Today's blog post is brought to you by the letter "R." Yes, we're reading four more stories from Judith Merril's alphabetical list of honorable mentions at the back of the fourth of her critically-adored

SF: The Year's Greatest anthology series, the volume covering stories published in 1958. Today's authors are John T. Phillifent (working undercover as Arthur Rackham), Kit Reed, Mack Reynolds, and Charles W. Runyon. (I'd like to read the story by Joel Townsley Rogers that Merril recommends, "Night of Horror," but I can't find a scan of the issue of

Saturday Evening Post in which it appears.) With the exception of Reynolds, these are people I rarely read, so today is a day on which anything can happen. Let's just hope "R" stands for "really good."

"One-Eye" by "Arthur Rackham" (John T. Phillifent)

Already I'm questioning the itinerary our tour guide Judith Merril has prepared for us. When I read Phillifent's novel Genius Unlimited ten years ago I said, on this very blog, that

The writing is bad, one of the characters is silly and all the rest are without any personality, the jokes are bad, the action scenes are boring, much of the detective stuff and the science stuff feels perfunctory.

And yet, there is a glimmer of hope. When I read Phillifent's short story "Advantage" I liked it, and even defended it from the criticisms of influential blogger Joachim Boaz. Maybe "One-Eye," published in John W. Campbell Jr.'s Astounding, will emulate "Advantage" and win my admiration.

It is the future of hover cars. Tom Garbutt is a big muscular guy, a hover car mechanic with autism or a low IQ or a speech impediment or something, which is kind of annoying as much of this story consists of his halting dialogue and Phillifent's tortured descriptions of his thought processes. As the story begins, Garbutt is in jail. A shrink comes to talk to him. This smooth-talking smart guy is the first person ever to be kind to the hulking dimwitted mechanic, and for him Garbutt is willing to tell his tale of woe.

This morning Garbutt suddenly found that he could see accidents and tragedies in the future, but only a few seconds before they occur. Each of these prophetic visions is heralded by a terrible headache, then Garbutt sees his boss get injured on the job, or sees a cook slip and burn somebody with grease from the pan, or whatever. After the vision, Garbutt quickly tries to warn people, but there is no time, and the accidents still take place. Because of Garbutt's fruitless attempted interventions people begin to suspect Garbutt is somehow to blame for the misfortunes; his boss even fires him for being a jinx. (I guess jinxes aren't a protected class any more.) Garbutt has some more crazy adventures involving people being hurt or killed seconds after he had visions of the tragedy, and then he gets into a fight in a bar as part of his ill-conceived experiment to test whether he is himself causing the tragedies. (Maybe one of the things Campbell liked about this story is how Garbutt tries to use the scientific method to figure out the extent of his powers and his responsibilities for the disasters.) This fight is what landed him in jail.

After the shrink leaves, Garbutt has a vision of committing suicide and then he commits suicide.

This story is not a smooth read, and while the idea of a guy grappling with the unwelcome ability to see accidents and disasters seconds before they occur is sort of interesting, Phillifent doesn't really come up with a good plot based on this idea or a plot that exploits this idea. Phillifent doesn't substantially extrapolate on what this power could mean for an individual or a society and the mechanic doesn't do anything constructive with the power or overcome the challenge it presents--his life and then he are just destroyed by it in short order. I'm afraid the point of this story, the effect Phillifent seeks to have on readers, is to elicit sympathy for Tom Garbutt, a man who, because of his intellectual or physiological disability, is shunned by society and who then is overwhelmed by bizarre circumstance. (We smart readers of Astounding are expected to identify with the shrink, a compassionate man who uses his brains and knowledge to help others, so that he stands head and shoulders above the rest of society.) I'm not crazy about stories about helpless victims of fate or gentle giants who are abused by society, nor those in which nice liberals demonstrate their virtue by condescending to help their inferiors. Gotta give this one a thumbs down.

It looks like "One-Eye" has never been reprinted. Understandable.

"Devotion" by Kit Reed

College professor Kit Reed, according to wikipedia, is a Guggenheim Fellow and got a "five-year grant literary from the Abraham Woursell Foundation"--Kit Reed is the science fiction writer the intellectual elite in their ivory towers want you to read. Well, let's do what we are told by our betters for once and eat our vegetables.

We find "Devotion" in an issue of F&SF that includes a reprint of one of Leslie Charteris' The Saint stories, a Damon Knight short-short I bitterly denounced when I read it many moons ago, and Anthony Boucher's own backhanded smart-alecky denunciations of Robert E. Howard and Charles Eric Maine.

To the relief of all involved, I don't have to denounce Reed's "Devotion." (I know my kind-hearted readers don't flock to MPorcius Fiction Log lusting to read negative reviews--we're all softies, on the inside!) "Devotion" is actually a pretty good little story, creative and uninhibited by left-wing pieties (Reed includes an underhanded and jealous woman in the story as well as a vain and ridiculous man.)

