(Before we get to today's three stories, let me note that I have already blogged about four stories that Merril chose to reprint in SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy Second Annual Volume: Theodore L. Thomas's "The Far Look," Damon Knight's "Stranger Station," Algis Budrys's "Silent Brother," and Mack Reynolds's "Compounded Interest.")

*Links: W Moore, J Brunner, H Fast, F Brown, R Bretnor, R G Brown & K Amis; Anderson, Ballard, Blish and Budrys; Clarke, Kapp, Knight, Lafferty, Leinster; Matheson, Pohl, Reynolds; Simak, Sturgeon, Tubb

"The Man Who Liked Lions" by John Bernard Daley (1956)

This is a pretty good adventure story about psychic time travelers from Atlantis chasing each other in 20th-century America. It is also one of those misanthropic SF stories about how people (or at least 20th-century Americans) are fat violent dopes. (If Daley thought Americans were fat in 1956, I can only imagine what he would think today!)

The story takes place in a zoo, and we get lots of little examples of humans mispronouncing words, saying stupid things, trying to get the caged animals to fight and just trying to kill the caged animals, as well as descriptions of women's fat asses and even fat toes(!) and men's bald heads and sagging stomachs. The main character reminisces about how he used to hunt humans back in ancient times, and compares the zoo animals of the 1900s to their much larger ancestors back in the age of Atlantis. This renegade time traveler (and Daley) compare modern humans to chimps. This story is a feast for you haters out there! (Maybe this is what Futurian Merril liked about it.)

In the climactic fight the opposing groups of Atlanteans use their mental powers to enlist the aid of the various zoo animals; the main character takes time to make sure the lions kill some humans--slowly to make sure they suffer!

A solid piece of work I can especially recommend to all my readers who are animal rights activists: you get to build up your anger by witnessing people abuse and exploit animals, and then savor the catharsis of seeing the animals massacre both Atlantean psykers and American deplorables!

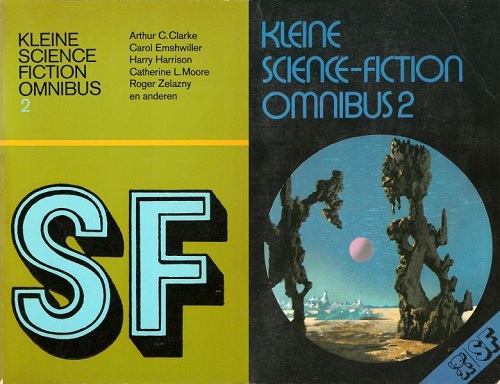

This is a professional performance, but Daley only has three story credits at isfdb. "The Man Who Liked Lions" debuted in an issue of Infinity Science Fiction with a hubba hubba cover by Emsh which is reminding me of the bookends I just bought at the big antique show. (We read the Algis Budrys cover story from this issue in 2019.) In the 1970s Daley's story of mistreated beasts would be included in a Dutch anthology which went through two different editions.

You'll perhaps remember that Merril was eager to have stories about the Himalayas in the sixth of these anthologies, and so included a 1951 story by Reginald Bretnor about an arrogant white mountain climber and a wise native psyker in 6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F along with all the stories first printed in 1960. Well, SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy Second Annual Volume provides evidence she had a history of bending her own rules--it turns out that while Merril first saw "When Grandfather Flew to the Moon" in the Canadian magazine MacLean's, it had already been printed multiple times in England in 1955 under the title "Return of the Moon Man" after winning a story contest put on by the London Observer.

This is an absurdist joke story which may be an extended riff on the supposed backwardness and stupidity of Welsh people. It is the future, the year 2500, but somehow a Welsh farm family has just gotten electric lights installed and the British people are just sending up their first rocket to the moon. Despite this, in the neighborhood lives a man who is an expert at repairing spaceships, so when the sceptered isle's first rocket, en route to Luna from London on its maiden voyage, crashes on the farm, it is quickly put to rights. One of the astronauts has repented of his commitment to exploring space, so Grandfather is aboard in his place when the ship blasts off from the farm. Grandmother is astonished by this behavior and every night goes out to look at the Moon in hopes of seeing her husband. When the new moon comes she figures her husband has died, she thinking the moon is gone because it is invisible. Making lemonade from lemons, she declares she never liked Grandfather and marries a guy with a time machine. When Grandfather gets back he acquires his own time machine and chases his bigamist wife and her new husband back in time, eventually catching them and stranding Grandma in the past by wrecking her second husband's machine.

In the same way I suspect, but am too ignorant to know for sure, that Malpass's story is exploiting stereotypes about Welshmen, there is also a sort of recurring joke that people are named after their professions (Grandma's second husband is named "Llewelyn Time Machine" and the guy who fixes the moon rocket is referred to as "Uncle Spaceship-Repairs Jones") that may have resonance with a person more educated than myself.

The tone and style of "When Grandfather Flew to the Moon" reminds me a bit of R. A. Lafferty's work, but somehow it is not fun or interesting. I'm calling this one a waste of time.

We learn on wikipedia that Eric Malpass was a banker who became a novelist; his historical novels were more successful in Germany than in the Anglophonic world. (Insert David Hasselhoff joke here, Michael.) He only has two stories listed at isfb. "When Grandfather Flew to the Moon," under that title and its original title, would continue to be printed in anthologies in the 1960s.

Merril is a big fan of Bretnor, and in her intro to "The Doorstop" tells us that his story "The Past and Its Dead People," which was printed in F&SF in 1956, "was to my mind the finest single story to appear in any science-fantasy magazine during the year." But she couldn't include "The Past and Its Dead People" here in SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy Second Annual Volume because "it is neither fantasy nor science fiction." I thought the whole rap on Merril was that she was against genre boundaries and was devoted to trying to bust them down, but I guess she is also the kind of woman who zigs when you expect her to zag. (Anyway, we'll read the alleged top story of 1956 in the near future.)

Country physician Dr. Cavaness is sitting in on a government meeting among military men and scientists. On the table under a bell jar is a strange complicated mechanism, a device which, when he looks at it, strikes the doc as queer, as if it doesn't fit in to our world. We get flashbacks to the doctor's youth in farm country and pivotal events in his more or less mundane life, and then flashbacks to how he discovered this outré device--his wife was using it to hold a door open--and decided to show it to a friend who is an electronics engineer. The authorities have figured out that it is a sort of detection or tracking device, made of materials that have never been encountered in our solar system and powered by some undetectable source of energy, and must have arrived on Earth less than a month ago. Dr. Cavaness is severely disoriented by the realization that super advanced aliens from a distant star must be nearby and that how he looks at the universe, and how the human race lives, must radically change.

While a hard science-fiction story, "The Doorstop" has elements we recognize from Lovecraftian tales--the place or thing that feels disturbingly alien, and the sanity-shaking realization that our place in the universe is not what we thought it was. The spirit of Bretnor's story is not a hopeful one; the scientists suspect the alien device is used to direct weapons fire, which hints that the aliens are not necessarily a bunch of do-gooders who will solve all our problems for us, and Cavaness feels his world "dissolving" around him and scrambles for a psychological defense mechanism that will allow him to doubt the disturbing reality that the universe is full of "unthinkable" alien life and we humans are about to meet some of it.

Pretty good.

"The Doorstop" debuted in John W. Campbell Jr.'s Astounding and lay dormant for like thirty years after its appearance in Merril's anthology, until 1988 when Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg revived it for inclusion in the 18th volume of The Great SF Stories.

**********

Two hits, one miss. We'll see how fares the next batch of three stories reprinted by Judith Merril in SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy Second Annual Volume in the next episode of MPorcius Fiction Log.

No comments:

Post a Comment