|

| There's Chryseis on Pelias the erinye. Anderson's text actually mentions the precious stones she wears in her hair. |

Another thing you'll see if you look at a bunch of covers of Planet Stories is Poul Anderson's name. Let's check out three stories by Poul Anderson that appeared in 1951 issues of Planet Stories. I think these stories are among Anderson's least well-known, but as my regular readers are well aware, I like reading things that have been largely forgotten or which have gotten a bad reputation. I'll be experiencing all three of these tales of violence on other worlds on this very computer screen via the scans of the actual magazines in which they appeared that are freely available at the internet archive.

"Witch of the Demon Seas"

The January 1951 issue of Planet Stories actually includes two pieces by Anderson, the Dominic Flandry story "Tiger by the Tail" and the "novel" I'm reading today, "Witch of the Demon Seas," a cover story appearing under the pen name A. A. Craig.

"Witch of the Demon Seas" takes place on a planet where people live under a perpetually cloudy sky, fight with swords and bows, travel in sailing ships, live in castles and believe in magic (dismissed by some as mere "women's tricks.") The surface of the planet is covered in oceans, and the many maritime kingdoms ("thallasocracies") are based on groups of islands, their economies based on seaborne trade and slave raiding. The planet's human inhabitants come in many different ethnicities, including "blue-skinned savages" who serve as mercenaries in the armies of white kings. One such white empire is Achaera, land of brunettes and the most powerful and extensive of the kingdoms. The current king of Achaera is huge muscular Khroman. As our story begins, Khroman's most dangerous enemy, huge muscular Corun the pirate, has just been captured. Khroman's father, the previous king, conquered Corun's kingdom of blonde people, Conahur, and hanged Corun's father, the king of Conahur. Ever since this conquest, Corun has been a fugitive and a pirate captain, attacking every Achaeran ship and town he can get his hands on.

King Khroman's top adviser is his father-in-law, Shorzon the sorcerer. Khroman's wife died giving birth to their daughter, Chryseis. Trained by her grandfather, Chryseis is reputed to be a powerful witch, and is also perhaps the most beautiful woman on the planet! Anderson unleashes a lot of purple prose in this story, descriptions of landscapes and seascapes and the sky and how they make people feel, and we get elaborate descriptions of Chryseis's "chill sculptured beauty," "marble-white face," "eyes of dark flame," her clothes, her jewelry, her hair, etc. Chryseis also has a tame monster by the name of Perias, a flying reptile of a species the characters call "erinyes" or just "devil-beasts"-- you can see witch-princess riding Perias on the cover of the magazine. A pet monster, too? This is like my dream girl! Oh, wait, then there's the fact that she "ordered the flaying alive of a thousand Issarian prisoners and counselled some of the darkest intrigues in Achaera's bloody history." Every rose has its thorn, I guess.

It turns out that Chryseis and Shorzon have bigger fish to fry than just maintaining the power and glory of Achaera. The two magicians betray King Khroman, springing Corun the corsair from solitary after they have convinced him to join them on a quest that will shake the very foundations of this planet's whole civilization! Chryseis is a real femme fatale, using her beauty as a carrot ("I like strong men") and her pet monster as a stick ("If you say no...Perias will rip your guts out.")

Shorozon and Chryseis need Corun's guidance to get to the sea of the Xanthi, fish-people whose language lacks words for "fear" and "love" (but you better believe they have a word for "hate!") Corun, besides being a first-class hunk and a cunning sailor, is one of the few people who has spoken to the Xanthi and lived to tell the tale, and so is a perfect addition to the crew of the wizard and witch's galley, which otherwise consists of blue men, "a cutthroat gang" whose "reckless courage was legendary."

Anderson's story totally lives up to the sex and violence reputation of Planet Stories--"Witch of the Demon Seas" fulfills the expectations set up by all those covers of beautiful girls facing or meting out horrible deaths. On the month-long voyage to the black castle of the Xanthi, Chryseis and Corun become lovers, and, in a fight against the Xanthi, we get to see Shorozon use his magic and Chryseis shoot her bow and ply her sword. The sex-charged atmosphere, less-than-admirable characters and pervasive bloodshed reminded me of Leigh Brackett's work, which of course is a compliment!

Even though its full of dragons, sea serpents, witches and swordsmen, this is a science fiction story, not a fantasy. What the characters seek is not a pile of treasure, but knowledge. There's a scene in which Corun and another sea captain speculate about the possibility of using a chronometer and a sextant to determine a ship's position on the open sea (their world is too superstitious and low tech to accomplish these feats as of yet.) All the magic is in fact telepathic hypnosis and illusion, as Corun learns when he does some espionage work, listening in on the negotiations between his girlfriend and her grandfather and the rulers of the scaly Xanthi, themselves formidable wizards. Shorozon and Chryseis seek to join forces with the fish people and become as gods by enslaving the entire human race and using the masses of human brains as a source of psychic energy. With their own minds amplified by those of thousands of slaves, S and C think that they and the Xanthi sorcerers can explore the universe beyond the clouds, riddle out the mysteries of nature, and achieve immortality!

