears and by Dennis Etchison in his 1986 anthology

Masters of Darkness. Were SF readers in 1975 disappointed by the high proportion of horror tales in

Orbit 13? Did Knight think that publishing horror stories in a science fiction anthology was somehow "innovative" or "redefining the field"? Well, in Knight's defense, "Flash Point" does consist of speculation about the near future, so is more like traditional SF than Bryant's "Going West" or Etchison's "Black Sun."

You can also find "Flash Point" in Noreen Doyle's 2008 Otherworldly Maine, and it is a good choice for Doyle's anthology, as much of its text is devoted to creating a strong sense of place, offering lots of descriptions of the sights and sounds and the flora and fauna of its wooded setting and portraits of its small town people and the main character's relationships with them. That main character is Jacobs, a guy who makes his living repairing appliances and doing handyman jobs; he is also a Vietnam veteran who was wounded in combat. (Like "Going West" and "Black Sun," "Flash Point" reminds you that communism is nothing to worry about and that the world's problems stem from the sick society of the United States. Maybe this is what Knight considered "innovative.")

Jacobs finds a deserted car on the road; Dozois's detailed description of the vehicle and its contents makes it clear to readers that we are dealing with a case of spontaneous combustion! Jacobs does not recognize this, however, apparently never having had a copy of that Reader's Digest volume Mysteries of the Unexplained that creeped me out as a kid. He contacts the cops (the sheriff is a violent brute and his subordinates are idiots) and then has lunch at the local diner where we meet the various town eccentrics and, from the town doctor, get a strong dose of one of the story's themes: abnormal psychology and psychosomatic illness, how the mind can powerfully affect the functioning of the body.

Dozois gives us a lot of verbiage about Jacobs's feelings, his changing state of mind after finding the abandoned car. He becomes subject to powerful, violent rages, savors the idea of harming the anti-communist at the diner, a stray dog, the raucous wealthy tourists ("gypsies") who recklessly pass his pickup on the road and harass him. Late in the story, with a reference to hologram TVs, Dozois makes clear something that has not been evident earlier, that this story is set in the near future; the "gypsies" are a reflection of how violent and cruel and even suicidal American society has become, their extended visits to rural Maine symbolizing how even remote areas are subject to the degradation of American society that started, or at least was most evident initially, in big cities. The climax of the story is the presentation of stark evidence that the sick culture of America at large has subsumed even this little Maine community, a rash of the spontaneous combustion events and even the discovery of a Satanic coven that practices human sacrifice!

"Flash Point" is well-written, but some will perhaps find disappointing the fact that it is a longish (22 pages) mood piece; the main character does very little, acting merely as a witness, and the plot consists not of the characters taking a journey or overcoming obstacles but instead of the author progressively revealing to us readers the extent to which American society is sick and is turning ordinary people into killers and suicides. I've already compared it to Grant and Etchison's stories, and a similarity we might see to "Going West" and "Black Sun" is how over-the-top, through-the-looking-glass and surreal the ending of "Flash Point" might seem to some--witches sacrificing babies and a multitude of people spontaneously combusting is pretty "out there" for a story so much of which is so realistic.

As I have said, Dozois's writing is quite good--he delivers sharp clear images of the character's environment and his mental state, and the pacing is good; I was always interested, the pretty extensive descriptions never becoming boring. So, thumbs up for "Flash Point."

**********

Living up to our stereotyped view of the 1970s, these are some pessimistic, apocalyptic stories. And I suppose living up to Knight's objectives with the Orbit series, none of them is straightforward and none offers rational scientific explanations for the events they depict--all of them present characters who are hallucinating or who have experiences that are inexplicable except as religious phenomena or suspension-of-disbelief defying symbolism. I like horror stories and as I always do, I have judged these stories today on how interesting, entertaining and well-crafted they are, not on how closely they adhere to some kind of platonic definition of "science fiction," but I think it is fair to wonder if Knight, in expanding the definition of "science fiction" so far, is perhaps rendering the term meaningless, or making its essential meaninglessness more obvious. It is easy to suspect terms like "New Wave" and "science fiction" lack any concrete definition and are mostly useful as marketing categories or shibboleths used by people to declare allegiance to (or express contempt for) an identity group or cultural phenomena.

More terror awaits us in the next episode of MPoricus Fiction Log. Stay tuned!