I enjoyed my recent look at the 1950 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories with Leigh Brackett's "The Dancing Girl of Ganymede" and Henry Kuttner's "The Voice of the Lobster," so, to take a break from my rereading of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, I propose spending some time reading more stories by Brackett and Kuttner from Thrilling Wonder (we might end up checking out some Thrilling Wonder contributions by Brackett's husband, Edmond Hamilton, as well.)

Today we'll just focus on Leigh Brackett, with three stories that appeared in TWS (as we fans call it) in 1949 and 1950. If you are really in the mood for some Brackett TWS action, you can also read my scribbles about an earlier Brackett story from TWS, 1944's "The Veil of Astellar." (Even better, read all four magazines at the internet archive.)

"Quest of the Starhope" (1949)

"Quest of the Starhope" appears in the same issue of TWS as Hamilton's memorable "Alien Earth" and Ray Bradbury's "Concrete Mixer," which I am making a mental note to read soon.

Bert Quintal is a man driven by ambition, a man without a heart! He was born in the slums of Chicago, signed on to the crew of a space ship at thirteen, and has fought his way to fame and fortune, never having made a friend, never having felt love! He made his money and won his reputation by capturing alien creatures on Venus and Mars and shipping them back to Earth for display to what Brackett calls "gaping mobs." This is a dangerous career, but early on Quintal found his ace in the hole, a tiny little alien with psychic powers. Quintal threatened to kill this little guy's wife, so the little guy, whom Quintal calls Butch, became his lieutenant. Butch can sense and read minds at long range, and send telepathic messages at short range, so he sits on Quintal's shoulder, hidden under Quintal's hood, and helps Quintal sneak up on creatures, avoid ambushes, and talk to aliens. Butch has saved Quintal's life many times, and made possible the ruthless trapper's string of successes.

Quintal is not satisfied by wealth and fame--he is restless, always looking for new creatures to capture. So today he is anxious, worried, even scared, as it looks like he has captured every worthwhile creature on Venus and Mars, and current technology isn't sufficient to take a ship beyond the asteroid belt. With no more goals to pursue, life is going to be miserable.

But wait! Quintal, flying over the desolate surface of Mars in his one-man scout ship, the Starhope he spots something moving in one of the old abandoned cities that dots the Martian landscape. Once, Mars was the home of numerous highly advanced civilizations, but a series of catastrophes, earthquakes and the like, caused their downfall long ago. Quintal lands to find that this city is half buried in sand and inhabited by the short and barbaric descendants of one of those highly advanced races. Quintal plans to capture some of these degenerate Martians to put in cages and display to those mobs back on Earth, but when he explores a buried factory, he discovers a far greater boon--those ancient hi-tech Martians had just developed a process to produce anti-gravity metal when the environmental cataclysm buried their cyclotron and foundry! If Quintal can get the factory working again he can build a ship that will enable him to fly to Jupiter, to seek out new life and new civilizations to put in cages to bring back to Earth!

With the essential aid of Butch, he uses trickery and threats to get these Martians, who are scared to go into the factory because it might get buried again at any moment, to put the cyclotron and foundry back into operation and to modify his one-man ship so he can fly it to Jupiter. They are almost finished with this task when a sandstorm comes and kills most of the Martians, just as they had feared! Butch is guilt-ridden, and works with the few surviving Martians to overpower Quintal. They paralyze the hunter, and then send the freshly upgraded Starhope on a one-way mission to deep space, a trip on which the immobile Quintal will soon die of dehydration. The factory being buried again, it will be a long time before anybody from Earth will be able to get his hands on some anti-grav metal, pushing back the day on which the people of Jupiter and the rest of the outer planets will run the risk of being enslaved and humiliated by Earthmen.

