. Even though it is part of that series, it seems to stand perfectly well on its own.

A naked guy who has lost most of his memory finds himself in a corridor--a wall behind him is moving forward, compelling him to advance to a pair of doors labelled "AIR" and "WATER." He has only a brief period of time in which to select which door to open. The story describes the series of such choices he must make; it is implied that if he ever makes a wrong choice he will be killed by whatever fatal hazard lies behind the door which bears the "wrong" answer to the puzzle. One of the doors is labelled "TIGERS," presumably a reference to the famous story "The Lady or the Tiger?"

After surviving multiple such dilemmas, the protagonist comes to a choice between "PERPETUAL SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN HAPPY COMFORT" and "LIFE OR DEATH." Of course he chooses the latter--it is pretty common for SF stories to tell you that an easy life in a utopia is actually bad for people, that to be satisfied and to reach their potential people need challenge and risk. Anyway, behind the "LIFE OR DEATH" door the protagonist finds an office where sits a nurse with a robotic hand. The end of the story seems to suggest that the corridors were a test to see if he was suitable to colonize this alien planet and/or therapy to cure some psychological issue from which he was suffering, but now cannot remember--the nurse gives him a file folder full of information about himself, and in it he will learn what neurosis he has been liberated from.

"Black Corridor" is well written, and the plot is acceptable, so I can give this one a mild recommendation. It is followed (as all the stories in the

Masters of Darkness books are) by an Author's Note; Leiber in his describes the circumstances in which he wrote the story, places it in context within the speculative fiction field, and dedicates it to Robert Heinlein, whom Leiber praises as an inspiration and an educator. The themes of "Black Corridor" perhaps bear some resemblance to those of Heinlein's

Tunnel in the Sky, in which students face a potentially lethal final exam that consists of surviving on an alien planet and have to make such basic decisions as what equipment and weapons to bring and whether to work in teams or individually.

"Black Corridor" seems to have been reprinted in French and Italian more often than in English; it appears in two different Urania anthologies with Karel Thole covers.

"Strangers on Paradise" by Damon Knight (1986)

This is another of those stories I was just alluding to that suggest the easy life in a utopia is not all it is cracked up to be; I guess we get so many of these stories because scientific and technological advances since the Industrial Revolution have made material life so much easier, and at the same time a wide range of political actors have promised to improve the lives of their clients via vigorous government intervention into the economy--these anti-utopian and utopian-skeptical stories remind us that changes that appear good on the surface or in the short term or for particular interest groups might have painful unintended consequences, impose serious long term costs, or entail trespassing on the rights of people outside a political actor's constituency or inflicting harm on society as a whole.

"Strangers on Paradise" is set in the 22nd century. The human race has developed teleporter technology and is exploring the galaxy; for the teleporters to operate, both a transmitter and a receiver are required, so exploration is relatively slow, as it takes decades to fly to an unexplored star system and deploy there a teleporter receiver.

Thus far, the human race has discovered and colonized only one Earth-type planet, Paradise. There is no disease on Paradise, nor any crime or pollution, and the colonists keep it that way by strictly controlling who can visit and who can immigrate. Our hero, an Irish professor of English based at a Canadian university, is one of the lucky few allowed to land on Paradise after spending three months on a medical satellite having his body disinfected. (Knight presumably affiliated him with bland anodyne nations so we wouldn't think the prof represents the Cold War West or Western imperialism or whatever.) The prof has come to Paradise to conduct research on a female poet who was permitted to move to Paradise some 30-odd years ago; she died two or three years ago.

The prof finds Paradise as advertised--everybody is happy and friendly and good-looking, the air is clean and nobody ever gets sick. But buried in the poet's papers he finds a secret message--she figured out that the original colonists massacred the entire population of intelligent natives! Paradise is built on a foundation of genocide!

The prof keeps his knowledge to himself. It is suggested that the Paradisans might permit him to immigrate to their peaceful Edenic world, and it is implied that a university job and relationships with attractive women will be available to him, but he decides to return to Earth, which is polluted and full of germs. It appears that he is not going to reveal the horrible truth about Paradise--he cancels his plans to write a book about the poet.

