Let's read about sex! (

Everybody's doing it!)

A few months ago, at an antique mall in, I think, Brunswick, MD, I picked up for a dollar a copy of Shudder Again, an anthology of "22 Tales of Sex and Horror" praised by the "Democracy Dies in Darkness" broadsheet as "chilling and imaginative" and by Publisher's Weekly as "freewheeling." Shudder Again, published first in hardcover in 1993, is editor Michele Slung's sequel to her successful 1991 anthology I Shudder at Your Touch and has a pretty mesmerizing and somewhat disturbing cover illustration by Mel Odom. Are those oversized black monster hands clutching that pale sleepy-looking woman's breasts, or just a wacky piece of couture designed to look like oversized black monster hands? I'm finding it hard to look away.

(Check out the original painting from which this image is adapted, The Chartreuse Bow, at Odom's website. The woman in her original form is not quite so pale and wears a crown, so seems less vulnerable.)

Slung has had a successful career as an anthologist putting together things aimed at the women's market, like collections of folk wisdom uttered by mothers and anthologies of genre fiction (detective stuff, erotica) by women and memoirs of women explorers and adventurers. Slung is very opinionated, and the author's bios at the end of Shudder Again include all kinds of odd asides and idiosyncratic criticisms, which is an interesting editorial choice; usually these author's bios are cold, like encyclopedia entries, or single-mindedly rave about the authors because the editor wants to sell the book and to keep on the good side of all the authors and their reps. I like Slung's outspokenness, but I question it is a career strategy.

Lest you think I bought this thing only because I was hypnotized by the cover, I inform you that quite a few of the stories in Shudder Again are by people in whose work we here at MPorcius Fiction Log are interested. Today we'll read four of these tales of sex and horror; a day may come when we read four more of them--who can say? I will note that I am skipping Thomas Ligotti's "Eye of the Lynx" because it is a component of a sequence of stories which I will someday read all in one fell swoop, and that I have already read and blogged about Charles Beaumont's 1955 "The Crooked Man," a switcheroo story about a totalitarian society in which heterosexuality is prohibited, and Robert Bloch's 1975 "The Model," which I bitterly denounced as "lackluster," "anemic," and "feeble."

"Heavy Set" by Ray Bradbury (1964)

This tale first appeared in

Playboy, our most prestigious skin rag, and Ray's name was right on the top of the cover, higher than Cassius Clay's. I guess you could call it a character study. On the California coast, a thirty-year-old guy who works out all the time still lives with his mother. He has an adult job, working on the powerlines, but in some ways he acts like a kid, which Bradbury dramatizes by having him dress up as a little kid on Halloween. Women chase him, I guess because of his Herculean physique ("Hercules" is one of his nicknames, along with "Heavy Set," "Samson," and "Sammy"), but he seems to have no interest in them. The sad second half of the story and its creepy climax suggest Sammy's obsessive weight-lifting and strength training are the result of his sublimating his sexual desire for his mother, and that his mother's emotional neediness is the root cause of his Oedipal complex and arrested development.

A solid, essentially mainstream (non-SF) piece of work by Bradbury. He doesn't push that Freudian stuff, doesn't use the terms "sublimated" or "arrested development" or "Oedipal complex;" that is my interpretation, and it is possible he would reject all of it--this is a story about human unhappiness that shows rather than tells and is open to reader interpretation, not some lame psychology lecture. Worth your time.

"Heavy Set" would be included in the collection I Sing the Body Electric and some later Bradbury collections as well as several anthologies, including one presumably published to capitalize on the success of that David Lynch movie that makes my wife cry and another celebrating post-Christian America's favorite holiday.

"The Face of Helene Bournouw" by Harlan Ellison (1960)

Apparently, this story was first published in a magazine called

Collage. While hunting, in vain, for any references online to

Collage that were not about "The Face of Helene Bournouw," I learned that this story was the basis for a 1998 TV presentation. After appearing in a magazine that is lost to history, and before being immortalized on the boob tube, "The Face of Helene Bournouw" was collected in

Love Ain't Nothing But Sex Misspelled in 1968 and then, in 1975, in the oft-reprinted

Deathbird Stories.