This story isn't bad. I speculate that it is this kind of anti-imperialist story, with sympathetic alien victims of Earthmen's exploitation and the suggestion that technological breakthroughs lead to oppression, that lead Michael Moorcock to gush about Brackett and dub her "one of the true godmothers of the New Wave." (See Moorcock's essay 2000 essay "Queen of the Martian Mysteries."

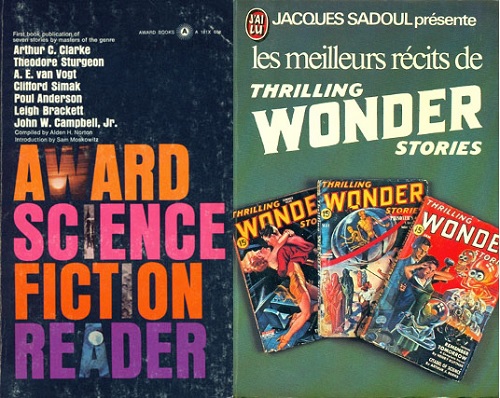

"Quest of the Starhope" was republished in a 1964 reprint magazine, Treasury of Great Science Fiction Stories, and in a 2007 volume from Haffner Press, Lorelei of the Red Mist: Planetary Romances.

"The Lake of the Gone Forever" (1949)

|

| On the cover we see depicted the tragedy of Rand Conway's parents |

When our protagonists get to the White City on icy Iskar, the native Iskarians, tall beautiful people armed with spears who hang skins in front of the doorways of their homes because there is no wood on Iskar, aren't too happy to see them. In fact, when Rand, Esmond and Charles Rohan are standing before the city gate, the natives, in the halting English they learned from Rand's pater, threaten to kill them if they don't leave. Esmond and Rohan want to negotiate their way in, just what you'd expect from an academic and a businessman, people who make their way in the world via words and horsetrading, but Rand, like the Iskarians, knows the way the universe really works. He tells the Iskarians that their ship is armed with high tech weapons, and if anything happens to them, the ship's crew will raze the whole city! This gets the three of them in, but all the crewmen and Marcia are left behind, along with most of their firearms (Rand keeps a stunner secreted in a concealed holster.).

The natives act like they are going to lynch the three Earthers, but their leader, an old geez ("cragged" and "gnarled," and "strong as a rock") called Krah stops them. Apparently Rand Conway's father did something to piss them off, and they have not forgotten it. Luckily, Rand and company don't let on that Rand is the descendant of the man the Iskarians call "Conna."

The people of the White City have very strong ideas about gender norms; Brackett tells us "Conway noticed that the women and children did not mingle with the men," and provides other stark examples. Conway, Esmond and Rohan are given sleeping quarters in Krah's house, and during the night Marcia Rohan, all by herself, worried about them, comes to the city, and the women of the city, seeing a woman in mannish clothes walking around unchaperoned, stone her! Fortunately, Krah intervenes before Marcia is maimed or killed.

In Krah's household is an attractive woman, Ciel, who tries to make contact with Conway--this chick remembers "Conna" with admiration and sees how Marcia acts among the Earthmen, as if she is their equal. Ciel wants Rand to take her to Earth, a place where women, she believes, "[are] proud like man....Free." (It seems that one reason the Iskarians are resentful about "Conna" is that he put ideas of gender equality into the heads of a few women like Ciel.) Besides this, Ciel is smitten by the rough and tough Rand, who makes bookworm Esmond and merchant Rohan look like wimps--Rand is almost like an Iskarian himself!

Conway smiled. He liked her. They were the same kind, he and she--nursing a hopeless dream and risking everything to make it come true.Rand agrees to take Ciel to Terra if she'll help him sneak off in stolen native clothes to find the Lake of the Gone Forever his father talked about. Cunning Krah, however, knew Rand was Conna's son all along, and he and his five sons are watching. They follow Rand and Ciel to the black lake that lies on the other side of some challenging terrain. By the Lake, Conway and we readers come to learn the truth of Conway's life.

