Let's visit the late 1970s, when MPorcius was still skinny and still thought girls were icky! Today five stories from Barry N. Malzberg's 1980 hardcover collection The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady will fall under our gimlet eyes ("gimlet," "rheumy," choose whatever cliche you feel appropriate.) We're like halfway through this volume, having already wrestled with about a dozen stories from it over the course of three blogposts (one, two, three.)

"On Account of Darkness" with Bill Pronzini (1977)

This story serves as the title piece of a 2004 volume of Malzberg-Pronzini collaborations, a book I actually held in my hands when I was living in Iowa and exploring the SF section of the Des Moines Public Library. I read the short story "On Account of Darkness" in those pre-MPorcius Fiction Log days, and thought it a piffling trifle; let's see what I think today.Before the internet age I paid a lot of attention to the mass media--every morning I listened to Howard Stern and every evening I watched Johnny Carson, David Letterman and/or Conan O'Brien, and to get all their jokes and references you sort of had to watch the nightly news and prime time TV. (In my defense, I didn't sit and stare at the screen unless Dana Delany or Isabella Rossellini was on; I played video games or painted Warhammer 40,000 models or looked at books about Horatio Nelson or something.) One of the odd topics that would come up on local public service commercials and the local news was musicians or artists moaning that kids today didn't get enough exposure to jazz or classical music or painting or whatever at school, that we had to increase public funding for arts programs. I always rolled my eyes at this stuff (people under the influence of Howard Stern and David Letterman during the period when they were actually funny rolled their eyes at everything) because why should I care that some other guy's hobby was going extinct--why should the taxpayers pony up to ease your worries that your favorite thing was no longer going to be popular after you were dead?

Anyway, "On Account of Darkness" exhibits this no-doubt heartfelt attitude I found silly, Malzberg and Pronzini lamenting that some day one of their hobbies--following professional baseball--would be extinct. The story also seems to reflect the experience of creative people compelled to supplicate before business people or other funders to achieve their visions; a lot of people who want to make a TV show or a movie or a record album or paint or sculpt have to make a "pitch" to some network or film studio exec or some government flunky or non-profit parasite who hands out grants (and of course Malzberg and Pronzini were often in the somewhat analogous position as writers submitting the stories and ideas to editors and publishers), and this sort of thing is what the protagonist of "On Account of Darkness" does. Needless to say, artistic people think business people and government flunkies and non-profit goofs are ignorant jerks, and sometimes they are right.

I seemed to see myself in ten other offices like Evers', past and present, at the mercy of people like him who understood very little and yet, somehow, controlled everything....*It is the future. The protagonist has invented what we might today call a simulator or sandbox video game that recreates 20th-century baseball games in miniature and can project a holographic image of the game of life-size or smaller. He goes into the office of a guy called Evers to get financing for mass producing the invention or maybe sell the rights to hold public performances of the simulated games. He demonstrates its use, and talks a lot about baseball players, some of whom even I have heard of. Evers, however, has never even heard of baseball before, and our hero is only able to get a pretty meagre offer, which he accepts grudgingly. The last line of the story indicates that he has similar devices that simulate hockey, basketball, and horse racing, calling into question whether he is as passionate about baseball as he professes to be, or just another business man with a product to sell.

This story is minor and parochial, aimed at people just like Malzberg and Pronzini, but it is actually well constructed and the style is not as opaque as so many Malzberg stories. When I first read it years ago, I thought, "Is that it?" but today I read with a little more care and thought, and can give "On Account of Darkness" a moderate recommendation. Like A. E. van Vogt says, science fiction requires a little work on the part of the reader, and today I was willing to put a more work into "On Account of Darkness" than I was in the past, and consequently I got more out of it.

