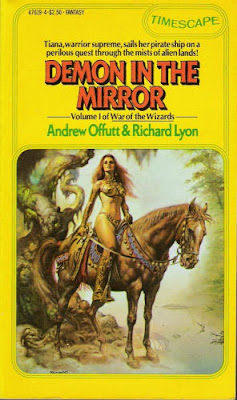

His laugh was part irony, part true amusement. That Tiana woman was a magnificent fool. He had explained to her the hopelessness of the odds against them...and she remained arrogantly confident. The fire-haired beauty was certain that her wit, strength and skill would bring her out victorious! If vanity and confidence were gold, he mused, it's she who'd be the owner of the world!It is time to finish Andrew Offutt and Richard Lyon's War of the Wizards trilogy--here is the third volume, 1981's Web of the Spider. Web of the Spider was part of Pocket's Timescape line; "Timescape," we see on the publication page, is a trademark owned by Gregory Benford. (That's a little SF trivia for you.)

Like Part Two of War of the Wizards, The Eyes of Sarsis, Part Three has a cover by Rowena Morrill. I think this is one of Morrill's better paintings--the flying woman's pose seems more balanced and less static, and her face has more life than the people in many of Morrill's other covers. I am apparently not alone in thinking this an above average sample of Morrill's work--this painting was the cover for 1983's collection of Morrill's work, The Fantastic Art of Rowena.

This third volume of Offutt and Lyon's trilogy is an elaborate production, with 24 pages of glossary and gazetteer in the back, and a two-page map of Tiana's world in the front. (A look at the map and gazetteer reveals that some of the geographical names are homages to Edgar Rice Burroughs.) Preceding the main text, there's even a (terrible) poem about Tiana, Pyre and Ekron! War of the Wizards is a labor of love, and Offutt and Lyon put real effort into it, which you can see in the text, and which is a welcome contrast to things like Ken Bulmer's Kandar, which feel like they were just thrown together haphazardly to meet a deadline.

Back in 2015, when I read Andrew Offutt's The Iron Lords, I reported that Offutt used repetition to give that novel a poetic and epic feel, and in the brief "Prolog" to Web of the Spider, in which we gain insight into the character of antagonist Ekron, the wizard, we see him employing these devices again. For example, in just three short pages Ekron is described numerous as he whose "soul was that of a toad and whose god was the Spider."

The beginning of the main text feels like a mash up of elements from the earlier Tiana books. We find our heroine a captive of King Hartes of Thesia, and it isn't long before the Thesian High Magistrate is pressuring Tiana to go on some dangerous mission--the same sort of thing happened to Tiana, and to other pirate captains, in The Eyes of Sarsis. The High Magistrate knows a way Tiana can fake her death and escape being burned alive in the execution scheduled for her--quite reminiscent of the aristocrat in The Demon in the Mirror who knew a way Tiana could play possum and be buried alive in order to sneak into the royal tomb she wanted to loot.

(In case you are wondering, that is Tiana on the cover in the costume she was given to wear for her theatrical execution ceremony, in which she is to portray a bird in a gilded cage set over a fire. As crazy as this may sound, there is evidence that the Romans would dress condemned criminals up and force them to play some theatrical role as they were executed; check out this blogpost and the scholarly article upon which it is based.)

Tiana escapes her execution, in the process immolating the entire Thesian ruling class, and then discovers a magical artifact, a skull in a box, in the tunnels under Thesia's capital city. While she is making her way back to the port, dealing with soldiers hunting for the artifact as well as a dangerous witch as she goes, her foster father Caranga and the crew of her ship, Vixen, are making themselves the new rulers of Thesia. Shortly after Tiana and Caranga are reunited, while they are trying to consolidate their rule over the kingdom, an international naval task force arrives to restore their idea of order by overthrowing the new pirate government. Tiana and company escape by sailing the Vixen down some river rapids no ship has ever successfully navigated before.

Tiana is informed by the intelligence apparatus of her native country that the magical skull is somehow connected with the secret ruler of the world whom those in the know call "the Owner." The Owner lives on a distant island and periodically requires tribute from the mortal kings of the world in the form of particular magical items and shiploads of attractive women, four hundred women a year! (The fact that Tiana and Caranga, who spend all their time at sea and in ports talking to other sailors, haven't heard of this guy, who receives shipments of esoteric valuables and female slaves from all corners of the globe multiple times a year, and who has destroyed "vast armadas" sent to bring him to justice, is something of a plot hole.) The Owner sends a heavily armored dragon to burn up the Vixen, but Caranga spots a vulnerable patch on its belly and, Bard-the-Bowman-style, kills it with a thrown harpoon. Then Tiana contrives to have herself captured by the Owner's mysterious henchmen, the "Moonstalkers," and added to the cargo of comely women aboard one of his mysterious black ships, bound for his secret island HQ.

The character of Tiana presents a problem to the authors (and to readers.) She is the best at swordfighting, the best archer, the best at detecting poison, the best at picking locks, the best at climbing, a skilled surgeon, and able to beguile any man she meets with her body, so she is never in any kind of physical danger. Tiana is also never in any kind of psychological danger. She lacks any kind of strong motivation or goal that might be frustrated (she just seems to care about stealing stuff and selling it and only gets involved in all these crazy missions because wizards manipulate her) and she doesn't feel any need to prove anything to others or to herself--the authors actually make a joke out of her boundless self-confidence and self-esteem. Tiana has convinced herself that she never feels any fear, she has absolutely no doubt that all the killing and stealing she does is fully justified, and she is constantly complimenting herself on her looks. It is hard for readers to care about or identify with such a character, and it is hard for the authors to generate any tension in a narrative about such an invulnerable character's adventures. This might not be much of a problem in a short and brisk piece of fiction, or a piece of fiction meant primarily as a comedy, but in total War of the Wizards is like 600 pages and (I believe) is trying to provide "thrills and chills."

Offutt and Lyon solve this problem by surrounding Tiana with, and devoting large portions of the books to, characters who are more psychologically complex and more fallible than their lead character. Pyre, Bardon and Caranga all face serious psychological challenges, so I could put my feet in their shoes, and I was never sure they would have happy endings, so I was genuinely curious as to how their stories would work out.

Interspersed with the chapters about Tiana's adventures are chapters about the adventures of another of these memorable secondary characters, a knight. In a little homage to medieval literature, the authors describe this dude as "dolorous," and well they might! Pyre, one of the world's greatest wizards and inveterate foe of Ekron, manipulates the knight in such a way that he guides him to his castle, and then erases his memory. The knight doesn't know his name or nationality or anything! Pyre even puts an enchantment on him that makes it impossible for anyone to see his face, including he himself--when he looks at a mirror or other reflective surface, he just sees a blur! Pyre teleports the Grey Knight (as he takes to calling himself) across the continent, putting him in charge of an attack force of Northerners (Viking-type guys) and sending him off to the nation of Naroka, where Ekron is based. In The Eyes of Sarsis Pyre equipped Bardon with a magical devices, and the sorcerer similarly provides the Grey Knight with a box of goodies that will help him in his dangerous mission. The knight uses these goodies to infiltrate the court of the king of Naroka, as well Ekron's own forbidding castle, to gather valuable information, and then to sneak aboard the black ship upon which Tiana is held captive.

The black ship is crewed by the living dead, and the women aboard are confined to tiny filthy cells where they eat maggoty rations; Matrix-style, these beauties suffer the illusion that they are inhabiting luxurious apartments and supplied with gourmet meals! Of course Tiana is able to see through the illusion and sets about hijacking the ship, a task she accomplishes with the aid of the Grey Knight. (War of the Wizards is full of the undead and full of illusions, and it is not just evil magicians using such sorcery to bedevil Tiana--a friendly wizard like Voomundo used animated corpses to aid Tiana, and much of the magic provided by Pyre that smooths the Grey Knight's way consists of illusions.)

In the last hundred pages or so of Web of the Spider things take an apocalyptic turn. For one thing, Tiana, who has been fending off men unworthy of her throughout the trilogy, falls in love with the nameless and faceless Grey Knight and the two are joined in a rough and ready impromptu wedding ceremony. Equally revolutionary, on the Owner's island the newlyweds--and the Grey Knight's father-in-law Caranga, who arrives in the Vixen, bearing that magic skull, not far behind the black ship--precipitate a cosmic battle between good and evil of world-shattering proportions. In a perhaps shopworn bit of imagery, the battle is manifested as an enthroned white-clad and white-haired man seated across from a throne inhabited by a shadowy blackness, between them a chess-like game board with pieces in the shape of Caranga and other pivotal individuals and objects. Should the darkness win the game, the world will be enslaved, but, because all humans carry within them at least some small proportion of evil, in the event that the figure representing pure Goodness triumphs, all human life will be extinguished!

(I wonder if all this imagery and cosmology owes anything to Michael Moorcock's Law and Chaos and Balance themes, seen in his many Eternal Champion stories. Also, there is a scene in which Tiana explains to another character how to correctly pronounce her name, which reminded me of the scene in Fritz Leiber's Nebula-award-winning 1970 story "Ill Met in Lankhmar" in which Fafhrd explains to the Gray Mouser how to pronounce his name.)

Fortunately, our heroes figure out how to assure the battle is a stalemate, and then, when Ekron launches his final attack, Tiana, with her detective brain solves the mystery of who the Grey Knight really is and with her quick wits tricks Ekron into destroying himself. The status quo of the world and the human race is preserved, and our heroes get a happy ending.

The apocalyptic ending goes on a little too long (the final battle in The Eyes of Sarsis was better), but I enjoyed Web of the Spider and the entire War of the Wizards trilogy. The magic is interesting, most of the action scenes are entertaining, and the three books feel like the work of people who put some serious effort into writing them derived some pleasure from their work. One telling piece of evidence is the minor characters: Offutt and Lyon make them, all the many monarchs and aristocrats and lesser witches and magicians whom Tiana exterminates as well as her friends and supporters, interesting by providing each with some memorable personality quirk or motivation or relationship with some other character. I recommend Web of the Spider as well as its predecessors to sword and sorcery fans as a fun read.