The Unexpected is an anthology edited by Leo Margulies and published by Pyramid in 1961 and then again in 1962 with an inferior cover and a higher price. The book's eleven stories are advertised as "hair-raising" and "uncanny," which sounds like what we are looking for, life being so boring and easy nowadays. We've already read some of the contents of The Unexpected in other publications: it feels like just 24 hours ago I endured Robert Bloch's joke story/feeble satire of comic books "The Strange Island of Dr. Nork;" in July of last year we read Manly Wade Wellman's Civil War fantasy "The Valley Was Still;" and in 2019 we read Ray Bradbury's cynical and gruesome "The Handler" and Theodore Sturgeon's very effective "The Professor's Teddy Bear." Let's sample more of what The Unexpected has to offer today, three pieces that include stories by women contributors to Weird Tales, Margaret St. Clair and Mary Elizabeth Counselman, and a famous story by the creator of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, Fritz Leiber.

Saturday, May 3, 2025

The Unexpected: M St. Clair, M E Counselman & F Leiber

Monday, March 10, 2025

Galaxy, Feb '68: P Anderson, T Carr & A Panshin, and F Leiber

"A Tragedy of Errors" by Poul Anderson

isfdb lists this one as being part of the Technic Civilization series, and it has been reprinted in the collections The Long Night (in the 1980s) and Flandry's Legacy (in our own crazy 21st century) among a few other places. I'm reading the magazine version of "A Tragedy of Errors," which is graced with four illustrations of space craft and people in space suits by Gray Morrow, though I am consulting a scan of the Sphere edition of The Long Night when I come upon a confusing typo, like a "have" on page 14 of the magazine where I would expect to see a "haven't." (The book version has "haven't.")

"A Tragedy of Errors" takes place in "The Long Night," the time period after the collapse of the Terran space empire when the human race, now inhabiting thousands of star systems, becomes fragmented, people having lost the ability to build space ships and repair many of their electronic systems, though surviving space ships can still be operated on manual, though at additional risk and lesser efficiency. Our hero is Roan Tom of planet Kraken, who, I guess Viking-like, travels hither and thither in a space ship, raiding and trading as he sees fit. He has multiple wives and lots of tattoos. Anderson spends perhaps too much time describing what he and the two of his wives that appear in the story look like--Anderson loves to describe stuff, sunsets and the wind in the trees and that sort of thing.

The plot of "A Tragedy of Errors," which is like 56 pages or so here in Galaxy, concerns Tom and the two wives he has with him, one the chief wife he's been with for quite a while, a seasoned spacer with whom he has grandchildren, and the other a new acquisition, young and inexperienced, having to land on a planet hoping it has the industrial capacity to repair their damaged ship. They find the natives are very wary of strangers, having been raided in the recent past; the central gimmick of the story is that the English language has evolved differently in different spots since human civilization fell into isolated pockets with the collapse of the Empire, and this makes negotiations between Tom and the locals difficult and leads to bloodshed.

Our heroes get split up, the women fleeing the crash-landing site of Tom's ship into the wilderness while Tom tries to negotiate with a member of xenophobic local aristocracy. The older wife, many adventures behind her, teaches the younger city-bred wife how to survive, and the younger grows as a person in response to the challenges she faces. Tom uses logic and his practical knowledge of science and technology to reunite with his wives, and then the younger wife uses her book-learned science knowledge and facility with math to figure out the mystery of this star system's age and this planet's erratic weather, information Tom sells to the local potentate as part of his negotiations to make peace and lay the foundations of a mutually beneficial commercial relationship. In the denouement we find the younger wife becomes a successful diplomat.

I still enjoy reading about and thinking about aircraft, spacecraft, spacesuits with anti-grav so you can fly around in the atmosphere like a bird and that sort of thing, and Anderson delivers on that fun stuff. He also includes lots of astronomy, sociology and ecology stuff, always telling you that this or that geographic or meteorological feature is the result of the proximity of this moon or elevated solar radiation or whatever, and always offering speculations on how people who live in the ruins of the superior civilization of their ancestors might think and behave. "A Tragedy of Errors" is adventure fiction about people fighting and trying to evade capture or escape captivity, but it is also serious science fiction informed by Anderson's knowledge of science and history and full of little lectures. And there is a plus for our feminist friends--Tom's wives are instrumental in resolving both the action and the number-crunching obstacles presented by the plot.

