|

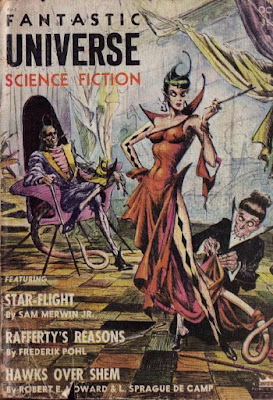

| Here we see two adventurers about to explore a mysterious alien city. The cover should probably depict a psychotherapist's couch. |

"Rafferty's Reasons" (1955)

Before the reforms of Mudgins, Rafferty was an artist. But after Mudgins was elected a strict policy of full employment was instituted by the government. To create more work the use of technology was severely limited--for example, the computers which controlled self-driving cars were made illegal to create jobs for taxi drivers. Artist Rafferty was put to work as an accountant at a public works Project, and he has to do all the math for payroll and everything else by hand, like he's Bob Cratchit or something!

Under the Mudgins regime people are actually compelled to work; working at the same office with Rafferty is a woman who would rather be a housewife and spend time with her kids. It is even suggested that, to maintain full employment, that surplus workers ("willfully unemployed") are simply executed--by the thousands! To maintain efficiency, now that computers are largely outlawed for productive use, computers are used to hypnotically train people like Rafferty; Rafferty is practically incapable of making a math mistake. This training can have damaging psychological effects, and in fact, Rafferty is dangerously insane.

This picture of Rafferty's world is slowly unveiled as the story (about 13 pages) unfolds. The plot concerns Rafferty's feverish desire and desperate plan to murder the head of the Project at which he is employed, an overweight man called John Girty. Rafferty talks to himself, a lot, mostly saying "I'll kill you, Girty" and calling Girty a cow or a pig; these silent mutterings appear multiple times on nine or ten of thr stor's pages. After work one Friday, Rafferty follows Girty to a Turkish bath and there tries to murder him, but what Rafferty thinks is a knife is an old cigar he found on the ground, so Girty survives the attack.

I'm not quite sure what Pohl is trying to tell us in this story; it feels like it is all over the place. The prohibitions on the use of machines and the forcing people to work (oh yeah, and the mass murders) are the work of the government, but this story is no defense of the free market against government intervention in the economy--even if we didn't already know Pohl is a socialist, his hostility to the free market is actually center stage in this story. The world depicted in "Rafferty's Reasons" has a two-tiered economy, in which people like Girty get paid in "real money" that can be used at "free market restaurants" and other private establishments (e.g., the Turkish bath), while people like Rafferty are paid in "Project-vouchers" that can only be used at places offering second-rate products, like government cafeterias. Maybe the story is a plea for government handouts of no-strings-attached cash instead of food stamps and housing subsidies and the like, benefits that everybody would be eligible to receive, regardless of their willingness or ability to work? A more interesting possibility relates to the productivity of machines--maybe Pohl thinks a world without work is possible with computers and machines, and is arguing here in "Rafferty's Reasons" that worries that such a world would lead to dangerous idleness or decadence are overblown and should not influence policymakers or voters. (It is sort of a common theme in SF stories that the easy life is unsatisfying or even somehow disastrous, and maybe Pohl is pushing back against that.*)

Another possibility is that Pohl is trying to dramatize the distinction between the ordinary man and the creative man. It seems like the Mudgins system is popular--it has won elections--so maybe Pohl is suggesting that ordinary people are fools, mere sheep who would embrace any crazy system, while superior people, sensitive creative people (like Pohl and the readers of Fantastic Universe, of course!) would crack under such a system.

