I love the cover of my copy of Dell's 1962 paperback edition of Judith Merril's 1961

, which features a yellow sphere created by John Van Zwienen. Often in life we will find it easy to love exteriors, only to be disappointed with what lies beyond them. But let's crack open this baby with hope in our hearts and read seven (lucky!) stories by people with whom we already have some familiarity--though not necessarily a fond familiarity!

(First, we'll note that we have already blogged about two stories that appear in 6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F. I liked Arthur C. Clarke's "I Remember Babylon" and I didn't like "Old Hundredth" by Brian Aldiss. Also, I'll point out that the Lester Del Rey contribution is a half-page poem, a parody of the 23rd Psalm that takes as its topic the dangers of nuclear weapons; that the Ray Bradbury contribution is an essay I haven't read; and that the Walt Kelly contribution is a lame two-page comic strip while the Shel Silverstein contribution is a four-page comic strip depicting a TV that eats people. Part of Merril's editorial project is expanding the definition of what constitutes SF as well as expanding recognition of SF in media other than traditional prose.)

volume. I liked that story, so I have some hopes for "The Fellow Who Married the Maxill Girl," which is the longest story we are reading today, taking up 28 pages of

This is a sappy story about how a poor rural family during the Depression takes in an alien and their lives are enriched by this E.T.'s miraculous powers to heal people's skin disorders, double or triple the hens' production of eggs and the cows' production of milk, and on and on; this guy has lots and lots of powers. The alien can't speak English upon arrival, but his alien speech sounds like music that makes everybody "stronger, kinder, more loving." "The Fellow Who Married the Maxill Girl" is also one of those misanthropic SF stories that offer us a goody goody alien as a means of throwing human evil into stark relief. The alien doesn't eat meat or other animal products, and he hates machinery. He doesn't feel anger or hate, and doesn't even understand those concepts. He has no interest in possessions--he refuses to sully himself by touching money--or power--he never tries to sway anybody or assert his independence from the patriarch of the family, Malcolm Maxill, an incompetent moonshiner and bootlegger, who exploits his abilities to get rich.

Maxill's daughter, Nan, who falls in love with the extraterrestrial, endeavors to hide his powers from the outside world, as she knows they will excite the greed and envy of our horrible human race. Nan marries the alien and they have a child, and she knows she will have to conceal E. T. Jr.'s superpowers as well. Luckily, Dad then dies in a car wreck so Nan and her husband are free of him.

After married life of some twenty years, during which Nan's husband does not age, hubby has to return to his people to help them through a crisis. I guess we are expected to believe he never returns but he has made Nan a better person so it was all worthwhile.

I generally don't like sappy stories, and I generally don't like stories in which the author creates a super being or super society to dramatize his banal and boring criticisms of America or the white man or capitalism or humanity or whatever. And I don't like "The Fellow Who Married the Maxill Girl."

I've actually never blogged about anything by the famous and prolific John Brunner. The things I hear about his famous works make me suspect they would irritate me, and when, in my pre-blog days, I read two of his minor works,

Maze of Stars and one of the Traveller in Black books, they were not entertaining enough to inspire in me a desire to read anything else by Brunner. Regardless, I decided to read "Report on the Nature of the Lunar Surface" because it is only two pages long and it made its debut in John W. Campbell Jr.'s

Astounding and

Astounding and Campbell's career interest me.

This is a joke story, a report from the first men to land on the moon that informs the authorities that the moon is made of green cheese; you see, some time ago a careless person dropped a sandwich into an unmanned reconnaissance rocket, which subsequently crashed on the moon--the lunar surface has proven to be an ideal medium for the propagation of the sandwich's cheese. (Is that how cheese works?)

Waste...of...time.

I have to admit that I am taken aback that serious people like Campbell and Merril would print such a thing, and it is not just them: "Report on the Nature of the Lunar Surface" would be reprinted in at least four later books, including one edited by Robert Hoskins and another by Hal Clement. smh

"The Large Ant" by Howard Fast (1960)

Back in 2016, when we were young,

I read three stories by Stalin Peace Prize recipient Howard Fast and said they were "repetitive polemics pushing tired and discredited ideas that lack literary or entertainment value." (Hmm, nowadays I would say they were "repetitive polemics that push tired and discredited ideas and lack literary or entertainment value." Oh, well.) Despite that denunciation, here I am reading another Fast production.

