|

| A German edition of The Best of Edmond Hamilton |

"Fessenden's Worlds" (1937)

This is a mad scientist story endorsed by H. P. Lovecraft-loving writer and publisher August Derleth, who included it in his 1950 anthology Beyond Time and Space. This anthology is huge (650 pages and 32 stories!) and offers an esoteric, wide-ranging selection of stories--I can't deny that it has my itchy ebay-finger twitching! Somewhat bizarrely, the paperback edition of Beyond Time and Space, published in 1958, includes only eight of the hardcover edition's stories, all by famous and important 20th-century SF writers (you'll be happy to know Hamilton made the cut!)

The first sentence of Hamilton's 1931 mad scientist story "The Man Who Evolved" is "There were three of us in Pollard's house on the night that I try vainly to forget" and the first sentence of "Fessenden's Worlds" is "I wish now that I'd never seen Fessenden's damnable experiment!" What is it with these snowflake narrators who don't fucking love science? Both stories also end with an accidental fire that destroys the mad scientist, his house, and all the evidence! No wonder scientific progress is at a virtual standstill!

Arnold Fessenden has been absent from the university for a while, skipping faculty meetings and enlisting assistants to teach his lecture courses, so our narrator, also a college prof, goes to visit him, curious to see what is up. Fessenden, he learns, has invented a bunch of machines--a gravity neutralizer and an atom shrinker that operates by contracting the orbits of electrons among them. Using these machines Fessenden has created a new universe, a tiny one three or four yards across shaped like a lends that looks like a dense mass of millions of immobile sparks. Each spark is a sun! (As he did in Outside the Universe, I get the feeling that Hamilton is using the word "universe" as we would use "galaxy.") Fessenden has super powerful microscopes that can focus in on individual planets in this universe, and because time in a tiny universe runs very very fast he can watch, over a period of a few minutes, primitive animals evolve into people and empires and civilizations rise and fall. He and the narrator do just this.

Fessenden is, declares the narrator, "the greatest scientist this planet ever produced--and the evilest!" Why "the evilest?" Well, Fessenden is not content to just observe the thousands of inhabited worlds that he has created in his laboratory--he likes to experiment on them! These experiments consist of testing a civilization's vigor and ingenuity by seeing if it is up to the challenge of surviving a collision with a comet, or a radical change in its sun's temperature, or contact with another civilization, stuff like that. These experiments, of course, kill billions of tiny people, something that appalls the narrator, much to the incredulity of Fessenden, who says that these people are his property and they are smaller than bacteria, so who cares!

This story may be more of a concept than a fully-fleshed out, fully-plotted story, but the idea is awesome and Hamilton vividly describes the numerous cool planets and exciting catastrophes the narrator observes, so I enjoyed it. "Fessenden's Worlds" first appeared in Weird Tales, and was illustrated by Virgil Finlay--check it out at the link. (Extra credit for all you SF scholars--compare "Fessenden's Worlds" to Ted Sturgeon's 1941 "Microcosmic God.")

"Easy Money" (1938)

It's another first-person narrative about a mad scientist, but this time our narrator is no college professor, but a simple-minded lunk, and our story is a light-hearted one. "Easy Money" has not been widely anthologized, appearing in Thrilling Wonder Stories and then not reappearing until The Best of Edmond Hamilton almost 40 years later.

Slugger Martin is an unemployed boxer, sitting in beautiful Battery Park wondering where his next meal is coming from, when he is accosted by scientist Francis Murtha. Murtha has invented a teleporter/matter transmitter kind of thing, and wants to test it out on somebody! He has used it to send rabbits to and retrieve them from alien worlds, but of course theses beasts can't describe their destinations to Murtha, so he wants to send a human. And he wants to send a human who isn't smart enough to steal his scientific secrets! Martin fits the bill, and when offered $1,000, accepts the job!

Martin is an uneducated dope, and Hamilton mines this for comedy, pulling all sorts of gags based on the fact that Martin doesn't know what is going on, but provides us readers information enough to clue us in to what is happening. Martin is transported to an alien planet, whose urbanized civilization of pyramidal skyscrapers is a peaceful and orderly one because its wisest member wears a "Controller helmet" which transmits his thoughts to everyone in the world, giving them homogeneous opinions, a strongly conformist attitude and a unity of purpose. I guess you could call "Easy Money" a "gadget story," because Hamilton offers speculations on what kind of society this device would produce, and because poor Martin, trial and error style, has to figure out how to use the device to get back to Earth.