Further confusing the issue, the Mudgins regime has, apparently, outlawed religion, free speech, even love--these prohibitions are just mentioned in passing and it feels like Pohl is just throwing into the mix every crummy thing a government might do, kitchen sink style, perhaps in an effort to appeal to every demographic. The anti-free market stuff might appeal to lefties, while having Mudgins crush religion and force housewives to work, and having Girty paraphrase a cliche associated with Stalin ("you can't make an omelette without breaking eggs") is maybe meant to appeal to conservatives? But the more crimes Pohl attributes to the Mudgins government, the less believable it is--who would vote for an anti-love regime?

|

| As my twitter followers know, I saw a copy of this recently |

Pohl writes a little intro to each story in In the Problem Pit but the intro here doesn't help us decipher the story's meaning. In fact the intro itself is sort of confusing, or at least witholds the sort of information we'd like to have. It seems Pohl sent "Rafferty's Reasons" to his favorite editor (unnamed) along with a second story (unspecified), and the editor bought that second story but not "Rafferty's Reasons," even though Pohl thought "R's R" was the better of the two. It was Leo Margulies, editor of Fantastic Universe, who bought "Rafferty's Reasons" and printed it; since then it has only reappeared in the Pohl collection Alternating Currents (1956) and this one.

*In the past I have exhorted my readers to not just accept second hand verdicts about the SF field but to investigate the primary sources, so here is some SF we've read here at MPorcius Fiction Log that features the "world-without-work makes people batty" theme: "Home is the Hunter" and "Two-Handed Engine" by Kuttner and Moore, Tanith Lee's Don't Bite the Sun, "The Miracle of the Lily" by Clare Winger Harris, "The Fence" by Clifford Simak. We also see the idea that mass unemployment leads to wacky and risky behavior in many Judge Dredd comic book stories.

"What To Do Until the Analyst Comes" (1956)

When it first appeared in Imagination this story was titled "Everybody's Happy But Me." Unlike "Rafferty's Reasons," "What To Do Until the Analyst Comes" was a hit, and has appeared in many anthologies of SF stories about drug use and psychology. In his intro to it here in In the Problem Pit, Pohl assures us he wrote it "quite a while before the hippies and the beats made dropping out a national conversational topic."

The narrator of the story works at an ad agency. When the government issues a warning about the ill health effects of smoking, the agency fears that business from its biggest account, a tobacco company, may dry up, so they cast about for another popular product that has no health issues. The narrator hires a chemist who comes up with a chewing gum that causes euphoria but isn't "habit-forming" or unhealthy. This product becomes so popular the efficiency of the world economy suffers because everybody is high all the time--newspapers appear with illegibly smeared pages, there is a radical increase in auto accidents, etc. The narrator sends out his secretary to get him coffee and she comes back with a Coke. (That is what qualifies as a joke in this story. The story's central joke is that the narrator can't chew the gum and be happy like everybody else--he's allergic due to overdosing in the testing phase.)

On the other hand, people are all so happy there is no more crime or mental illness (I guess in Pohl's 1956 story mental illness is not the result of chemical imbalances but "worry" and "hang ups") and a psychoanalyst tells the narrator that the gum has made the world a better place. I theorized that "Rafferty's Reasons" was a suggestion that we stop worrying about a world without work, and I am now theorizing that "What To Do Until the Analyst Comes" is a suggestion that we stop worrying about a world in which everybody is high. Together these stories seem to be an experiment in finding the limits of traditional morality--maybe it made sense to stigmatize idleness when almost everybody had to work hard or starve, and maybe it made sense to stigmatize drug use when drugs were poisonous and chemically addictive, but if we have machines to do the work and a drug that isn't poisonous or addictive, maybe those moral strictures need no longer apply, having outlived their usefulness.

"Conducting experiments in finding the limits of traditional morality" sounds like a worthwhile project, but unfortunately neither of these stories is a very good work of literature or entertainment; like "R's R," this story feels too long, and the jokes don't actually make you laugh. Another (moderate) thumbs down.

"The Man Who Ate the World" (1956)

Pohl's intro to this one is the insipid anecdote of how in 1948 he knew a five-year-old girl who combined the names of President Truman and his opponent Tom Dewey into the single name "Trummie." This is like the written equivalent of being forced to look at some grandmother's pictures of her grandkids.