Harry Farmer, all his life, has had a perfect and beautiful mouthful of teeth, the envy and/or wonder of all who see them. He maintains them with punctilious care, and he makes it to his seventies with them fully intact, no fillings, no blemishes on their dazzling whiteness. He loves the teeth more than anything, spending an inordinate amount of time admiring them in the mirror and showing them off to people.

At his Florida retirement home, Harry has a particular friend, almost a girlfriend, perhaps, a Mrs. Granstrom, who is his regular partner at shuffleboard and croquet. Mrs. Granstrom is very supportive when Harry faces the worst day in his life and is told by a doctor that he has to have his teeth all removed. She even provides him a beautiful velvet box in which to store and admire his--still perfect!--natural teeth like they are the family jewels or something. But she begins to get jealous when Harry starts spending less time at shuffleboard and croquet and more time in his room adoring--ne even caresses them!--his old teeth.

Harry's other problem is his replacement false teeth. They are animate and emotional, and express their jealousy towards Harry's old teeth, pinching Harry when he brags about the previous occupants of his mouth, moving around the room in an effort to get attention, etc. The clever ending of the story resolves both of Harry's issues--Mrs. Granstrom sneaks into Harry's room with a hammer, intent on smashing Harry's old teeth. Harry's new teeth attack her, preserving their rivals in a display of devotion that softens Harry's heart to them. Harry and his new fake teeth live happily ever after, the old teeth who abandoned him forgotten.

Thumbs up for "Devotion." The intellectual elite up in their ivory towers aren't always wrong.

"Devotion" has been reprinted a few times here and over in Europe, including in the Reed collection Mister Da V. and Other Stories. Joachim Boaz read the entire collection and blogged about it--check his assessments out! Oh yeah, and check out my middling review of Reed's story "The Visible Partner," which appeared in a 1980 issue of F&SF. If you are in the market for MPorcius negative reviews, at that same link you will find my long-winded explanation of why Harlan Ellison's story "All the Lies that Are My Life," the cover story of that same issue of F&SF, is no good and why Barry N. Malzberg, our hero, has all the virtues and none of the vices of the overrated Ellison. At MPorcius Fiction Log we court controversy!

"Pieces of the Game" by Mack Reynolds

I have

written quite a bit about committed leftist and

world traveler Mack Reynolds even though I think his writing is

poor, I guess because I find his

career fascinating and stupefying, and because his brand of left-wingery is unpredictable and defies easy categorization; he was thrown out of a hard core leftist organization because he was

not averse to bucking his masters and trying to make a buc behind their backs. Reynolds is more of a maverick adventurer type than a commissar or toady, and it is fun to reflect on the fact that famously right-wing John W. Campbell, Jr. published so many of his stories in

Astounding, Merril's 1958 pick "Pieces of the Game" among them. It looks like

Astounding is the only place it has ever appeared--Reynolds aficionados and collectors take note!

This story is so bland, so nondescript, and at the same time rather subtle and oblique, that I almost feel like I am missing something. As far as I can tell there is no twist ending, no character growth, no substantial or surprising ideological or philosophical point that Reynolds is trying to make. Maybe the point is to depict a future world in which international politics are cold and rational (you know, like chess) instead of ideological, with limited wars and little concern for human rights and forms of government--pure power politics, the pursuit of the national interest, with nobody caring about democracy or socialism or any of that jazz. References to the Hapsburgs are sort of giving me the idea that international conflict in the near future world depicted is modelled on the limited warfare of the 18th century, the period of the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War, wars often felt to be dispassionate and nonideological in comparison to the religious wars that preceded them and the ideological and nationalistic wars that followed them, wars in which elites at least pretended to be fighting for some sort of religious or political principle or for justice for their ethnic or cultural group.

"Pieces of the Game" is set in a future world in which the Soviet Union has apparently won a war, maybe a nuclear war, against the West, and even has military bases on the Moon, but the West does not seem to have been conquered entire nor its ;populations wiped out. Switzerland is still neutral, and the main character arrives in Switzerland, I guess from Britain or America, and makes his way into Austria, a "People's State" with lots of secret police--I guess Austria has been taken over directly or indirectly by the Soviet Union. I don't think the USA, USSR, or UK are ever specifically mentioned in the story, which is why I am guessing about all this stuff. Our protagonist is just five feet two inches tall, and it seems there are lots of diminutive people in this world, as well as deformed people and monstrously obese people, and these people are not regarded as freaks, but populate the elite--our guy attends a diplomatic function in Vienna and all the diplomats and dignitaries have one of these, to our minds, unusual body types. We have to assume they are mutants.

The main character is a sort of James Bondian super spy with lots of high tech equipment. He meets his contact, a doctor who injects him with a drug that gives him super strength, and then he spends several pages sneaking in and out of windows, climbing walls, swimming the Danube, breaking into offices, assassinating guards and cops and witnesses (well, maybe he just beats the witness unconscious), making a clandestine copy of some important document, and then sneaking back to Switzerland.

I guess we can call this odd thing merely acceptable.

