"The Green Meadow" by H. P. Lovecraft and Winifred Virginia Jackson (1927)

According to wikipedia, "The Green Meadow" was written by Lovecraft in 1918-1919, based on a dream of Jackson's. (The Weird Tales crowd loves recording and relating their dreams--remember when Frank Belknap Long included a dream of Lovecraft's in his The Horror From the Hills?) "The Green Meadow" was not published until 1927, in The Vagrant, an amateur press publication, where it appeared under the pen names "Elizabeth Neville Berkeley" and "Lewis Theobald, Jun." It would first see wide publication in the 1943 Arkham House collection, Beyond the Wall of Sleep.

"The Green Meadow" is like five pages long. A prefatory note tells us the main text is from a book made from an unidentifiable substance that was found inside a meteorite; this text is in ancient Greek, apparently the work of a scholar from classical Hellas.

The narrator of the brief document tells us he woke up or found himself on an alien world with little memory of his identity or past. He was on a narrow strip of land between bodies of water, and could see to one side the ocean and the other a forest. A bit of land upon which he was standing broke off and he rode it down a river, towards what sounded like a waterfall. He passed a strange meadow where creatures that looked like bushes (or were hiding within bushes) sang in an alien language. Suddenly, he remembered his identity, realizing (as characters in Lovecraft stories sometimes do) he is not really human; he won't write down the details, as such knowledge would drive us readers insane. (Thanks, pal.) The text abruptly ends, the book having been damaged in some way that obscured the narrator's handwriting.

A trifle, though it is interesting to see themes like the discovery of one's inhuman identity and the fact that true knowledge of the universe will drive you insane here in some of Lovecraft's earliest work.

"The Crawling Chaos" by H. P. Lovecraft and Winifred Virginia Jackson (1921)

Wikipedia tells us that "The Crawling Chaos," which was first published in what I guess is another of those amateur press periodicals, this one bearing the moniker The United Co-operative, was, like "The Green Meadow," written by HPL based on one of Jackson's dreams. It appeared under very similar pseudonyms there, and was not published again until 1970 in the first edition of The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions.

During a plague, the narrator was given opium to treat his plague symptoms, but his overworked doctor administered an overdose, resulting in the narrator having a crazy dream, apparently a vision of the far future. The dreamer finds himself in an exotic room in an exotic house, the house and its furnishings a mixture of Oriental and Occidental styles. The house sits upon a cliff on a narrow peninsula, and below an angry sea batters the cliff, ripping away chunks of earth, threatening to cause the peninsula to collapse. (I guess this sort of thing is a recurring theme in Jackson's dreams.) The narrator walks away from the house, and is met by beautiful people who have the power of gods; these people help him fly out into space--he looks back and watches as the Earth is destroyed. Then the narrator awakens from his opium dream, back in our plague-ridden but relatively mundane 20th-century world.

Another trifle, even less interesting than "The Green Meadow."

"The Last Test" by Adolphe de Castro and H. P. Lovecraft (1928)

I recently purchased a copy of Volume 9 of Hippocampus Press's Letters of H. P. Lovecraft, which is titled Letters to F. Lee Baldwin, Duane W. Rimel, and Nils Frome and was edited by David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi. Lovecraft discusses Adolphe de Castro at some length in several letters to F. Lee Baldwin, and de Castro, whom wikipedia describes as "a Jewish scholar, journalist, lawyer and author of poems, novels and short stories" comes across as a likable but wacky sort of character. For example, de Castro in 1934 asked Lovecraft to revise a book of essays in which he endorsed Bolshevism and put forward a theory that Jesus Christ was Pontius Pilate's illegitimate son (see letter of December 23, 1934, in which Lovecraft offers Baldwin a long list of reasons to believe de Castro's theory about Jesus's parentage is just a fiction de Castro made up and doesn't even believe himself.) Lovecraft appears to have passed on this assignment because de Castro couldn't pay in advance, and it seems the book of essays was never published.

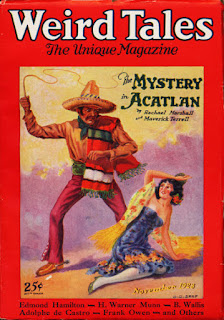

Anyway, one job Lovecraft did do for de Castro was revising "A Sacrifice to Science," a short story that de Castro had published in 1893 in his book In the Confessional and the Following. The revision appeared in Weird Tales in 1928, under the title "The Last Test." (By the way, this is the same issue of Weird Tales that includes Edmond Hamilton's "The Polar Doom," which we read in the summer of 2017.)