"The Man Who Ate the World" is like 29 pages long and is split into seven little chapters. In Chapter I we meet Sonny. Sonny is eleven, and lives in a huge house where he is educated and looked after by robots. One robot looks and talks just like Long John Silver, another is Tarzan, and another is "Davey Crockett." (Maybe Pohl threw the extra "e" in there for legal reasons--about when this story was written Walt Disney had a popular Davy Crockett TV and merchandise thing going.) One robot is an obese black woman, Mammy, who says stuff like "Dat's nice when chilluns loves each other lak you an' that lil baby." Yes, Sonny has a little sister, Doris, and the point of this first chapter is that Sonny steals Doris's robot teddy bear! The end of the chapter gives us a clue to the point of this story when Sonny's flesh and blood parents appear. Sonny's family is low in status and are required by the Ration Board to consume tremendous resources--in this economy, which thanks to robots overproduces, low status families have an obligation to consume. His parents punish Sonny for wanting to consume a small teddy bear robot instead of a much larger Tarzan robot because by throwing him an additional birthday party.

Chapter II is like twenty years later--the underconsumption problem has been licked; robots now not only handle all the producing, but the consuming as well. (Are there people who enjoy these absurdist satires? For 29 pages?) We are introduced to a young "psychist," the futuristic word for "psychiatrist" or "psychoanalyst." The psychist has been called in to treat a man (later revealed to be Sonny) who grew up during the consumption era of twenty years ago--he was scarred by his pro-consumption childhood and is now a "compulsive consumer." Pohl is hitting us with not just one tired and boring fictional trope--the attack on consumerism--but a second one as well--the analyst who discovers the source of a character's mental problems in his childhood.

In Chapter III things get more absurd yet. Sonny (real name: Anderson Trumie) is a 400-pound adult who overeats and, in childish tantrums, orders his Davey Crockett robot to shoot his other robots (he has hundreds of robots and hundreds more to repair the hundreds that get shot) and cries and so forth. Chapters IV through VII describe in repetitious detail the psychist's investigation of Sonny's past, his journey to Sonny's island, where robots build model cities and play wargames, and his treatment of the compulsive consumer (he gets a girl to dress up as a teddy bear, which is what Sonny has always wanted!)

This story is quite bad. The ideas are tired, and instead of just inflicting them on us for four or five pages and then setting us free, Pohl hammers away at us for 29 damn pages. Fred, none of us is going to live forever! To fill up all these pages he repeats things; again and again we hear that the psychist is only 24 and worried if he has what it takes to cure Sonny Trumie, and we get multiple descriptions of how fat Trumie is and how disgusting are his eating habits. In Chapter II a minor character just says what Trumie's psychological problem is in a single paragraph, but then Chapter IV is devoted to laboriously and superfluously elaborating on Sonny's youth and compulsive consumption.

Beyond the first three (already weak) chapters, nothing in this story is interesting or amusing or entertaining. This story stinks.

"The Man Who Ate The World" was first printed in Galaxy. I guess people really did like it (who...are...these...people?), because it was the title story of a Pohl collection, included in an anthology edited by the wife of Pohl collaborator C. M. Kornbluth, and featured in a theme anthology with Asimov's name on it (the theme: sin.)

"To See Another Mountain" (1959)

"To See Another Mountain" was the only one of today's four stories to be included in the 2005 "Best of" collection, Platinum Pohl, a volume endorsed by a TV channel! (This same TV channel endorsed the nineteenth Dune novel, so you know they offer a seal of approval you can trust.) Maybe there is a chance this blog post won't go zero for four, as the sports lovers might say. The story first appeared in F&SF (in the same issue as "Flowers for Algernon," which showed up in one of my reading class textbooks in school) and soon after was printed in the collection Tomorrow Times Seven.