Murtha's machine is proven a success when Martin reappears in his lab after his harrowing adventure. But like in the other Hamilton mad scientist stories, the invention does not survive--Murtha's experience "in Egypt" (he refuses to believe he has been sent to another planet) was so bad that he wrecks the matter transmitter to spare any other unfortunate fool from being subjected to it. These mad scientists can't catch a break!

A fun story, even if I have qualms about smart and educated people like Hamilton making sport of their intellectual inferiors. The premise (down-and-out boxer teleported to alien planet by scientist) is strangely reminiscent of Robert Howard's Almuric, which would appear in Weird Tales in 1939, three years after Howard's untimely death.

"He That Hath Wings" (1938)

Young widow Mrs. Rand just died in childbirth, and her baby is a hunchback! Sad! But wait! The Rands suffered injuries in an electrical explosion a year ago, the complications of which killed Mr. Rand a few months ago, and the hard radiation released by the explosion messed with their genes--their orphan baby David isn't a hunchback, he's the first human being with wings!

|

| My copy of The Best of Edmond Hamilton; there's David Rand in his carefree teenage years! |

At first David is happy to live with Ruth and work at her father's firm (imagine a world in which you don't need a college degree to get a cushy office job--hell, David didn't even go to grade school!) When Ruth gives birth to their child (no wings--the wing gene is apparently recessive) Mr. Hall even makes David the head of the company! (Holy nepotism, Birdman!) But David has started missing flying, and he hasn't told anybody that his wings are growing back! This second pair of wings may be short and stubby but they are better than nothing!

At night David tries out his stumpy wings, and it feels so good to fly again that he immediately decides to abandon Ruth, the brat, and his father-in-law's firm for the wild life of a bird. Unfortunately these stubby wings can't carry him far, but he sinks beneath the waves content to have died doing what he really loved!

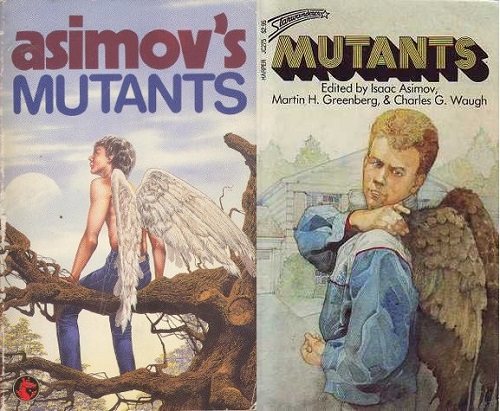

Here we have a story about the sacrifices we make, the ways we betray our true natures, to fit into society and to have sex. Are our sacrifices worth it? I thought it interesting that Hamilton seemed to be suggesting that they are not! "He That Hath Wings" is kind of sappy and sentimental, and feels a little long, but it gets a passing grade. It is an acceptable example of a SF story that is about human life and relationships, but throws a lot of science at you like the Asimov types think science fiction is supposed to. After first appearing in Weird Tales, "He That Hath Wings" was reprinted in Fantastic in 1963 accompanied by a bibliographic essay by SF fan extraordinaire and historian Sam Moskowitz and an illustration by Virgil Finlay, and later in a few collections of stories from Weird Tales and anthologies of stories about mutants.

Brackett and Moskowitz think the sentimental "He That Hath Wings" is one of Hamilton's very best stories, but I have to admit I found greater enjoyment in the cynical, violent, and at times humorous mad scientist stories "Easy Money" and "Fessenden's Worlds."

In our next installment of our Hamilton-Brackett series, two Leigh Brackett cover stories from the early '50s!

"Fessenden's Worlds" wasn't Hamilton's only story about a mad scientist with a toy universe in his basement lab; he also wrote "The Cosmic Pantograph" on that theme. Then there's Jack Williamson's "The Pygmy Planet" but that was just one planet. And R. A. Lafferty's "The Wooly World of Barnaby Sheen".

ReplyDeleteThanks for the useful comment! These all sound like stories I would be interested in checking out!

Delete