"On Account of Darkness" made its debut in F&SF. In his afterword to the story here in The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady, Malzberg suggests he sent the story to Ben Bova at Analog and doesn't know why Bova rejected it, and claims it is as good a story as he has ever written and in fact his best collaboration with Pronzini. The tale has been reprinted in multiple anthologies of baseball stories, another volume of Malzberg collabs with Pronzini--Problems Solved--as well as the 650-page Greenberg, Waugh and Waugh 101 Science Fiction Stories AKA The Giant Book of Science Fiction Stories.

*There was no apostrophe after "Evers" in the magazine version of the story, or in the version of the story here in The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady, but I finally looked at the version in Problems Solved and found an apostrophe there, so bravo to whoever had a hand in putting that much needed bit of punctuation in there so I didn't have to put that "[sic]" thing in the quote.

"Impasse" (1976)

"Impasse" first saw print in the issue of the short-lived magazine Odyssey we looked at not long ago alongside stories by Jerry Pournelle, Fred Saberhagen, Thomas N. Scortia and Frederik Pohl. It looks like it has only ever been reprinted here in The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady.I like it when SF writers refer to the "real" writers I like, and in this story Malzberg refers to Proust and presents us a narrator who is holed up in his room writing a long memoir with a focus on sex, somewhat like Proust writing his semi-autobiographical novel In Search of Lost Time. This narrator is a graduate student in Political Science at Columbia, and is stuck in his New York apartment because his apartment has been conquered by aliens--his apartment is the beachhead of a general invasion of Earth that could come at any minute. The aliens are furry, the size and shape of golf balls, and speak English with an accent; they have forbidden the student from attending class, and demand he write his memoir, as they want some documentary record of life on Earth before their conquest. Besides, political science will be a totally useless discipline after the aliens take over Earth, as the aliens will have total control and, being a corporate entity with a collective consciousness, have no politics.

The narrator comes to believe that the aliens like--even love--his prose (they sit on his shoulders and on his typewriter and desk and read his writing as he types) and that he can save the Earth from invasion by keeping their attention on his writing--as long as they are fascinated by his memoir, they will leave the rest of the human race alone.

Obviously, the narrator is insane and has come up with a fantasy that excuses, even valorizes, his desire to shelter in his room, away from his unrewarding studies and his unsuccessful relationships, and do what he really wants to do--write his memoir.This is a good story with themes (wanting to hide from the world, wanting to quit school and give up on relationships with other people, the fantasy of having one's creative work admired) I can identify with; it is also very recognizably a Malzbergian tale--our hero Barry has penned other stories in which insane men think they have been contacted by aliens and have to try to save the world by just doing mundane stuff like playing chess (see 1973's "Closed Sicilian") or making progress at their office jobs (see 1974's The Day of the Burning.)

In the afterword to "Impasse," Malzberg writes a little about Odyssey and George Zebrowski--you know I enjoy this sort of SF inside goissip.

"Varieties of Technological Experience" (1978)

Here's a story that Ben Bova did buy for Analog, a gimmicky little story about a scientist. The corrupt authoritarian government of a Federation apparently encompassing the Solar System imprisons allegedly dissident scientists on a moon of Neptune, providing each laboratory facilities and saying he will be given his freedom if he can accomplish some specific and apparently impossible task. One scientist decades ago was given the job of creating a perpetual motion machine, for example. The protagonist of this story is assigned the task of creating a universal solvent.The main character actually succeeds in creating a universal solvent--it destroys the entire moon and everybody on it. At the end of the story we learn that the Federation has since been overthrown but it is hinted that the new government is also authoritarian.

Merely acceptable, though it is interesting to see that one of Malzberg's few stories to appear in Analog has the basic structure as well as some of the themes of the sorts of stories that appeared in the magazine when John W. Campbell, Jr. was editing it (van Vogt's Isher stories are a good example) like the scientist who breaks new ground and the space empire that goes through a paradigm shift.

