The issue of

Planet Stories that features "Outpost on Io" also includes a one-column autobiographical sketch by Brackett. The creator of

Eric John Stark and author of

Sword of Rhiannon tells us she loves the beach and loves to swim, and hopes to travel the world when the war is over. She also loves to act, and, of course, to read and write. This is a very "up" girl, a fun person with a positive attitude who loves everything! But then at the very end of the column comes the dig that will furrow the brow of many dedicated SF readers. After telling us that she thinks SF deserves serious consideration as an art form (hear hear), Leigh Brackett says she believes SF should be "entertainment," not "propaganda," and that most authors with "Messages" give her a "large galloping pain." Take that,

Futurians!*

*It is fun to take a swipe at the bolshie Futurians, but of course pro-technology and pro-market libertarian SF figures like John W. Campbell, Jr. and Robert Heinlein and Poul Anderson were just as dedicated as the commies to using SF to push an agenda and influence people's thinking and change the world. Even Edmond Hamilton used SF to put forward anti-imperialism and anti-big government messages in stories like 1932's "Conquest of Two Worlds" and 1933's "Island of Unreason," and we have to question how serious Brackett's anti-message commitment was when we realize she, as editor, included those two stories in The Best of Edmond Hamilton.

The Solar System is at war, the peoples of Venus, Earth and Mars against the people of Jupiter and her moons. And the war isn't going too well for us! The Jovians have a super weapon that interacts with the atomic structure of metal and makes it explode, which gives them an advantage, a perhaps insuperable one, over the Inner Planet nations because we short-sightedly built all our space ships out of metal!

We learn all this bad news from the dialogue between one Christopher Rory MacVickers, whose "gaunt Celtic head had a grim beauty" and the other characters right after an opening scene in which space captain MacVickers is tossed into a prison/slave labor camp on Io full of Inner Planet war prisoners. These poor bastards explain to MacVickers that he will soon be joining them in working machines that process a weird blue mud practically unique to Io; this strange mud emits a radiation that slowly kills those without protection by gradually turning them to crystal! This horrifying process takes about three months, and among the prisoners are guys who are approaching that limit and are already covered in a sheathe of what looks like blue glass and is almost unbreakable. And there's more news about this mud: the prisoners suspect that the factory they are slaving away in is extracting from the radioactive gunk the very element that powers the enemy superweapon!

Brackett really works overtime developing the atmosphere of misery and dread experienced by the prisoners in the factory, telling us all about the temperature, the humidity, and the smells, all about the looks of hopelessness on their faces and the postures of despair assumed by their naked bodies; and then there are the guards, tentacled Europans, who torture them with electricity from behind radiation shielding.

There is a whole homoerotic subtext to this nightmare vision of a mechanical alien hell. The biggest and toughest prisoner, Birek the Venusian, who has been held in the factory a long time, is mentally unbalanced, and forces the others to bow down and grovel to him. MacVickers resists, but finds that fighting the huge Birek is useless, as the man's crystallized skin feels no pain and punching him only breaks the skin of MacVicker's own fists, drawing blood. When the Europans electrify the room the prisoners are in to torture them, Birkin lays down on top of the fallen MacVickers to absorb some of the electricity coursing through our hero and thus spare MacVickers some pain. Why?

Birek smiled. "The current doesn't hurt much anymore. And I want you for myself--to break."

As for the plot, MacVickers figures out some engineering stuff that gives him a chance to kill the Europans. Then he convinces the other prisoners to help him blow up Io, sacrificing themselves but depriving the Jovians of their superweapon and, presumably, winning the war for the Inner Planets as well as rendering all our maps of the Jovian moons obsolete.

Dark and brutal, a short and successful thriller. "Outpost on Io" has never been anthologized, but was included in Haffner Press's 2002

Martian Quest: The Early Brackett, a

badly battered library copy of which I bought for 25¢ some years ago.

"Child of the Sun" (1942)

Like "Outpost on Io," "Child of the Sun" starts out with a sort of action/horror scene but we quickly get the background via dialogue. That background is that thirty years ago a genius named Gantry Hilton (did Brackett name this dude after

Elmer Gantry?) invented a machine that can not only read your mind, which is bad enough, but can also manipulate its contents--erasing your memories, giving you false memories, changing your personality, etc. People flocked to Gantry for treatment that would make them happy, and the inventor eventually managed to make himself dictator of the Earth, ruler over a society of simple-minded and obedient, but very happy, people, a utopia of conformism where everybody gets along and lives a life bereft of danger or challenge or struggle.

