I'm skipping the Laumer serial, because I haven't read the earlier novels in the series and my interest in Laumer is limited. I'm skipping Richard Lupoff's spoof of Harlan Ellison because spoofs have little appeal for me. And I'm skipping Barry Malzberg's "The New Rappacini" because I read it a year and a half ago; I called it "very good," so don't you skip it if you haven't read it yet!

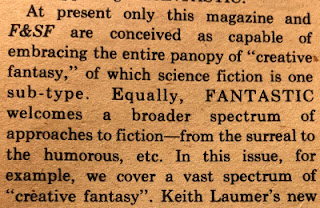

In his editorial, White talks a little about his relationships with the artists who have appeared in Amazing and Fantastic since he took over the role of editor, among them MPorcius fave Jeff Jones. He also quotes a letter from Ursula K. Le Guin praising himself and Fantastic, and explains what his policy is regarding the types of stories that will appear in Fantastic:

Yes, it sounds like he'll take anything.

Alexei Panshin's column, described as controversial on the cover, starts with a long quote from Damon Knight paraphrasing Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Then Panshin takes Kuhn's idea (that the scientific establishment fruitfully follows a paradigm for a long period, during which minor problems with the paradigm gradually accumulate, until those minor "anomalies" and "counterinstances" are numerous enough that the paradigm becomes weak and vulnerable to overthrow by a new paradigm) and applies it to the SF field. Panshin thinks the old SF paradigm is in a weakened state, and is under attack by the New Wave, but that the New Wavers have yet to come up with a truly new paradigm that is strong enough to replace the old. Panshin then describes his own writing career, in which (he says) he tried to write in new ways--he loved SF but didn't want to write melodramas or about technology--that were rejected by the SF establishment. But eventually he and his fellow young innovators, at first accepted only by Ace Books (which he calls "a rightly despised market that poured out such a stream of material that it would seemingly publish anything") fought their way to widespread acceptance, winning many Hugos and Nebulas. He then exhorts the SF community to continue changing and expanding, while admitting that there is still room for melodramatic stories about technology. Panshin suggests replacing the term "science fiction" with "creative fantasy," and throughout the magazine we can see White enthusiastically take up this coinage, using it in his editorial as well as in the intro to Malzberg's story.

Panshin's column is interesting, and as somebody who enjoys the old melodramas and sciencey stories as well as the work of many of the newer writers Panshin mentions, like Disch and Lafferty (and Panshin's own Rite Of Passage), I can look on these old controversies intellectually, with a comfortable level of detachment.

In this issue of Fantastic we find eleven pages devoted to letters and White's responses to them. There is arguing about drugs, overpopulation, the TV show The Prisoner, and, most heatedly, about ZIP codes and the Post Office (Ted worked briefly in the Baltimore Post Office, we learn.) I found most interesting the discussion of abortive attempts to include comic art in Galaxy (where Vaughn Bode's Sunspot appeared for four issues) and Fantastic (which included a four-page comic section called Fantastic Illustrated in at least one issue--the comic at the link is so lame it is embarrassing.) White claims that he was going to have Bode in Fantastic and then the deep pockets over at Galaxy stole Bode away with the promise of quadruple the amount of cash poor Ted could offer.

On to the stories! The Aldiss, Lafferty and Conway stories were new; the Swain is a reprint from a 1942 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

"Cardiac Arrest" by Brian Aldiss

This story (like 20 pages long) feels long and a little tedious. An American flies to Hong Kong under an assumed name in order to meet a business contact. On just about every page are italicized and ungrammatical stream of consciousness passages describing the Yank's fantasies and fears of violence and sex, daydreams and nightmares based on his reading of spy novels. (Aldiss throws in some poetic "wordplay," like combining Mao's name and the word "drowning" at the end of this aphoristic phrase: "the army and peasants are an ocean in which the invaders will drowsetung.")

Before his scheduled meeting, which is unexpectedly delayed, the American meets an Englishman, an RAF veteran of WWII and the Suez crisis, and this guy's German partner in grey and black market business ventures. The Yank explains that he is a scientist and he has brought with him samples of a virus which renders those it infects immortal--his idea is to defect to communist China and give them the virus; in return the Chinese Communist Party has offered him a big estate. The American gets involved in a sort of side deal with these two shady Europeans, whose help he suspects he needs.

The defection effort fails when Hong Kong police interrupt the American's meeting with a Red Chinese representative, and the German is killed. The American and Englishman flee for Europe, the RAF vet at the controls of a Soviet plane. Disaster strikes, and at the end of the story we learn the answer to the mystery that was nagging me for many pages: why would an intelligent educated American who was not a communist himself want to move to mainland China, which in the story is portrayed as a pretty menacing entity?

