"The Omen" by Shirley Jackson

I generally avoid Shirley Jackson because mainstream critics are always breathlessly telling you how great she is so I assume they are overdoing it out of some ulterior motive, and because when people tell me about "The Lottery," a story they make schoolkids read, my only response can be "Is that it?" But today we'll read "The Omen" in an effort to see what all the fuss is about. For some reason Merril cites the source of the story as The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, Series 8, not the actual magazine issue in which it first appeared (the same issue of F&SF that printed Poul Anderson's "Backwardness" and reprinted Robert Bloch's "How Bug-Eyed Was My Monster," stories we read earlier this year) so I am dutifully reading "The Omen" in that anthology in case that version is updated or something."The Omen" is a cutesy humor story about a lovable grandmother and her adorable family and a nice young woman and her domineering, selfish, stifling, manipulative mother, so you know there is at least one realistic character is this story. There is however, in my humble opinion, no actual SF content in the story, just a long series of purportedly funny coincidences. What "The Omen" really is is a mundane mainstream story that looks at female relationships.

A sweet granny lives with her daughter, daughter's husband, and their two lovable kids. Granny falls into some money unexpectedly and decides to go out and buy everybody in the family a gift. She writes a vague shopping list which she loses on the bus the instant she sits down.

Then we have the pretty young woman who lives alone with her mother. She has a steady boyfriend who has wanted to marry her for three years--she hasn't consented because her monstrous mother refuses to give her blessing; Mom doesn't want to live alone and goes on and on about how she will starve if the daughter leaves. The attractive young lady has had it up to here with her mother and hurries out one day, exasperated, wishing she had the courage to disobey her mother and marry her guy. She wishes she would find an omen that would give her the strength to pursue her own life and build her own family. She gets on the wrong bus, finds the granny's cryptic list, and ends up in a part of town she has never been to before. She has a series of adventures that seem to correspond to the brief notes on the list she has found, and the upshot of these adventures is that she finds the willpower to call up her boyfriend at his work and say she will marry him and Mom will just have to live with it. These adventures involve encounters with other women and the highlight of these capers is her being mistaken for another woman.

Granny returns home with different gifts than her family asked for, but the kids still like their gifts.

I may be using the word "adventures" in describing Jackson's story here but this is not a thriller--"The Omen" is light-hearted and life-affirming, portraying no risk and no danger; for example, strangers all try to help granny--there are no Mike Tyson or George Floyd types in the story who try to rob her.

This is a competent, professionally put-together mainstream story that has very little provocative or surprising to say. Why F&SF editor Anthony Boucher and Judith Merril think it is a big deal--or an SF story--is a little mysterious, but I guess Boucher thought Jackson's name on the cover might move copies and Merril hoped some of the high status of a New Yorker writer would rub off on SF--Merril is famous for shoehorning stories by prestigious mainstream figures into her anthologies and for striving to convince people that SF is just as good as the mainstream and distinctions between genres are bogus and so on. Well, "The Omen" is not a bad story, so I guess I can't be too annoyed.

"The Trouble with Elmo" by Daniel Keyes

Like "The Lottery," "Flowers for Algernon" is one of those stories kids read in school--at least my class read it. Having put up my first blog entry about the famous Shirley Jackson today we are also posting my first ever blog content about the famous Daniel Keyes! It's a day of wonders!Here we have another humor story, but whereas Jackson's "The Omen" was more or less realistic and set in the mundane real world, Keyes' "The Trouble With Elmo" is broad and silly and an actual science fiction story about the future, technology and ideas.

The story begins with an obese Senator haranguing the world's top expert on the computer that is running the world, a man whose failure to deactivate the computer (nicknamed Elmo) has led to him being demoted all the way to private. Though a lowly private, our hero talks back to the senator, his unique skills being a sort of insurance policy, I guess.

Elmo was built and activated to solve a major world problem, but the solution the supercomputer instituted to that problem caused a new problem, and by solving that second problem Elmo triggered the arrival of a third problem, etc. This has been going on for years. The Senator is sure the computer is deliberately causing each of this succession of world-threatening problems in order to guarantee its own survival--after all, if Earth's problems are solved, Elmo will be deactivated.

Elmo solves the latest problem he has created by initiating first contact with space aliens and acquiring from them some valuable gas. In exchange, the aliens want the landmass of Asia--Earth can keep the people. Elmo foresees that Earth will need his services to manage the migration of the population of Asia to the rest of the world.

We get some run-of-the-mill political satire in the scenes of politicians in Washington responding to this deal. Then the private solves everybody's problems by convincing the aliens to accept Elmo and himself as payment instead of Asia. The private, in civilian life, was a fix-it man, and so likes the idea of solving the problems of alien civilizations in concert with Elmo, whom he considers a friend and is a good chess partner.

