"Wings of the Phoenix" by John Bernard Daley

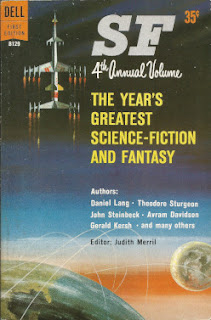

This guy Daley has three short fiction credits at isfdb and we've already read one of them, "The Man Who Liked Lions," an adventure story about warring Atlanteans that also serves as a denunciation of obese Americans. I don't actually seek out jeremiads against those of my countrymen who share my love of carbohydrates--I read "The Man Who Liked Lions" for the same reason I am reading "Wings of the Phoenix": because Merril recommended it. "Wings of the Phoenix" was only ever printed once, in Infinity, and even though Daley's story isn't mentioned on the cover, the cover illustration unmistakably depicts characters from "Wings of the Phoenix" and spoils a component of the ending."Wings of the Phoenix" is a postapocalyptic story that (I guess) is supposed to be funny. These are two more kinds of stories that I don't actually seek out but which I somehow end up reading pretty regularly.

C. Herbert Markel, III, is one of the very few survivors of the atomic war and the plague that followed it. Markel is a little mad, and has a messianic image of himself as the man who can sire and educate a new human race, one that won't start cataclysmic wars. To achieve his lofty goal, he first needs a woman to give birth to the first generation of the new race, and early in the story he finds a fat blonde woman (Daley reminds us again and again that this woman is fat) whom Markel dubs "Earth Mother," even though she informs him she already has a name--Darlene. Besides being fat, Earth Mother is ignorant, vapid and stupid, and her dialogue features grammatical errors, slang, and mispronunciations, and in large part consists of lamentations that the postapocalyptic landscape suffers an absence of popular music, movies, or fun of any sort. At times she herself drifts into hallucinatory madness.

A third person rounds out our cast of characters. This is Rocky, a motorcycle enthusiast who was Darlene's boyfriend before she fled him and by chance blundered into Markel. When Rocky catches up to Markel and EM, he demands the woman formerly known as Darlene back, threatening to pursue Markel and kill him. Markel shoots Rocky down, but a few days later, as Markel and Earth Mother are driving to California, the black clad motorcycle rider shows up again, and Markel shoots him down a second time. But soon Rocky is pursuing them anew. Markel and EM march up a mountain on foot, where Markel lays traps for Rocky and succeeds in capturing the preternaturally persistent biker.

Markel experiments on the captive Rocky, killing him in various ways and observing as his body heals and he revives; Rocky, it seems, is an unkillable mutant. Markel tries to come up with a way of neutralizing Rocky, but success eludes him and the ending of "Wings of the Phoenix" is an ironic downer. Just as Markel is finally becoming attracted to the dim-witted Earth Mother (she having lost weight on their adventures), Darlene decides that, after all, it is Rocky who is the more suitable boyfriend and she kills Markel, dooming the Earth to repopulation by stupid unkillable mutants.

"Wings of the Phoenix" has too many jokes, which sort of undermine its bleak noirish plot, the themes of which are madness and futility, but I like the basic plot outline and the story is not badly written, and the characters' behavior, mental deficiencies and physical and psychological peculiarities are certainly strange and memorable. We'll give this one a passing grade.

|

| Emsh illustrates six ways Markey tries to kill Rocky; here are two |

"The Grantha Sighting" by Avram Davidson

Merril recommended two stories by Davidson, one of which, "Present for Lona," we read back in 2019. "The Grantha Sighting" is a joke story and a waste of time.Basically, a childless couple lives on a farm in rural upstate New York and the wife at least finds it sort of lonely and boring. Luckily, a UFO lands nearby and the alien occupants, a married couple with a baby, require their help--the human husband helps the alien husband repair the flying saucer, while the human wife helps the alien wife change the alien baby's diaper and warm a bottle of alien milk for it. Then the saucer leaves. UFO enthusiasts have seen the saucer landing and/or taking off, and come visit the remote farm to investigate. The mundane quotidian nature of the aliens' visit, as accurately described by the husband, seems to displease the UFOlogists, to raise their doubts as to the veracity of the account, so the wife claims hubby was joking and offers a more dramatic but quite fictional version of their meeting with aliens; this ensures she will have plenty of company in the coming months.

The story of the sighting is actually embedded in a frame story in which a radio talk show host comes to the farm house to record an interview of the couple. Davidson takes pains to reproduce the cadence and manner of speaking of the radio host and his interviewees with strategically placed italics and additional punctuation. The closing joke of the story is that scientists are studying a piece of cloth left by the aliens, not realizing what the farm couple knows, that this artifact of a civilization from another world is a diaper.

Joke stories like this are not for me, but they have many fans. After its debut in F&SF, "The Grantha Sighting" would be reprinted in the applicable F&SF Best of anthology, multiple Davidson collections, and anthologies edited by George W. Early and by Messrs. Asimov, Greenberg and Waugh.

"It Walks in Beauty" by Chan DavisChan (AKA Chandler) Davis was a mathematician active in SF fan circles and in the Communist Party USA and related organizations. He has thirteen short fiction credits at isfdb.

