In 1957, Judith Merril published, as the last section of her anthology SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy: Second Annual Volume, a long alphabetical list of 1956 stories which hadn't quite made the cut for inclusion in the anthology but which she thought worthy of recommendation. In 2023 and 2024 we have been reading selected stories from that list, starting with the A authors and working our way through the list until today we hit T and proceed beyond. We've got three stories today, and I will also note that we've already read the story by a U author that Merril recommends for 1956, Helen Urban's "The Finer Breed."

"Into the Empty Dark" by E. C. Tubb

First up, E. C. Tubb, creator of Dumarest of Earth. "Into the Empty Dark" debuted in

Nebula Science Fiction ("Voted Britain's Top Science Fiction Magazine") and has never been reprinted.

"Into the Empty Dark" is serious old-fashioned science fiction, an attempt to realistically portray space flight in the near future. In the universe the story describes, mankind has only been travelling between the planets for twenty years, and journeys between the inner planets are slow, dull, and strain everybody's mental heath. The ships must strictly follow predetermined courses to get to their destinations, as they lack the fuel, sensors and communications equipment to safely or profitably make course corrections on the fly. So when Captain Strackland's ship gets an SOS from another vessel, one which has been hit by a meteor and thrown off course, there is not a hell of a lot Strackland and the two men who make up his crew can do to help them.

Tubb does a good job describing the way space flight work in this story, and a decent job describing the psychological effects on the spacemen as they face crisis and tragedy in the void between the Earth and Mars. The story's tone and atmosphere, and all the little details, bring home the idea that space travel is unglamourous and tedious, but still dangerous, and Tubb doesn't talk much about how mankind has benefitted from exploring and colonizing the solar system. The people on the other ship die, there being nothing Strackland and company can do to help them, and Tubb suggests Strackland and his crew will suffer lifelong psychological scars from the incident.

I like it.

"A Little Thing for the House" by F. L. Wallace

Over the years we have read two stories by Wallace,

"Student Body," and

"Big Ancestor," and thought them relatively good. This story isn't bad, either, though it seems it has never been reprinted.

"A Little Thing for the House" is another of those stories that warns you utopia is going to suck and that to flourish people need some kind of challenge, need some kind of productive work to do. It depicts a future in which computers and robots do everything, and people are actually forbidden from performing any sort of real work, even such things as cooking their own food, much less building or operating or repairing machines. The computers allow people to be poets, artists, athletes and scientists, but the story suggests that since most people lack the talent to be truly successful at such work, many are unfulfilled.

Our hero Holloway is an aspiring mechanic; as a child his great grandfather told him stories about the old days when people had to make their own way in the world instead of having everything handed to them, and how he (greatgrandpa) had been a fixer or tinker, a guy who repaired tools and machines and did odd jobs. All his life that sort of work has appealed to Holloway, who has a mechanical mind but doesn't want to be a scientist--he likes to work with his hands. As the story begins, Holloway has managed to find a person, the married woman Madge, who has somewhat similar aspirations--Madge wants to bake and cook like people did in centuries past, not just tell the kitchen machines what to make and have it spat out of a little door at her. Holloway knows how to alter the kitchen machines to allow her to turn them off and on at will, so she can bake her own cookies (interestingly, in this 1956 story Wallace spells the singular "cooky") or whatever she wants. Accomplishing this task will take a while, so Holloway moves in for a few days--Madge tells hubby (who goes to an office to play a stock market simulation set up by the computers to fill up his time) and daughter Alicia that Holloway is an old friend just visiting.

Alicia is an exhibitionist who chases men and wishes she lived in the days when she could be a courtesan and bang a succession of guys. She flaunts her "hard young" body at Holloway and flirts with him briefly, but when she realizes how unlikely he is to become famous she turns her attention to another guy who starts showing up, the new local counsellor, a young guy taking the place of the old geezer who just retired. These counsellors are sort of like commissars who help people figure out what to do with their leisure-filled lives and also keep an eye out for people who might illegally be doing real work. This new guy is pursuing rumors of a "maladjusted" citizen, and Holloway is his prime suspect, but he gets a little distracted by Alicia's attentions.

When Holloway has reason to believe the counsellor has his number and is about to arrest him, the would-be tinker sneaks into the central computer for his city and puts to use all his mechanical skills to threaten the computer and compel it to loosen the regulations and allow people more leeway in which they can do productive work. After his success, Alicia throws herself at Holloway (he is kinda famous now) but he rejects her--he has another woman in mind. I figured this would be Madge, with whom he has something in common, but instead it is some woman whom Wallace hasn't mentioned before, Anne, I guess Holloway's wife or fiancé or something. We are told Anne has patiently waited for Holloway while he pursued his risky campaign to become a working mechanic in a world in which that is a crime. Is this Wallace telling us that the ideal woman is one who stays in the background and silently supports her man? Was Anne, who is only mentioned in one paragraph, a late addition to the story?

This story is OK, maybe marginally good. Feminists won't like that the active women in the story aspire to either bake and cook or become promiscuous groupies and that the woman the hero chooses as a romantic partner is neither of those risk-taking outgoing women but instead a woman who passively waits for him. Personally, I have to question the wisdom of introducing a new character on the penultimate page of a 29-page story--seeing Holloway take up with either horny little Alicia or accomplice-in-rule-breaking Madge, or just passing on women altogether to focus on his libertarian activist work, would have been more satisfying. But in general the themes, pacing, and structure of the story work; "A Little Thing for the House" is never boring or annoying, and I found it entertaining enough--in particular, it is interesting to see a depiction, over 60 years ago, of a world in which it is not necessary to work and so men become immersed in computer games and women devote themselves to using their sex appeal to win fame.

"The Asa Rule" by Jay Williams

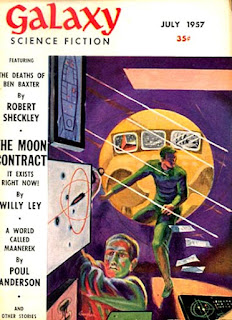

"The Asa Rule" debuted in the same issue of

F&SF that included Robert Bloch's

"All on a Golden Afternoon," which I declared "the Platonic ideal" of a Bloch story when I read it way back when. For some reason, on Merril's honorable mentions list in

SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy: Second Annual Volume, the source for the story is listed as

The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction: Sixth Series, so we'll read it there to ensure we are experiencing the text Merril is recommending.

(The boys down in Marketing want me to post a link to my blogpost about the Poul Anderson, Ted Sturgeon and Avram Davidson stories in The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction: Sixth Series, so here it is.)

Lucy Ironsmith is an equatorial Martian with pale green skin, silver hair, crimson eyes, and a slender body, and is so striking that when Terran Leonard Jackson first sees her he spills his drink and the service robot has to roll in to clean him up. Leonard has come to Mars to study the ecosystem of the Martian tundra, and Lucy is going to be his assistant, teach him Martian culture and help him avoid offending the locals out of ignorance of their customs.

The Martians, we readers of stories recommended by Judith Merril are not surprised to learn, are better than humans--closer to nature, more peaceful, less aggressive. Lucy says that to Martians, Earth's history seems "bloody, senseless, and disagreeable." Leonard suggests that some humans are like Martians, naming "the Hopi, the Navaho, some Polynesian people, some of the Africans...," you know, peaceful and friendly, and that the rest of the human race is slowly catching up to those admirable demographics, learning to be peaceful. Lucy admits that Martians used to fight, but that was long ago; for two thousand years Mars has had its own United Nations, something which Earth has only had for less than 100 years.

Leonard wasn't sent to Mars to flirt with a green girl and explain to her that not all Earthers are as bad as white people, however; his job is to figure out a way to deal with the deadly swarms of insects that make the Martian tundra hard to cultivate. The clouds of bugs leave the villages of the local primitives, the grey-skinned, flat-nosed, semi-nomadic Asa, alone, but, when in the tundra, Martians of Lucy's green ethnic group, the Hvor, have to carry with them special protective suits to don should a swarm appear. The Asa are even more in touch with nature than Lucy's people, and "live by a rigid rule in which they must love and assist each other and even their worst enemies." The Asa hold the bugs to be sacred, and refuse to explain to others their method of keeping them from attacking. (You'd think that "assisting others" would include telling the Hvor, if not us deplorable Caucasians, how to avoid getting killed by the bugs, but I guess not.)

Monthly, the women of the Asa hold a secret ritual honoring the insects, a ritual no man must witness. Leonard sneaks off and spies on the ritual without informing Lucy or his Terran superiors, who specifically told him not to do this. He is caught, and, I guess having forgotten to identify as transgendered, is taken by the Asa to a special boulder out in the tundra, "given to" the bugs to suffer their judgement. When Lucy finds out she is pretty upset, being in love with Leonard, and even whips out a gun and threatens the Asa tribal leaders, to the amazement of the human accompanying her--he has never seen a Martian acting so aggressively before. Luckily, before anybody gets blasted, Leonard appears. He explains that after the Asa left him, the insect swarm arrived and started biting him, but Leonard, gosh darn it, is such an inquisitive scientist and such a nice guy that, even while they were biting him, he found the bugs fascinating and even "cute." As soon as he realized how adorable the venomous insects were they stopped biting him. You see, the bugs can sense hate and love, and they only bite haters; people full of love they leave alone.

The story ends as Leonard and Lucy are on the brink of sharing their first kiss.

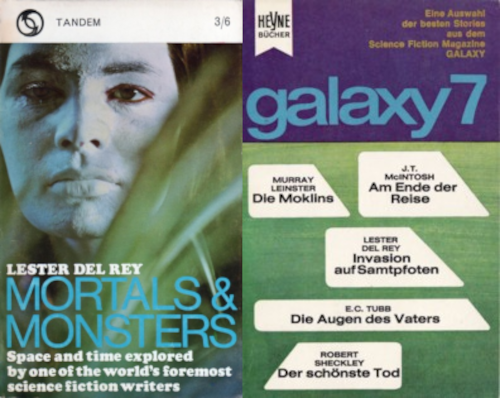

"The Asa Rule" is written in a simple and childish style that matches its one-note characters, sappy message and all the little lectures on the UN and diversity and the environment--the story reads like a kid's book meant to mold your little tyke's personality and opinions. Thumbs down! I guess I should have expected this, as when I looked at the page on Williams at isfdb it appeared that most of his SF output consisted of juveniles about kids learning to cooperate or marveling at the fascinating culture of the Native Americans, but I did not (in fact, when I realized this was the story with the sexy green girl on the cover of both the magazine and the hardcover edition of The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction: Sixth Series, I got hopeful.)

**********

It is easy to see why Merril included these stories on her list; the Tubb and Wallace express skepticism of technological progress in the context of stories that also say something about human psychology, and while the Williams is like a propaganda piece directed at nine-year-olds, it promotes aspects of what I take to be Merril's own ideology.

We've been plugging away at this 1956 SF a la Merril project since March of last year, and the final stage of the journey approaches! Stay tuned for the final episode of this caper, and cross your fingers in hopes the last stories we read from Merril's list are more like today's contribution from Tubb than that from Williams!

.jpg)