I can mildly recommend "A Tragedy of Errors." You might justly call it an unspectacular standard-issue Anderson space story, but it is competently told and I appreciate its pro-science and pro-trade values, and I enjoyed it.

"The Planet Slummers" by Terry Carr and Alexei Panshin

In the course of this blog's apocalyptic life we've read Terry Carr's stories "Castles in the Stars," "The Dance of the Changer and the Three," and "In His Image," as well as Carr's novel Cirque. As for Alexei Panshin, we've read "The Destiny of Milton Gomrath" and "Now I'm Watching Roger." (I'll also note that, before starting this blog, I read Panshin's famous Rite of Passage and really liked it.) "The Planet Slummers" is four and a half pages long and seems to never have been reprinted. We're all about the deep cuts here at MPorcius Fiction Log.

"The Planet Slummers" is an absurdist joke story perhaps set in another universe--in the first column we learn that our protagonists, Dave and Annie, have purchased an Edsel with a "Dewey for President" sticker on it and driven it to England. The core joke of the story is that Dave and Annie and their circle of friends are hipsters who buy things "ironically"--D & A have a picture of Mussolini in their house with a joke word balloon affixed to it, for example, while a friend who bought a pet bandicoot did so because he thought "bandicoot" sounded funny. After we see these two jokers in action at a rummage sale, a UFO lands near them and they are accosted by a pair of space aliens who are just like they are--these E.T.s are frivolous people who collect stuff not because they admire it or can make use of it but because they think it is funny. The aliens seize Annie because they think she is amusing and fly off with her, leaving Dave on Earth to worry that, like that bandicoot, she is doomed to some black fate when the aliens find something funnier.

For what it is, "The Planet Slummers" actually works--Dave and Annie, and the two aliens, actually sound and act like the sort of people Carr and Panshin are spoofing--I know these sorts of people, and my wife and I, who, as my twitter followers may have noticed, spend a lot of time at antique stores and flea markets, might even be considered akin to these sorts of people. So even though this is a trifling joke story I'll give it a grade of "acceptable."

"Crazy Annaoj" by Fritz Leiber

Many a time at this blog I have noted the somewhat unusual sex content in Fritz Leiber stories, and today I get to do so again. Sadly, I also have to tell you that "Crazy Annaoj" is a rather weak story in which little takes place and which lacks any compensatory charms, the style and images and relationships and jokes being quite bland. I guess we can call it acceptable.It is the far future when mankind has explored multiple galaxies and colonized untold numbers of worlds. The richest man in the human race, Piliph Foelitsack, is like 400 years old, but looks and even mostly acts like he is in his early 20s because he's had so many treatments and his body is full of gadgets which a team of doctors aboard his space ship Eros monitor and control remotely 24/7. He has just married his seventeenth wife, Annaoj, a woman 17 years old who managed to catch his attention when she was a 16-year-old beauty-contest-winner and actress in a virtual reality porno film. Piliph is the richest man in human civilization, having risen out of a ghetto to become owner of multiple planets and a fleet of hyperspace freighters. Wife #17 Annaoj was born in a slum herself and her drive, intelligence and ambition are comparable to his.

On their honeymoon the couple visit a gypsy fortuneteller. One of the themes of this little story is that no matter how scientific, no matter how high-tech, a civilization may be, many of its members will be fascinated by the supernatural and the occult, and will act irrationally when it comes to love and sex.

The gypsy tells the bazillionaire that he is young and his longest journeys lie ahead of him. Piliph and Annaoj don't believe her--Piliph has travelled widely across the universe but just recently decided to stick to the Milky Way galaxy from now on in order to remain close to the best health professionals and facilities. Just after leaving the gypsy, Piliph's body gives out and he collapses--the doctors freeze him in hopes that new technologies will be developed that can revive him.

Annaoj takes over Piliph's business empire and runs it as well--maybe better!--than did he, its founder. She also spends a lot of time travelling all over the universe, trying to find somebody with the ability to revive her husband, visiting not only the foremost scientific medical men but also witch doctors, mystics and sorcerers. Annaoj has sex with lots of men, but her heart remains with her husband, and oft are the times she will lay down to sleep next to his frozen body. The Eros carries her and her frozen husband to so many extragalactic locations over so many centuries that the gypsy's prediction comes true. After searching the universe for a way to revive her beloved for over 1,000 years, the Eros fails to return from one of its jumps into hyperspace, the ship and Annaoj vanishing.

