Similarly, I wasn't necessarily crazy about the first few stories by R. A. Lafferty that I read, but I did get hooked, a process chronicled on social media, almost entirely on this blog. I read "The World as Will and Wallpaper" before the inauguration of my reign of error here, but wrote about the story in the comments at Joachim Boaz's blog in 2011, judging it one of the better pieces in the anthology Future City. In 2013 I read and blogged about "Narrow Valley," "For All the Poor Folks at Picketwire," "Nine Hundred Grandmothers," and "The Groaning Hinges of the World," and then started chopping away at the novels: The Devil is Dead, The Reefs of Earth, and Past Master. For ten years Lafferty was a regular presence at this here blog. In early 2023, I praised "And Name My Name" and "McGonigal's Worm" and then there followed a two-year Lafferty drought here at MPFL, broken just this week when we read "How They Gave it Back." Let's make sure my reading that story was no flash in the pan and begin a series of Lafferty posts today.

I own a copy of the 1973 DAW paperback edition of the 1972 Lafferty collection Strange Doings, and my aim is to exhaust the possibilities presented by this volume. I believe have already read five of the collection's sixteen stories, "Aloys," "Rainbird," "Once on Aranea," "The Ugly Sea," and "Incased in Ancient Rind." We'll read the remaining eleven over three posts, tackling four stories today, "Camels and Dromedaries, Clem," "Continued on Next Rock," "Sodom and Gomorrah, Texas," and "The Man with the Speckled Eyes."

"Camels and Dromedaries, Clem" (1967)

This is a fun little story that bears such hallmarks of Lafferty's work as humor based on violence and gore and direct references to the Bible. The story also perhaps raises issues of identity.A successful salesman, Clem, loses a tremendous amount of weight--like 100 pounds!--in the brief period of just a few days. Then he discovers that he has a double, a man who looks just like him, who shares many, though not all, of his memories and personality traits. Clem is out on the road when struck by this astonishing revelation, and decides to empty his bank accounts and take the money to New York City and lose himself among the masses, leaving his attractive and assertive wife Veronica behind with the other Clem. (He quickly returns to his normal weight.)

Years go by, and New Yorker Clem through various means follows the life and career of the Clem back home and the lovely and capable Veronica. Clem in the Big Apple meets other men who have suffered the bizarre fate of having been split into two, and is even exposed to theories that there is evidence in the New Testament of such phenomena having occurred in ancient times.

Clem's wife tracks him down--the Clem she is with is like half a man, not the man she married. Veronica puts her foot down--she wants the two Clems to reunite! Is this possible? Maybe if the Clems starve themselves, each lose 100 pounds, they will be rejoined into the full and complete Clem she loves? Or maybe Veronica should try to split into two? If she chows down and gains 100 pounds, maybe she'll split into two wives, rendering herself suitable for two husbands? I'm afraid I must report that a grisly and tragic ending awaits the desperate Clems and the bold Veronica.

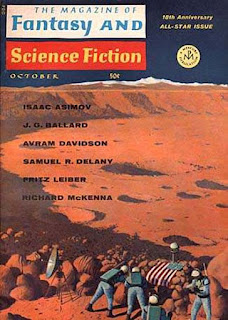

I like it. "Camels and Dromedaries, Clem" first fell under the eyes of readers in F&SF, and has reappeared in several places, both Lafferty collections and anthologies, including a volume of the long-running German series of "Best of F&SF" anthologies and a book of SF stories about weight edited by Isaac Asimov, George R. R. Martin and Martin H. Greenberg; a version of this latter anthology was published in Portuguese under the title Coma e emagreça com ficção científica. A Brazilian horror blogger reviewed this anthology and gave it ten skulls (caveiras) out of ten! If you can read Portuguese, you should check out that dude's blog--it looks pretty cool!

"Continued on Next Rock" (1970)

