I've owned a copy of the 1974 Barry Malzberg collection

Out From Ganymede for many years, since before I started this blog, but have not blogged about many of the stories in it, in fact, I think I haven't even read many of them. So today, let's explore six of them.

But first! A list--with links!--of stories in Out From Ganymede about which I have already written here at MPorcius Fiction Log:

"November 22, 1963" (1974)

It seems this story has only ever appeared here in Out from Ganymede. The title of course refers to the date JFK was murdered, but the celebrity the story's text seems to invoke without specifically naming is Sharon Tate, described as "a film starlet who was sensationally murdered some years ago."

A guy is living in a little Manhattan apartment; apparently he is a writer and hard at work on some book. He is haunted by a hallucination or ghost of the starlet mentioned in the first line of the five-page story, and her constant chatter distracts him from his writing. She suggests she is supernaturally conjoined with his apartment, and he destroys his manuscript, abandons his home, and wanders around the city thinking of suicide. There are scenes I, as a native of New Jersey and former Manhattan resident, found interesting, the guy looking across the river to Jersey and hanging around on a fire escape, dropping paperclips down to the street. The story ends with him on that fire escape and we are left to wonder if he really does kill himself; in the last line of the story it is revealed that before leaving his apartment for good he struck down the haunting image of the starlet, as if murdering her a second time.

This offers plenty of Malzbergian themes (famous people getting murdered; the difficult life of the writer; difficult sexual relationships; insanity and hallucinations) and I like the style and individual images and scenes, but I'm not sure it coalesces into a substantial whole. What is that book that he is writing actually about? Are there any connections between the Sharon Tate figure, Kennedy, and New Jersey and New York? I'll call it acceptable.

"Still-Life" (1972)

"Still-Life" appeared in

Again, Dangerous Visions, Harlan Ellison's follow up to his famous anthology

Dangerous Visions. Curious to read Ellison's intro to "Still-Life," I cracked open my copy of ADV (as Ellison calls it—the never published third volume of the

Dangerous Visions trilogy, which Ellison advertises here in this intro, is "TLDV.") In his two-page introduction, Ellison explains

that "Still-Life" was going to be a chapter in

Universe Day, which we read back in

2018, but Malzberg agreed to leave it out of what maybe Ellison would call UD

so that all of the stories in ADV would be “never before published.” He thanks Malzberg for this, and also tells us that “in its own special

way it ["Still-Life"] is the most dangerous vision in this book.”

“Still-Life” is one of Malzberg’s stories about an astronaut

who goes insane while on a mission and ends up killing people, integrating general

themes we see in Malzberg’s work again and again, like sexual frustration, skepticism

of technology, and the inability of the government to accomplish anything, and

more space-program-specific themes like Malzberg’s belief that exploring

space is pointless and that ordinary people don’t care about the space program.

“Still-Life” is essentially written in the third person, though

at the end, after the climax, Malzberg pulls that gag in which the author admits the story is

fiction and the main character senses that he is a fictional character and confronts

his creator and author and character have a little philosophical convo.

The main character of "Still-Life" is an

astronaut and as the story begins he is a few days away from a mission on which he will be piloting a rocket from Earth into Lunar orbit; while he is orbiting the moon, two other astronauts will descend from the

rocket in a "module;" this is a practice mission, and the module will not actually land on Luna, just

approach it. (Malzberg is trying to make space exploration seem as tentative and unproductive as possible.) We get scenes in which

we witness how alienated the astronaut is from his comrades and his superiors

and his family; to me, the scenes with the family are more interesting that the scenes with his fellow astronauts and military men. The main character's wife doesn’t want to have sex; she thinks the space

program is a waste of time and energy; she has no respect for the stresses

and dangers her husband is facing—in fact, she thinks her job of managing the home and

trying to keep their two boys under control is much more challenging than

flying to the moon and back, even though her husband explains that on many

previous missions things have gone wrong and men in his position have had to exhibit

quick thinking to survive.

In the climax of the story, as we have been primed to expect,

the protagonist abandons his two colleagues, leaving them to die in the detached module, flying home in

the rocket without them.

I this story is good, even though I take Malzberg’s tragic view of

sexual life and family life much more seriously than I do his unwarranted skepticism

of mankind’s ability to accomplish great things and his somewhat tiresome fear of technology. One problem with the story is that the action of abandoning the two other astronauts isn't really all that closely linked to the main character's problems. If we think back to Malzberg's JFK story "All Assassins," which we read recently, we see that the protagonist f that story, JFK's appointment secretary, loses his mind and commits his crime--killing Kennedy--because he feels betrayed by Kennedy. It is insane, but it makes some logical sense. In "Still-Life" the main character's gripe is more with his family and the American public than with his fellow astronauts, or so it seems to me.