After the understated, down-to-earth prose and believable true-to-life characters in Bradbury's "Heavy Set," Ellison's turn-everything-up-to-eleven style ("In the perfect minds of Gods too perfect even to have been conjured by mortals, there never existed a love as drenched in empathy as the love between Helene Bournouw and the man she accepted gratefully"), his try-hard "literary" slosh ("These are the sounds in the night: First, the sound of darkness, lapping at the edges of a sea of movement, itself called silence...second, the fingertip-sensed sound of the cyclical movement of the universe as it gnaws its way through the dust-film called Time...last, the animal sounds of two people making love") and his bewildering metaphors ("there was never a passion such as this: straight as steel ties to an indecipherable horizon") made me groan at how much time they wasted and how little information they conveyed, and then laugh at their ridiculousness. Maybe these lines, from the first page of the story, are supposed to be bad? Like, as a joke? They certainly fail to conjure images, set a mood, make a point, or add to the plot.

Anyway, this chick Helene Bournouw is an advertising model and the hottest babe in New York City. Even hotter, we are told, than Suzy Parker or Elizabeth Taylor, who, as google image search will tell you, were pretty damn hot in 1960 when this story appeared in a magazine nobody ever heard of. We see her dump her boyfriend, the head of a shipping company. He commits suicide and this snarls up the supply chain and damages the US economy. Then she drops in on her other boyfriend, the greatest artist in America, a guy who lives in a loft, subsisting on day-old bread because he has yet to be discovered. She tells him his work sucks and so he abandons art and moves back to the Middle West. Then Bournouw visits the priest she has seduced and after they have sex he writes a theological treatise that "would serve to sever the jugular of the Judeo-Christian ethic." We also learn that she has left some commie diplomat with blue balls so that when he attends a UN conference he will refuse to make any accommodations.

Finally, we see Bournouw meet nine dwarfish monsters in a shabby old building in the Bowery. I thought she must be a robot employed by aliens to disrupt Earth's economy and society in preparation for an invasion. But no, Ellison's ending is even lamer than that--she is a robot employed by the Devil to cause strife up here on Earth. I guess as a satire of mid-century business practices, one of the demons complains that he prefers "the old ways," but is upbraided by one of his infernal comrades: "In a time of public relations, automation, advertising, the only way we can hope to carry on our work is to use the tools of the era."

The only remotely sexy, horrible, or interesting part of the story is the last line, which indicates that the nine demons are going to gang bang the robot that is Bournouw.

When I finished reading this story I planned to tell you it was "barely acceptable," but rereading those sentences I am quoting or referring to above has led me to realize the story is even worse than I at first believed: the first time I read them, those sentences numbed my mind so I didn't suffer their full impact, the way a drunk is protected in a car crash by his limpness; reading them carefully enough to type them out myself for your benefit, dear reader, has brought home to me how empty and stupid they are.

Another thing. Through most of the story, I thought it was about how women can be evil and use their sexual wiles to destroy men, who when dazzled by sexual desire can foolishly betray their fellows and themselves. I recognize that you aren't supposed to think that way anymore, but at least the story would have been about real life, about real people, about human emotion. The gimmicky reveal that the woman is a droid operated by demons from Hell undercuts any human feeling the story had. Dumb!

Thumbs down!

|

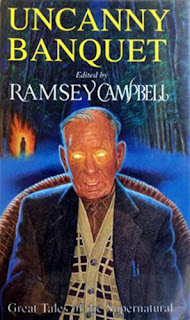

On the right is the cover, by Tom Kidd, of a 2011 expanded edition of Deathbird Stories

published by Subterranean Press |

"A Host of Furious Fancies" by J. G. Ballard (1980)

Oh no, here's

another chance for me to out myself as ineligible for membership in the in crowd by attacking a story by a New Wave icon. Well, maybe this story is a good one...I liked

"Bilennium," after all, and

"The Garden of Time"...Ballard's stories aren't

all gimmicky scams like those famous Kennedycentric squibs...maybe I won't

have to attack this one. At least "A Host of Furious Fancies" first appeared in a magazine I've heard of,

Time Out, though I'll be damned if I can find a cover image of the issue that included this story along with the theatre and cinema listings.

"A Host of Furious Fancies" is a crazy detective story, sort of based on the story of Cinderella, with an unreliable narrator and a twist ending; the story is full of Freudian concepts, and is presumably a satire of Freudianism.

In the opening frame portion of the story, the narrator points out to us readers an unusual married couple in a fancy restaurant in Monte Carlo, a beautiful young woman accompanied by a feeble-minded old man. The narrator is a doctor and the main text of the story is his retailing of the story of how he cured the young woman of an acute case of mental illness.

Basically, she was a teenaged orphan, her mother killed in a plane crash and her father, a wealthy businessman, a suicide. She went bonkers, acting out, for years, the story of Cinderella, cleaning her father's now vacant mansion obsessively, perhaps because her father raped her. The narrator claims to have cured the girl of her insanity by helping her act out the happy ending of the Cinderella story, casting himself as Prince Charming. The narrator's story is full of discordant, hard to believe, paradoxical elements; for example, the narrator is a dermatologist who thinks Christianity and psychoanalysis are scams, but has nice things to say about the nuns he meets and makes extensive use of psychoanalytic ideas in his curing of the young woman.

In the last paragraphs of the story, the closing frame section, it becomes apparent that the narrator is the old man, not a character distinct from the old man, as we were initially permitted to believe. Also, that the narrator is insane, and that his whole story is made up; in fact, he is the beautiful woman's father, not her husband, and she is working with doctors and the nuns of a sanitarium to cure him, not the other way around, as in the story. The main text of "A Host of Furious Fancies" is merely a fantasy that the narrator indulges in that reflects his incestuous lust for his daughter.

On page 21 of his 1976 collection Down Here in the Dream Quarter, Barry Malzberg likens himself to Ballard, and I vaguely recall, in an interview or something, Malzberg expressing something like envy of Ballard, suggesting that Ballard has accomplished what Malzberg has tried, and perhaps failed, to accomplish. (Not that you or I or anybody should trust my memory.) "A Host of Furious Fancies" brought this to mind because it is much like a Malzberg story, with its unreliable narrator who is insane, but, unlike Malzberg's typically slapdash productions, Ballard's story here is carefully polished and thoughtfully constructed and draws deeply from multiple sources (Cinderella and Freudianism.)

This story is pretty good. "A Host of Furious Fancies" first was printed in book form in 1982 in the collection Myths of the Near Future, which has appeared in numerous editions in several languages.

"Ravissante" by Robert Aickman (1968)

In the fall of 2019 I read World Fantasy Award winner

Robert Aickman's story "Compulsory Games" and said that I would "definitely be exploring more" of Aickman's work in the future and then promptly forgot all about my pledge and even Aickman's very existence. As my wife would tell you, it is not unusual for me to say I am going to do something and then totally forget all about it, and even for me to do something and then totally forget I did it. A couple of months ago Abe Greenwald on the Commentary

Magazine Podcast recommended Aickman's work, so, when I saw Aickman's name on the contents page of Shudder Again while I was mapping out what to read for this blog post, it rang a bell, and I decided to give this guy whom I had thought I had never read a try; I only just now, when typing "Aickman" into the "Labels" field and seeing it be autocompleted, realized this will be my second Aickman story, not my first.

"Ravissante" is like three times as long as the other stories I've been talking about today. It begins with a longish frame story, in which our narrator, meets and has a brief acquaintance with an odd married couple, a painter who gave up painting to become an art book editor and his quiet wife. Harlan Ellison's reference to Suzy Parker perhaps sent you to google image search to feast your eyes, and it would similarly be just that Aickman's comparison of his character's canvases to the late work of Charles Sims inspire you to investigate Sims, a painter about whom I had never heard, or had forgotten about.

The narrator's relationship with the couple was not very intimate, and years after having seen them for the last time, the narrator receives word that the painter has died and he has been appointed one of the executors of his will. The quiet wife does not seem very upset, and in fact is determined to burn her husband's many canvases, and his papers. The narrator keeps one of the scores of paintings for himself, as well as a suitcase of documents. Inside the suitcase, along with the heavily marked up drafts of the texts of those art books, is a sort of memoir of a strange event in the painter's life; this document takes up like two-thirds of the text of "Ravissante."

