"The Black Stone" by Robert E. Howard

"Ubbo-Sathla" by Clark Ashton Smith

"Scarlet Dream" by C. L. Moore

"The Dreams in the Witch-House" by H. P. Lovecraft

"The Isle of the Sleeper" by Edmond Hamilton

"The Unspeakable Betrothal" by Robert Bloch

"Perchance to Dream" by Charles Beaumont

"A Dread of Red Hands" by Bram Stoker

"The Watcher in the Green Room" by Hugh B. Cave

"The Lady in Gray" by Donald Wandrei

"Lover When You're Near Me" by Richard Matheson

"The Depths" by Ramsey Campbell

Today we'll read three more stories from the collection, those tales plucked by Messrs. D, W and G from the oeuvres of Thomas Ligotti, Robert Aickman and Charles L. Grant.

Today we'll read three more stories from the collection, those tales plucked by Messrs. D, W and G from the oeuvres of Thomas Ligotti, Robert Aickman and Charles L. Grant.

"Dream of a Mannikin" by Thomas Ligotti (1983?)

This story has appeared in several books, sometimes as "Dream of a Manikin" and sometimes as "Dream of a Mannikin" and sometimes as "Dream of a Mannikin, or The Third Person." There is some confusion at isfdb over whether the story debuted in 1982 or 1983, but it looks to me like its first appearance was in the 1983 issue of the magazine Eldritch Tales. In 1989 Jessica Amanda Salmonson included the story in her anthology Tales by Moonlight II, which appears to be a collection of stories that first appeared in small press magazines; "Dream of a Manikin" was reprinted in the Ligotti collections Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Nightmare Factory.

I guess we sort of expect Ligotti stories to be a little challenging, to be the sort of story you have to figure out, and this is true of "Dream of a Mannikin," but it is not terribly difficult. The story takes the form of a long letter written by a psychiatrist to a fellow shrink, a woman with whom he is in love, and we learn more and more about his feelings for her and the nature of their relationship as the story progresses. The last paragraph of the letter is in italics and is apparently the female therapist's notes on or response to the man's letter.

The main topic of the letter is the visit of a young woman, Amy Locher, to the letter writer. Locher has had a terrible dream and is seeking treatment, and it turns out she was directed to the narrator by the woman he is in love with. Ligotti puts multiple layers between the story and the reader as he has the letter writer describe Locher's dream, which mostly consists of a second, inner dream, the dream of the patient's dream version of herself. In real life (ostensibly) Locher is a clerk or secretary at an industrial firm, but in her dream she works in a clothing store and dresses the mannikins (the spelling is perhaps significant--I'd spell the term for those figures in a store "mannequin.") The retail worker version of the patient has a dream herself in which she is attacked by the mannequins she dresses and turned into a mannequin herself--this dream within a dream includes classic dream elements, like being unable to move and unable to scream when in danger.

The woman shrink has some totally wacky theories about "otherworlds" and powerful beings who toy with lesser beings that may be subordinate "splinter" aspects of themselves, theories that the narrator feels are more metaphysical than scientific, and the male shrink in his letter accuses her of manipulating Locher, of hypnotically inducing her dream, in order to acquire evidence of her bizarre theories and to lay a trap for him. And an elaborate trap it is--it seems the narrator's secretary is an agent of the woman shrink.

In the second part of the letter the narrator describes his investigations that lead him closer to the nature of the trap the woman psychiatrist has laid for him, which he nevertheless falls into. It seems the female shrink has somehow gained the ability, through contact with other worlds or dimensions, to take control of people and turn them into mannikins (also described as dolls--allusively, the lady shrink apparently had a doll named Amy as a child, and the word "darling" is spelled "dolling" multiple times throughout the story in multiple contexts) and she has done this to Amy Lochner and it looks like the male shrink is in the process of becoming her next victim. Or maybe the female psychiatrist can imbue dolls--and/or people--with alien souls she snares from outer space--one of the themes of the story is ambiguity and confusion about identity and transformation of identity. Or perhaps the female shrink is a space monster and all the other characters--Locher, secretary and male psychiatrist--are aspects of her soul which she plays with to help pass the aeons.