Another problem with "Still-Life" that applies to me and maybe not to other people is that I have already read several astronaut-goes-crazy-and-kills-people Malzberg stories, so it does not feel fresh; if this was the very

first Malzberg story I had read, no doubt it would have had a bigger impact on me.

|

| On the right, British edition |

“Yearbook” (1971)

This is a story about unrequited love and how our lives are

a meaningless jumble of events and we will never be satisfied with them. The narrator is a college student, attending

a protest because there are lots of hot girls there. The students are protesting policies that

limit their ability to drink and have sex in the dorms.

The narrator has a series of daydreams or visions or

whatever about what his life will be like in ten years, when he is married to some

woman who bores him. As a married man he

tries to engineer events that will fulfill the desires he had as a student,

like taking his wife, who is flabbergasted by such behavior, to the college make

out spot instead of just having sex with her in bed at home. While in bed or at

home with this boring wife he has dreams and fantasies of a woman he fell I love

with in college, but with whom he was totally unable to develop a relationship. But even in his fantasies the girl of his

dreams rejects his clumsy advances.

At the end of the story the protest has turned apocalyptic, with

the students burning down many campus buildings and dramatically murdering the Dean of Men

and the chancellor. Is this revolutionary violence really

happening, or just another dream, perhaps even a dream within a dream?

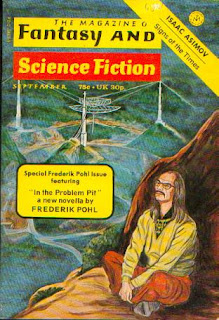

Acceptable. "Yearbook" debuted in F&SF.

"Inter Alia" (1972)

Handler is in an insane asylum. He was perhaps a Colonel in military intelligence, though that may merely be a delusion. He delusions that the Earth was visited by powerful aliens who wanted to disarm the United States, and that he was chosen to help them by pointing out the location of missile sites. He suspects that these aliens are not real, but a trick of the Soviet Union to disarm the US, but his efforts to protect America’s defense capabilities are not successful.

This one feels like mere filler—there is no poignant human relationship element, as there is in “Still-Life” and “Yearbook.” Maybe this is supposed to be a satire of “Cold War paranoia,” a catchphrase people who apparently think the Soviet Union was harmless or admirable throw around all the time. I'm giving the one-dimensional "Inter Alia," which first appeared in Infinity Three, a copy of which I own (I read the included Simak story some time ago), a thumbs down.

"The Helmet" (1973)

"The Helmet" has been something of a success, translated into several European languages and reprinted in an anthology edited by Poul and Karen Anderson after its debut in

F&SF.

Aliens have taken over Earth and they run it as some sort of dictatorship; humans are obligated to obey the orders of any alien who addresses them, no matter how arbitrary. Our narrator finds the aliens themselves and the new society they have built on Earth disgustingly ugly and depressing. The aliens provide him a helmet to wear around that affects his brain, making things appear less ugly to him and easing his unhappiness. But the helmet taxes his nervous system, and he has to take it off periodically to rest, at least until his body has become fully acclimated to it. But one day an alien scolds him for having the helmet off, not realizing or not caring about the prescription that he rest a few hours every day, and this alien issues a horrible punishment—the narrator may never wear the helmet again.

Like "Inter Alia," "The Helmet" feels like filler, but it is closer to being a fully developed story, with an actual plot with a beginning, middle and end, and with a human relationship subplot--the narrator has a friend, a guy who actually likes the circumscribed (but apparently comfortable in a cradle-to-grave welfare state way) world the aliens have constructed for mankind, and this guy tries to help our narrator, to his peril. Acceptable.

"Breaking In" (1972)

"Breaking In" has a central plot gimmick that bears some similarity to the one in "The Helmet." The narrator is a kind of emissary or diplomat or scout, alone in a city on an alien planet. His mission is to make contact with the natives and explain to them that they have to learn to love, to "care for one another," to "bind yourselves to the planet" and other hippie goop. I guess we are supposed to wonder if the narrator is a Terran on some other planet or if he is an alien come to Earth to tell us how to live--maybe we are supposed to think he is like Jesus...or like some European missionary in some colony, spreading Christianity. Whatever the case, whether we are supposed to sympathize with or deplore the narrator of this three-page story and his mission, he finds the natives so shocking that being among them threatens to drive him insane.

The natives in turn find him scary, and have little if any interest in his warnings. They capture him and pump him full of drugs; this treatment alters his mind, making the natives and their behavior appear normal, even beautiful to him--he is going to become one with them and abandon his mission.

I kind of like this one. "Breaking In" debuted in Fantastic.

**********

Well, I thought most of these were enjoyable. More stories from Out From Ganymede in our next episode!

No comments:

Post a Comment