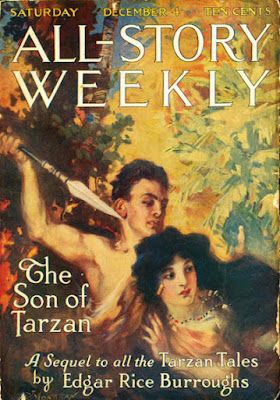

One of Tarzan's enemies in the second Tarzan book, The Return of Tarzan, and the third, The Beasts of Tarzan, was Russian freelance spy Alexis Paulvitch. In the first chapter of The Son of Tarzan we learn that, after fleeing from the invincible Lord Greystoke in The Beasts of Tarzan, Paulvitch was captured by a tribe of cannibals who tortured and otherwise mistreated him for ten years, an ordeal with changed his looks beyond recognition and damaged his psyche. After escaping his tormentors Paulvitch meets Akut, a friendly ape, once a comrade of Tarzan's. Akut accompanies Paulvitch to England--the Russian does not realize, but we readers do, that Akut is looking for his old friend--and Paulvitch's most dangerous enemy,--Tarzan. In London Paulvitch makes money by having Akut perform in a music hall.

At the Greystoke town house we observe Lord Greystoke, Jane, and their son, Jack. Mom and Dad have kept from Jack the truth of his father's wild youth, Jane fearing that her son, who like her husband is exceptionally smart and strong, will feel the same itch her husband perpetually experiences--the urge to throw off his clothes along with all the encumbrances of civilization and risk his life in the jungle. In one of the crazy coincidences that fill to bursting the Tarzan books, or an instance of Lamarckian inheritance, Jack is indeed fascinated by accounts of primitive tribes, wild animals and European explorations of Africa, and when he hears about the performing ape he ignores his mother's wishes and takes in the show. Because he looks so much like his father, Akut immediately befriends Jack, to the boy's delight, and when Jack's father is reunited with his old anthropoid buddy there is no way to keep Dad's exciting childhood from the kid.

Paulvitch harbors a grudge against the Greystoke family and tries to murder Jack, but gets killed by Akut. Tarzan tries to have Akut sent back to Africa and Jack sent to a boarding school, but Jack is an insubordinate little rascal and, disguising Akut as a grandmother suffering some kind of social anxiety disorder--he hides "her" face with a lot of veils--accompanies the ape aboard a steamship in a private cabin. Almost immediately after they touch land on Akut's home continent, an American criminal tries to rob them and Akut, who is running up a real kill count, slays this crook. Rather than face a lynch mob or murder trial far from home, Jack impulsively decides to abandon civilization and take up life in the jungle with his ape friend.

In Chapter 5 (The Son of Tarzan has 26 chapters), Burroughs introduces us to a some new characters. One is Meriem, a ten-year-old French girl who three years ago was kidnapped by an Arab sheik kn own to all as "The Sheik," a bandit who sought vengeance on Meriem's father, an officer of the Foreign Legion who had brought to justice one of the Sheik's felonious relatives. Burroughs does not pull any punches in this book--the Sheik beats Meriem so much, and the "filthy" and "toothless" "old black hag" who is her nurse tortures her so much, that Meriem tells her little dolly that she wishes she was dead! Damn! There is a reward offered to anybody who can return Meriem to her farther, and when two Swedish poachers, cruel criminals themselves, spot Meriem while trying to work a business deal with the Sheik, they begin nursing a hope of getting hold of the girl and collecting the reward.

