But first! Links to my blog posts about the two stories in the 1954 printing of My Best Science Fiction Story that I have already read! Sometimes I wish I had an assistant or intern to do this kind of literary scut work, tracking down old files and copying and pasting links and all that, but then I remember how I felt about the college professors I did such work for--I certainly don't want to inspire anybody to feel that way about me.

I read A. E. van Vogt's "Project Spaceship" in 2016 in my copy of The Proxy Intelligence and Other Mind Benders, where it appears as "The Problem Professor." Here in My Favorite Science Fiction Story our man Van says he selected it because in it he tackles the problems of writing about the present, which are different from the challenges of writing about the future. ("Project Spaceship" is about how people are reluctant to fund the space program.)

I read Henry Kuttner's "Don't Look Now" in 2014 when I was reading a British paperback collection of Kuttner's work, and denounced it as a lame joke story that was not funny. Looking at Kuttner's intro to it in My Favorite Science Fiction Story, we see that Kuttner resorted to lame jokes here as well, not even pretending to sincerely explain why he thought it his best work.

(I like so many of Kuttner and Moore's horror and adventure stories, and much of their more serious SF work, like "Private Eye," Fury and "Two-Handed Engine," but I just don't grok their humor material.)

Alright, now on to the main event.

"Almost Human" by Robert Bloch (1943)

After the prof is eliminated (by his own creation!) Duke and Wilson decamp to a new hideout, from which Duke directs the robot in the commission of a series of profitable robberies and attendant murders. But the robot can read books, and learns about love, and falls in love with Wilson! Which of the two criminals, Duke or his mechanical protégé, will come out on top in this bizarre love triangle?

This is a better story than most of Bloch's output--Bloch actually does a good job with the character of Lola Wilson, who is wracked by guilt for aiding Duke in the commission of his crimes and is stricken by fear of the robot--her scenes with the robot are quite effective horror material. Bloch also refrains from his typical puns and jokes for this story, a demonstration of restraint I very much appreciate. Thumbs up!

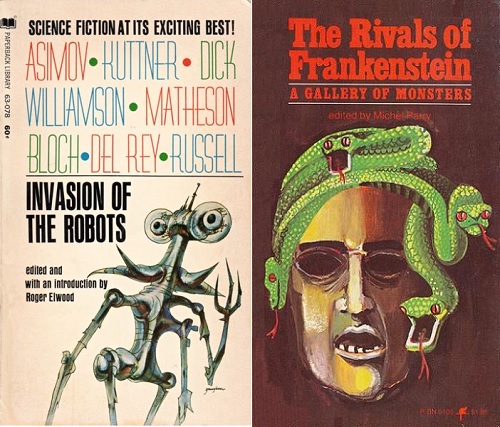

"Almost Human" made its debut in Fantastic Adventures, where it appeared under a pseudonym, Tarleton Fiske, and has since been included in such anthologies as Roger Elwood's Invasion of the Robots and Michel Parry's The Rivals of Frankenstein, as well as Bloch collections.

"Blindness" by John W. Campbell, Jr. (1935)"Blindness" first appeared in Astounding under Campbell's Don A. Stuart pen name, a few years before he himself would become editor of the magazine. It hasn't been anthologized much, but has been reprinted in many Campbell collections. In his intro here in My Best Science Fiction Story, Campbell tells us that the version we are about to read was revised slightly, and reiterates the main point of the story, that the biggest and flashiest discoveries and inventions are not always the most important, offering as an example the tiny and relatively simple, but revolutionary, transistor.

"Blindness" comes to us as a sort of brief biography or memoir of a scientist and it is full of hard science; it is a good example of SF that presents itself as a document written in the future and romanticizes the figure of the scientist, the seeker after knowledge who is willing to sacrifice himself for the benefit of the human race, but it does not portray the scientist as infallible.

Born in 1974, Malcolm Mackay devoted his life and money to developing nuclear power, which he saw as key to the economy of Earth and to space travel, a means of eliminating pollution, easing the burden of labor on the average man, and opening up vast new opportunities for everybody. During decade after decade of work he suffered many radiation burns and injuries from explosions, but the secret of atomic power eluded him. So, in his seventies, he decided there was only one course left to him--investigating the Sun at close range to learn the secret of the explosions that power old Sol!

Mackay invents the necessary materials, designs the necessary space ship, and then in 2050 this crusader and his right hand man John Burns fly closer to the Sun than anybody ever has to orbit that mighty star and perform all kinds of observations and calculations. They are totally isolated from Earth, as the Sun's radiation jams all reception of messages from Terra, and every day radiation that leaks through their shielding damages their bodies. They are in a race against time--not only is the radiation killing them, but they didn't bring enough fuel to escape solar orbit, instead gambling that they would learn enough about the atom to build the first nuclear reactor and use its power to fly back to Earth before their orbit decayed and they crashed into the Sun!

Mackay goes blind from all that radiation, but after three years he and Burns crack the secret of how atomic reactions work and build a reactor and an ion engine with which to propel themselves back home. And then comes our twist ending. The special material Mackay invented to make his space ship out of, something that could survive proximity to the Sun, has an amazing byproduct effect the implications of which he and Burns didn't think through, but which were recognized after they left. This material is the basis for a simple device that can generate practically free energy, and while our heroes were gone it revolutionized life on Earth--Mackay went to the Sun and sacrificed his health to develop cheap energy, but he had unknowingly developed it before he even left!

This story is paragraph after paragraph of science and engineering, but there is enough human stuff to make it palatable and the surprise ending is a decent payoff. Maybe the most interesting thing about the story for us 21st-century readers is the fact that, in real life, developing nuclear reactors was easier than portrayed in the story, and it is getting people to widely adopt them that has been the real challenge.

"The Inn Outside the World" by Edmond Hamilton (1945)

Hamilton wrote a multitude of adventure and horror stories full of battles and torture, but for his best story he chose this gimmicky philosophical tale. I am sympathetic to the point of the story, but "The Inn Outside the World" is kind of silly and boring.World War II has ended. Carlus Guinard, statesman, has returned to his native land, an unnamed Balkan nation, to try to put things in order, but this is a tough job, as the population is enflamed with "intolerance," "old grudges" and perfidious ambition. A U.S. Army officer, Lieutenant Merrill, is assigned to guard Guinard. One night Merrill hears something going on in Guinard's room, and barges in to find the Balkan statesman messing around with some strange doohickey that looks like a watch. The item in question is an interdimensional transport device, and Merrill ends up accidentally hitching a ride with Guinard to another universe!

It turns out that long ago a genius in Atlantis discovered how to travel to this alien dimension, which is adjacent to all history; here people from different periods of time can meet each other. The Atlantean gave the secret of the transporter device to only a few of the greatest men of the next generation, and they gave the secret to only a few of the greatest men of the generation that followed them, and so on, so that here in this dimension people like Socrates, Spinoza, Francis Bacon and Benjamin Franklin can meet and hang out. Of course there are rules that limit exploitation and abuse of this fabulous phenomenon, like you can't tell people from periods earlier than yours how they will die, and you can't provide direct aid to people from other periods of history.

Guinard, one of the great men selected by the generation before him for membership in this exclusive club, was so disturbed and desperate over the awful fix his country is in that he has come to request of the various geniuses that they make an exception to the rules and help him out. Maybe futuristic technology could hypnotize the people of the Balkans into behaving! A debate ensues on whether the rules should be broken to help Guinard. At one point Merrill draws his pistol to try to threaten the luminaries into helping Guinard; Julius Caesar approves of this aggressive tactic, but it fails and everybody else thinks this just proves that the 20th century is the century of jackasses. Anyway, a guy from the far far future, who is in fact the last human being, convinces everybody that since history is determined it doesn't matter what happens, who wins and who loses, but how we conduct ourselves, whether we act with courage and kindness, or otherwise. Guinard realizes it was a mistake to ask for help from other time periods, and a mistake to flag in his determination to do his best because the task ahead was so challenging.

I guess I agree with the story's sentiment, but Hamilton doesn't present his argument in an exciting or entertaining way, he just has some fictional jokers straightforwardly express it. There is no drama or suspense or surprise or anything. Barely acceptable.

"The Inn Outside the World" first appeared in Weird Tales, as the cover story no less, and would later be included in the Hamilton collection What's It Like Out There? and Other Stories and the textbook Science Fact/Fiction.

**********

I was fully expecting to enjoy the Hamilton more than the Bloch and Campbell, but Bloch and Campbell pleasantly surprised me and Hamilton disappointed me a little. It feels like, while Bloch and Campbell actually chose stories of theirs which legitimately had plotting and characterizations superior to that in much of their work, Hamilton, instead of choosing the most well-crafted or most fun of his stories, chose the one that most baldly conveyed an important piece of wisdom. I guess his heart was in the right place, but IMHO by 1945 Hamilton had probably written 50 or 60 stories better than "The Inn Outside the World."

Maybe we'll look into the stories in My Best Science Fiction Story by Muray Leinster, Manly Wade Wellman and Jack Williamson in the future, but in our next episode we'll be digging further into the early career of Robert Bloch.

I enjoy your reviews of these stories, but I'm also impressed by the various cover artwork on these old magazines and books. Contemporary SF artwork seems mostly sterile to me. Currently, I find the best artwork on the covers of small press books.

ReplyDeleteThanks! It is fun reading the stories and coming up with some way to describe my responses to them.

DeleteI have to agree about the cover art of much current SF. I'm exactly the kind of person who suspects our culture has become decadent and can no longer produce vibrant original work but instead churns out pale imitations and bitter parodies of older work, but to be more objective, it may just be that tastes change, and maybe mine hasn't changed with the times, and maybe financial incentives are such now that the most ambitious and original and industrious and talented artists are working in Hollywood or on video games instead of painting covers for genre literature.

The bright side of our era, of course, is that high technology and institutions like isfdb and internet archive have made all the fine old things easily accessible to people with limited time and financial resources like myself.

I agree with you on our current decadent culture. But I suspect the crappy cover art work on most paperbacks today have to do with cutting costs. Publishers don't want to pay for first-class cover artwork unless they are a small press who have a clientele willing to pay for quality.

ReplyDeleteThe Hamilton story happens to be one of my personal favorites.

ReplyDelete