This is one of those stories that I like more thinking back on it than I did while reading it. While I was reading "Crazy Annaoj" it felt slight and bland, but looking back the plot seems good--maybe I should say I feel the story is underdeveloped, that it is like a plot outline or summary that would benefit from fleshing out.

"Crazy Annaoj" has been reprinted in the Martin H. Greenberg, Charles G. Waugh and Jenny-Lynn Waugh anthology that has appeared under the titles 101 Science Fiction Stories and The Giant Book of Science Fiction Stories as well as Leiber collections. The covers of the collections suggest this story is both rare and one of Leiber's own favorites. Hmm.

**********

A decent batch of stories--any group of stories that doesn't include any bad ones is to be commended. But I'm not actually in love with any of them. Maybe love awaits us when we read the stories from this issue of Galaxy by Aldiss, Lafferty and Laumer. Fingers crossed!

Tuesday, February 11, 2025

1974 "Dazzling" stories: Busby, Effinger, Leiber

But first, you can check out my dumb twitter joke about this cover.

And tarbandu's blog post about Patrick Woodruffe.

"If This is Winnetka, You Must Be Judy" by F. M. Busby

Years ago I read Busby's To Cage a Man and thought it alright and two Rissa Kerguelen books and found them "competent" but "long and flat." All three of those novels, at least as I recall them, spent a lot of ink describing people suffering abuse and trauma, and the Rissa books in particular were full of fetishistic sex. Well, let's see if Busby crams this approximately 25-page story full of torture and perversion.

"If This is Winnetka, You Must Be Judy" feels a lot like boring mainstream fiction about a writer guy who keeps getting married and divorced and who has trouble keeping his attractive wife of whom he is fond from finding out about his attractive mistress of whom he is also fond and doesn't really know what he wants or how to get it, etc. We get lots of conversations with women about relationships, lots of assessment and comparison of women's personalities and bodies, lots of sexual encounters, etc.

Our narrator is Larry Garth, a writer who gets married at least three times and divorced at least twice. He doesn't live his life in linear order, from birth to death--instead, he hops around, backward and forward, often waking up in the morning in a different period of his life, able to recall some chronologically later parts of his life, which he has already experienced, and only some, but not all, chronologically earlier parts. This, as you would expect, causes problems because he may not remember what happened yesterday, but knows that the woman he finds in his house, wife number two, say, is attractive and fun today but is going to be an obese drunk in a few years and he is going to divorce her, and has to pretend he knows the past and doesn't know the future. To help himself he leaves little notes in his wallet and a safe deposit box at the bank, and tries to memorize things. There are also advantages--when experiencing a middle-aged period of his life he reads some of his early novels and then when he is experiencing that younger portion of his life it is easy to compose the novels from memory.

I seem to recall reading stories about people with telepathy, about how they feel alone, and then the big moment of the story is when they finally meet another telepath. Ed Bryant's "The Silent World" is one such story, and I am sure there are others. I read Robert Silverberg's Dying Inside in my New York days, long before this blog emerged soft and vulnerable from its chrysalis, and I suspect meeting another telepath is a major event in that book. Anyway, Larry Garth realizes his third and favorite wife is also a person who lives her life out of sequence when he sees her before they have chronologically met and recognizes her, and she recognizes him in turn. This is a period during which he is living with, but has not yet married, wife #2. To spend time with wife #3 requires a little sneaking around. More importantly for us SF fans, as in a lot of time travel stories, the time travelers grapple with whether or not they can change history. In this happy ending story the protagonists can change history--Garth figures out how to avoid marrying wife #2 and hook up with wife #3 early; wife #2 never gets fat or becomes a drunk and has a happy marriage with some other guy, and wife #3 escapes dying of breast cancer by taking that lump more seriously than she did in the previous, no longer operative, time line.

We'll call this one barely acceptable. I think it is kind of boring, but Lester del Rey, Jacques Chambon, and Leigh Ronald Grossman all included "If This is Winnetka, You Must Be Judy" in anthologies. Maybe we should see it as a typical example of New Wave writing, a sort of conventional mainstream fiction narrative with some science fiction trappings.

|

| Two years ago we read the Lafferty story from del Rey's fourth Best Science Fiction Stories of the Year, "And Name My Name," and I really liked it. The included story by Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth, "Mute Inglorious Tam," I read two months ago and called an "acceptable" "gimmick story." |

"How It Felt" by George Alec Effinger

...not just U.S. beetles, but coleopts from all over the world--slant-eyed Asian beetles in golden robes, North African beetles in burnished burnooses, South African beetles wild as fire ants with great Afro hairdos, smug English beetles....I'm not against ethnic jokes per se, but just saying "Asians have slant eyes, black people are wild and English people are smug" isn't actually a joke--it's more like a list of ungenerous observations and questionable stereotypes.