The Lake has strange powers--if you look upon its black surface it records your moving image, and if later some person comes to the Lake and gazes on it while thinking of you, he will see that recorded reflection run like a movie. Conway's father, "Conna," and fell in love with a woman--Krah's daughter--and tried to settle down in the White City, but the potential financial value of whatever mysterious substance gives the Lake its crazy psychic influence gnawed at his mind and finally overcame all his inhibitions. Conway watches a recording of his father's disastrous attempt to gather a sample from the Lake--disastrous because Rand's mother, trying to stop Dad from defiling the sacred Lake, fell in and was lost forever. Brokenhearted, Conway's father left Iskar with his son, never getting over his loss and his guilt.

Conway came to Iskar to do what his father failed to do--steal a sample of the Lake himself and thus get rich. But seeing the story of his mother's death, realizing he is half-Iskarian, and falling in love with an Iskarian woman just like Dad did, he decides he wants to stay on Iskar and marry Ciel and live like a barbarian, throwing aside his career as a guy who pilots spaceships for a career hunting beasts with a bone spear in year-round subzero temperatures. Krah--his maternal grandfather-- accepts his repentance and everybody lives happily ever after. Even Ciel accepts this, even though just a few hours ago she was saying she would murder Rand if he went back on his promise to bring her to Earth. I guess she figures an Earthborn husband will treat her more as an equal than would a native-born Iskarian husband.

(Conway has kept the Lake a secret from the rest of the expedition, so I guess there is no risk of the Rohan clan trying to steal a sample from the Lake.)

Obviously "The Lake of Gone Forever" has the same sort of anti-imperialist themes we saw in "Quest of the Starhope"--the less these Isakarians have to do with Earthpeople and their technology and culture, Brackett suggests, the better. But this story is more nuanced and more complicated, bringing in other themes. The main points of the story seems to be that your rightful place in the universe is in your native culture--not the culture you grew up in, necessarily, but the culture of your blood (again and again Brackett gives hints that Rand is in tune with Iskar, even though he grew up on Earth)--and that you shouldn't tinker with your culture's rules or disaster will result. Brackett seems to side with the barbaric sexist culture of Iskar over the capitalistic, scientific, liberal culture of Earth represented by businessman Rohan, egghead Esmond, and liberated Marcia--for the crime of being women who act independently, Iskarians beat Ciel in one scene and stone Marcia in another, and Brackett doesn't portray those who performed this violence being punished in any way. In the end Rand chooses to abandon high tech and liberal Earth and embrace the low-tech savage culture of his mother's civilization, while Ciel, who wanted to escape the sexist culture she was born into after learning there existed a less sexist one, decides to stay. Damn!

I have to say the themes of this story have me shrugging my shoulders--I certainly wouldn't want to spend my life wearing animal skins instead of my J. Crew sweaters and catching my food with a bone javelin instead of a credit card. And I was cheering on Ciel for wanting to ditch home and build a life of her own, and was kind of let down to see her stuck in that ice-covered city where there was no wood or paper or pizza place. Brackett's attitude doesn't comes as a surprise, though. In preferring barbarism to civilization she is following in a long tradition of which her antecedents in the sword fighting adventure game Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard are exemplars. Maybe her romanticizing of the embrace of one's ethnic heritage is a response to what some have seen as the alienation and deracination attendant with modern urban life, depicted, for example, in T. S. Eliot's early work. As for the gender role stuff, we saw Brackett sympathizing with traditional ideas about gender roles in Alpha Centauri or Die!

I have to respect Brackett for not sugarcoating her message and having Iskar be some kind of utopia--remember when Chad Oliver had a guy leave a spacefaring civilization to join a Plains Indian tribe? Old Chad made that hard-to-swallow choice go down a little easier by telling us that the Indians had (somehow) achieved immortality! Cripes, that was lame. Brackett here doesn't come up with some totally bogus reason that living like a savage is better than living like a city slicker--she tells you should embrace the ways of your people because they are the ways of your people, even if your people's ways suck.

