We recently read

a story by Frank Belknap Long recommended by New Jersey native Robert Weinberg, author of

The Weird Tales Story (1977) and

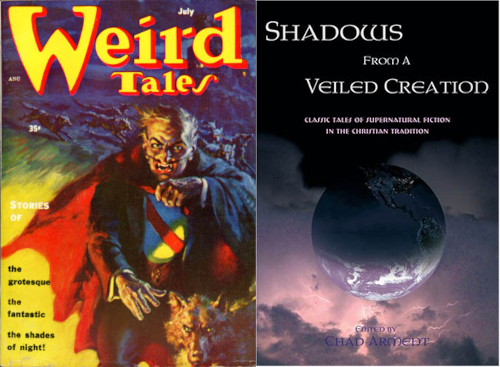

Horror of the 20th Century: An Illustrated History (1999). Weinberg, in those books, praises Henry S. Whitehead, another man who hails from the greatest state in the Union, but one who spent much of his life in the Caribbean. Whitehead published quite a volume of stories in

Weird Tales, and Weinberg picks out three for particular praise: "The Shadows," "The Fireplace," and "The Passing of a God." Today, through the magic of the internet archive, we'll read them and assess whether Whitehead, whom Weinberg deemed in 1999 to be a "neglected writer," deserves to be better known today.

I may be reading these stories in Weird Tales, but all three can be found in the 1944 Arkham House hardcover collection Jumbee and Other Uncanny Tales and its British 1974 edition, put out by Neville Spearman. For paperback publication our tea-guzzling pals over in the green and pleasant land split Jumbee and Other Uncanny Tales into two volumes; "The Passing of a God" and "The Shadows" appear in the first volume, Jumbee and Other Voodoo Tales, while "The Fireplace" is printed in the second, The Black Beast and Other Voodoo Tales.

"The Shadows" (1927)

This is a pretty effective story with a smooth understated style with quite a bit of local color about life in the West Indies for American and European residents. Our wealthy narrator, Stewart, an American, lives on a West Indian island in the house formerly occupied by an elderly Irish colonist, Morris, who died under mysterious circumstances. Stewart begins to experience a bizarre phenomena--when he turns off the light in his bedroom he can dimly see shadowy or ghostly images of different furniture than his own--presumably this is what the room looked like when Morris lived there. Each night, the images are sharper, clearer, and eventually Stewart can see Morris's furniture--in the dark--as clearly as he can see his own furniture in the light. Eventually he can see the image of Morris himself in the process of retiring for the night.

The second part of the story describes the narrator's detective work as he travels around the island talking to people and learning about his predecessor's strange life and mysterious death. It seems that, before moving to this island, Morris had truck with non-whites on another island and with one or more "jumbees;" "jumbee," a word I haven't encountered before, is apparently a term used in the West Indies to refer to a broad class of evil entities--spirits or ghosts or demons or whatever. People are reluctant to give our hero much information on Morris, and after, on a significant date, the narrator witnesses Morris's horrible death in the very room in which Stewart now sleeps, Stewart shocks his fellow expatriates with a dramatic revelation of his knowledge.

One might say this story moves slowly, but the style and images are good enough that it never becomes tiresome or boring. I enjoyed "The Shadows," and I think other Lovecraft fans might enjoy it as well, even though it is more light-hearted and the stakes feel much lower than in a Lovecraft story (Stewart is never in any kind of danger and is never really scared, being buoyed by his Christian faith), if only because it includes a pretty cool monster.

"The Shadows" after its debut in Weird Tales has been reprinted by such editors as August Derleth and Donald Wollheim as well as in Whitehead collections; in 2006 "The Shadows," as well as "The Passing of a God" and two additional Whitehead stories, was included in an anthology of supernatural stories written "in the Christian tradition"--Whitehead was an Episcopal minister.

"The Fireplace" (1925)

This is an OK ghost and murder story; while well-written, I am afraid there are too many nagging issues with the plot and structure of "The Fireplace" for me to call it good. Also, its locale is the American South, and the local color elements are not as interesting or effective as the West Indies stuff in "The Shadows."

The first little section of the story tells us that in 1922 a hotel in Mississippi burned down, killing four men prominent in politics and the law in MS, Georgia and Tennessee. Then we flash back a decade to the hotel and a young lawyer who is staying in the same room in which the four victims of the future fire will perish. The lawyer is surprised when a man inexplicably appears in the room--this man turns out to be a ghost. The ghost explains that sixteen years earlier he was murdered in this very room during a poker game, and the four men with whom he was playing--one of them his murderer--cut up his body and burned it in the fireplace and then hid his unburnable effects--cufflinks and such--under the floorboards. The ghost directs the lawyer to where these unburnables are concealed, proving his story true, and gets the lawyer to promise to pursue justice on the killer and his three accomplices.