...the New York City cockroaches were out in force, picketing the convention....Round and round the sacred grass plot they tramped, chanting labor-slogans in thick Semitic accents and hurling coarse working-class epithets.

"...many of them are mere German (German-Jewish, maybe?) Croton bugs, dwarfish in stature compared to American cockroaches, who all once belonged to the Confederate Army."There isn't much plot to this story--mostly it consists of these kinds of anemic jokes. Leiber manages to work in a few references to rape--studying an English word, the beetles think "B" and "R" are drawings of a snake raping another snake.

...part of a World Cockroach Plot carried out by commando Israeli beetles....His wild mouthings were not believed.

Monday, January 20, 2025

Dangerous Visions from F Leiber, J G Ballard and S R Delany

Let's get dangerous! Today we read three more stories from my First Edition of Harlan Ellison's famous 1967 anthology Dangerous Visions. We have various reasons to believe these are among the best or most important stories in DV, so maybe this will be an exciting adventure for us.

"Gonna Roll the Bones" by Fritz Leiber

Here's a story that won a Hugo and a Nebula--kaboom! "Gonna Roll the Bones," which has been reprinted a million times, is also the inspiration of the cover illustration of the edition of The Best of Fritz Leiber that I own, and, to my surprise, of a 2004 children's book.From line one, "Gonna Roll the Bones" certainly feels like a story that would win awards. It is stuffed full of long sentences filled to the brim with metaphors and similes that paint vivid pictures not of charm and beauty but of squalor and decadence. Immediately we are presented intimations of catastrophe to come, predictions of mass death.

In his intro to "Gonna Roll the Bones," Ellison tells us SF writers tend to be specialists--Edmond Hamilton and A. E. van Vogt specializing in world destruction, Ray Bradbury in poetic imagery, etc. But Leiber, your old pal Harlan opines, is a master of all forms, from fantasy to science-oriented "hard" science fiction. "Gonna Roll the Bones" demonstrates this. The story has a sort of Olde World fairy land setting, but is full of references to space ships and alien life forms and astronomical phenomena and is set in the spacefaring future--many of the metaphors and similes are references to space craft:

While among the trees the red-green vampire lights pulsed faintly and irregularly, like sick fireflies or a plague-stricken space fleet.These metaphors and similes don't necessarily make a lot of literal sense, but strike a mood or fashion an image.

Joe Slattermill works in a mine and lives with his mother and wife and cat (SF people love cats and we hear plenty about the cat.) Mom and wifey make additional money as bakers and the house has a huge fireplace and series of ovens and Joe expects someday the place will burn down, killing all inside.

Stir crazy, Joe, known to gamble and get drunk and beat his wife, heads out to raise hell. There is a new gambling hall on the dark side of town full of sexy girls and craps tables--presiding over the "Number One Crap Table" are the fattest man Joe has ever seen and a pale woman who is alarmingly tall and skinny whose role is to collect the dice once they are thrown. But even more prominent, and obviously in charge de facto if not de jure, is a mysterious figure in black, his face partially obscured, a perfectly poised gentleman gambler. Leiber describes all these people, and the dice and the table, in great detail. As I read of topless girls, the excitement in Joe's crotch, the man in black groping a girl's ass and then killing a guy with a karate chop to the throat, and Joe's and the gentleman in black's use of derogatory terms for people of African descent, I kept wondering what the hell was in that 2004 kid's book. (It turns out the text in that book has been abridged down almost to nothing by Sarah L. Thomson--the main point of the volume is the pictures by three-time Caldecott winner David Wiesner, which are very bland and unfinished and do absolutely nothing to convey the apocalyptic tone, dark power and rococo intricacy of Leiber's baroque images--Joe the wife-beating drunk has a face with zero personality! Thumbs down for that colorless and lifeless thing!)