In his intro to the story Pohl tells us how much he loves Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto, which he saw performed at Carnegie Hall by Fritz Kreisler. He says he listened to David Oistrakh's LP of the Concerto repeatedly while he was writing "To See Another Mountain."

It is the middle of the 21st century. The greatest scientist of the last hundred years is Noah Sidorenko--Pohl compares him to Einstein more than once and all the major technology of the day is based on his discoveries. Today is his 95th birthday, and he is living in some kind of elaborate mental institution for geniuses, subject to screaming fits ("Stop! Stop!" he shrieks when President O'Connor comes by to give a speech on how awesome Sidorenko is) and prescribed drugs that cloud his memory because some horrible thing happened in his past that nobody wants him to remember.

The story includes a group therapy session, followed by the climactic scene in which Sidorenko sneaks through the institution at night (remember when a guy sneaked through a nursing home at night in Philip Jose Farmer's "The Henry Miller Dawn Patrol?"--that was fucked up, wasn't it?) and discovers that the other people in the group therapy session, all the other patients at the institution, are not patients but additional shrinks acting a part! He also learns what they have been keeping from him--he believes he has psychic powers! The shrinks all scoff at the idea of psychic powers, and have been trying to cure him of this delusion so he can get his super brain back on track making new important discoveries. Now that he realizes what is going on, Sidorenko is determined to escape the doctors' clutches and pursue the development of his mind reading and precognitive abilities--these super powers will be his true legacy!

This one has some real human feeling and a mystery that actually made me curious; I'm giving "To See Another Mountain" a mild recommendation, declaring it marginally good.

**********

All of these stories are about psychology; no doubt you'll remember that Pohl's greatest work, Gateway, also had lots of psychoanalysis in it, as did a story I thought was great, "The Fiend." But while those works are very successful, of today's four stories only one of them succeeds in presenting an interesting character or human relationship or any kind of human drama or adventure, and two of them don't even try. The three loser stories consist primarily of uninspired recitations of bottom of the barrel economic and psychological theories, and two of them are weighted down with painfully obvious and crappy jokes ("that dude is fat!...my secretary is high!...waka waka!")

In his introduction* to this volume, and a short essay at the end of it, Pohl provides us some possible clues as to why so many of these stories are so lame. In the brief essay, "SF: The Game Playing Literature," he talks about how SF is great for propaganda purposes and also for analyzing possible futures and alternate worlds; the "game" is tinkering with the "rules" of the physical or social or political world, the way you might tinker with the rules of Risk or Parcheesi, and playing out how these rule changes affect people's behavior and society. I agree with Pohl that this is a valuable aspect of SF, but if a writer focuses too much on this game-playing and not enough on traditional literary concerns he can end up producing some pretty boring or clumsy stories, which is, I suspect, what happened to three of today's four stories.

I think it will be a while before we read any more Fred Pohl here at MPorcius Fiction Log.

*This intro is dated "Red Bank, New Jersey, November 1974." In my last blog post I responded to learning of the existence of an anthology of "Florida science fiction" by wondering if there was an anthology of New Jersey science fiction--we can add Pohl to the list of possible contributors which so far includes Barry Malzberg!

Like any prolific author like Pohl, quality of his stories is going to be uneven. The 1950s was a "boom" time for Science Fiction digest magazines. It was easy for weak stories to get published then. By the 1960s, many of those SF magazines went out of business and better quality stories being published were the result. I consider Pohl a better novelist than a short story writer.

ReplyDeleteWhich of Pohl's novels do you consider the best? I guess Gateway would be the conventional answer, and it is certainly the one I have read which I think best, but are there any besides Gateway you might strongly recommend?

DeleteI just finished one of the stories you reviewed (to see another mountain) and and a similar reaction to you. The title story in this collection was the highlight for me, not so much as it being a good, cohesive story, but rather it had a couple of neat ideas in terms of societal changes.

ReplyDelete