The SF stories I read are always against these kinds of utopias, and "Child of the Sun" is no different. A small number of people, the "Unregenerates," who don't want their brains messed with and prefer a life of risk and individualism are hiding from the Hilton government on various inhospitable asteroids and space hulks and other uncomfortable places beyond Earth. The Unregenerates can't endure in these refuges indefinitely--Brackett, who never shies away from presenting us with dreadful images, conjures up pictures of Unregenerate babies dying of the cold on freezing asteroids.

The leader of the Unregenerates is Eric Falken. As the story begins, Falken and two recent recruits to the Unregenerates, a skinny impoverished young woman called Shelia Moore and an egghead named Paul Avery, are in a spaceship, flying towards Mercury, Hilton's space navy hot on their trail. Somehow, Falken can't shake his pursuers--they seem to always know where he is. Finally, he decides to fly closer to the Sun than any space ship yet has in history, hoping the solar radiation will foil the Hiltonian detection equipment.

Not only do our three characters escape, but they discover a tiny new planet in very close orbit to the Sun! Nobody has ever noticed it before because the sun's radiation is blinding to eyes and instruments at this range. On the planet the three are confronted by surreal and nightmarish phenomena, like a castle that appears and disappears, in which they become lost in a maze of doors.

SF is full of stories about god-like beings who can instantaneously create or destroy things by manipulating matter with their minds and who like to toy with humans. If memory serves, the original Star Trek TV show had many episodes with such beings and the new Star Trek actually had a recurring character who played this sort of role again and again and again. Anyway, on this new little planet Falken, Moore and Avery meet just such a being, a floating ball of flame who says he was born when the Sun and a wandering star had a close encounter in the time before the planets were formed. This creature created all the vanishing castle and all the other crazy phenomena to entertain himself by tormenting our heroes.

The plot of "Child of the Sun" involves Falken trying to trick or persuade the fiery superbeing into creating a hospitable planet for the Unregenerates. It is revealed that Avery is a Hiltonite spy, a mole among the Unregenerates--in fact he is Hilton's son, Miner! Hilton gave Miner psychic powers and Miner, until they got too close to the Sun, had been transmitting their location to the Hiltonite navy, which explains why Falken had such trouble getting away this time. Falken of course considers immediately killing the spy, but Miner has fallen in love with Sheila and come to admire Falken and the Unregenerates' idea of a society of diversity in which people run their own lives. So he renounces his father and with his psychic powers and technical know how he helps Falken and Sheila in their efforts to get a new homeworld for the Unregenerates from the Child of the Sun.

Not bad. In the early 1960s, "Child of the Sun" would reappear in Donald Wollheim's More Adventures on Other Planets and in a Spanish anthology alongside a French novel.

"The Blue Behemoth" (1943)

This is a gritty crime story about rough down-and-out people struggling to make their way in the solar system and corrupt wealthy people trying to make a quick buck; it starts out with a humorous tone but becomes serious and gory.

Our heroes are Bucky Shannon and narrator Jig Bentley, owners and operators of a circus, two fun guys who like to crack jokes, get drunk and get into fist fights. These guys have a creaky old space ship full of freaks (like a scaly Venusian woman who can generate electricity with her body) and monsters (like a Mercurian cave cat) and fly around the system putting on a show. Their crummy circus can only barely break even, and Bucky and Jig are always on the brink of bankruptcy, barely able to pay for the fuel the space ship needs and the food the monsters need, their creditors often at the door demanding payment of bills that are past due.

The first half or so of the plot is a little like a noirish detective thing. The circus's biggest draw is Gertrude the cansin, a beast like a dinosaur with hands from the swamps of Venus. Cansins are what we would call an endangered species--very few have ever been found, and a male cansin has never been seen. One of Shannon and Bentley's many current problems is that Gertrude is sick--according to the monster's handler, Gertrude is in heat but there are no male cansins around, so she is inconsolable and may even die of misery.