When he realizes Chryseis is a megalomaniac who is going to screw over every human being in the world, Corun leads the blue-skinned sailors in a raid on the Xanthi arsenal, where he lights a fuse leading to a stockpile of the Xanthi secret weapon, "devil powder" (you and I would just call it "gun powder.") The castle explodes during a running fight between the blue humans and the fish men--luckily enough blue people survive to man the galley. Shorozon is decapitated in the fighting, while Chryseis and Perias escape into the jungle, pursed by a vengeful Corun. Our hero kills Perias in a gory fight, gouging out one of the monster's eyes with his fingers--yuck!

With the monster dead, and Corun now immune to Chryseis's illusions, I was expecting the blonde muscle man to kill the witch in a cathartic Mickey Spillane-style ending. I was disappointed to find Anderson was giving us a happily-ever-after ending--the death of her evil grandfather and her monstrous familiar broke the hypnotic spell Shorozon had put on Chryseis so many years ago, when she was just a little girl. Chryseis was never really evil, she explains, she was just a pawn of her grandfather. Now that the spell is broken her true (sweet) character is liberated, as is her sincere love for Corun. As the story ends we are led to believe that Corun will marry Chryseis and eventually become the king of Archaera who unites Archaera and his native Conahur on a basis of equality and brotherhood.

There is maybe too much blah blah blah about the luminescence on the waves and the smell of Chryseis's hair and all that, and I consider the happy ending that absolves Chryseis of all responsibility for her crimes a cop out*, but "Witch of the Demon Seas" is a pretty good sword fighting adventure story. Robert Hoskins included "Witch of the Demon Seas" in his 1970 anthology Swords Against Tomorrow, and the Gene Szafran cover actually illustrates the story, depicting Shorozon's ship, a blue sailor, a fish man (with a face like a dog, unfortunately), and sexy sexy newlyweds Corun and Chryseis.

*Here's a question for all you feminists: which is more sexist, a story in which an evil woman uses her gorgeous body and superior intelligence to manipulate men in pursuit of becoming the world's greatest scientist and then gets killed by one of the men she manipulated, or a story in which a good woman is the pawn of a man who manipulates her to act against her goody goody nature and has to be liberated from this domination by yet another man?

"Duel on Syrtis"

"Duel on Syrtis" was printed in one of the most famous issues of Planet Stories, the one with Leigh Brackett's "Black Amazon of Mars" (one of the Stark stories) and A. E. van Vogt's "The Star Saint" (I reread this great story of a hunky superhero, told from the point of view of the "muggle" whom he cuckolds for the good of the community--ugh, even my thick skull is not impervious to that suffocatingly ubiquitous Harry Potter goop!)

In this story, Anderson portrays the human race as a bunch of jerks! When mankind colonized Mars they enslaved the native Martians, who look like skinny four-foot tall owls, if you can imagine such a thing. (There is a good illustration of a Martian on page 5 of the magazine.) They also hunted them for sport! Slaving and hunting Martians was recently outlawed, but successful interplanetary businessman and big game hunter Riordan hasn't bagged a Martian yet, and he goes to a secluded spot on the red planet where the authorities don't have everything locked up tight yet, to shoot himself an "owlie."

The Martian owlies are very challenging quarry because they are intelligent and psychically in tune with the flora and fauna of the desert landscape--bushes and rodents miles away can warn them of an Earthman's approach, and even attack the Earther. The Martian Riordan has set his sights on is a particularly tough nut to crack. Most Martians are now debased members of the urban lower class, but Kreega is one of the last wild Martians, living in an isolated ruin in the desert. Something like 200 years old, Kreega was one of the greatest warriors of Mars, a witness of the arrival of the first Earthman and a veteran of many raids on the human colonists before the signing of the peace treaties and amnesties now in force. Along with a hunting dog and a hunting bird, Riordan sets out to hunt this wily and venerable Martian hermit.

Anderson gives us a good long action sequence, describing the several days of the hunt through the desert, the various weapons and traps and stratagems employed by the hunter and hunted. In the end Kreega not only defeats Riordan but captures the Earthman's space ship, and we readers are led to believe that, like the Martians in Chad Oliver's 1952 "Final Exam," Kreega and his fellows are going to be able to copy the ship and weapons and build a military force with which to challenge Earth hegemony. (More on this Anderson-Oliver connection below.) Riordan himself is put into suspended animation, still conscious, so that he will be forced to lie inert for centuries, contemplating his defeat.

We see a lot of these stories in which cloddish Earthmen with their high technology are contrasted with aliens who are sensitive and/or artistic and/or live as one with the natural world; I guess all these stories are reflective of a sympathy for the peoples the world over whom Europeans conquered or otherwise dominated, as well as a fear of technology and concern about the environment. For me, this noble savage stuff has worn thin, but the meat of this tale is the well-written chase, and I can strongly recommend "Duel on Syrtis" as an engaging adventure story, a quite successful entertainment.