The unnamed painter, writing at the age of twenty-six, tells us he is not very interested in women and sex; he would only want to have a relationship with a truly beautiful woman, and doubts he has the capacity to attract such a beauty, and refuses to settle. Also, he fears a woman would restrict his freedom, take over his life, stifle him the way his mother dominated his father. (Woah, these are some of our favorite themes here at MPorcius Fiction Log!)

A devotee of the Symbolist School, the painter went to Belgian to see the works of some of his favorite artists, like Fernand Khnopff and Felicien Rops, with whom I was familiar, and a bunch of guys I'd never heard of, like Antoine Wiertz, a guy who painted suicides, decapitated heads, atrocities, and a portrait of Bonaparte burning in Hell, where he is upbraided by his victims. Nice! The memoirist has an appointment to meet the ancient widow of one of his favorite artists, who is also unnamed. This is a squat "almost gnomelike" creature with a voice like a "croak."

Most of the memoir describes the painter's bizarre and surreal interview with the widow, during which various unlikely and even impossible things happen. The ugly old woman throws the painter off balance in a multitude of ways, flirting with him, for example, and offering dismissive and insulting assessments of the painter's artistic heroes, men she knew and about whom she shares unwelcome truths. He would like to look at her collection of paintings, but she has managed things so that it is too dark for him to get a good look at them; she reveals that she owns a vast collection of rare prewar art journals, periodicals full of information and inspiration that would likely be very valuable to the painter, but offers him no opportunity to look at them.

Things grow progressively more weird. The painter catches glimpses of strange animals--one might be a black poodle, or perhaps it is a monstrous spider the size of a poodle. The domineering woman begins bragging that her adopted daughter, who is away on some trip, is the most beautiful woman in Europe, that if the painter could see her naked it would be a revelation to him. She orders her visitor to come to the adoptive daughter's room to admire the beauty's clothes--soon she is commanding him to caress and kiss the clothes, and he complies, and finds the smell of the absent woman intoxicating. The climax of the story, the most impossible thing, is that hanging in the adoptive daughter's room is a painting that must be by the painter himself, but one he does not remember painting, one that evidences a change in his customary tone and subject matter. The widow dismissively denounces the painting, as she has all the paintings she has spoken of, and then, as the painter makes to leave, whips out some scissors, and requests a souvenir, apparently a lock of his hair. The painter flees, escaping without surrendering any of his hair.

"Ravissante" is very well-written--all that stuff I sometimes talk about like stye and pacing and narrative structure are flawless. The story is full of vivid images and weird events and Aickman develops moods effectively. And of course I like that it is about domineering women and men's fear of sexual relationships, and that it draws so much upon, and actually taught me something about, Art Nouveau and Symbolism, art movements I find exciting. (I still need a lot of education; I didn't develop any interest in the fine arts until I was in college, because the painters my parents talked about, like Grandma Moses and Norman Rockwell, and the painters my public school teachers talked about, like Monet, Picasso and Van Gogh, are so god-damned lame.)

At the same time I really enjoyed "Ravissante" and of course am recommending it, I can see how it might be seen as frustrating because Aickman doesn't tie up the loose ends or tell us what is really going on. Is there any connection between the two widows in the story, both of whom are dismissive of their husbands' paintings? Could they be the same woman somehow, a time traveler or a vampire or a witch or something? And how could one of the painter's works, apparently a product of a later, more cynical and bitter period in his life, have gotten into that room in Belgium? (Another time travel clue.) Aickman's story, in part, is about how life is full of inexplicable things, a point both the narrator of the frame story and the painter make explicitly,* and so mirrors life by leaving lots of stuff unexplained.

*E. g., "Human relationships are so fantastically oblique that one can never be sure" and "I have learned that what one remembers is always far from what took place." "Ravissante" apparently first appeared in the collection

Sub Rosa, and has since appeared in several anthologies and collections.

The Bradbury is good, as we sort of expect, and the Ballard and Aickman are better than I expected, good enough that they have me thinking I should really take the time to read more of their stories, though whether I will make good on this resolution remains to be seen. As for the Ellison...well, like Barry Malzberg, who I also sort of slagged today, our pal Harlan wrote for money and produced a huge volume of work, at high speed, in which there are bound to be some clunkers; I won't hold it against him.

Next time, at MPorcius Fiction Log: we read a 1964 SF novel by a major British author.