A rich guy, Beamish, comes by to hire the circus--he says that, out of charity, he wants to provide entertainment to people in small rural settlements on Venus. There follows the voyage to Venus and then interactions on the swampy second planet from the Sun; this section of the narrative features Beamish and his less than trustworthy partners in crime attempting to (and sometimes succeeding in) double crossing and murdering both fellow criminals and relatively decent people. (Nobody in this milieu of sophisticated criminals, Terran imperialists, Venusian savages, and unsavory businesses that make their bones by exploiting animals is really innocent.) It becomes clear that Beamish and his thuggish partners got wind that some hunter finally discovered a male cansin and want to use Gertrude to find and capture the elusive monster, and they don't want to share the valuable catch with that hunter or with Gertrude's owners, our boys Bucky and Jig.

Things fall apart as the cansins take the initiative. It turns out four female cansins "mate" with a single male cansin, who has a totally different physical form and mental acuity than the female of the species--the male has psychic powers and unites the five monsters via a "community brain." The now unified monster goes on a rampage in a rural Venusian town, even liberating the other monsters on Bucky Shannon and Jig Bentley's ship and enlisting them in their war of revenge on the intelligent bipeds who have been taking advantage of them all these years. Many people are gruesomely killed--Brackett doesn't stint on the gore and violence, nor on descriptions of men sweating, shaking and vomiting in fear. Bucky gets injured and withdrawn from the fight, but Jig organizes several of the circus freaks, all of whom have esoteric powers, and together they drive off the cansins and recapture the other animals, breaking their strike and putting those alien monsters back to work making money for the Man where they belong.

Brackett's non-human intelligent races and monsters are all fun and interesting, and she describes them economically, in a few quick strokes; she gives the reader a sense of complex multicultural societies and weird alien ecosystems without making you wade through too much of fluff. "The Blue Behemoth" is pretty good, but it would not be reprinted until 2007, in Haffner Press's Brackett collection, Lorelei of the Red Mist: Planetary Romances.

"Thralls of the Endless Night" (1943)

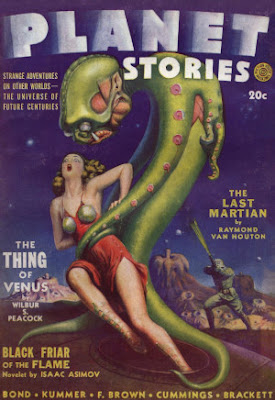

Here's another story that wasn't reprinted until it was included in the 2007 Haffner Press volume. "Thralls of the Endless Night" gets top promotion on the cover of the issue of

Planet Stories in which it appears, along with a striking cover that reflects the undercurrent of rough-and-not-necessarily-consensual sex we see in "Thralls of the Endless Night" as in so many of Brackett's stories.

Another recurring theme of Brackett's body of work we have seen today is class conflict, which is a sort of minor note in "Child of the Sun" and "The Blue Behemoth." But in "Thralls of the Endless Night" class conflict is front and center.

Generations ago, a space ship crashed on this planet. The descendants of the surviving crew have reverted to primitivism, hunting and fighting with spears and living in huts. More interesting to the reader is the fact that they continue to live in the sort of stratified hierarchy which obtained aboard their ancestors' space-going vessel. The people called "Hans" live in the crappiest huts, furthest from the wreck of the space ship, while a small middle class of "Engineers" lives in somewhat bigger huts halfway to the crash site, and then clustered around the ship are the finest huts, those of the officers. Sitting right next to the ship up on the hill is the Captain's hut, the most comfy hut of all. Catching the attention of those of us more interested in sex than class is the fact that the Captain has a sexy "yellow" daughter. "All yellow from head to foot and beautiful pink lids to her eyes." Brackett doesn't come out and say it, but we can tell from such hints that these people are furry that they are mutants!

Wes Kirk is one of the Hans, a man old enough to join the battle line when the "piruts" attack but not old enough yet to accompany the hunters. He hates the Engineers and Officers, assuming they have access to better food or heat sources or something in the ship--as in "Child of the Sun," Brackett uses the image of a baby shivering in the cold as a symbol of privation, and all the Hans' babies are cold all the time.