Joe is kind of a superhero, or a tall-tale figure like Paul Bunyon, when it comes to throwing things, and he can roll dice and make them come up on the sides he wishes. He makes a stack of dough and then passes the dice on after deliberately rolling boxcars, as he wants to see the man in black, who is psychologically dominating all the assembled gamblers and hangers on, throw. The sinister gentleman can also roll whatever he wants, but while Joe makes his throws look natural, making the dice bounce around and going through the rigamarole of rolling the dice and getting a point and then rolling several times before hitting his point, the gambler in black just arrogantly rolls seven after seven after seven, flaunting his power.

The gambler in black, as Ellison hinted in his intro, is of course the devil. He wants to gamble with Joe--the stakes Joe's life and soul! Joe can back out, but he doesn't want to seem a coward. In the end, Joe wins, thanks to his own courage and his wife's love for him and faith in Jesus Christ--at least that is what I think happened; it is a little confusing. As the story ends, Joe is about to enjoy his winnings--when he put up his life and soul, the devil put up "the world," and Joe, a working-class schlub stuck in a mining town up to now, is going to see the world.

A good story that is written elaborately and can be examined from various angles--religion-based, class-based, sex- and race-based. In his afterword, Leiber explains some of what he is doing, suggesting, for example, that the story is in part about how men resent the control over them wielded by women but should recognize that mothers and wives are in fact often a critical support for men. Manifesting the spirit of old time science fiction, even here in this monument to the New Wave, Leiber urges readers to understand that the limits we see in our lives and the universe are in fact bogeymen we can brush aside if we arm ourselves with knowledge--mankind really can cure cancer and conquer the stars the way mankind has already achieved flight and embraced sexual freedom, and science and technology are the key to these overcoming these obstacles and building better lives and a better society. As Ellison suggested it would, "Gonna Roll the Bones," with its poetic style, hope for the future, sympathy for the working class, Christian themes, horror tone and embrace both of psychic powers and space-age tech, cunningly appeals to many factions of the SF community.

|

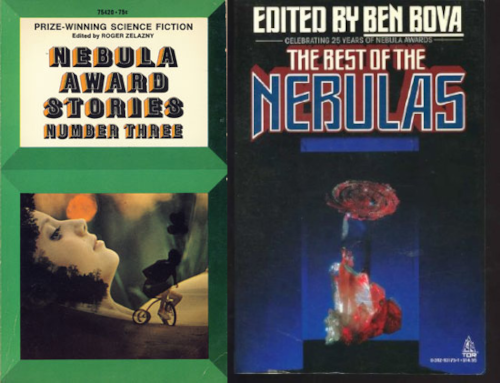

| Both Leiber's "Gonna Roll the Bones" and Delany's "Aye, and Gomorah" appear in both Zelazny's Nebula Award Stories: Number Three and Bova's The Best of the Nebulas |

"The Recognition" by J. G. Ballard

Our friend tarbandu of The PorPor Books Blog, in a December post titled "The Most Overrated Science Fiction Writers of the Postwar Era," in the section of the blogpost devoted to slagging Theodore Sturgeon, praises "The Recognition," so let's check it out."The Recognition" has not been anthologized much since its debut in Dangerous Visions, but of course it has been reprinted in Ballard collections.

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Three above the night: Leiber, Reynolds and Russell

Saturday, August 10, 2024

Merril-approved 1958 SF stories: F Leiber, J Lewis, V Lincoln

Our guided tour through the science fiction and fantasy of 1958 continues. Our guide is the New York Journal-American's favorite anthologist, Judith Merril, our map is the alphabetical list headed "Honorable Mentions" in the back of her 1959 edition of SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy. Today we'll read the four 1958 stories by "L" authors recommended by Merril, three of which debuted in issues of F&SF edited by Anthony Boucher.