Along with the Walter Mitty/Owl Creek Bridge gimmick, Aldiss tries to do some interesting things in this story based around people's views of their own nations and other nations. Characters give voice to American and British attitudes about WWII, American views of China, England and Germany, European views of the USA and China (a subplot has to do with the Portuguese surrendering Macao to the communists) and Chinese views of America. Having fought in Burma in the Second World War, Aldiss has more first hand knowledge of the Far East than the average Anglophone bear--remember his story "Lambeth Blossom" about a tyrannical Chinese empire of the future? Another theme is that political leaders (and ordinary people as well!) the world over are hypocritical and untrustworthy jerks who may or may not believe the ideological stuff they say and whose actions may not accord with those stated beliefs..

I want to like "Cardiac Arrest" because immortality, exiles and emigres, socialist tyranny, and British military history are all interests of mine, but while it is inventive and experimental, it can be hard going. It is easier to admire the story now than it was to enjoy it when I was in the middle of it and finding it not very clear and not very compelling. I guess I'll say its virtues slightly outweigh the challenges it presents, and recommend it to people who like a story that is puzzling but which more or less puts all the pieces together by the time you get to the end of it. "Cardiac Arrest" would go on to be included on the DAW Book of Aldiss, behind an impressive Karel Thole cover and the British collection Comic Inferno.

"Walk of the Midnight Demon" by Gerard F. Conway

I don't think I have ever read anything by Conway before; he seems to be most famous for writing Spider-Man comics starting in the 1970s and TV crime shows starting in the 1980s. Along with the long list of comic books Conway has penned, Wikipedia offers a writing sample in which Conway complains about how difficult life is for the sons and daughters of Erin:

My grandparents were born in Ireland. They came to America in the late 'teens of the last century and lived a life not very different from the life my housekeeper and her husband live today.... Because they were lower-class Irish, they were the Hispanics of their day...viewed with scorn by the WASP upper class....Aye, Begorrah!

This story is set in one of those sword and sorcery worlds with witches and druids and people riding on horses and staying in inns and so forth. Our narrator is Haxx, and in the first scene he is riding across "the death plain" with his buddy Illusiah, who is dying of a stomach injury. After Illusiah expires and falls off his horse, Haxx subjects us to six or seven flashbacks which are presented out of chronological order. Haxx and his friends were cursed--as they traveled from inn to inn, everywhere they went people around them would turn up dead. They consulted various witches in an effort to find out what was going on, and we get a longish scene of a tarot reading. The whole story (like six pages) is boring; Conway tries to make it atmospheric with descriptions of faces and scenery and weather, but these descriptions made my eyes glaze over and the story is vague in every possible way. In the end we learn that Haxx is a vampire or werewolf or Mr. Hyde or servant of the "Death God" sent to gather souls or some such thing, that he has been killing all these people without any of his friends, or he himself, realizing it until it was too late.

Bad. "Walk of the Midnight Demon," a pointless exercise, has never appeared elsewhere.

"Been a Long, Long Time" by R. A . Lafferty

A tarot-reading woman figures prominently in T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land and in Conway's "Walk of the Midnight Demon," and Lafferty's "Been A Long, Long Time" begins with a direct reference to Eliot's "The Hollow Men": "It doesn't end with one--it Begins with a whimper." The whimper comes from Boshel, an immortal being at the beginning of time who, faced by a dispute between immortals--the rebellion of Lucifer that culminates in the Fall of the Rebel Angels--is unable to decide which side of the War in Heaven to join. By default, he ends up with the conservative forces headed by Michael, but Boshel's indecision leads to the introduction of randomness to the universe, and it is determined that he must be punished. Michael puts Boshel in charge of the practical realization of the famous thought experiment that insists that monkeys striking keys at random will eventually type out an exact text of the complete works of Shakespeare.

The immortal monkeys bang away at their unfailing typewriters for billions upon billions of years--the universe expands to its limit, collapses, and begins to expand again. This cyclical process repeats itself hundreds, thousands, millions of times! Boshel, and even more so the cleverest of the monkeys, grow frustrated, and that mischievous simian begins bending the rules a little in hopes of finishing up this absurd project once and for all.

This is a fun little story, and characteristic of Lafferty's work, with its folksy dialogue, entertaining jokes, and allusions to Christian thought. "Been a Long, Long Time" would go on to appear in Brian Aldiss's Galactic Empires anthology and The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy as well as two Lafferty collections, and has been translated into German, Dutch and Serbian.