Dr. Alfred Clarendon has a reputation as a genius medical scientist with a single-minded obsession for discovering the truth. He was a world-renowned figure among the egghead set by age thirty, having traveled the globe conducting groundbreaking research on all manner of terrible diseases:

....he had taken long, lone jaunts to strange and distant places in his studies of exotic fevers and half-fabulous plagues; for he knew that it is out of the unknown lands of cryptic and immemorial Asia that most of the Earth's diseases spring.Whoa, ripped from today's headlines!

Clarendon returned to New York with a new personal assistant named Surama, a highly educated and skeletally thin North African, and a large staff of skeletally thin "Thibetans." Then he moved the entire household, including his sister Georgina, to a mansion in San Francisco.

In his youth in New York, Clarendon's best friend was this dude James Dalton, another of these go-getter types. While Clarendon was becoming a world authority on diseases and offering employment opportunities to the freakiest of the foreign freaks he would come across, Dalton was in sunny California, making his own fortune, and by the 1890s Dalton was governor of the Golden State. Just a few months after the two old cronies meet up in Cali and Dalton renews his youthful romance with Georgina, Dalton appoints Clarendon to the position of medical director of San Quentin. (Talk about cronyism!)

That background is covered in the first part of this 45-page story, which is broken into five parts. In Part II we see Clarendon in action as head of the prison medical staff as an epidemic of "black fever," about which Clarendon is the world expert, breaks out in the prison. A panic in San Francisco ensues, and a public controversy ensues, thanks largely to fake news promulgated by venal reporters (this story takes a very dim view of journalists): is Clarendon doing his level best to control the outbreak, or letting the disease spread unchecked among the prisoners in order to study it? At the same time Georgina and Dalton worry that the creepy Surama, who is always chuckling behind their backs, is having a malign influence on Clarendon.

In Part III disaster strikes Clarendon, as the California legislature, believing the worst about the doctor, passes a law that takes the power to appoint the head sawbones at San Quentin away from the Governor and gives it to the state prison board. Clarendon, who has no ability to schmooze with politicos or journalos and doesn't even read the newspapers, is sacked by the prison board. In Part IV the now-unemployed Clarendon experiments on animals in his private lab, the strange Surama at his side. Georgina, by chance, comes upon clues that hint at the horrible nature of her brother's relationship with the North African genius and their work; for example, when he is frustrated because his rigorous schedule of experiments has depleted his supply of test animals, Clarendon utters a fanatic diatribe about how the individual is nothing and must be sacrificed to the quest for knowledge for the good of the race--in this little speech he even mentions Atlantis and Yog-Sothoth. Even more chilling is Georgina's witnessing of Surama outfighting and then carrying off one of the Thibetans, apparently to be experimented on in place of the exhausted supply of test animals--even more bizarre is when she overhears a conversation between Surama and Clarendon in which the former implies he is thousands of years old!

In the fifth and final part of the tale Clarendon takes steps to use his own sister as a test subject, but the providential arrival of his best buddy Governor Dalton snaps him back to sanity. Clarendon explains to Dalton how he got mixed up with Surama, and what their research is really about--Surama is the last living member of a pre-human race that worships alien gods, and the black fever is no earthly disease, but a disease from another planet or dimension or something. Surama is a sadist and he somehow turned Clarendon into a sadist--Clarendon has been infecting animals and people with black fever not as part of a program of research but merely to enjoy watching their suffering! Now back in his right mind, Clarendon injects himself with the black fever and then burns down his lab while all his samples of the fever from beyond, as well as he and Surama, are in it, leaving the world to mourn the death of the great doctor and men of science to puzzle over Surama's queer half-mammalian and half-reptilian skeleton.

"The Last Test" is OK, no big deal. I was very disappointed when the themes of selfish ambition (a guy experiments on people against their will to further his career as a scientist) and of individual-crushing collectivism (a guy experiments on people against their will in order to pursue the greater good of abstract knowledge and triumph over disease) were tossed in the garbage in favor of the theme of sadistic perversion (a guy injects people with disease in order to enjoy watching them die.) This is a total waste of the character of Surama, an inhuman genius from Earth's prehistoric past with access to alien material--just any old 19th-century American creep can be a sadist, there is no reason to introduce antediluvian and otherworldly elements like Surama and Atlantis and Yog-Sothoth to the story if the main character is not going to be experimenting on people in order to achieve immortality or travel to another planet or conquer the world or something cool like that. The sadist elements and the Yog-Sothery elements just don't gel very well here. The sadism angle also robs the story of any philosophical or ideological interest; we all agree that torturing people for fun is wrong, but we all disagree over what the individual owes the community and what the community owes the individual, and we all make different calculations when it comes to compromising our principles in order to further our careers. Clarendon's science-obsessed youth and his "the individual must be willing to sacrifice himself for the collective" speech don't gel with the sadism element either--the sadism business renders all the interesting parts of Clarendon's character moot.

