The inside cover of the magazine is an ad for a Mickey Rooney film in which Rooney plays a race car driver. A Lina Romay is listed in the credits but maybe not the Lina Romay you are thinking of--the Spanish Lina Romay from all those Franco movies took her stage name in honor of the Mexican singer who worked with Xavier Cugat and Droopy.

The editorial space of this issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories is devoted to promoting Fantastic Story Quarterly, a new magazine that we are told will reprint SF classics from earlier decades (it was published from 1950 to 1955, changing its title along the way to Fantastic Story Magazine) and to a gushing book review by Robert Heinlein of The Conquest of Space, a book of Chesley Bonestell paintings with science text by Willy Ley. This book is available at the internet archive, and some of the color reproductions, like those of Saturn as seen from Titan, Mimas and Japetus, are pretty terrific.

"The Dancing Girl of Ganymede" by Leigh Brackett

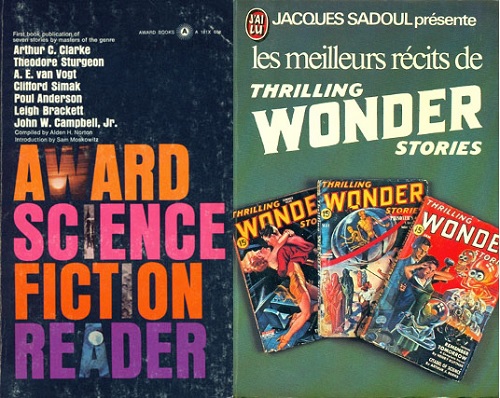

"The Dancing Girl of Ganymede" would go on to be included in several Brackett collections as well as 1966's Award Science Fiction Reader and a French anthology of stories from Thrilling Wonder. Here in Thrilling Wonder it gets a good illustration by Virgil Finlay.

On a plateau a thousand feet above the jungle, under a sky half-filled by Jupiter, sits the city of Kamar. Low on funds, close to the point of having to steal food, Earthman Tony Harrah approaches the Street of Gamblers in hopes of improving his financial status by gambling. There is music in the square ahead, and a crowd, and something, a smell perhaps, that sets the aboriginal forest dwellers of Ganymede, people little more advanced than apes, to flight--before scampering away, Harrah's aboriginal friend Tok warns him that in the square lie evil and death.

Ignoring his friend's warning, Harrah steps up to the crowd and finds they are watching four space gypsies, a mongrel people with the blood of every intelligent race in the solar system flowing through their veins. Three gypsy men play musical instruments, to which a gypsy woman, the most beautiful Harrah has ever seen, dances. Her body is warm and sensuous, but her black eyes are cold and full of hate.

Kamar is a dirty city of mazy streets and dark ways, and home to packs of feral dogs abandoned by spacemen. These dogs don't like the smell of the dancing girl and set upon her! In the chaos that ensues as the maddened dogs attack gypsy and non-gypsy alike, Harrah helps the girl, carrying her off to safety. Fascinated by this woman, who in the fighting as in the dancing proved herself incredibly fast and surprisingly strong, who calls herself Marith (it means "forbidden") and says she hates all men and all women, he asks her to come home with him, and she agrees. But on the way home three men, one Earther, one Venusian, one Martian, hold them up at gunpoint and take the girl away.

"We want the--the girl, not you." His slow, deep voice hesitated oddly over that word, "girl."The three gypsy musicians show up--they are Marith's brothers. Using their physical strength to dominate Harrah, and their psychic powers to summon Tok (the gypsies can control Tok's primitive people with their minds in ways they can't a human being) they shanghai our heroes into helping them rescue Marith and kill the three kidnappers.

After this killing, Brackett throws us a curveball--Marith and her "brothers" are not multi-racial gypsies, that is a disguise--they are androids, artificial people! Androids were built among the Inner planets, given super strength and good looks and other abilities so they could perform difficult and dangerous tasks and to provide entertainment, but normal humans' fear of being supplanted by the vastly superior androids has lead to them being rounded up for destruction, and a secret underground war people beyond the asteroid belt haven't heard about yet. There are fewer than forty androids left, and they have made their way to almost lawless Ganymede, but anti-android teams, like the one that Mirath's comrades just massacred, are on their trail.

Harrah has to choose between staying loyal to his own born-of-woman people, or joining the factory-built androids. Of course, seeing as the superstrong androids can kill him out of hand, and he has, against his better judgement, fallen in love with Marith, he hasn't got much choice.

The group climbs down the plateau, which is easy for the monkey-like Tok and the superstrong androids, but impossible for Hannah, so the male androids effortlessly carry him. Throughout the story the inferiority of all-natural and organic humankind is thrown in Harrah's face by these artificial superbeings. Harrah is taken to the secret jungle base where the last of the androids are building a factory so they can mass produce an invincible army with which to take over the solar system. Lacking lust, greed, hunger, and fear, the androids are sure they will be better rulers than emotional and corrupt mankind has been.

But wait! Tok has sneaked away and rallied the aboriginal villagers! The ape-like natives of the Ganymedean jungle fear the emotionless androids as much as humans do, and have set the jungle on fire! All the androids will be burned to destruction--and Harrah along with them! Mankind is saved! Marith tells Harrah that she has learned to love from him, and the two embrace each other as the fire approaches, enjoying a moment of happiness before she is permanently deactivated and he is burned to death.