"It Walks in Beauty" is about sex roles and sexual relationships in a socialistic future in which most people live in dormitories and marriage and children are permissible but considered declasse and ridiculous. Our main character Max works in a plastics or silicone factory, the not-quite comprehensible operations of which Davis describes in some detail. (It is possible the operations of the factory are a metaphor for the sex act and childbirth and it sort of went over my head.) Some of Max's colleagues in the factory are female, but because they are "career girls" they aren't referred to with the pronoun "she," but instead "it," and are not considered women, not considered sexually attractive. Only a small number of females in this society are considered women and desirable and referred to as "she;" these women live in houses and nightly perform erotic dances before audiences of men, sometimes choosing individuals among the crowd with whom to have casual sex or even short term marriages of a few weeks. (These brief marriages are called "jaypees" which I guess is derived from the abbreviation for "Justice of the Peace.") These dancers thus do get pregnant and have children. It is normal for men to fall in love with particular dancers and become their followers, sitting in their audiences nightly for weeks in hopes of being picked out of the crowd for a brief sexual encounter or even a "jaypee."

The plot of "It Walks in Beauty" concerns Max's relationship with a career girl with whom he is friends, Paula. Besides being a "nice guy," Paula impresses Max because it has a higher position than he at the factory and is good at its job. Max is in love with dancer Luana, and when he talks about Luana to Paula, it drops a bombshell--Paula and Luana were classmates in their youth, and both had the opportunity to be dancers. Luana chose the dancer route and has already been pregnant three times with three different guys, while Paula, after dancing just a few times, found itself sickened by the lustful gaze of all those men and chose to be a career girl. Paula today perhaps has some regret about her choice, or at least the fact that she had to make such a choice, and suspects that Luana may have similar regrets.

This conversation brings home to Max, a more sensitive man than most in this future world and more attuned to pre-revolutionary values (for example, he prefers old-fashioned music to contemporary music, and, unlike most men, he reads books), that current society's rules are maybe not fair to females like Paula, and decides to start using "she" and "her" instead of "it" to refer to Paula. Paula is even further along in her willingness to challenge this world's mores, and makes a bold move that ends in heartbreak. Paula contrives to get Max alone in an office in the factory, and puts on sexy clothes and a wig--just like a dancer's--and dances for Max; Paula is in love with Max and hopes he will break the rules with her and have a sexual relationship with her. But Max isn't prepared to go that far--even though he can see that Paula has a female genitalia just like Luana's, he is conditioned to see Paula as a sort of sexless semi-man, and cannot be aroused by her. He rushes off to hang around Luana's house in hopes of getting a glimpse of the dancer he loves through her window, leaving Paula to weep.

I was fully prepared to hate Davis and all his works because he is a god-damned communist but this is a good story. This is a "real" "science fiction" story in that it is full of talk about technology and science and engages in radical speculation about alternate future social conditions; Davis considers such psychological and sociological issues as to what extent our sexual desires and relationships are the natural product of our biology and to what extent they are the result of social conditioning. We might also see the story as a feminist satire of men's obsession with women's looks and of 20th-century society, a dramatizations of the pressure women feel to chose between family life and career life, between a life that revolves around love and sex and a life focused on doing productive work and achieving respect from the wider society. More importantly for those of us who look for literature or entertainment in our reading, "It Walks in Beauty" isn't a bunch of lectures or caricatures, but an affecting human drama with believable characters and real human feeling. Thumbs up for "It Walks in Beauty."

"It Walks in Beauty" debuted in Fred Pohl's magazine Star, which endured only one issue, and that is where I read it. It seems that fellow commie Pohl made revisions to Davis' story; according to Josh Lukin, editor of the 2010 Davis collection It Walks in Beauty: Selected Prose of Chandler Davis, Pohl changed the "humane tone of the story to one of misanthropic irony."

In the past I have read different versions of stories by Thomas Disch (1967's "Problems of Creativeness" and its 1972 version "Death of Socrates") and Barry Malzberg (the original versions of the stories in the fix-up novel in Universe Day as well as in that book itself) and compared them. I decided to conduct a similar investigation of "It Walks in Beauty" and read the original version of the story from the aforementioned 2010 collection edited by Lukin.

(The original version of "It Walks in Beauty" was first presented to the public in September of 2003 in Ellen Datlow's webmagazine Sci Fiction.)The version in Star includes some additional material at the start of the story, introducing earlier the fact that the pronoun "it" is applied to career girls and giving some additional screen time to a minor character. Pohl's big changes are to the ending. In Davis's original version, Max's love for Luana is extinguished, partly by Paula's dance, partly because Luana has started a new jaypee, and while things are ambiguous, Davis leaves open the possibility that Max will realize Paula is his real love.

While Davis's original ending is more hopeful, and perhaps makes more sense, in light of all the indications that Max is different from most men of his time and is evolving in his attitude towards career girls, Pohl's tragic ending has more impact and is more satisfying and easy to understand because it is so definitive.

**********

One of the virtues of this Merril-centric project is that I am nudged to read stories I might otherwise not consider because their authors have only three stories listed at isfdb or are hard core socialists, and sometimes, as today, those stories are good.

More 1950s SF in the next exciting episode of MPorcius Fiction Log.