Reading 1956 stories recommended by Judith Merril in the second edition of her famous anthology series was a good experience, so let's keep that ball rolling but shift to 1958 by using as our menu the three-page list of honorable mentions at the back of SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy: 4th Annual Volume. I'll pick out stories of interest from the list, three or four at a time, and we'll read and assess them, perhaps with an eye as to why Merril might have liked them.

The first name on the alphabetical list is Poul Anderson's, three of whose stories Merril recommends. I've already read one of them, "Last of the Deliverers," so to round out this blog post we'll read the included story by the second name on the list, famous actor Alan Arkin.

Before we begin our journey, I will note that, besides that list, two science articles, and a poem by Isaac Asimov, the fourth volume of Merril's much-heralded anthology includes 15 stories, of which I believe I have read nine; in one 2021 blogpost I talked about the included stories by Richard Gehman, Rog Phillips, Gerald Kersh and John Steinbeck, and in another the stories by Fritz Leiber, Brian Aldiss, E. C. Tubb, and Theodore Sturgeon, while back in 2019 I read the Avram Davidson story to which Merril gave the nod.

"Backwardness" by Poul Anderson

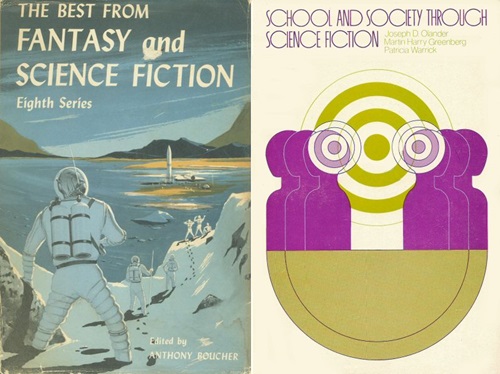

This story seems well-liked. Anthony Boucher, after publishing it in F&SF, included it in the eighth F&SF "Best of" volume, Martin H. Greenberg, Joseph D. Olander and Patricia Warrick selected it for their textbook School and Society Through Science Fiction, and Hank Davis included it in Worst Contact; the story has also been translated into French, Russian, Croatian and Japanese. Another place in which "Backwardness" appears is 1991's Kinship with the Stars, an Anderson collection I own, and I am reading it in there.Rats, here we have something of a joke story that tries to "subvert conventions," as the cool kids say. "Backwardness" is a first- contact-with-the-Galactic-Federation story. Anderson's tale is a series of vignettes, in which various Earthmen of the nearish future interact with the representatives of the GF, who have arrived because they detected the first use of an Earth star-drive. The GF, which has been around forever and includes thousands of planets, investigates all civilizations that are on the brink of exploring the stars; violent civilizations are exterminated forthwith, but luckily Earth passed the test.

I suppose it is common for SF stories about aliens who arrive on a pre-FTL drive Earth to portray the visitors as wise or cultured or super-intelligent or something. Anderson's joke is to suggest that the people of the Galactic Federation--or at least these representatives--are unsophisticated rubes of average or even below average intelligence, by Earth standards; the Galactics have outstripped the people of Earth technologically simply because they have had so much longer to develop.

Anderson explicitly lays out his premise on the last page of the 12-page story; the preceding pages illustrate it. A party of the GF spacemen paints the town red in Manhattan, getting drunk, banging sluts and buying and adorning themselves with cheap garish jewelry. (All the aliens in the story look like Earth humans--the galaxy is full of human civilizations.) The head of the UN meets the captain of the GF ship and finds the alien can't explain anything at all about science or technology and that the GF has a quite laissez faire government--the alien captain, who has been to many planets, remarks that New York City is the biggest city he has ever seen and marvels at the ability of Earthers to govern such a huge conglomeration of people. A Catholic bishop meets the alien vessel's chaplain, expecting to be enlightened by a sophisticated thinker, a theologian, only to learn this guy is addicted to TV ("You got some real good TV on this planet") and that the religion of the ship's crew consists of sacrificing cows (rabbits on a ship, to save space) to appease the gods and bring good luck. (Alien planets don't just give rise to intelligent beings genetically similar to Earth people--the plants and animals there are also the same as Earth's.) Anderson's big concluding joke is that a New York con man with a bachelor's degree in psychology quickly susses out the aliens and sells one of them the Brooklyn Bridge.

As joke stories that try to subvert conventions go, this one isn't bad. The jokes are not annoyingly lame, and the idea that an intelligent species with an average IQ of 75 instead of 100 would eventually build nuclear reactors and space craft, it would just take longer than it has take us, is sort of interesting, So I'll call "Backwardness" acceptable.

"People Soup" by Alan Arkin

Alan Arkin is a beloved actor with a stack of awards but I have to admit that I find his face and his voice annoying and so as an adult I have not sat through any of his films or TV shows. (As a kid I saw on TV The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming and The In-Laws because my mother liked them, and it is possible my distaste for Arkin is a subconscious act of rebellion.) But maybe I'll like this story, one of three short stories with which Arkin is credited on isfdb."People Soup" is a trifle about precocious kids; it is five pages of obvious but inoffensive jokes.

Bob slopped a cupful of ketchup into the juicer, added a can of powdered mustard, a drop of milk, six aspirin, and a piece of chewing gum, being careful to spill a part of each package used.

(I realize that I type the phrase "obvious jokes" often, and begin to fear that at age 52 I have heard all the jokes I am going to hear and so now all jokes are obvious to me.)

Mom is out shopping, so little Bob mixes ingredients apparently at random, puts the concoction in a pot and cooks it; he lets his sister Connie help after she pays him ten cents. They taste the finished product and pretend to have turned into animals. Then they pretend to have turned back and go out for ice cream.

To me, it feels like an acceptable filler story, but Merril isn't the only person to take "People Soup" seriously. Groff Conklin included it in the anthology Science Fiction Oddities, and another pair of anthologists whose names I am always typing out, Martin H. Greenberg and Joseph D. Olander (with the participation of Fred Pohl) included it in the 1980 anthology celebrating Galaxy. Arkin's name doesn't appear on the cover of any of these publications, so I can't say these editors and publishers are using Arkin's famous name in an effort to win attention from beyond the ranks of SF fans. Perhaps we are supposed to think this cutesy story has an edge. The way the text reads, the reader is permitted to believe the kids actually do change into a chicken (Connie) and then a St. Bernard (Bob) and then back. Connie doesn't like being a chicken, but Bob urges her to remain one as long as possible in order to collect information about chicken life. In the last lines of the story, Bob declares his intention to build an atomic bomb tomorrow. Maybe Arkin is suggesting that the search for knowledge in the late 1950s is being conducted by reckless men who blithely take terrible risks with the lives of others. The title of the story, after all, sounds a little grisly.

**********

None of these stories is bad, so we can say without reservation that the first step on our journey through 1958 with Judith Merril has been an easy one.

Keep an eye out for future installments of this series on 1958 SF stories; next time, however, we'll be looking at stories from earlier decades.

No comments:

Post a Comment