Jack and Akut march across plains and through forests for months, the ape teaching the English boy how to survive in the wild, and he takes to it readily, relishing a life of danger and violence. Among many exploits, we witness him ambush a black warrior and murder him with his teeth! Damn! Having stolen that poor bastard's weapons, Jack learns how to use them and use them he does, on various beasts as well as additional African tribesmen. Jack fully inhabits the moniker Akut bestows on him, "Korak," which means 'killer" in the language of the apes--he lives just as a forest carnivore loves, feeling no more guilt over killing an African warrior to steal his arrows than a crocodile feels guilt for killing a zebra for lunch.Over a year after landing in Africa, Korak stumbles upon the village where live Meriem and the man she thinks her father, the cruel Sheik. He rescues the little French girl from a beating and she joins Korak and Akut as a devotee of the tree-dwelling, beast-killing, ape-speaking jungle life; years go by and Meriem becomes nearly as good at jumping and climbing and tracking and killing as Korak. She grows into a beautiful young woman and Korak falls in love with her. She still sees him as an older brother, however.

Burroughs' novel is full of fighting and diplomacy among a host of different parties: tribes of apes, tribes of black villagers, tribes of baboons, the evil Sheik and his followers, the evil Swedes and their browbeaten black "boys," and others still; many people get captured and then escape captivity, either thanks to their own pluck and ingenuity or the efforts of rescuers. This is all pretty entertaining; among the highlights are Korak leading an army of baboons in an assault on a black village and Korak riding an elephant into the camp of one of the Swedes. The villainous Swede suffers some rough justice when the elephant recognizes him as the guy who slew his mate years ago.

Burroughs uses the same plot devices again and again. Many times throughout the novel, which is a hefty 222 pages, one character recognizes another who was important in his or her life many years ago, while the second individual does not recognize the first, leading to all kinds of melodramatic situations. Another oft-used plot device sees somebody, usually but not always Tarzan or Korak, by chance, stumbling upon a situation in which some person is about to get tortured or killed and delivering this vulnerable individual from a terrible fate.

Halfway through the novel, Tarzan, dressed in European fashion--complete with pith helmet and at the head of a party of his African employees, arrives, by chance, just in time to save a captive Meriem, who has been separated from Korak, from being raped by one of the Swedes. Tarzan brings Meriam, who doesn't know Lord Greystoke is Korak's father, just as Tarzan doesn't know this Korak guy she keeps talking about is his son, to stay with him and Jane and their retainers and their pack of dogs and all that at his African estate.

Months go by, during which Meriem at the Greystroke estate and Korak hanging around with baboons and elephants, each think the other dead. A visiting English gentleman finds Meriem irresistible, but he can't marry someone of such a lower social class, so he schemes to bring her to London and make a kept woman of her. The Swedish would-be rapist, whom Tarzan spared, arrives in disguise, (he shaved his beard) and insinuates himself onto the estate. He manipulates the English gentleman, hijacking the cad's project of carrying away Meriem to facilitate his similar designs. The Englishman is transformed over the course of all the betrayals, chases, captures, escapes and bloody fights that ensue--the true and honorable love for Meriem that blossoms within his breast, and the dreadful hardships he endures, like getting stabbed by a black guy and shot by a Swede and then shot again by an Arab, spur him to grow from a selfish, snobby and cowardly bounder into a generous and brave man. Of course, those hardships also kill him, but dying a good man is better than living as a scoundrel, right?The circuitous narrative of death, destruction, love and friendship that is The Son of Tarzan ends with joyous and tearful reunions as Tarzan and Jane see their son for the first time in years, and then Meriem in London is reunited with her French father, who we learn is a prince, making Meriem a princess! Like so many Burroughs protagonists, Korak has married a princess!

If 2014's MPorcius is to be believed, I was a little disappointed in Tarzan #3, The Beasts of Tarzan. But 2022's MPorcius is keen on #4, The Son of Tarzan. There is a ton of effective violence and animal action, but also quite a lot about the psychology and relationships of the characters--Burroughs depicts loneliness, lust, a passion for vengeance, guilt (or lack thereof), the tension that you feel when you want to live your life a certain way but that lifestyle puts a barrier between you and the people you love, and it all works. The Son of Tarzan is a big success.

So, thumbs up for this classic adventure story. And on to Tarzan #5, Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar!