August Derleth is a controversial figure in Lovecraftian circles. On the one hand, he was an enthusiastic supporter of Lovecraft's, playing a critical role in founding Arkham House, which did so much to keep Lovcraft's work accessible after his death, and so is worthy of the gratitude of all devotees of Yog-Sothery. On the other hand, his own writings in the Cthulhu Mythos and his "posthumous collaborations" with Lovecraft have raised some people's ire; in particular, people seem to think that Derleth's own Christian faith, apparently reflected in his writings, conflicts with the genuine spirit of Lovecraft's work, which is materialist and devoid of hope. Even though I think of myself as a Lovecraft fan, and have read Mythos fiction by many of Lovecraft's other colleagues, like the aforementioned Long, Robert Howard, Henry Kuttner, and Robert Bloch, I've never actually read anything by Derleth. Well, today that changes! Now, the stories in Mr. George and Other Odd Persons aren't actually set in the Cthulhu Mythos, but I think they will give me an idea of what Derleth's writing is all about, and in the cover blurb the New York Times says they "rank among Derleth's best tales of the supernatural," and I can't recall the New York Times ever getting anything wrong, can you?

In an introduction Derleth tells us a little about the stories included in Mr. George and Other Odd Persons, which was first put out as a hardcover by Arkham House in 1963 (my copy, part of the "Belmont Future Series," L 92-594, is from 1964.) He claims he wrote each in a single sitting while distracted by students and never had time to revise them...Augie, baby, are you trying to encourage me or discourage me from reading them? Well, let's put our faith in the infallible geniuses at the New York Times and read four stories I selected based on an irrational and esoteric attraction to their titles, stories that appeared in Weird Tales under the pen name Stephen Grendon not long after the end of the Second World War.

"Mr. George" (1947)

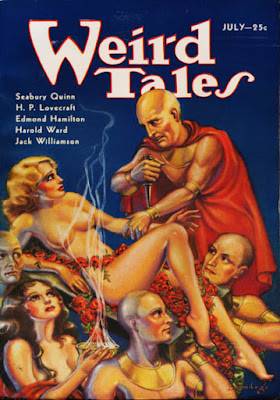

|

| Somebody at Weird Tales pulled a boner and put Derleth's real name on the cover |

Priscilla is a five-year-old orphan, her mother and then her guardian, George Newell, I guess her mother's friend or perhaps boyfriend, having died recently. Priscilla is in the care of three of her mother's cousins, the Lecketts, three jerk offs who find Priscilla a nuisance and covet Priscilla's inheritance of three hundred thousand dollars. If Priscilla dies, they get the money, and it is not long before they are plotting the little girl's untimely demise.

Priscilla misses "Mr. George," as she calls Newell, and does things like writing him notes asking him to come back and riding the streetcar alone to the cemetery to put them on his grave. She begins hearing Newell's voice, and, sure enough, he begins manifesting himself in the Leckett household. As the three Lecketts one by one set death traps for Priscilla, Newell's ghost warns Priscilla away from them and tricks each creepo in turn into getting killed by his or her own trap. Then the ghost bids Priscilla a final farewell and she moves to the home of a nice lady friend of Newell's.

This story is competent, if a little obvious and predictable. Perhaps Derleth's view of money and class is of interest; the "nice lady" has the kind of free and easy attitude towards the filthy lucre that apparently earns Derleth's approval ("She dressed well, having money and knowing how to use it, knowing it was only a means to an end, not an end in itself....[she] was colorful and jeweled as against their [the two female Lecketts'] almost offensive plainness"), while the evil would-be-child-murderers are cheap and grasping. It is strange to see an intellectual type praising a woman for spending money on jewels and condemning women for dressing unostentatiously, but there it is.

The Canadian edition of the issue of Weird Tales that featured "Mr. George" is available at the Internet Archive; this looks like a good issue, with lots of fun illustrations and stories by Ted Sturgeon, Robert Bloch and Eric Frank Russell, as well as a poem by Stanton Coblentz!

|

| Eat your heart out Wilfred Owen! |

I just bought shoes at Banana Republic that have wooden heels, which means everybody in downtown Columbus can hear me coming as I clop clop on the cobblestones.

"Dead Man's Shoes" is more to my taste than "Mr. George." Jack and Howard Sherman joined the same paratrooper unit and served side by side in World War II until Jack was killed. Howard was wounded and sent stateside, where he started making time with Jack's widow and sold his brother's service boots to Doug Lynn. When Lynn wears the boots while out in the countryside collecting mushrooms, he has brief but emotionally powerful flashbacks to the battle in which Jack was killed. He begins to get the idea that it wasn't a "Jap" who killed Jack, but Howard! Stressed out by these horrifying visions, Lynn surreptitiously switches boots with Howard. Howard doesn't realize he is wearing Jack's boots, and one day, while he is in the wilderness near a cliff, his dead brother exacts his revenge!