I must report that this is another lame lump of junk. In "The Large Ant," Fast, whom Merril presents as some kind of mastermind in her little intro, just rehashes in a limp way SF concepts we've already read many times. There is the noble alien who knows nothing of murder and is used to show, by contrast, how monstrous are human beings. Fast also throws in the ideas of collective consciousness and of aliens sitting in judgment of the human race. Three SF cliches with which "America's foremost chronicler of historical rebellion," as Merril calls him, does absolutely nothing new or fresh. And it is not like Fast unleashes some brilliant literary style on us in this story--the style is totally ordinary.

A New York writer is taking a little vacation in the country, fishing and practicing his putting. While reclining he suddenly sees an ant over a foot long right by him--reflexively he smashes it with a putting iron. When he takes the dead specimen to a scientist he learns that these oversized ants are popping up all over, and whenever a man sees one he responds by instantly destroying it. But these aren't ants--they are intelligent aliens, as evidenced by the little tools they carry in camouflaged pouches. The fact that every single encounter with these aliens results in an immediate instinctive act of murder proves how evil we humans are. It is assumed by the scientist and his colleagues that these aliens enjoy a collective consciousness, are peace lovers who can't conceive of murder, and may destroy the human race after judging our behavior.

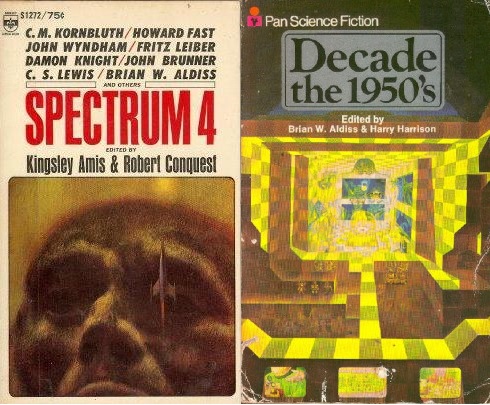

After first appearing in Fantastic Universe, "The Large Ant" would reappear in a host of anthologies, including ones edited by Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison and Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest. Did editors reprint this dross because they hoped that some of the prestige of Fast would rub off on the SF ghetto? Or did they love its message, that we are all a bunch of irredeemable jerks and deserve to be killed and wouldn't it be better if we enjoyed collective consciousness instead of individual autonomy. (Stalin Peace Prize, indeed.)

Sheesh.

"Abominable" by Fredric Brown (1960)

Remember

back in 2018 when we read Anthony Boucher's praise of Fredric Brown's short-short stories, a form which Brown calls "the vinny?" "Abominable" is one of three Brown "vinnies" that appeared together in

The Dude. The "magazine devoted to pleasure" misspelled Brown's name on its cover, a goof also committed by the people at Dell on the contents page of

6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F. Sad.

A famous film star, an Italian sex symbol, has been captured by the yeti. The world has given her up for lost. But a British adventurer who is the sex symbol's biggest fan has not abandoned hope. He ascends the Himalayan mountain where she disappeared. When he sees a yeti he shoots it down. But a second yeti captures him and explains the secret of the yeti. These beings are humans transformed into monsters by drinking a chemical. The tribe of yeti periodically captures people to turn into yetis to help maintain the yeti population, and the yeti the Englishman just killed was the Italian actress! And now he too will be forced to become a yeti--the yeti who captured him is a female and she already has the hots for him.

Barely acceptable filler. "Abominable" has been included in many Brown collections.

"The Man on Top" by Reginald Bretnor (1951)

Merril wanted to include multiple stories about the Himalayas in her anthology because the abominable snowman had been in the news a lot in 1960, and she came up with three; this is the third. "The Man on Top" was actually first published in 1951, in

Esquire, but Merril considered it eligible for publication in

6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F because it was reprinted in

F&SF in 1960. I think it is fair to wonder if, in an effort to be cute or funny, Merril wasn't drifting away from her book's stated purpose of showcasing the best fantasy and science fiction published in 1960.