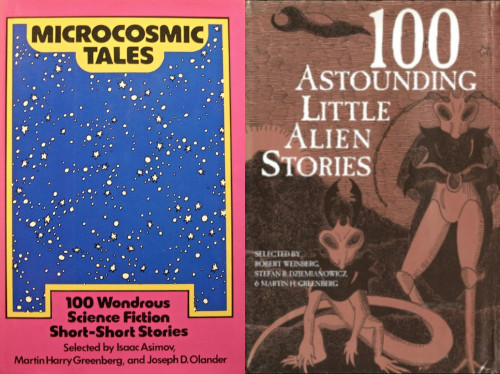

"Varieties of Technological Experience" would be reprinted in two anthologies of short-shorts, Microcosmic Tales and 100 Little Astounding Alien Stories; wait, are the scientists and Federation apparatchiks not human?

"Varieties of Religious Experience" (1979)

This is the first person narrative of a minor (very minor--it is implied he has a communications degree) writer of literary stories and denizen of the non-profit world who took up a career as an armed robber who explains to his victims--in the story a used car salesman and the clerk at an IHOP- or Waffle House-style restaurant--like a sort of Ralph Nader wannabe how their businesses in particular and our entire civilization in general are fundamentally corrupt, which he feels renders his crimes unexceptional. He is captured down in Washington, D.C. when he tries to terrorize or perhaps rape or murder a senator.The dialogue in this story is amusing, and the story has some level of tension because the reader cannot be quite sure to what extent Malzberg wants us to nod along with the narrator's denunciations of capitalism and bourgeois government, pityingly seeing him as a nut driven insane by C&BG, and/or simply regard him as a rapacious robber who is rationalizing his villainy. We might see in this story one of the themes we see in "On Account of Darkness"--creative types have contempt for business people and government lackeys, but every day they must face the reality that business people and government goons are more powerful than they and must be appeased if they seek to prosper, or even survive. I also like the story because I grew up in Northern New Jersey and lived in New York City and so have some familiarity with the highways mentioned in the story, among them Route 46 and Route 80. My in-laws are from the Midwest and always say "I-80" but I stubbornly insist on saying "Route 80" and even did so when I lived in Iowa and Ohio, and so always like seeing "Route 80," or, as here, "Route Eighty," in print.

"Varieties of Religious Experience" debuted in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine under the title "Every Day in Every Way," something isfdb doesn't know but which I figured out myself by looking through issues of AHMM at luminist.org. We're doing original research here at MPFLog!

"Inside Out" (1978)

Here we have another story which debuted in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. In his afterword Malzberg tells us the premise of the story was suggested by AHMM editor Eleanor Sullivan; apparently Sullivan, unlike previous AHMM editor Ernest Hutter, liked Malzberg's work. Malzberg also praises Randall Garrett (specifically "Hunting Lodge") and Christopher Anvil ("Mind Partner.")The story is acceptable. While your humble blogger loved living in the Big City in the '90s and 2000s, the narrator hates living in town in the '70s. Everybody gets on his nerves, from the incompetent super of his building to the pathetic wretch who demands money for wiping his windshield to the woman at his office (he's a caseworker for the welfare department) who belittles him for his limited understanding of psychological theory and for spacing out during meetings. He relieves the tension he feels by having elaborate fantasies in which he murders these people. Uh oh...did he just flip his lid and actually kill one of these annoying characters in real life?

As in "Varieties of Religious Experience," readers are perhaps expected to sympathize with the criminal, see him as a victim of our society driven to acts of evil, and, in his afterword, Malzberg obliquely notes that these characters share personality traits and life experiences with himself.

"Inside Out" was reprinted in one of those Barnes and Noble "100 Whatever" anthologies, this one with Isaac Asimov's moniker on the cover!

**********

Am I going soft? Am I growing ever more in sync with Malzberg's sensibilities? Is this a statistical anomaly? Out of five stories, I'm finding three good and two acceptable. Whatever the diagnosis, today we've got what I consider a very palatable helping of Seventies Malzbergiana! And the good news is that there is enough left of The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady for two more servings, so stay tuned to see if we are going from strength to strength or today is a peak from which we are about to sadly descend!

.jpg)

_0001.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment