We are witnessing the end of an era! For a year we here at MPorcius Fiction Log have been reading stories published in 1956 that appear on the Honorable Mention list at the end of Judith Merril's SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy: Second Annual Volume. This list is alphabetical, and we started with A, and through 18 blog posts we have read something like 60 stories and made our way all the way to W, the final letter on the list (I guess Merril didn't like any of Robert F. Young's 1956 stories, and it doesn't look like Roger Zelazny published any stories in 1956.) And today we have post number 19 and a final three stories, one by Robert Moore Williams and two by Richard Wilson. (I wanted to read Anthony G. Williamson's "To Reach the Stars," but I can't find a scan of Authentic Science Fiction's May 1956 issue.)

"Sudden Lake" by Robert Moore Williams

"The Big Fix!" by Richard Wilson

Back in 2016, I read Wilson's Nebula-nominated 42-page story "The Story Writer" and condemned it as "sappy, sentimental, self-indulgent and pandering," called the plot "absurd, banal and tired" and denounced the style as "long-winded and boring." And yet today I choose to grapple with Wilson's prose not once, but twice!Round One! "The Big Fix!"

Our narrator is a man who "has been mainlining it for a decade" but has been "off the junk for three months," having had enough of the life of poverty and violence that is the lot of the junkie; to satisfy his needs he has been relying on mass quantities of alcohol. As the story begins, he is pursuing rumors of a new drug that isn't habit-forming and which can induce what I'd call collective consciousness ("open up the world for you so you'd be close, really close, to others like you....your mind would be their mind....union more terrific than any other kind....") His quest leads him to a Manhattan apartment where a mysterious dealer has him lay down and smoke a weird cigarette in a weird holder.

The narrator is transported to an extragalactic planet where there is no pollution or machinery and people share their thoughts telepathically and relax and eat delicious food in cities of short quaint buildings, not impersonal oppressive skyscrapers. (Come on, Wilson, I love skyscrapers!) But our narrator's visit is a brief one--if he wants to return to utopian Uru, he will have to sign up permanently, abandoning Earth forever. And he does!

Flash forward to the narrator's life on Uru--like so many people in SF, he has been thrown into the gladiatorial arena! The former junkie participates in battles between teams of fifteen men, all wearing gloves and boots studded with steel claws and even mouthpieces with fangs! The drug dealer who recruited the narrator, a native of Uru, is commander of the team, directing his fifteen men via telepathy from outside the arena. These annual games resolve disputes between cities, and serve as a cathartic "letting-off of steam" for the natives of Uru, who through their telepathy can experience the emotions of the 30 gladiators shanghaied from all over the universe without themselves risking life and limb. This is his third and final fight; if the narrator, who has already lost a leg and an eye in his first two engagements, can live through this one he will be awarded a place in the aristocracy.

The fights are not free-for-alls, but a series of one-on-one duels. By coincidence, today the narrator is faced with a fellow Earthman. When the combatants realize they are both human (people from all over the universe look the same, it turns out) they refuse to fight, and so are sent back to Earth. On Earth these two wangle positions on teams conducting research on peyote--our happy ending is that the narrator has figured out a way to get paid to use drugs.

"The Big Fix!" is well-written, especially the first two-thirds on Earth, but I'm not sure the whole thing holds together well. Are we supposed to see some parallel between recreational drug use and vicarious enjoyment of violence? If we are, Wilson doesn't sell the parallel very well. If we aren't, "The Big Fix!" feels like Wilson just jamming together three different SF themes (mind-expanding drug use, the dark underside of utopia, and being forced into the arena) that don't really sync up well.

After the narrator abandons Earth the whole story feels discordant and disconnected, even if we ignore the nuttiness of the idea that smoking a cigarette can transport your physical body to another galaxy in the blink of an eye. How are we supposed to think about the people of Uru? Is Uru really a paradise if they trick foreigners into losing their lives in the arena? And if they are ruthless enough to fool people into becoming gladiators who are likely to die, does it make sense they are generous enough to send recalcitrant gladiators back home? The ending, in which the druggies find an ostensibly healthy way to devote their lives to recreational drug use, is not very satisfying--a more satisfying ending would be punishment for throwing your life away on drugs, or some kind of redemptive ending in which the druggies go straight. The ending we get, in which the druggies keep using drugs and are even paid to do so, feels like a cop out. Is this story just a roundabout endorsement of peyote?

I'm going to call this story acceptable; before the gladiator stuff started I was expecting to give it a thumbs up. "The Big Fix!" will be of value to those interested in depictions of the drug culture, and might also be seen an example of the romanticization of Native Americans, as the narrator closely associates peyote with Indians. Also of note are references to Aldous Huxley, whose book on his use of mescaline (the active agent of peyote), The Doors of Perception, came out in 1954.

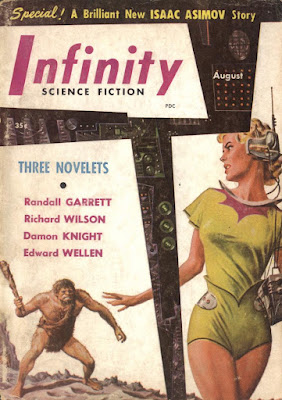

"The Big Fix" first appeared in Infinity, in an issue we looked into in June of last year when we read another story promoted by Merril, Randall Garrett's "Stroke of Genius." "The Big Fix" would be reprinted in an anthology of stories about drug use edited by Michel Parry called Strange Ecstasies and in the Wilson collection Time Out for Tomorrow, which in both its American and German printings has enjoyed some pretty awesome covers.

"Lonely Road" by Richard WilsonRound Two! "Lonely Road."

This is a sort of Twilight Zone-style story. Our main character is on a long drive homewards. He realizes that he has seen no other cars on the road for some time; he goes into restaurants and gas stations and finds no people around. We get several pages of him trying to find evidence of people, leaving money in empty businesses so he can feel comfortable about taking the food and fuel he requires. We also learn in passing that his young son died recently.

He's almost home when he starts seeing people again. Everybody is acting a little strangely, and when he asks about the last two days, the days when he seemed alone in the world, they don't have much to say, sort of avoid the topic. Back home with his wife we get some clues as to what happened. For one thing, at the approximate times her husband stopped seeing people, and started seeing them again, his wife noticed some pretty odd phenomena. More significantly, we hear about one of their son's last activities.

You see, their boy, when his illness got too severe for him to get up and around much, seriously took up tropical fish as a hobby. He even had his parents buy a second tank and, as an experiment, transferred the fish from their original tank to the second tank, which was arranged a little differently. Eventually he realized that one of the tank's denizens, a snail, had accidentally been left behind in the first tank. Then he put all the fish back into the first tank. Wilson gives us reason to believe that God or Fate or whoever or whatever moved the human race to a quite similar Earth--leaving the protagonist behind by mistake--and then after two days moved all the people back again.

This story is reasonably well-written, and all the stuff about grieving parents makes you a little verklempt, but what is the point of the weird SF element? The boy died soon after his abortive experiment, and the fish all died soon after that--are we to believe that God or the Universe and/or the Earth and its inhabitants are on the brink of death?

Wilson's depiction of a man left totally alone and of parents' heartbreak are pretty effective, so I'm willing to call "Lonely Road" good. "Lonely Road" made its debut in F&SF, in an issue which features Reginald Bretnor's "The Past and its Dead People," a particular fave of Merril's, and a reprint of Evelyn E. Smith's joke story about people who design crossword puzzles, "BAXBR/DAXBR." "Lonely Road" was a success, being reprinted in the Wilson collection Those Idiots from Earth and numerous anthologies, including John Pelan's The Century's Best Horror Fiction 1951-2000.

The Wilson story I hated appeared quite late in Wilson's career, and maybe represents a decadent phase of his writing; perhaps I should try to find these paperback collections with the terrific Richard Powers covers and sample more of Wilson's 1950s work.

No comments:

Post a Comment