"The Man on Top" is a story that contrasts the terrible arrogance and inhuman technology of the white man with the serene wisdom of the East, and has a twist ending that is cheap and lame. Instead of demonstrating the alleged superiority of the East, it just asserts it in an unconvincing manner. Maybe I am exaggerating the ambition of the story, though--maybe "The Man on Top" is just supposed to be a light joke story.

Barbank is a rich jerk who wants to be the first man to reach the summit of the world's highest mountain. He has contempt for the Sherpas, thinking he doesn't need their aid, that he can use superior equipment and techniques that he himself has designed to get to the top of the mountain. He launches the expedition with ten other white men, including the narrator. You might call the narrator a nice liberal; he always has nice things to say about the Sherpas and he is so turned off by Barbank's arrogance that he decides to sabotage Barbank's ambitions, to make sure Barbank does not succeed in becoming the first man to reach the peak of the world's tallest mountain.

Before the expedition departs, they go visit a local Holy Man, a guy in a loin cloth who has a beautiful face and serene affect and imparts words of wisdom, etc. The Holy Man tells Barbank that Barbank cannot achieve his heart's desire without the Holy Man's help; Barbank scoffs.

The march up the freezing cold mountain is challenging, but Barbank's plans work and he and the narrator approach the summit. The narrator proves that he is the stronger, and could race ahead and become himself the first man to get to the top of the world, but decides to let Barbank pass him, to humiliate the arrogant jerk by patronizing him. On the peak the climbers find the Holy Man, naked and serene as ever, sitting in a little circle of warmth apparently created by his magic powers. It is not made clear how he got there, flew or teleported, I guess. Anyway, the joke ending of the story is that the Holy Man asks Barbank how he got up the mountain and acts surprised to hear a man would walk all this way.

Bretnor's story is up to the standard of acceptable filler until the end, but the climax/punchline is lame and annoying. Maybe "The Man on Top" is meant to be a shaggy dog story, but the emphasis on the contrast between the West and the East and the contrast between the jerk Barbank and the sensitive goody goody narrator suggests the story has some kind of tendentious social message to convey and is not merely meant as a joke.

"The Man on Top" would be reprinted again in an anthology of ESP stories, and by Isaac Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg and Joseph D. Olander in their collection of short shorts, which

I read from way back

in the infancy of this blog in 2014.

"David's Daddy" by Rosel George Brown (1960)

We just recently read two novels by Rosel George Brown,

Sibyl Sue Blue, the tale of a cigar-smoking sexually promiscuous lady cop of the future, and its sequel,

The Waters of Centaurus. Here's our chance to sample another of Brown's productions, a story that first appeared in

Fantastic and in 2003 was revived by Ellen Datlow for her internet magazine.

Like the Sibyl Sue Blue novels, "David's Daddy" is about a heroic female public employee. It is also a grim sad story about how horrible life is!

Our narrator is a young school teacher. Amid all the stuff in the first part of the story about how hard it is to be a teacher and how awesome teachers are there is a clue that one of the kids in the school is telepathic, can read minds and transmit his thoughts to other minds. The second part of the story is about how a creepy guy comes to the school to ask to bring his son home. The son is embarrassed by his father, a disgusting drunk and a loser who has been pushed around by others all his life. Our narrator employs the psychological tricks she uses to keep the students under control to manipulate the scary father, whom she fears has planted a bomb in the school. Then she recruits the telepath kid to read the bomber's mind and help her find and deactivate the bomb. (They put the bomb in a tub of water. Does that really work?)

The end of the story highlights how the bomber's son is ashamed ("So many things were worse than death") and how the telepathic kid must know how horrible and unreliable are people and the world because he can read minds.

This is the best story we have read yet today because it has real human feeling and on a mechanical level the plot and pacing work well--it is not a lame joke like several of the stories described above and it is not too long like Moore's story and it feels sort of fresh, not tired, like Fast's story. And yet all those stories have been reprinted more often than Brown's--the world and people really are unreliable!