All the science fiction business in "Strangers on Paradise"--the means of travel and the alien species and the medical developments--is good, and the pacing and plot structure are as well, and the twist ending is actually surprising but not outlandish. The story's themes have broad appeal; the story will resonate not only with anti-utopians like me, but also lefties who will see the story as an attack on religious people (the first colonists were members of a "Geneite sect" and one Paradisian flatly declares that the planet was given to humanity by God) and on the United States--one has to assume that we are supposed to see Paradise and its extinct natives as stand-ins for North America and American Indians. At the same time I will note that there are clues that we are expected to see Paradise as being like Australia. For one thing, the extinct natives are referred to as "aborigines." Secondly, the prof, in an act of sabotage, frees a male and a female rabbit from a lab--these

rabbits have been given an experimental treatment that is likely to have made them immortal, and Paradise lacks any predators large enough to take down even a rabbit.

I am a Knight skeptic and have attacked many of the man's works of fiction at this here blog, so it always feels good to find a story by Knight that is easy to like, because it makes the respect he receives more intelligible, and because it reassures me that my low opinion of so many of his stories is a fair and rational response to individual stories and not the product of prejudice or a subconscious campaign of vengeance for Knight's infamous hostility to A. E. van Vogt.

Thumbs up!

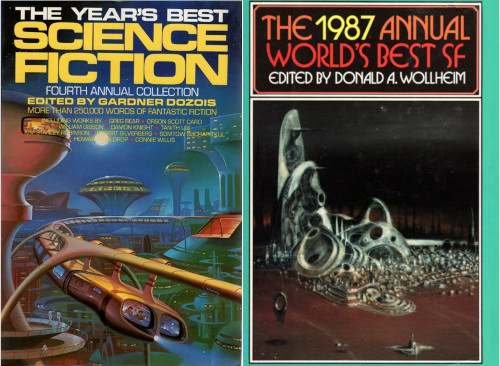

When it first appeared in F&SF, this story bore the title "Strangers in Paradise." Gardner Dozois and Donald Wollheim both included the story in their annual "Best of" volumes in 1987, suggesting that this story was a big hit in the SF community. In his Author's Note, however, Knight suggests he had trouble selling the story because it is such a misanthropic downer. He doesn't name the editors who rejected the story, though if we look at the big magazines in 1985 and '86, Analog was being edited by Stanley Schmidt, Amazing by George H. Scithers, Asimov's by Shawna McCarthy ('85) and Dozois ('86), and Omni by shifting combinations of Ellen Datlow, Gurney Williams III, and Patrice Adcroft.

"Gemini" by Tanith Lee (1981)

On a recent trip to Wonder Book in Hagerstown, MD, I spotted a copy of the ninth volume of Roy Torgeson's

Chrysalis series, which purports to contain the "Best All-New Science Fiction Stories." When I saw that it contained a Tanith Lee story I didn't recognize, I whipped out my smartphone to figure out if I could find that tale online someplace, an act which incepted this current

Masters of Darkness-centric project.

Gemmina, our narrator, is a beautiful blonde who is pathologically shy. She lives in some alternate universe or alien planet or far future or whatever where there is a socialistic government which provides a UBI and demands ten days of service four times a year. This society still has private property, though, and Gemmina lives alone on her family's ancestral estate in a mansion which, via robotics or magic, cleans itself.

One of the mysteries of Lee's story is how Gemmina seems to anthropomorphize her insecurities about other people, talking to us as if she had living within her a jealous vampiric entity that wants her all to itself. When women try to make friends with her or men try to seduce her this entity inflicts pain on her, makes her shun or fight those who would get close to her. When she looks into a mirror this entity feeds on her beauty. Is some creature living within Gemmina, or is she just nuts?

Another mystery has to do with Gemmina's identity, and her resemblance to some blonde deities of her people, an incestuous pair of androgynous twins, a slender girl with small breasts and a thin boy with no facial hair. These deities are named Gemmina and Gemmini. Outside her mansion, our narrator wears a brown wig so her blonde hair, "the hair of the golden Twins," won't attract attention.