This is an entertaining story. I didn't know where Brackett was going from one minute to the next with this story, which in some ways resembles C. L. Moore's famous "Shambleau;" would Harrah die, would the androids take over, would Harrah and Marith be able to make peace between humanity and humanity's creation? The ending feels legit, though, with primitive and passionate natural man saved from emotionless advanced artificial man by people even more primitive and irrational, with a sad note, as the love between Marith and Harrah suggests it didn't have to be this way, that maybe there really was a choice besides slavery and extermination. The ambiguous approach taken here by Brackett, in which there is some kind of nuance to how both the humans and nonhumans are portrayed, and both sides are seen to be acting in an understandable way, is far more interesting and entertaining than what Ray Bradbury does in this same issue of Thrilling Wonder, in "Payment in Full," with its monstrously violent humans and oh so perfect goody two shoes Martians. Thumbs up.

"The Voice of the Lobster" by Henry Kuttner

Terrence Lao-T'se Macduff is a con man who travels the galaxy making a living through selling snake oil and gambling, smoothing the way for such activities by administering drugs, hormones and hypnosis to weaken people's sales resistance and by bribing corrupt officials. As the story begins Macduff is on Aldebaran Tau, a planet inhabited by plant people, and he is in trouble--the city is in an uproar because one of his frauds has been exposed and the Mayor is implicated. The streets are full of vengeful mobs. In the course of making his getaway, Macduff cheats a lobster-like Algolian at dice--the Algolian owns a Lesser Vegan, a slave girl who, like all Lesser Vegans, is dim-witted but protected by a psychic vibration she emanates that disarms people, putting them at ease, and Macduff acquires her. When Macduff, Lesser Vegan in tow, gets on a space liner he finds that the irate Algolian, now aware he has been cheated, is already aboard.

The Algolian is himself a card sharp and conman, and Macduff learns the lobsterman is involved in some industrial espionage, having stolen from Aldebaran Tau a plant whose seeds are of great value in the making of perfume; he has been paid to smuggle the plant to the liner's next port of call, planet Xeria, whose citizens have long tried, without success, to break the Aldebaranean monopoly on this valuable resource. As a stowaway, Macduff will be left off on Xeria along with the lobsterman. Macduff is also forced to work to pay for his passage, and he uses the access this provides him to the ship's inner workings to sabotage the valuable plant, making it useless to the Xerians in hopes that, in their rage at the lobsterman, they will side with Macduff should the lobsterman try to get revenge on him. A byproduct of this scheme is an opportunity for Macduff to make a lot of money--with the money he buys himself and the Lesser Vegan tickets to Lesser Vega, so he need not get off at Xeria; on Lesser Vega he frees the girl.

Kuttner plays all this for laughs; Macduff, who is overweight, is always comically running away from mobs or from the lobsterman, and Kuttner includes plenty of jokes and gags, like the silly Scottish accent of the space liner's captain ("Vurra weel,") and a Macbeth reference tied to Macduff's name. These jokes aren't actually laugh-out-loud funny, but they are not irritating. At the same time that this is a comic story, it has an intricate plot, with its many aliens it gives you the feeling of life in a vast multicultural galactic civilization, and, in classic Golden Age SF fashion, the hero overcomes enemies and achieves his goals by using intelligence, trickery and his knowledge of science. You might think of "The Voice of the Lobster" as a P. G. Wodehouse story in a Star Wars setting, with Macduff playing both the Bertie (scared goofball) and Jeeves (imperturbable problem-solver) roles. It also reminded me a little of something Jack Vance might do. Thumbs up.

"The Voice of the Lobster" has reappeared in several Kuttner collections, as well as in the oft-reprinted 1950s anthology Adventures in Tomorrow and a 1978 issue of the Croat magazine Sirius.

**********

In our last blog post I pointed out Marion Zimmer Bradley's fun and interesting letter. (I've never actually read any of Bradley's fiction, and I am aware of the abominable crimes she committed and abetted, but I'd be lying if I said I didn't find this letter charming.) Quite a few of the letters in this issue, though none written by anyone as prominent as Bradley (though John Jakes comes close, I guess) are good reading. Robert R. Smith argues that science fiction will soon be the greatest field in literature and claims that "the detective story has fallen to pieces," citing the fact that John D. MacDonald has abandoned detective fiction for SF. (Of course, in the event, MacDonald left SF behind to become one of the most successful of detective novelists.) Grad student Donald Allgeier writes in to say he favors Brackett, Kuttner (though he doesn't like the Hogben stories), Bradbury, and van Vogt, even though van Vogt's work is full of what Allgeier calls "obscurities." (This Allgeier guy has good taste!) Allgeir does complain that the illustrations contain too much "cheesecake," however. Gwen Cunningham loves the Hogben stories (as do Elizabeth Curtis and Bob Johnson), and also likes Brackett, though she erroneously thinks Brackett is a man (the editor sets her straight.) Pearle Appleford writes from South Africa to report that an import ban has kept all pulp magazines out of the country, and asks if any Thrilling Wonder readers who throw their SF magazines away might mail them to her instead. Many of the letters include jocular poems, and the editor responds to them with poems of his own; many of the letter writers rank the stories from the October issue, and there is a real diversity of opinion. The letters column gives one the feeling that Thrilling Wonder is the center of a whole community of people with their own in-jokes, feuds and friendships. And to bring things full circle the editor closes out the letters column by recommending you go out to the cinema to see Mickey Rooney in The Big Wheel!

No comments:

Post a Comment