There are some little plot oddities to "The Lake of the Gone Forever" that had me scratching my head. Conway's father somehow got to Iskar all by himself, but his son felt the need to get the support of a rich guy? (Obviously Brackett needs the nerd, the lucre-lover and the women's libber there to serve as contrasts to the Iskarians, but you sort of have to wonder why Rand didn't just go to Iskar himself if his father had the means to do so.) Another thing is that the men of the White City are all described as tough warriors, and it is implied they have a whole tradition of honor based on fighting with spears, but who are they going to war against? We never hear about any other polities on Iskar, or bandits or whatever. Maybe Brackett should just have said they were tough hunters.

(I've given up wondering why Earth people in these old SF stories can have children with aliens, something I used to complain about; in particular I recall grousing about this in Chad Oliver stories--I guess I kind of use poor Chad as a punching bag on this here blog. Now when I read these stories in which Earth people and aliens have the hots for each other I just assume what some of them make explicit, as Hamilton does in the Captain Future stories, that humans are not native to Earth, that long long ago some aliens seeded the galaxy with human spores or there was once a human empire that spread across the galaxy but decayed leaving no trace of its existence or something like that, and so people from different solar systems are as genetically compatible as people from different Earth continents.)

Whatever you might think of this story's politics, it is thought-provoking and a decent read, and it has lots of stuff about icy scenery and Rand's dreams and psychology that people might like. Perhaps because of its provocative look at an intersection--one might say a collision--where modern attitudes about imperialism and gender norms meet, it has been included in two different anthologies of SF by women which have gone through multiple editions, Pamela Sargent's More Women of Wonder and Richard Glyn Jones and A. Susan Williams's The Penguin Book of Modern Fantasy By Women.

"The Citadel of Lost Ages" (1950)

"The Citadel of Lost Ages" appeared in an issue of TWS whose editorial is a long celebration of women SF authors and how they have improved the SF field and how things are so much better today in 1950 than in the benighted past when there was so much sexism in the SF field.

A dude wakes up in a tiny dark room with a little slit of a window. He doesn't remember his name or where he is or what is going on! He looks out that window and sees a vast city of stone, wood, and mud buildings, of market squares and throngs in the streets riding horses and leading other beasts. Somehow he knows, though, that this city once had towering metal skyscrapers. Another weird thing--the Sun in the sky doesn't move, and he somehow knows it should!

A pretty girl with a face somehow reminiscent of a cat's opens the heavy metal door on our dude's cell and he grabs her, covers her mouth, threatens to kill her if she cries out. (Brackett's work is full of this kind of sexualized violence.) She is disappointed that he doesn't recognize her, and gives him and us readers tantalizing clues about the crazy world in which he finds himself--she is a temple slave, offers that she hates the "Numi," and is going to help him escape!

The young woman, Arika, leads our dude, whom she calls "Fenn," through the secret doors and passages of this huge stone building, the temple in which she is forced to work. Along the way we learn that the Numi are a semi-human people who have somehow conquered the Earth. They are tall and furred and muscular--when Fenn spies some of them Brackett tells us they are "beautiful," their bodies "more like the bodies of lions than men," but not at all beast-like, in fact "they seemed to Fenn to be above men like himself as he was above the brutes."

Hiding in the temple's tomb, Arika and Fenn listen as the queen of the Numi comes by to talk to her dead husband, who is encased in a crystal column. She complains that "the human cattle" are growing insolent. After she leaves, Fenn has to kill a Numi priest who stumbles on our heroes, and we get more sexualized violence as Fenn grapples with the muscular cleric, rolling around on the floor with him, "his thighs locked tight around his loins," the Numi scratching and drawing blood, Fenn biting the priest and tasting his alien blood as he struggles to crush the life out of him. Zoinks!