As an intellectual and artist, for her quarterly ten-day service Gemmina is generally assigned to work in libraries or art galleries (this story has elements of a grad student's wish-fulfillment fantasies, what with the stigma-free dole and having to work only 40 days a year, and that at a solitary creative job.) In the period covered by the story she is cataloging books and painting a mural in the Library of Inanimate Beauty. The mural is of the golden Twins Gemmina and Gemmini holding hands.

The plot of the story, once all the background is out of the way, concerns an attractive young man she meets in that Library during her service. This ill-fated man endeavors to approach Gemmina, and, driven by the jealous entity within her that seeks to keep her all to itself, Gemmina pushes him off a balcony to his death. As the story ends, the government begins investigating our narrator in connection with the disappearance of that young man, and it is hinted that a disaster in Gemmina's life is looming.

Pretty good. Lee is a master of mood and image and all that, and "Gemini" delivers that stuff as well as the solid plot and setting I have described above. In her Author's Note, Lee comes right out and tells us that there is no alien entity possessing the narrator, that Gemmina has a psychological problem, what Lee calls "a case of bad nerves," and has constructed an artificial male oppressor to justify her unhealthy fears and distance herself from the moral implications of her anti-social behavior.

"Gemini" would resurface in the Lee collection put out by the Women's Press in 1989, Women as Demons.

"Glimmer, Glimmer" by George Alec Effinger (1987)

I think I have read nine stories by Effinger over the course of this blog's improbable life; here the long-suffering staff of MPorcius Fiction Log presents a list of them, complete with links to my blog posts about them and even representative quotes from those posts for the TLDR crowd:

"Ibid." ("a decent

Twilight Zone-style story")

It looks like I only liked three of those nine. Will today's Effinger story, my tenth, improve my view of the man's oeuvre? "Glimmer, Glimmer" debuted in an issue of Playboy the cover of which is dominated by the mug of Howard Stern Show habitue Jessica Hahn, about whom I have not thought in many years. Besides in Masters of Darkness II, "Glimmer, Glimmer" would be reprinted in the Effinger collection Live! From Planet Earth.

Rosa is a scientist, married to Joey, a man who inherited his father's dress shop and has built it into a business empire with outlets in hundreds of shopping malls. Their marriage isn't working out so well--Joey can't take any time off of work to spend with Rosa, but somehow he finds time to cheat on her with a woman named Melinda. As the story begins, this couple is taking their first vacation together in over a decade, biking cross country from one national forest or state park to another. Joey planned this vacation without much of any input from Rosa, and it often leaves them alone, far from any other people, leading us readers to suspect Joey has brought Rosa deep into the wilderness with the idea of murdering her!

Whether or not Joey was capable of murder we will never know, but one thing is for sure--Rosa is willing and able to commit murder in the first degree! Uninterested in settling for only half of the fortune Joey's hard work has accumulated, Rosa eschews the idea of divorcing her unfaithful husband and instead leverages her knowledge of biochemistry and insects to set a deadly trap for Joey.

This is a pretty good crime story that has a relationship drama at its core and employs a science gimmick, like we might expect of a science fiction writer. Probably more interesting to social science and humanities types than the way Rosa uses her hard science knowledge of insects and chemistry to kill somebody is the matter of the story's gender and class politics: is "Glimmer, Glimmer" a feminist/leftist story in which a capable professional woman--a woman who fucking loves science!--wreaks a just punishment on a grasping nouveau riche bourgeois striver? Or is it a misogynist/populist story about how women are cunning and manipulative and duplicitous and love money more than anything and will spread their legs or stab you in the back in order to get it from you, and how the credentialed elite of the non-profit sector have contempt for real work and will use their diabolical cleverness and esoteric knowledge to steal the fruits of your honest labor from you!

I like it.

**********

Four good stories in a row, from four different authors? How often does that happen? When an English professor of the future studies this blog, he, she or they will recognize this as a black swan event!

I ordered THE COMPLETE MASTERS OF DARKNESS after reading you excellent review. It arrived...and it is a Big Book!

ReplyDeleteAwesome! I hope you enjoy it! Some of the Author's Notes are pretty interesting. And thanks for your generous words about the blog and for reading!

Delete