This is a well-crafted story; the depiction of dreams feels totally believable, the images are strong, and every sentence feels significant, offering some clue to the plot or adding to the atmosphere. "Dream of a Mannikin" does require some patience and it will give your noggin a workout, though, so maybe it's not what everybody is going to think of as fun entertainment.

"Never Visit Venice" by Robert Aickman (1968)

Robert Aickman is another writer whose work I expect to strain the brain case. The title of "Never Visit Venice" made me wonder if I was in for allusions to Thomas Mann's famous "Death In Venice," which I have read a few times, and to Proust--Venice (Marcel's desire to go there and his eventual visit) is a recurring theme in Remembrance of Lost Time, and strange dreams, in which little Marcel has become an inanimate object or an abstract concept, are a prominent topic of the very first page of that monumental novel. And then came the epigraph that opens "Never Visit Venice," some lines from Celine, whose Death on the Installment Plan and Castle to Castle we read back in early 2022.

Fern is an Englishman, an office worker who is shy, unambitious, and not very social; he doesn't make as much money as he could because he doesn't see the point, and he doesn't make friends or achieve any success with women largely because other people interest him but little. He has a recurring dream about embracing a woman in a gondola in Venice, and eventually actually goes to Venice, where the dream comes true in a macabre and surreal fashion. As the story ends it seems that Fern, alone in the gondola with the skeleton of the woman who beckoned him into the little craft, will drift out to sea to be drowned; one of the last things he sees is a political slogan painted on a wall, I guess a quote or paraphrase from Mussolini, asserting it is better to live like a lion for an hour than to live a lifetime as an ass.

Though the sudden revelation in the end, when the woman Fern has just had sex with becomes or is revealed to be a skeleton, is like something out of Weird Tales or EC comics, most of the story resembles literary fiction. The first part is page after page of Fern in England that focus on his ambiguous and diffident attitude toward life and career and money, and most of the remainder is page after page of Fern in Venice, finding everything disappointing and sensing that Venice's glory days are long past, a fact none of the living people in Venice are to acknowledge--only the ghost woman in the gondola will voice this sad truth. The pervasive atmosphere of the story is of ambiguity and irony--early in the story we learn Fern is both proud and embarrassed that he is different than other people and doesn't really get along with them, and we are told early in the Venice part of the story that Fern's expectations of what he would find in Venice, based on what he has read and been told, are not realized, that in fact he finds the opposite of what he was told to expect. And there are many other instances of irony and ambiguity. One of the more striking examples is the camouflaged suggestion on the last page that Mussolini, whom we always see portrayed as a monster or a buffoon, had a better idea about how to live than does the inoffensive Fern, a strange notion that I guess the quote from Celine, the notorious Jew-hater and Nazi-sympathizer, that begins the story foreshadows.

But it could be that Aickman is not endorsing Mussolini and Celine. Perhaps Aickman's point is that people who put themselves out there, who embrace life with vigor, are often evil people, and that being forward and ambitious is dangerous and ultimately pointless (Mussolini and Celine are, of course, in the final equation, losers who get humiliated.) Consider that Fern tries to realize his dream of love in Venice only to have sex with a skeleton who tells him one should "Never visit Venice" (i.e., do not pursue your dreams) and then get killed, and that early in the story Aickman puts forward the idea that travel is pointless, suggesting, as would a skeptic of "globalism," that easy travel and communication have served to homogenize the world, turn a world of diverse cultures into one big monoculture, so that travel and communication are unprofitable, every place being now the same.

Though not a lot actually happens in the story, Aickman's style, as in good literary fiction, is smooth and engaging and carries you along so the story doesn't feel long at all, even though there is little or no narrative drive. Thought-provoking and worthwhile.

"Never Visit Venice" first appeared in the Aickman collection Sub Rosa, and was also included in the collection The Wine-Dark Sea.

"The Last and Dreadful Hour" by Charles L. Grant (1986)

"The Last and Dreadful Hour" is one of Grant's stories about the town of Oxrun, and debuted in the collection The Orchard. The Orchard has appeared in numerous editions, and looking over their covers I was amused to see that in one edition the Stephen King blurb reads "One of the premier horror writers of his or any generation," but on another cover the quote has been misleadingly edited into "The premier horror writer of his or any generation." Was King aware of this inexcusable chicanery?