"A Deskful of Girls" by Fritz Leiber

Here we have a story that is a satire of Hollywood--how Hollywood exploits women and reflects our sex-obsessed society that sees women as sex objects--as well as a feminist revenge fantasy. "Deskful of Girls" is also one of those SF stories that offers an explanation of a supernatural belief; SF writers love to come up with rational explanations for ancient religions and supernatural phenomena like the Greek gods or the Norse gods or vampires or werewolves or Medusa the Gorgon or whatever, and Leiber here speculates on the origin of the common belief in ghosts. For some reason Merril cites as its source the eighth volume of The Best from Fantasy & Science Fiction and not the magazine in which "A Deskful of Girls" debuted, so we are dutifully reading it in a scan of that book instead of a scan of the magazine.Our narrator, Carr Mackay, is on a mission: he has been hired to negotiate with Emil Slyker, the overweight psychoanalyst to the stars, a man who integrates into his practice his deep knowledge of sex and of the occult and has been blackmailing Evelyn Cordew, the current top Hollywood sex symbol. Mackay befriends Slyker and ends up in Slyker's office, seated before the man's desk, which, Slyker has told him, is full of girls, a metaphor which has got Mackay's imagination humming. Slyker is a gifted raconteur, and as he relates to our narrator the stories of Hollywood starlets and other prominent women he has known intimately as their analyst, Mackay gets a sense that Slyker is presenting to him the true essence of these women, and eventually comes to realize that Slyker has these women's ectoplasmic emanations in those folders he keeps pulling out of his desk drawers. Slyker explains that when a person sleeps or is under hypnosis, he or she sends forth an ectoplasmic form almost invisible, something like a transparent or translucent layer of skin that carries with it all of his or her genetic information as well as emotional and psychological content that can be sensed by those the ghost touches. Normally these ghosts return to the sleeper when he or she awakes, but the umbilicus that connects ghost to living person can be severed and the ghost captured. Skyler has a bunch of these ghosts of beautiful women in his desk, and he admits to Mckay that he has five ghosts of the woman in whose interest our narrator has come, reigning queen of the cinema Evelyn Cordew!

Slyker restrains and silences Mckay in a high tech chair and promises to let him see a ghost of Evelyn Cordew; a ghost can only be seen in the dark, so he turns out the lights. But then Evelyn Cordew herself, using her own high tech equipment, busts into the room and restrains Slyker. She wants her ghosts back, believing their lack has damaged her looks and thus her acting career. (Earlier, Slyker told Mckay that stealing some of Cordew's ghosts had served to relieve her of some dangerous anti-social personality traits.) The narrator watches as Cordew reunites one at a time with each of her five ghosts; this takes several pages, as Leiber dwells on the surreal movements of the ghosts as they reintegrate themselves with Cordew's gorgeous body and as Cordew herself describes the experience of slipping back into these ectoplasmic skins and narrates the course of her career, tying each ghost to the events of her life in Hollywood at the point when it was stolen from her by Slyker. This is where we get a big fat dollop of the feminism that perhaps endears this story to people like Merril--Evelyn Cordew asserts that female movie stars are not to be envied or admired but to be pitied, as they are the victims of men, exploited by Hollywood's elite and the viewing public alike; Cordew sums up her case by claiming that all men are pimps or johns. (One of the clever things Leiber does in "A Deskful of Girls" is to refuse to exempt our narrator from this charge, making it clear from the start of the story that Mckay himself is as horny and preoccupied with women's bodies as any of us. I also feel compelled to point out that plenty of Leiber stories seem to treat women as sex objects and appeal to readers' interest in somewhat off-the-reservation sex, so those inclined to read "A Deskful of Girls" and then accuse Leiber of hypocrisy have grounds to do so.)

The story ends with Slyker's death and the liberation of all the other ghosts, the destruction of all the blackmail material and the escape of the narrator with Cordew's aid.

This is a pretty dense and wordy story with lots of long sentences, lots of metaphors, lots of references and allusions. Leiber describes the layout and decor of Skyler's room, and the advanced technology both the contending blackmailer and sex symbol employ, in great detail, and there are oblique indications that Cordew and maybe Slyker are in touch with other time streams--"A Deskful of Girls" is one of Leiber's Change War stories about feuding time travelers. Leiber name drops numerous visual artists (Heinrich Kley, Mahlon Blaine and Henry Fuseli) and talks about high brow music (the Nutcracker Suite of "Chaikovsky.") Plus, Leiber offers theories of what the popularity of Hollywood actresses like Greta Garbo ("her romantic mask heralded the Great Depression") and Ingrid Bergman ("her dewiness and Swedish-Modern smile helped us accept World War Two") say about their epoch and what these screen goddesses provide to their societies.

"A Deskful of Girls" is a strong and ambitious story that is well-written and has lots going on, but it may also be one of those stories that is easier to admire than to enjoy. Leiber kind of goes overboard with the descriptions, and my eyes glazed a little bit during the passages mapping out Slyker's office and giving us a repetitive and simile-laden play by play of Cordew's reintegration with each and every one of five different ghosts ("Then, as if the whole room were filled with its kind of water, it seemed to surface at the ceiling and jackknife there and plunge down again with a little swoop and then reverse direction again and hover for a moment over the real Evelyn’s head and then sink slowly down around her like a diver drowning.") I can also imagine that people unfamiliar with Leiber's Change War stories might find the references to the Change War concept to be totally opaque.