"First Man in a Satellite" by Charles W. Runyon

Charles W. Runyon has four novels and 18 short story credits at isfdb. Apparently he is more famous for his stories and novels in the crime genre, though his true love was science fiction--

see this interview of Runyon by Ed Gorman. "First Man in a Satellite" was his first published SF story, and will be the first Runyon I have ever read. "First Man in a Satellite" appeared in

Super-Science Fiction after being rejected by Campbell--Runyon talks about Campbell's rejection letter in the linked interview above. Robert Silverberg included "First Man in a Satellite" in his anthology of stories from

Super-Science Fiction; it's a Campbell vs Merril and Silverberg throwdown--let's see who we side with!

The covers of Super-Science Fiction and of Runyon's novels (again, see the linked interview) are bubbling over with delicious sex and violence, and this story is absolutely about love and death, but it is more of a sentimental tearjerker than something sensationalistic and exploitative. Max is a dwarf and an acrobat. He's in love with the co-star of his act, Marie. They want to get married, and Max wishes he could set them up with some way to support themselves after they are too old to safely do their act. Then a solution falls right into his lap!

The government needs a dwarf who is in top physical condition for a top secret mission--to be the first man in space! A man his size weighs less, uses less food and oxygen, etc., an essential savings in this early phase of the space race, and his pay for three months work will set him up for life! The world must not know a human being is in the capsule, so Max can't tell Marie why he is leaving her for three months, which leads to her threatening to dump him.

After two and a half months of training, Max blasts off on his ten day mission, orbiting the Earth again and again while the many machines he is hooked into record his physical reactions and, when he is in line-of-sight radio range, the scientists interview him. Runyon focuses on Max's psychological stress while the operation is going as planned and then when a one-in-a-million piece of bad luck puts Max's life in jeopardy. A meteor pierces the sphere, and Max's air supply is diminished, so they have to try to bring him down earlier than scheduled. Uh oh, the remote control receiver on the jets is also down. Damn that meteor! The people on the ground go through a whole rigamarole, trying to direct Max in how to manually fire the jets at just the right time by exposing wires and stripping them and touching the right ones to each other at just the right moment but it is hopeless. When all hope is lost the world is apprised of Max's heroism and doom, and the story ends with Max and Marie spending Max's last hours talking over the radio, and Runyon's speculations on how knowledge of inevitable death affects a person.

This is a story about a man's psychology and relationships under stress, and Runyon does a pretty entertaining job of describing Max's struggles and his feelings about Marie, the head government shrink, and the military officer in charge of the whole operation. I couldn't tell if Max was going to make it or not, which was good. So I am siding with Merril and Silverberg over Campbell--"First Man in a Satellite" is a good story. In Campbell's defense, in his letter to Runyon rejecting the tale Campbell suggests Lester del Rey already did a story about a dwarf in space and maybe Runyon's was too similar to that earlier one to comfortably be included in the magazine.

**********

Well, of this batch, the Reed is the best and the Runyon is pretty good; Reynolds' story is lacking but it is not actually bad--the bad one is Phillifent's, which shares some of Reynolds' deficiencies and is also a drag to get through.

1958 stories from big names you'll recognize, but not necessarily titles you will be familiar with, in the next episode of MPorcius Fiction Log. We'll leave you with links to the earlier blog posts in our Merril-guided tour of 1958.

Poul Anderson and Alan Arkin

Pauline Ashwell, Don Berry and Robert Bloch

John Brunner, Algis Budrys and Arthur C. Clarke

"Helen Clarkson" (Helen McCoy), Mark Clifton, Mildred Clingerman and Theodore R. Cogswell

John Bernard Daley, Avram Davidson and Chan Davis

Gordon R. Dickson Charles Einstein, George P. Elliot, and Harlan Ellison

Charles G. Finney, Charles L. Fontenay, Donald Franson, and Charles E Fritch

Randall Garret and James E. Gunn Harry Harrison, Frank Herbert and Philip High

Shirley Jackson, Daniel Keyes and John Kippax

Damon Knight and C. M. Kornbluth

Fritz Leiber, Jack Lewis and Victoria Lincoln

Katherine MacLean, "T. H. Mathieu" (Les Cole) and Dean MacLaughlin A. E. Nourse

"Finn O'Donnevan" (Robert Sheckley) and Chad Oliver

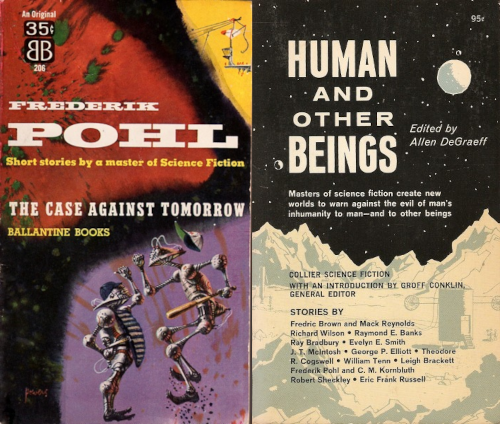

Avis Pabel, Frederik Pohl, and Robert Presslie