Ligotti's "Dream of a Mannikin" is like 12 pages long, and Aickman's "Never Visit Venice" is some ten pages longer. Grant's "The Last and Dreadful Hour" is ten pages longer still, clocking in at 33 pages, a fact that made me groan after I had read the first of those thirty-three, which is wholly devoted to a description of the weather, complete with poetic repetition--while Ligotti and Aickman's stories felt like literary fiction, Grant's from square one felt like the work of a guy trying to be literary but succeeding only in wasting everybody's time.

The second page of "The Last and Dreadful Hour" is given over to describing in mind-numbing detail the movie theatre in Oxrun. The aforementioned weather--a ferocious storm--causes a power outage, and the theatre manager goes on the sound system--which, unlike the electric lights, is somehow still working--to apologize. We are then introduced to a passel of boring characters with boring backstories, and forced to read bland and verbose retailings of their every move--

...she straightened, rubbed a hand over the back of her neck, and waved him out to the aisle. He grinned and did as he was told, thanked her as she joined him, took her arm and pulled her down a pace while Seth and Davidson moved to carry the old man...

--as they discover an unconscious man in the darkened theater. It is bad enough that Grant wastes our time detailing these boring people's every gesture, but his sin is compounded by the fact that his descriptions don't even work. Toni the medical student is holding Ellery the depressed bookstore clerk's hand, and then she lets go of his hand, but then two lines later she is "pull[ing] him slowly up the aisle," as if she never let go of his hand. So not only are all these descriptions tedious and useless, they are confusing, and then angering when you realize you are looking back up the page to reread boring sentences in hopes of figuring out if some dope is holding another dope's hand, even though whether or not these dopes are holding hands is meaningless. It is possible these apparent mistakes are intentional, an effort to make the story "dream-like," but I am betting Grant and his editor just screwed up.

Some supernatural force locks all the doors and renders all the windows indestructible so the characters are all stuck in the candle-lit (and believe me, we hear like one thousand times about wax dripping off these damned candles) cinema, in which all the women flirt with Ellery and the local rich guy acts like a jerk. People start disappearing, and while Ellery and a woman (not Toni, who has disappeared) are away from the group looking for one of them, she strips naked and tries to seduce Ellery, and then turns into a medusa and then into a skeleton. Ellery faints, wakes up, finds everybody is gone. A third woman reappears and flirts with Ellery before joining him on another search. Another woman reappears to flirt with Ellery, and they search some more. (This story moves in sterile circles--phrases, images, and actions all get repeated while the plot goes absolutely nowhere.) The same sort of stuff keeps happening until the story finally ends with the awakening of the old man and the hint that this mind-bogglingly lame story that makes no sense and achieves nothing is all just the dream of that old man whom they found unconscious--or maybe it is the dream of sad Ellery himself. (Toni's out-of-left-field mention of the orchard way back at the start of the story that implies the orchard is a locus of black magic or demonic possession or something is forgotten--maybe "The Last and Dreadful Hour" is more like a chapter of an episodic novel than a short story that can really stand on its own.)

This story is very bad. The plot stinks, with no resolution or development and lots of loose ends. The style is horrible, a mixture of the pretentious and the just plain dumb. The characters' actions and dialogue make little sense, are just a series of non sequiturs; characters in genre fiction often act stupidly so that the plot will work, but this story is even worse because it doesn't even have a plot in which anything happens.

Grant has won a pile of awards but this story is garbage and I don't know why Dziemianowicz, Weinberg and Greenberg put it in their anthology; maybe they had run out of dream stories? I will now take Stephen King blurbs even less seriously, and shun stories by Grant assiduously.

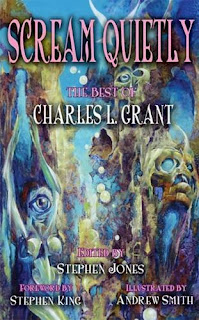

Incomprehensibly, "The Last and Dreadful Hour" would be included in the "Best of" Grant collection Scream Quietly.

**********

So today we have three stories that remind you that pursuing women is hazardous, two quite literary stories that are well-written followed by a piece of junk that makes you question the wisdom and honesty of Stephen King and the entire horror fiction establishment. What a ride!

It's been like six weird and horror blog posts in a row here at MPorcius Fiction Log; when next we meet we'll do something a little different.

No comments:

Post a Comment