"The Bottle Imp" by Dwight V. Swain (1942)

For whatever reason (and let's remember that when we read the August 1972 issue's letters column we learned that Ted's control of the magazine was surprisingly limited) the December 1970 issue of Fantastic includes a reprint of a story from the September 1942 issue of Fantastic Adventures, Dwight V. Swain's "The Bottle Imp." On the contents page it is hailed as a "Famous Fantastic Classic" but it is not even listed on the cover--maybe it was a last minute selection. I don't know that I have ever heard of Swain before; Wikipedia suggests he was an important teacher of screenwriters. In 1942 Fantastic Adventures published stories by better-known SF writers like Robert Bloch, August Derleth, Henry Kuttner, Eric Frank Russell, and Ross Rocklynne, and why they chose Swain over them is a little mysterious to me--maybe Fantastic had lost the rights to those stories, or maybe they were not the right length? Anyway, let's give Swain a chance.

Irish-American warehouse worker Tod Barnes is sitting in a crummy bar, lamenting his tragic lot and drinking whiskey and chewing Copenhagen (the kids we called "burnouts" in my high school used to chew that stuff) when a six-inch tall devil appears on his table! The satanic creature introduces himself as Beezlebub and Tod explains to his new friend that he has been laid off from his job at a tire wholesaler's but can't get a new job because the firm's owner won't give him a release (some kind of war-related regulation is involved) and he can't join the army because of a bum leg and his girlfriend Molly Shannahan has left him for middle-class guy Walter Dale (Tod calls him "one of those office lounge lizards...smooth line, all the trimmings.")

Beezlebub tells Tod that his problems are nothing compared to the trouble he could get him in, and proceeds to demonstrate. Tod vomits all over the new pants of another bar patron, mobster Steve Kroloski, renowned as "king of the rackets." A brawl ensues and Tod and Kroloski end up in jail. When Kroloski's lawyer springs him, the mobster also springs Tod. Tod is soon involved in the burglary of his old place of employment, the tire warehouse. Kroloski has Molly Shannahan kidnapped and dragged to the tire warehouse so she can open the combination locked door that stands between the gangster and the treasure trove of rubber. For good measure he tells her that Tod is a willing accomplice in this grand larceny.

Molly refuses to open the door, and Tod is forced to watch while Kroloski beats his former girlfriend until "even Molly's staunch Irish spirit could stand the torture no longer" and she relents. I guess the sons and daughters of the Emerald Isle really do have it tough! Beezlebub (whom only Tod can see, of course) takes credit for all the horrible things that are befalling Tod and gloats that Kroloski is going to murder both Tod and Molly to cover up his crime. Via an elaborate stratagem involving spitting and cutting his own flesh, Tod escapes his bonds, rescues Molly by throwing tires at the gangsters, alerts the police by spitting at burglar alarm wires, and exposes Walter Dale (one of those scornful WASPs, no doubt!) as Kroloski's inside man (the phrase "finger man" is used.) As the story ends Molly is back in Tod's arms, Tod gets a cushy government job ("warehouse inspector for the tire rationing board") and Beezelbub is exorcised in a dumb twist ending.

"The Bottle Imp" is a brutal (and somewhat disgusting) crime story full of torture and pain and tobacco juice spitting that exploits people's ethnic and class resentments and fascination with sexualized violence, upon which has been grafted a goofy devil story, I guess as a joke or a justification for printing a weak mystery story in a SF magazine--the imp is actually totally unnecessary to the plot and we are invited to assume it is simply an hallucination. Thumbs down for Swain, even if he is a member of the Oklahoma Writers Hall of Fame, along with R. A. Lafferty, C. J. Cherryh and S. E. Hinton. (On the upside, I guess this is an interesting historical artifact, a piece of popular fiction about the lives of American working-class civilians during WWII, written contemporaneously with the milieu it describes.)

**********

More stories from old magazines in the next installment of MPorcius Fiction Log!

The Conway story doesn't sound nearly as riveting as the original "Mindship" (1971) story I read. Rather, that sounds like bland sword and sorcery.... I wouldn't go of your way to find "Mindship" but, who knows, I might send you the novel version (with the short story which forms the prologue) eventually when I do another purge.

ReplyDeleteIt's been wonderful seeing you review volumes from the box I sent you!

I'm glad you liked the Lafferty story. I often use "Been a Long, Long Time" among a few other stories to show people who are scornful of SF what the genre is capable of.

ReplyDeleteAnd you have to admit, it has the best misquoting of a Shakespeare poem in the history of SF:

Delete"From this session interdict

Every fowl of tyrant wingg,

Save the eagle, feather'd kingg:

Damn machine the g is sticked."