Wes's father is out hunting when a pirut attack occurs, and papa Kirk is killed--according to Wes, the Officers are to blame for his father's tragic death. Wes's best friend dies in the same attack. These disasters radicalize Wes and he begins airing his revolutionary theories, and so is tortured by being subjected for a defined period to the non-lethal but painful attentions of a blood-sucking carnivorous plant! The yellow-maned daughter of the Captain, she of the "small sharp breasts," thinks Wes doesn't deserved to be punished so severely, and sneaks into the torture hut and liberates him. Instead of being grateful, Wes the angry young man starts delivering one of his diatribes against the Officers, angering the girl; and Brackett cuts right to some titillating but troubling truths about sex and politics that maybe we don't always want to admit:

She was angry now, and perhaps a little scared. He enjoyed making her angry and scared. He enjoyed the thick hot feeling of power it gave him.

Wes kidnaps the yellow girl, a process which entails hitting her repeatedly then lugging her around, pressing her body to his in a way that thrills him. But she doesn't go quietly, cutting him with her knife at one point and hitting him with a rock at another. She also tells him the sort of stuff anti-revolutionaries always say about the Caesars, Robespierres, Lenins and Maos of the world: "You don't care how many people you hurt, do you, as long as you can be a big man...." Good one, yellow girl!

(I'll note here that Brackett never gives the Captain's daughter a name, which may be an oversight or perhaps some kind of comment on gender and class politics among these mutants.)

Wes takes the young lady out into the wilderness where they have to work together in a fight for their lives against monsters. They get captured by piruts who find the yellow girl as sexy as Wes does and threaten to rape her (using euphemisms.) Brackett really pushes the eroticized violence in "Thralls of the Endless Night"--the pirut leader pulls the yellow girl's hair, smacks her, etc. Wes is surprised by all the ways the the piruts are like the Hans--their cave is full of shivering babies just like the Han huts, and they think the Officers near the ship are living an easy life, just like Wes does.

Wes makes common cause with the piruts, and leads them up a poorly guarded secret path and they easily take the Ship by storm. But in the ship they don't find any treasure, and there is no evidence the Officers have been leading an easy life with more heat or more food. The Officers have been keeping others away from the ship because their ancestors, generation after generation, have been passing down a fragmentary legend of ancient times that emphatically states that it is the duty of Officers to make sure nobody under any circumstances opens a particular barred door. When the piruts are told this, they rush to bust open the barred door.

Inside the forbidden compartment is a bunch of documents the illiterate mutants cannot read, but which Brackett lets us readers glimpse--this glimpse reveals to us a terrible tragedy! Centuries ago during a period of interplanetary crisis the Earth tried to make an alliance with the Union of Jovian moons--one of the documents is the treaty that would have sealed the alliance if it had made it to the orbit of Jupiter. Other documents indicate that the failure of the treaty to be signed very likely lead to a devastating war, to the benefit of the aggressive Martian-Venusian Alliance, who had hired pirates to intercept the ship transporting the treaty. The ensuing battle lead to both the treaty-bearing ship and the pirate ship crashing on this asteroid or moon or whatever it is, where the piruts and their descendants kept attacking the treaty ship and its crews' descendants, even though nobody quite remembered why.

Also in the long-sealed compartment is a box of explosive. I figured that the piruts would detonate the explosive and kill everybody, demonstrating to us the futility of class conflict and revolution and giving us a double whammy of tragedy. But Brackett cops out. The piruts set off the explosive alright, but instead of exterminating all these muties the blast opens a crack in the ground that allows more radiation to come up from the planet core, changing the climate for the better so babies won't be cold anymore and agriculture can be more productive--now life will be easier for everybody! There is no more reason for class distinctions or inter-mutant conflict, and the Captain's daughter even surrenders to Wes's rough caresses and we are led to believe they are going to live happily ever after as a loving couple!

I found this deus ex machina happy ending to be pretty disappointing--I wonder if some editor forced a happy ending on Brackett, or she was working on a more palatable happy ending in which the Officers, Hans and piruts did the hard work of resolving their differences but she came up on a deadline and had to go with the gimmicky resolution. The first ninety-something percent of "Thralls of the Endless Night," with its cool premise, class politics, sex and violence and monsters, though, is pretty good.

**********

All four of these stories are entertaining and have some noteworthy idiosyncratic angle or element; I can recommend them to all fans of pre-1950 space opera and planetary romance, especially fans of hard-bitten adventure stories in which there are no real heroes and we are reminded that our societies are corrupt and we are all fallen creatures.