Let's finish up my copy of the 1958 collection of Gerald Kersh stories On an Odd Note by reading the last five of its 13 offerings.

"The Brighton Monster" (1948)

Looks like this one was first printed in The Saturday Evening Post under the title "The Monster" and has since been reprinted in various Kersh collections and some SF anthologies.Our narrator, during the war, stumbled upon an 18th-century pamphlet in a basket of paper to be recycled and stuck it in his pocket, forgetting about it until two years after the war was over, when he was inspired to rush to the closet to retrieve it from his old uniform.

Kersh doesn't try to imitate 18th-century prose; the narrator mostly paraphrases the pamphlet. It relates how a Brighton fisherman in financial and marital difficulties (he is alleged to have cheated on his wife and impregnated a girl) discovered in the sea an unusual man, a man covered in tattoos of various animals--snakes, lizards, birds, insects, etc. Unable to speak any European languages, and extremely strong, the people of Brighton are divided over whether he is a human being or some kind of monster. After all, how could a human man have survived underwater for as long as this creature apparently had? The presence of the strange man causes some strife, as the fisherman who found him doesn't get the price he thinks he deserves from the pamphlet-writer, a vicar and natural philosopher, to whom he sells this unfortunate individual, and then the fisherman's companion demands a cut of the payout, etc. The strange man escapes back into the sea after being held in captivity and studied for some months by the vicar.

In 1947 the narrator is talking to a friend, an Army Intelligence officer who has been all over the world and knows all about unarmed combat--jujitsu, wrestling, etc. He tells the story of a Japanese wrestler of his acquaintance who was apparently killed during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the description of whom sends the narrator racing to get the half-forgotten pamphlet. It turns out that that wrestler was transported through time and space by the atomic blast, to Georgian England, where the natives drove him to suicide!

Acceptable...maybe mildly good. Kersh includes lots of asides describing life in England during the Second World War, the appearance, personality and opinions of that Intelligence officer, and so on, but this ancillary stuff is entertaining, so I won't bitch about it the way I groused about Frank Belknap Long's digressions in Journey into Darkness. One of the interesting things about the story is how the narrator and the Intelligence officer deplore the atomic bomb and science in general; the story ends by highlighting the idea that the Japanese wrestler was the victim of scientists both in the 20th century and the Eighteenth.

"The Extraordinarily Horrible Dummy" (1939)

Resist the temptation to make the obvious joke about that politician you don't like or your ex!"The Extraordinarily Horrible Dummy" first appeared in Penguin Parade 6, and would reappear in several magazines, anthologies, and Kersh collections. It is a brief and effective tale. The narrator is living in a crappy London hotel for impecunious losers. He meets his next door neighbor, Ecco the ventriloquist, a nervous and high strung guy who has a particularly ugly dummy. The narrator thinks this guy is a genius ventriloquist, but Ecco explains that he is actually a mediocre ventriloquist--his father was the genius ventriloquist. Dad ruthlessly browbeat his son, trying to teach him the family trade, but was never satisfied with Ecco's performance. When Ecco was 20, Dad died (it is hinted Ecco murdered him) and Dad's ghost took up residence in the dummy and has continued to berate his son mercilessly ever since.

It is sort of basic, but I like it.

"Fantasy of a Hunted Man" (1942)

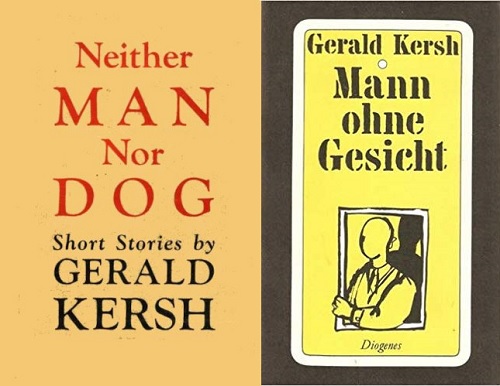

An issue of John Bull with an ad for cocoa on its cover appears to be the venue in which "Fantasy of a Hunted Man" first appeared under the pseudonym "Waldo Kellar." Not the hit "The Extraordinarily Horrible Dummy" was, the tale has only been reprinted here in On an Odd Note, in Neither Man Nor Dog, and in a Swiss collection.In "Fantasy of a Hunted Man" Englishman Kersh writes about racism in the American South. "Fantasy of a Hunted Man" is also one of those switcheroo stories, like that Twilight Zone in which a U-boat captain magically finds himself aboard a defenseless ship about to be torpedoed, or all those stories in which a guy who hunts is then hunted, or a guy who kills bugs is then killed by a giant bug, or whatever.