"Hemingway in Space" by Kingsley Amis (1960)

Amis was seen as a major mainstream literary figure and when his

New Maps of Hell, described in cover blurbs as "A Survey of Science Fiction" and "The Book That Made Science Fiction Grow Up," was published it received a lot of attention from the SF community. Anthony Boucher contributes a three-page essay to

6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F entitled "S-F Books: 1960" and devotes a paragraph to

New Maps of Hell, which he calls "the most controversial book of the year," and notes that Merril was in violent disagreement with it. In a 1970s interview* he conducted via mail with Paul Walker, Frederik Pohl notes that in

New Maps of Hell Amis praised Pohl to the skies. But...

A few years later, Kingsley changed his wife and his politics and came to the conclusion I was no damn good at all.

"Hemingway in Space" is a five-page parody; I'm probably not familiar enough with Hemingway to really get the nuances of this thing. I am actually more familiar with Amis's work than Hemingway's; I read Lucky Jim and Jake's Thing in 2019 and plan to read another Amis mainstream novel soon.

A big game hunter and his native guide, a two-headed Martian, are taking a couple out hunting a powerful and dangerous whale-sized beast that lives in the vacuum of space. The husband is a college professor or something, and his wife is a loud, annoying, petulant, self-important nag. The hunter thinks the prof should get rid of the "bitch" but isn't brave enough to do so.

The party comes upon their quarry, and something goes wrong and the Martian dies, sacrificing himself to save the humans. The wife is more or less to blame for the catastrophe, and the prof grows the stones to put her in her place (he sends her to the galley to cook) and divorce her.

This is a pretty gentle satire--it almost reads like a sincere SF adventure story with blasters and space suits and air locks and like a straight masculine tale of how women are obstacles to an authentic life and freedom is the most important value and indigenous people are noble and the natural world is beautiful and all that. Where the parody becomes obvious is when Amis uses repetition to make those themes seem ridiculous; the hunter doesn't just call the woman a bitch once but again and again, the contrast of the blackness of the void and the brightness of the stars isn't just mentioned once but restated again and again in a single paragraph, and so forth. But "Hemingway in Space" doesn't feel like an effort to dismiss the commonplaces of science fiction or undermine those masculine values, but rather a mock-up of a mediocre effort to employ those tropes and promote those values--Amis doesn't so much ridicule the conquest of space and the pursuit of the authentic life in the wilderness as he does writers who incompetently work with these ideas.

I found this an engaging, even provocative story, as I wondered to what extent Amis was goofing on adventure SF and Hemingway, and to what extent he was emulating or celebrating them, perhaps esoterically. Amis's "Hemingway in Space" is the only competition faced by Rosel George Brown's "David's Daddy" for the title of best story we've read today.

"Hemingway in Space" debuted in Punch, has appeared in Russian and Italian anthologies (the Italian volume is adorned with a terrific repurposed Karel Thole illo) and was chosen by Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison for their anthology of representative 1960s SF stories.

*You can read it in Walker's Speaking of Science Fiction.

**********

So we read seven stories from 6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F today, and only two of them were good (luckily they were the last two, so I can walk away from this blog post with a smile on my face instead of a scowl.) It seems I am not on the same wavelength as Judith Merril and the legions of people who are always extravagantly singing her praises (see contemporary extravagant praise below.)

|

The first two quotes are from the back cover of

6th Annual Edition: The Year's Best S-F;

the four quotes that follow are from the first page of

the anthology |

I read that Merril anthology when it was first published. Like you, I found the stories hit-or-miss. I suspect Donald A. Wollheim started his YEAR'S BES SF series as a reaction to these New Wave stories that a lot of readers didn't care for.

ReplyDeleteI wonder how well the various yearly anthologies sold, how much critical acclaim tracked with popularity among paying readers. Malzberg claims that Wollheim told him that Merril's famous New Wave anthology, England Swings SF was "the worst-selling Ace paperback in history," but maybe Merril's Year's Best S-F volumes, of which there were twelve, were profitable.

Delete