Despite reservations, thumbs up for "A Deskful of Girls," which has appeared in many languages in many Leiber collections.

"Rump-Titty-Titty-Tum-TAH-Tee" by Fritz Leiber Here we have a long and elaborate and somewhat tedious joke story, as the title, with its puns referring to secondary sexual characteristics, perhaps warns us. I guess we can call this is a satire of 1950s culture, but while the satire of "A Deskful of Girls" has a feminist bite and still feels relevant, the satire in "Rump-Titty-Titty-Tum-TAH-Tee" feels silly and is very much of its time, the kind of thing people might dismiss as "dated."

Six intellectuals meet weekly in a large space where one of them makes splatter paintings by standing on a 20-foot high scaffold and flinging paint down on a huge canvas that takes up most of the floor. This week's conclave, Leiber tells us, coincides with a special moment when "all the molecules in the world and in the collective unconscious mind got very slippery." Another of the intellectuals is a jazz musician, the descendent of a witch doctor, who beats out tunes on an African log. At the very moment the molecules go slippery he beats out the tune rendered in onomatopoeia as the story title. The painter flings black paint on the white canvas, the resulting blobs and streaks visually representing the notes of the tune with two little titties and a big glob as the rump and so forth. All the assembled intellectuals think the musical passage and the abstract painting special, and one of them photographs the canvas and each of them leaves the meeting with a print.

Over the next week the musician becomes famous with the tune and starts a whole new movement, Drum-and-Drag, that rivals Rock-and-Roll. The psychiatrist uses the photo of the painting as a Rorschach test and his patients start having breakthroughs. Three other of the intellectuals have similar success due to the influence of the tune and/or painting on their careers. (Rest assured that Leiber offers lots of details and little jokes about all six of these hipster eggheads, going overboard just as he did with the five ghosts in our previous story.) The painter, however, has a problem. Every time he flings paint the exact same pattern appears, though he can control the size.

In succeeding weeks the other five intellectuals start suffering problems I won't describe, while social problems of wider ramification born from the tune and painting also begin to trouble the wider world. Basically, the world is addicted, obsessed, hypnotized, by the little tune and the abstract painting. One of the six, a cultural anthropologist, realizes that the ancestor of the musician, the witch doctor, has sent the musical phrase, a sort of spell, across time to them, and to save the world they have to cast a spell contacting this guy (who must be alive somehow outside the timestream) and receive from him the counterspell. To cast the spell they enlist a medium, snoke marijuana, paint pentagrams and hang garlic and on and on. Success is achieved, and everyone in the world forgets the dangerous tune and image. The final little paragraph has the medium report that the witch doctor from centuries ago is in Hell and the Devil forced him to cough up the counterspell because even the damned and demons of the underworld were getting addicted.

A lot of work obviously went into this story but it is not thought-provoking or entertaining. Gotta give it a thumbs down, though I suppose if this is your thing, you will like it, because it is not lazy or clumsy--Leiber is a smart, educated professional who set himself a goal and accomplished it--my gripe is that I do not see value in the goal he set himself.

"Rump-Titty-Titty-Tum-TAH-Tee" debuted in F&SF and people seem to have liked it; Groff Conklin included it in Science Fiction Oddities (1966) and Damon Knight in A Science Fiction Argosy (1972), a book I bought for a dollar over nine years ago. (I read the story today in a scan of the appropriate issue of F&SF.)

"Glossary of Terms" by Jack Lewis

I don't think I've read anything by Lewis before. isfdb lists nine pieces of short fiction by Lewis and one ridiculous looking novel about mercenaries who pursue money and Hitler in Latin America and on their travels encounter a nymphomaniac. "Glossary of Terms" is listed by isfdb as an "essay," but I think at a stretch it counts as fiction in the way that Brian Aldiss' "Confluence" counts as fiction--it is presented as an artifact of some other, fictional, culture and provides clues to this alien culture's nature."Glossary of Terms" is a guide for SF writers living far in the future after mankind has developed interstellar travel and time travel. Over its two and a half pages the story or article covers ten items, offering definitions and advice on usage for such things as "TELEPATHY" and "DISINTEGRATOR RAY." The entries offer opportunities for Lewis to make weak jokes and engage in banal criticism of SF. For example, in the future the "ATOMIC BOMB" will be considered a weak weapon used only in minor skirmishes. Lewis spoofs how aliens in SF often have hard to pronounce names, points out that time travel is used by authors to give them an excuse to write a fantasy adventure story, and makes a tepid joke about how taxpayers oppose foreign aid. And so on.