Lame filler.

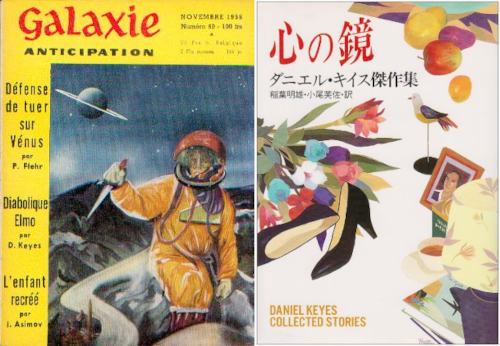

"The Trouble with Elmo" has not been reprinted in America as far as I can tell, though it was included in foreign editions of Galaxy and in a Japanese collection of Keyes stories. I am getting the impression that there has never been a Keyes collection printed in English, but maybe isfdb and wikipedia are steering me wrong (it wouldn't be the first time!)

"Me, Myself and I" by John Kippax

Well, here's another guy I've never blogged about before. Three excursions into virgin territory in one day! John Kippax is the pen name of British writer and musician John Charles Hynam and he has quite a few short fiction credits at isfdb. "Me, Myself and I" has a jokey title and I certainly hope it is not an absurdist humor story because it takes up 26 pages in the place I am reading it, Science Fantasy.Thankfully, this is not an over-the-top joke piece, and Kippax turns out to have a smooth comfortable style, so that, while the plot is just OK and the ending something of a letdown, the story never feels boring or long.

Gordon Beale is one of those middle-class guys who rides the train in to the office everyday to work. I was once one of those guys, though I lived in New York and Beale lives someplace in England and of course I was employed by the government so there wasn't really much work going on. Also, at home I had a steady girlfriend who became my wife (that's "partner" to you kids) and Beale has nobody and is quite lonely.

Beale is shy and standoffish and lacking in social skills so can't make friends or meet girls and spends his evenings alone at home--he's living alone but he neither likes it nor loves it. But then one day on the train he finds a book he assumes somebody left by mistake. He almost hands it over to the lost and found, but then he decides to take it home and read it. It turns out to be a self help book with no author's name on it and no publication data on any page. And like the note in Jackson's "The Omen," this strange document changes our protagonist's life--but this is a horror story so the change is not for the better!

The book encourages and guides Beale in an examination of his early life and uncovering of why he is a failure socially and then in the conception of a new version of himself that is a superior version of himself, similar but more bold, more assertive. Visualizing a better Beale makes a better Beale actually appear! A man who looks like Beale but is more confident, better able to focus and plan ahead, good at interacting with others, charming and persuasive. This new Beale is christened "Harry," and goes from being a faint image to a solidly real man! Gordon Beale starts staying home during the day while Harry Beale gets on the train and works in the office. On the train Harry makes friends with a neighbor who is able to offer valuable connections and stock market advice. At the office Harry bests Gordon's rival for the affections of a pretty young secretary (like 15 years younger than Gordon and Harry) and in the eyes of the boss, saving the company a stack of money by reexamining some figures. Gordon thinks that after Harry has secured a promotion and had sex with the secretary and gotten her to agree to marry him he can dematerialize Harry and enjoy the newly salubrious and happy life Harry has secured for him. But Harry has become too powerful to be dismissed! And when it turns out Harry has stolen money from the company to buy jewelry for the secretary, Gordon has to go on the lam, staying in crappy hotels and hiding from the police! But before the bobbies can drag him off to gaol with a "g," Gordon Beale keels over--Harry has found the book and has used it to create another Beale--Sam--and this has stretched the original's soul too thin. At least I think that is what happened.

This story gets a passing grade but there are serious holes in the plot. Where does the book come from? If the book was instrumental in creating Harry, how come Harry doesn't know about it and also falls into its trap? Gordon Beale is a fastidious rule-follower, bashful and lacking in initiative, so why does Harry turn into a brazen thief? And since the theft was discovered, doesn't Harry also lose his job and his girl? How does it help a now jobless and womanless Harry to create an additional duplicate who will also have to hide from the police? I'm afraid Kippax didn't put enough energy into coming up with an ending for his story.Besides the original magazine, you can find "Me, Myself and I" in a 2014 anthology of stories from Science Fantasy entitled The Daymakers.

**********

I don't consider any of today's stories good, but only Keyes' is actually bad. Jackson's is the best because, while Kippax also has a good style, Jackson's plot is internally consistent and her characters all act in a believable way, while Kippax's plot goes off the rails a bit at the end.

More Merril-approved "K" stories from 1958 when next we meet here at MPorcius Fiction Log.

No comments:

Post a Comment