This one is kind of long and repetitive, and all the important plot points seem to be merely implied or indicated obliquely, making it a challenging read; I read "Continued on Next Rock" twice, trying to get a handle on it. I personally may have found it a little difficult to get a grip on "Continued on Next Rock" but it looks like it's a favorite of editors; after its debut in Orbit 7, Donald Wollheim and Terry Carr included it in their World's Best Science Fiction volume for 1971, it was reprinted in the 1971 Nebula award anthology, and you can also find it in The Best of R. A. Lafferty. Damon Knight selected "Continued on Next Rock" for his Best Stories from Orbit Volumes 1-10; I have read a bunch of Lafferty Orbit stories, among them "Dorg," "When All the Lands Pour Out Again," "Interurban Queen," "One at a Time," and "The Hole on the Corner" and I think I enjoyed all of them more than I did "Continued on Next Rock." (To be fair, Knight included two Lafferty stories in Best Stories from Orbit Volumes 1-10 and "The Hole on the Corner" was the other.) My preference is perhaps in part because, as I alluded earlier, my simple mind insists on remaining concerned with subject matter--if I see two paintings with equally good color and composition and technique, and one depicts a beautiful woman or handsome man, and the other depicts a landscape or abstract geometric shapes, I am going to gravitate towards the human being every time. The subject matter of "Continued on Next Rock" just doesn't grab me the way that of the other five Orbit stories mentioned above did.Alright, the plot, as far as I can understand it. Four fully credentialed academics and a female undergrad set up camp at an archaeological site; they plan to dig a vertical geological feature (a "chimney") and the ancient man-made mound beside it. Lafferty has named the undergrad Magdalen Mobley, maybe because Mary Magdalene was the first to find Christ's tomb to be empty? Magdalen is irascible, bossy, dismissive of others, and endowed with psychic powers and with super strength--one of the earliest episodes in the story has her spotting a deer on the other side of a hill and ordering one of the men to shoot it; she then carries the 190 pound carcass back to camp by herself to save the men the trouble of constructing a makeshift sledge upon which to drag it. Magdalen is not physically attractive, but all the men of the party desire her, and over the course of the story Magdalen rejects their advances with physical violence.

As if by magic, another man joins the group, an Indian who also has special powers, Anteros Manypenny. ("Anteros," Lafferty does not tell us until the last page of the story, is the name of a minor Greek deity, the brother of Eros--the wikipedia article on Anteros suggests he has a reputation for "avenging" victims of unrequited love.) Magdalen seems to know this guy; a philosophical discourse by one of the professors on the similarity of geologic strata and the human mind triggers her complaint that while the Earth is always changing, it is always the same people showing up, an early indication that Magdalen and Anteros are immortals who are always bumping into each other. Anteros can see artifacts in the rock before they are revealed, and dramatically demonstrates an ability to describe them precisely and predict exactly how many strokes of his digging tool it will take to unearth them. Magdalen, who is always criticizing Anteros and downplaying his accomplishments, implies that Anteros put these artifacts there in the first place.

The expedition discovers many unexpected artifacts, pottery and projectile points for example, that are anachronistically buried in chronologically inappropriate strata. By the end of the story the archaeologists are unearthing artifacts from the future. Among these mindboggling finds are rocks inscribed with love poems in rare and even never-before-seen languages that the language expert of the group nevertheless manages to decipher (though some of the others accuse him of just making the poetry up himself.)

The poems are among the numerous clues that suggest that for thousands of years Anteros has been courting Magdalen, trying to win her love by bragging about his riches (recall his surname, "Manypenny") and promising them to her and by writing these love poems. One of the verses ("Once again you will be broken at the foot of the cliff....") seems to refer to the story of Meles and Timagoras, which you can read about at the wikipedia page on Anteros; it and other clues suggest Magdalen has been, and perhaps still is, suicidal, and that she has been rejecting Anteros all these centuries because she is incapable of giving love.

In the end of the story Anteros has, apparently, been turned to stone and Magdalen has jumped off the chimney to her death. The four archaeologists' memories of these two otherworldly individuals and their astonishing feats quickly begin to fade.

This isn't a bad story, but I am not crazy about it, as I have already confided. There is quite a bit of Native American lore, a topic I am not particularly keen on. Every interesting incident happens three times (there are three stone-inscribed poems, Magdalen uses her special vision to spot prey animals three times, Magdalen violently rejects men's advances three times) so the story feels long and repetitive. And you have to really make an effort to figure it out, and when I'd thought I'd figured it out it didn't seem like a big deal. Most importantly, it is not as funny or as provocative as so many other Lafferty stories.

"Sodom and Gomorrah, Texas" (1962)

|

| Is that Christopher Lee over there? |

Thank you for fulfilling my request for more Lafferty reviews. I enjoy reading your reviews even when I don't agree with them, which is pretty often. "Continued on Next Rock" is my favorite story of this batch.

ReplyDeleteI, on the other hand, tend to agree with most of your reviews! And I experienced the same reaction to Jack Vance and Barry Malzberg and Lafferty that you did. Because they are very different from other writers, Vance and Malzberg and Lafferty require a period of adjustment before their intentions clarify.

ReplyDeleteThank you to both of you for reading my little blog and for contributing so many useful comments.

ReplyDeleteYou've already covered many of my favorite Lafferties. Here, for what it's worth, is my selection of the ones I don't think you've done yet. Novels: Space Chantey; Annals of Klepsis. Short fiction: Adam Had Three Brothers; Golden Gate; The Weirdest World; Long Teeth; Dream (a.k.a. Dreamworld); The Transcendent Tigers; All But the Words; Primary Education of the Camiroi; Polity and Custom of the Camiroi; Been a Long, Long Time; Cliffs That Laughed; The Ultimate Creature; Frog on the Mountain.

ReplyDelete