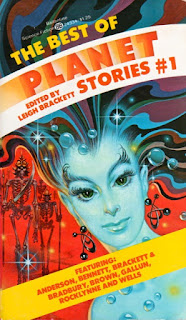

"Duel on Syrtis" has reappeared in Anderson collections and a few anthologies, including 1975's The Best Of Planet Stories, edited by Leigh Brackett. I will also note that, in the issue of Planet Stories that includes "Duel on Syrtis," there is a little one column autobiography by Anderson; among other things, Anderson says that a year spent in Washington, D.C. convinced him that it was not "a town fit to live in" and that his favorite contemporary author is Johannes V. Jensen (Anderson is really into being Scandinavian.)

"The Virgin of Valkarion"

The setting of "The Virgin of Valkarion" reminds one of the Mars of Edgar Rice Burroughs or Leigh Brackett--an old planet, thousands of years ago fertile and ruled by a glorious empire, now a desolate waste of dry sea beds and crumbling ruins. Our hero is Alfric, a claymore-wielding barbarian who rides some kind of hoofed beast and has behind him a long career as bandit and mercenary general. When he arrives at Valkarion, the capital of the last tiny remnant of that empire of long ago, two slaves marked in such a way that it is clear they are property of the priesthood try to ambush and murder him. Why have they targeted him, a total stranger to the environs of Valkarion?

Alfric gets a room in a disreputable inn. The room comes with what we now are calling a "sex worker," and what the introductory blurb of this story calls "a tavern bawd." But this is no ordinary prostitute--she is one of the most beautiful women Alfric has ever seen, and she turns out to be exceptionally skilled in "the arts of love." As that intro blurb told us (that intro is full of spoilers), she is also a Queen--the Empress of Valkarion!

Why are these strange things happening to Alfric? Well, it all has to do with a prophecy and a major political crisis. Not only is tonight important astrologically, but the Emperor is dying, and he has no heir. The priesthood would like to take over the kingdom, but a prophecy from thousands of years ago (recorded in the "Book of the Sibyl") predicts that under just such circumstances an outsider will crown himself Emperor. So the priests have been looking for a guy like Alfric (to murder) and the Empress likewise has been looking for a guy answering Alfric's description (to ally with.) After their sex session, the Empress explains all this to Alfric, who is not unwilling to make himself Emperor, and then they get caught up in the open fighting between the agents of the Temple and those devoted to the Empress. (If the traditionally anti-religious readers of SF haven't already gotten the message, Anderson makes clear that the Empress would be a better ruler than the priests by pointing out that her financial policy features lower tax rates than that of previous administrations, and that the Temple tries to maintain a monopoly on knowledge of the high technology of the Empire's heyday, even executing those who read the old books and try to build the machinery described therein.)

Alfric and the Empress get captured, and the High Priest gives the Empress the opportunity to marry him, which would make him Emperor--if she refuses she will be gang raped by the Temple slaves and then burned at the stake. She agrees, but, once untied, contrives to free Alfric, who kills the high priest. The lovers escape the Temple, and lead the Imperial loyalists against the priests and their dupes, Anderson gives us several (too many) pages of tedious battle scenes. The Empress herself wears armor and rides a beast and stabs people--I think we can say this story includes the much-sought-after "strong female protagonist." The Temple and the Imperial Palace both get burned down in the fracas, but we readers are assured that Alfric and his lover will build a glorious new Empire and found a noble new dynasty.

This story is just OK. I am tired of prophecy stories and the action scenes in this one are not particularly stirring and the characters are not very interesting. "The Virgin of Valkarion" doesn't seem to have set the world on fire--I don't think it ever appeared in an Anderson collection. It was translated into Portuguese, however, for inclusion in a 1965 anthology alongside pieces by H. G. Wells, Arthur C. Clarke, and other worthies.

The issue of Planet Stories that includes "The Virgin of Valkarion" also includes a letter from Chad Oliver, the anthropologist and SF writer whose "Final Exam" I just compared to Anderson's "Duel on Syrtis." In the letter Oliver praises the active SF community of letter-writers, makes literary puns, and says that Anderson's "Duel on Syrtis" was "outstanding." Maybe he really did lift the central idea of "Final Exam" from Anderson! Oliver also, bizarrely, denounces the cover of the March '51 issue, a cover whose use of color I find striking and whose central figure I find mesmerizing. Chad may have been a good anthropologist, but he was no art critic!

**********

Three worthwhile stories by Anderson, even if "The Virgin of Valkarion" is borderline, and I certainly enjoyed rereading van Vogt's "The Star Saint," while the Anderson autobiography and the letter from Chad Oliver both provide fun insights for us classic SF fans. Those old magazines available at the internet archive are full of gems!