Arika leads Fenn out of the temple into the slum of huts where live the humans who are the Numi's cattle and the half breeds like Arika, whose father was a Numi, who are their slaves. (Like Rand Conway in "The Lake of the Gone Forever," Arika here in "The Citadel of the Ages" is a half breed who embraces her maternal ethnicity and rejects her father's imperialistic people.) The Numi have all kinds of mental powers, and half-breeds like Arika have similar, though weaker powers. Arika uses her powers and drugs to revive Fenn's memory, and we learn the astonishing truth of the fate of Earth in the 1980s!

Like in a 1929 Edmond Hamilton story, in the '80s a black star passed through the solar system, causing civilization-destroying events on Earth, earthquakes and tsunamis and so on--the Earth's speed of rotation even changed, so that it always shows the same face to the sun. The eggheads saw the dark star coming, and knew it would make a mess of this big blue marble, and so the authorities built a Citadel in the Palisades that would survive the cataclysm and stored within it the knowledge and power with which to rebuild society! Over a thousand years later the Numi heard legends about it, and one of their head priests, RhamSin, used his mental power on a captive human to reach back through his racial memory and pull forward the consciousness of a 1980s New Yorker named Fenway who had been in the Citadel just after it was completed. But Arika has beaten RhamSin to the punch, extracting the location of the Citadel from Fenn before the Numi priest had an opportunity to do so!

|

| "The Lake of the Gone Forever" and "The Citadel of Lost Ages" both appear in The Halfling and Other Stories |

Malech looks like a Numi and has lots more trouble passing than does she when the three meet some outlaw humans and need their help. Presumably Brackett based Malech's tragic life of being rejected by both humans and Numi on the plight suffered by multi-racial Americans who were never fully accepted by the communities of either of their parents. Over a dozen of the desert outlaws join Fenn's party as they ride cross country towards the East Coast, and as the days and weeks pass, Malech becomes more and more alienated from the group. At the same time, an expedition led by RhamSin is pursuing them and gradually closing the distance.

The expedition crosses into the zone of darkness where the sun never shines, a place of cold and ice. The men are amazed by the sight of the stars, which they have never seen before. This strange milieu challenges their sanity, and the cold threatens their health--only half the adventurers make it to the Atlantic coast where Fenn opens up the Citadel, a vast subterranean warehouse with more square feet than the Empire State Building full of books and films and models, all the knowledge and art built up by man over the centuries before the destruction wrought by the dark star. But those who stocked the Citadel decided to leave out the machine guns, grenades, and flame throwers their descendants could have used to overthrow the Numi--idealistically, they left no weapons in this monument to humanity's culture and learning!

RhamSin's party lays siege to the Citadel, and Malech betrays the humans and his sister--RhamSin has promised to accept him as a full Numi if he helps them take the Citadel. There is a bloody fight, but in the end Fenn remembers something about the Citadel that gives the humans an edge in the fight. As the story ends, we can be confident that, with the knowledge in the Citadel, mankind will throw off the tyranny of the Numi and build a new civilization. If you are some kind of optimist, maybe you can tell yourself that the relationship between Fenn and Arika presages some kind of reconciliation and decent modus vivendi between us mundanes and our cat-like betters.

A pretty good story. Besides in a few American Brackett collections, "The Citadel of the Ages" has also reappeared in some foreign anthologies.

**********

These are entertaining adventure stories about driven men, men who are on their own and trying to make a life for themselves in the universe, trying to bend the universe to their wills and not always doing the right thing. The stories all include fun SF elements like anti-grav, lost races, and weird mental powers, as well as tense violence, and Brackett adds levels of psychological, political and sociological interest by introducing issues of cultural and ethnic identity, issues she resolves in ways liberal and libertarian types won't necessarily find congenial. Thumbs up for all three, though the first I read, "Quest of the Starhope," is not as complex or effective as the later two, "The Lake of Gone Forever" and "The Citadel of Lost Ages."

More TWS in our next episode!