The lawyer gets so busy with his career that he doesn't do anything to right the wrong supernaturally revealed to him and some time later he ends up in that hotel room again and he is found dead, strangled, his head in the fireplace.

On a sentence by sentence and paragraph by paragraph basis this story is well-written and it is never boring. However, there are problems with the plot and with some of Whitehead's narrative choices. I don't think you could really obliterate an adult human's bones in a 19th-century open fireplace, for one thing. Another problem is that we are to believe that the ghost strangled the lawyer who failed to help him, but earlier in the story the ghost said that he could only interact with the material world with great effort--"Managing to knock at the door took it out of me, rather...." Wouldn't strangling a healthy man and moving his body dramatically into the fireplace be far more strenuous an activity than knocking at a door? Another issue is that we don't get a scene of the ghost destroying the four men--how did he do it? I think we also have to wonder if four murderers would meet on the anniversary of their crime in the very spot in which they committed their crime (as in "The Shadows," dates and places are very significant in "The Fireplace," ghosts being very much connected to particular rooms and dates.)

Acceptable. "The Fireplace" was reprinted in Weird Tales in 1935 and since then in numerous anthologies of ghost stories, Perturbed Spirits (1954 hardcover, 1958 paperback) edited by R. C. Bull and Helen Hoke's Ghosts and Ghastlies (1976) among them.

"The Passing of a God" (1931)

Farnsworth Wright reprinted "The Passing of a God" in

Weird Tales in 1938 after its debut in the Unique Magazine seven years earlier, and Dorothy McIlwraith reprinted it in one of the last issues of the first run of

WT in 1954. In addition, the story has reappeared in several anthologies, including a Peter Haining volume of stories from

WT and the aforementioned book of ghost stories "in the Christian tradition,"

Shadows from a Veiled Creation.

Our narrator in "The Passing of a God" is an American living in the Virgin Islands and the story consists of his conversation with a Dr. Pelletier about a patient Pelletier treated while he was in Haiti, an American named Carswell. We learn the crazy life story of Carswell, presented somewhat out of chronological order so as to offer surprises to the reader. I'll just summarize the Carswell saga chronologically here.

Carswell, a man in his thirties, left New York when he learned he had a sort of tumor, about the size of a man's head, in his abdomen and was told he had only a year or so to live. He went to Haiti and made a sizable living shooting and drying ducks for export to the Chinatowns of New York and San Francisco. His tumor grew only slowly, and he survived year after year, putting together a nice house and becoming an integral part of the local black community; Carswell became very familiar with voodoo, and when Pelletier met him Carswell probably knew more about voodoo than any other white man.

Seven years after his arrival in Haiti, Carswell collapsed while walking home and woke up to find himself seated on a chair, surrounded by hundreds of blacks who were kneeling before him; Carswell's hands were weighed down with over one hundred rings and his neck strained under the weight of innumerable necklaces. Carswell recognized the phenomena of which he was the center. In Haiti, when a person, usually an elderly individual or someone mentally ill or developmentally disabled, as we now put it, throws a fit or goes visibly insane, the natives think he is possessed by a god and worship him; when he recovers his senses they feel the god has left and cease their worship. Carswell assured the "negroes" he was fine now, and they had no objection to him going about his business, but they continued to worship him.

Carswell left his remote home for Port au Prince soon after this event because his tumor, for the first time, was giving him pain. It was there that Dr. Pelletier met him. Seven years earlier the New York medicos had judged the tumor inoperable, but surgical techniques had advanced and Pelletier was willing to take a scalpel to Carswell, telling him he has a 40% or so chance of surviving the operation. The procedure was a success, and Pelletier removed the tumor. The tumor turned out to be an embryonic monster that emanated a chilling aura of ancient evil! Before the monster recovered from the anesthesia used on Carswell, the doctor drowned it in a specimen jar full of alcohol. Carswell returned to his work, and his black friends no longer worshipped him, recognizing that the god was gone.

Pelletier shows the monster to the narrator. The final twist is that Pelletier never told Carswell that his tumor was anything out of the ordinary--the white man who probably knows more about voodoo than anybody is ironically ignorant of the most salient fact of the most shocking of all voodoo incidents, even though he is the central figure of the incident.

Whitehead's style is smooth and his images are striking, and the plot proceeds without any hitches or hiccups--thumbs up for "The Passing of a God."

**********

Whitehead has a good mainstream literary style (like stories about white men out in the colonies among the natives so often do, the West Indian stories here remind me of Somerset Maugham) and all three of these stories work, the West Indian ones better than the American South one, which as far as I could tell could be set in any place in the world. While solid, these stories lack any special idiosyncratic personality or ideology, and come off as well-done but standard issue horror stories. I like today's three stories, but I don't know that I'll go out of my way to read more things by Whitehead when I have so many other authors I am more interested in, authors who have distinctive styles and/or peculiar concerns. We'll see.

No comments:

Post a Comment