"The Last Test" was first printed in book form--and with Lovecraft's name on it--in 1949's Lovecraft collection Something About Cats and Other Pieces, and would go on to be included in many Lovecraft collections. De Castro's original version ("A Sacrifice to Science") appears along with "The Last Test" in a 2012 volume edited by the indefatigable Joshi entitled The Crawling Chaos and Others; maybe someday I'll get my hands on that book and compare both versions and puzzle out who is to blame for the story's problems. (Incidentally, I totally love Zach McCain's covers for The Crawling Chaos and Others and its companion volume, Medusa's Coil and Others.)

"The Electric Executioner" by Adolphe de Castro and H. P. Lovecraft (1930)

De Castro's first version of this story appeared under the title "The Automatic Executioner" in 1891 in the magazine The Wave, and then was reprinted in de Castro's collection In the Confessional and the Following. Lovecraft's revision of the story, re-titled "The Electric Executioner," appeared in Weird Tales in 1930 in an issue that also printed Robert E. Howard and Edmond Hamilton stories I haven't blogged about yet.

"The Electric Executioner" is like 18 pages long.

When the guy managing a Mexican silver mine for a San Francisco-based company disappears, absconding with all the important papers related to the mine's operation, the peeps in SF send our narrator, an auditor and investigator, down Mexico way to retrieve all those essential documents. Our narrator finds himself alone in a train car late at night with another American, a big strong man who quickly overpowers him. This menacing figure explains to our hero that he is a worshiper of ancient Mexican gods like Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopotchli (Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth are also in the mix) and also that he has invented a superior electric battery and uses it to power a portable electric execution device--he has the device here with him in his "portmanteau." This device (essentially a flexible wire hood attached to the battery by a cord) has not yet been tested, and the muscular inventor, of course, proposes testing it on our narrator.

The narrator doubts that any battery a man could carry could store enough juice to kill a person (this is the 1890s, remember)--he is sure the hulking inventor is simply insane. Of course, this nut is so huge--and armed with a gun and a knife, besides--that, physically, he is still an insurmountable opponent, and our hero assumes he will just murder him after the electric device inevitably fails to kill him, So, he uses his wits to get out of this terrifying jam. This part of the story is, I guess, supposed to be funny; thanks to the narrator's Bugs Bunny-like fast talking, and some sheer luck, the maniac ends up putting the hood over his own head and electrocuting himself with the device, which unexpectedly works as advertized.

The narrator faints when comes the blue flash and the inventor's screams, and when he wakes up the inventor and his device are gone! The last few pages of the story indicate that the mad inventor was in fact the fugitive mine manager our hero was sent to find; in league with native Mexican Indian Cthulhu-worshipers, the fugitive astrally projected himself onto the train from a cave temple, where his corpse and his device were discovered by those who investigated the screams and the smoke coming from the body's charred head.

This story is OK, I suppose. I'm not a big fan of joke stories, so I'm not really the audience for this one. The story doesn't marry its going-native-and-worshiping-Cthulhu-with-Indians and inventor-makes-a-super-battery-and-wants-to-use-it-to-kill-people components particularly well.

Historians of racism will perhaps find interesting that, while he considers the Indians of Mexico beside whom he worships alien gods to be "sacred and inviolate" "children of the feathered serpent," the insane inventor has contempt for Mexicans with Spanish blood and calls them "greasers."

Like "The Last Test," "The Electric Executioner" was first reprinted in Something About Cats and Other Pieces. De Castro's original story, "The Automatic Executioner," can be found in 2012's The Crawling Chaos and Others.

**********

These stories are all pretty disappointing, though at least none is as bad as "The Lurking Fear." I guess I can give all of them the all-too-common rating of "acceptable." Lovecraft's collaborations with Bishop and Heald were much more successful, maybe in part because Lovecraft was by that time a more experienced writer, maybe in part because Lovecraft had a much freer hand in developing them.

More Lovecraft collaborations in the next episode of MPoricus Fiction Log.

Hello! I couldn't find an email for contact, but I wanted to ask - do you know of any pulp/weird lit/sci fi stories where a variety of weird creatures/aliens/monsters are described in a single story? I appreciate any help you can provide!

ReplyDelete