This story is a waste of time and I do not think it has ever been reprinted. Maybe Merril liked it because of its anemic but still dimly apparent criticism of our society for being violent, of adventure SF for being violent and nonsensical, and of taxpayers for objecting when the government ships their money off to foreigners...and probably for being violent.

"No Evidence" by Victoria Lincoln

Here's another author new to MPorcius Fiction Log. Victoria Lincoln has one credit at isfdb, but a New York Times obit suggests she wrote multiple successful mainstream novels as well as biographies of notable women like Lizzie Borden and St. Theresa of Avila. Merril, as I've told you a million times, loved to reprint and recommend SF by mainstream writers and SF that was published in mainstream venues because she thought genre boundaries were essentially bogus, and here we have another example. I guess Lincoln was well-known enough that Anthony Boucher thought it worthwhile to put her name on the cover of the issue of F&SF in which "No Evidence" appeared, below Chad Oliver's but above Avram Davidson's. A quick look online did not unearth any evidence the story has appeared elsewhere.Charley is an orphan, an immigrant from Ireland whose mother drank herself to death when he was a child. As a youth Charley always had trouble making up his mind, and was often torn between conflicting impulses; one horrible day he drowned a cat, his sadistic impulses overcoming his affection for the little creature and his sense of right and wrong. At other times he demonstrated drawing ability.

As a young adult, after a stressful episode in which he vandalized property with elaborate graffiti and stole some booze, Charley got drunk and then split into two people! The second version of himself returned to Ireland tout suite and every few years sends a letter to the Charley in America to beg for money. In the absence of the selfish, rebellious, artistic half of his personality, Charley becomes a success at work and socially, while his Irish counterpart is a drunken layabout who is forever living off others and getting in trouble.

Eventually the Irish half of Charley makes a go of it as an artist. In one of his letters begging for money he talks about how he is doing an elaborate woodcut depicting death and destruction and mentions the cat he and Charley drowned. Bitter at being reminded of this crime, American Charley refuses to send any more money, and begins having nightmares of the troubles faced by Irish Charley, who has some kind of illness that is killing him as he struggles to complete his masterwork depicting all the ways people destroy themselves and each other. Irish Charley considers this work of carving to be essential evidence of the hopeless reality of life, that hope is an illusion. American Charley begins getting sick himself, and the way he coughs while wracked by his nightmares dreams upsets his wife.

Eventually American Charley sends more money, but Irish Charley dies, and Irish Charley's much put upon wife destroys the horrifying carving. American Charley stops having the bad dreams and his health recovers, and he burns all the letters from his Irish half--no evidence remains of his bizarre double life, but his personality, it seems, never quite recovers.

The lens through which we look at "No Evidence" today is that of identity. Lincoln exercises the much discussed "duality of man" theme, the idea that everybody is capable of both good and evil; Lincoln makes this a little more interesting by illustrating the disturbing fact that talented creative people tend to be selfish jerks who live like parasites--the talented version of Charley who might change the world is also the evil one. Perhaps less hackneyed, or at least more in tune with 2024 concerns, is the theme of how immigrants have two identities--that connected to the country in which they were born and that connected to their adopted country. As a kid in Ireland, Charley was poor and the love of drink of his mother made his life a nightmare, and the half of Charley who returns to the Emerald Isle is also impoverished and afflicted with alcoholism. We might also consider the idea that drunks have two identities, a sober one and an inebriated one.

Lincoln generates tension by keeping us unsure which half of Charley we should sympathize with and admire, the boring guy who works his way up through the company or the rebel who strives to live on his own terms, exploiting others, and create a masterwork that will blow the lid off our illusions and reveal to us one and all the horrible truth of life and history.

We can call this one marginally recommendable.

**********

All four of these stories are remarkable, each at least a little off the beaten path: Leiber's two stories are ambitious and chock-full of content, in fact maybe too stuffed; Lewis's is a sort of in-joke that attacks the common run of SF; and Lincoln's story is by somebody who has not written any other SF. Even though I gave two of these stories low marks, this has still been an interesting stage of our journey through 1958. Next stop: "M!"

.jpg)