The Major is a tough old character, brave, resourceful, determined to do his duty. He is also a racist who hates blacks and foreigners. One day a black guy, Prosper, innocently approaches a white woman who lives nearby, and the hysterical female flees, screaming bloody murder. A lynch mob forms, and the Major is its leader! Prosper runs for his life, leaving the mob far behind--except for the Major, who refuses to give up! Finally, exhausted, the sixty-year old Major stops to rest and falls asleep. While he is asleep his soul and that of Prosper are switched! The Major, for a few hours, knows the fear felt by Prosper! Prosper, in the Major's body, begs the mob for mercy; the mob thinks the Major has gone insane and this distracts them and they abandon the search for Prosper. When their souls are switched back, the Major has become a kindly guy who no longer hates black people.

Acceptable--the story is short and sharp and direct, not too long, not overwritten. I generally find these switcheroo (Joanna Russ calls them "role reversal") stories tiresome, but "Fantasy of a Hunted Man" is better than many switcheroo stories; often such stories feel like self-indulgent revenge fantasies, and/or have boring flat one-dimensional characters. Fortunately, the Major is a sort of interesting character with admirable as well as deplorable personality traits, and the story, as it depicts a man growing and changing, has a beginning, middle and end and is not just a horror anecdote about some bastard the reader has been primed to hate getting punished ha ha ha.

"The Gentleman All in Black" (1942)

Another kind of story I generally find lame is the make-a-deal-with-the-Devil story. And here is Kersh's make-a-deal-with-the-Devil story, "The Gentleman All in Black," which I am giving a thumbs down--it is lame filler.The narrator knows a beggar in Paris, a beggar who has an apartment and who is reputed to have a secret stash of money. The beggar tells the narrator the story of his last day working as the sole clerk to Mahler, the great financier.

Mahler made a bad investment, and was so deep in debt he would have to go out of business. But then a man in fine black clothes and fine black jewelry arrived unexpectedly at the office. Mahler doesn't realize it, but of course this is the Devil. Mahler doesn't believe in the soul, so Satan doesn't offer to buy his soul; instead he offers to buy Mahler's time. "I will give you twenty million francs for one year of your life--one year in which you must devote yourself utterly to me." Mahler is a hard bargainer, and gets what looks like a good deal--fifty million francs for just one second of his time. The Devil puts the money on the table and moments later uses that one second of mastery over Mahler to order the financer to jump out the window to his death. The beggar, it is implied, seizes the money after Lucifer leaves but is reluctant to spend it.

Another Waldo Kellar story from John Bull that would reappear in Neither Man Nor Dog and that Swiss collection.

"The Eye" (1957)

"The Eye"'s debut appearance was in the Saturday Evening Post under the title "The Murderer's Eye." It would go on to be included in The Ugly Face of Love and in a 1965 anthology titled Great Detective Stories About Doctors.Harlan Ellison's gushing had lead me to expect Gerald Kersh's stories to be special, to be hard to understand and/or to have some kind of distinct, unique style--I guess I was expecting something comparable to Robert Aickman, R. A. Lafferty, Gene Wolfe, Jack Vance or Tanith Lee. But the stories in On an Odd Note are just ordinary; Kersh is a capable writer, but these stories aren't at all far out of the mainstream in content or style. Maybe it is his novels, which I understand are largely about the lives of desperate people in London and largely based on Kersh's own experiences, that led Ellison to sit up and take notice of Kersh. (Or maybe Ellison liked Kersh because Kersh was another rambunctious Jewish guy who was always getting into fights and other scrapes.) Well, when we read one of Kersh's World War II novels we'll see what we think.

I'm not surprised to learn that Kersh's stuff is 'meh', despite the hyping by Harlan. It's pretty much the same story with Harlan and 'Cordwainer Smith' aka Paul Linebarger. I remember sitting down with 'Norstrilia' back in 1975 and finding it not a 'cult classic', but an exercise in boredom. So I'm not in a rush to access Kersh's short stories. If they come my way I'll try 'em, but that's about it.

ReplyDeleteCordwainer Smith, I think, does have a distinctive voice, and so I'm not surprised he's not to your taste and I wouldn't be surprised if somebody said Cordwainer Smth was his favorite author.

DeleteI just got a Kersh WW2 novel from Abebooks, and his most successful (it has been made into a movie twice) novel Night and the City, so I'll have a better educated opinion of Kersh soon enough.