Shorter, and more unusual than "Mr. George"-- I like this one.

|

| Like a foreshadowing of horrors to come, this 1964 book exhibits a grammatical error which has become alarmingly common in our own decadent digital age |

"The Blue Spectacles" (1949)

I wear glasses--gotta read this one in solidarity with all the other people with poor eyesight out there who are too squeamish to wear contacts.

Through an unlikely series of coincidences, New Orleans divorce lawyer and womanizer Alan Verneul acquires a centuries-old pair of blue Chinese glasses and puts them on during Mardi Gras. These glasses, when worn by an immoral person, give that person a vision of an earlier incarnation of his life(force?) and punish him. This horny lawyer's punishment is not to merely suffer disbarment and the spectacle of his wife screwing up the interview for the job she has been dreaming of her entire life--no, he experiences immersive visions of the New Orleans of 1811, where Jean Lafitte (famous pirate and hero of the 1812 war) lynched his ancestor for raping and seducing various women. When 19th-century Verneul is killed in this vision, the Verneul of the 20th-century also dies.

This one feels a little contrived, from how the lawyer gets the glasses to the "powers" of the glasses. If you are looking for a short story about apparel which metes out vigilante justice, "Dead Man's Shoes" is the superior. "Blue Spectacles" is merely acceptable.

The issue of Weird Tales in which "The Blue Spectacles" first appeared is available to read at the Internet Archive. This issue's illustrations are leaving me cold, but it does include stories by Fredric Brown, Fritz Leiber, Robert Bloch and your new favorite poet, Stanton Coblentz.

"The Extra Passenger" (1947)

I was just telling my brother that riding the subway every day is like a paradise compared to driving every day.

Simon Arodias is a sophisticated Londoner who has long supported himself via crime. He decides the time has come to kill his eccentric Uncle Thaddeus who lives in the country, so that he can inherit Unc's pile of money. Arodias comes up with the scheme of booking a private compartment on a Scotland-bound train, sneaking off at Unc's village en-route and murdering the old bird, then stealing an automobile and driving to the next train station and getting back on the train, into his private compartment. Nobody will know he left the train, and he'll have a perfect alibi.

All goes according to plan until Arodias gets back into his private compartment to discover a man there, sleeping, a hat over his face. This mysterious character, Arodias gradually learns, is the animated corpse of his Uncle Thaddeus--Thaddeus was a wizard, and was able to ensure that his own corpse could achieve vengeance on his killer (one of Thaddeus' familiars flew the corpse to the train.)

This story isn't bad; about as good, I reckon, as "Dead Man's Shoes."

The issue of Weird Tales with "The Extra Passenger" is another one you can read for free at the Internet Archive, and it is populated by SF giants: Edmond Hamilton, Theodore Sturgeon, and Ray Bradbury, plus two poems by H. P. Lovecraft. One of the Lovecraft poems, and its accompanying illustration, appear to describe exactly the kind of familiar mentioned in "The Extra Passenger."

**********

Looked at as a body, what is noteworthy about these stories is how each is structured as a kind of morality play or tale of crime and condign punishment: in each, somebody plots a reprehensible sin and then some supernatural force kills him, achieving a sort of rough justice. These stories all depict a moral universe in which transgressions against other people and the social order are punished via supernatural means; perhaps surprisingly (given the back cover text about "unholy creatures which cross dimensions to destroy") the supernatural element in each of these four stories is not a radical menace, but an agent of conservatism that defends the weak and preserves the social order--the real villain in each story is a mortal human driven by lust or greed, somebody who covets his neighbor's property or wife. Obviously this is a contrast to typical Lovecraftian horror, which is full of collapsing societies and degenerating races, individuals who go insane, and alien forces which overturn all established orders, even the conventional laws of physics; Lovecraftian horror gets its "kick" from reminding us that the universe is in a state of amoral chaos, while these Derleth stories assure us that the universe is just, though it may work in mysterious ways.

Even if Derleth really did just dash these four stories off while University of Wisconsin co-eds were badgering him for help on their exams, and never bothered to revise them, none is so shoddily put together that it isn't an acceptable entertainment, though "The Blue Spectacles" is kind of teetering on the brink. None of them feels particularly distinctive or memorable, either; they feel kind of like filler. I have to admit that the fact that each features a supernatural element which works for justice and each ends with the evildoer punished weakens them as horror stories in my eyes....they feel like a domesticated breed of horror story. Like detective stories (wikipedia is telling me Derleth wrote over 70 detective stories) in which the cops always get their man, the four Derleth stories we discussed today, while nominally "horror" stories, depict the orderly and just world we wished we lived in rather than the arbitrary and miserable world we fear we live in, and are more comforting than disturbing. I prefer my horror stories to be suspenseful, surprising and unsettling, and so I don't think I'll be reading any more Derleth stories any time soon.

**********

Check out the way Belmont's crack marketing staff appealed to 1964's science fiction community (this page appears opposite the title page of my copy of Mr. George and Other Odd Persons.) Everybody loves center aligned text, amirite?