|

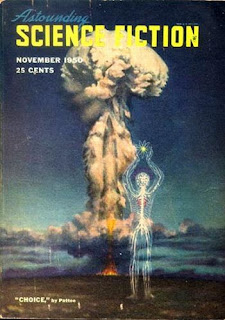

| Not my copy |

|

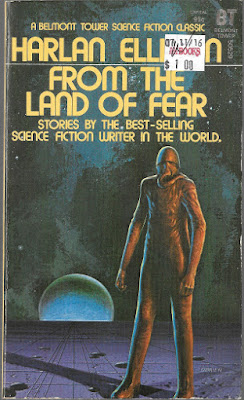

| My copy |

"Agent of Vega" (1949)

The one that started it all! "Agent of Vega" first appeared in Astounding and seven years later was included by Andre Norton in her anthology Space Police.

It is the far future and the human-led Vegan Confederacy is trying to manage "eighteen thousand individual civilizations" spread across the galaxy. The Department of Galactic Zones is the Vegan Confederacy's secret police force, and one of its top operatives is Zone Agent Iliff. Iliff is sent to planet Gull to help one of Vega's few non-human agents, a new recruit by the name of Pagadan, a member of the race of telepaths known as the Lannai. The Lannai may not be human, but Pagadan looks exactly like a hot chick with a head of hair that resembles "a silver-shimmering fluffy crest of something like feathers." (It looks like Boris actually read the book!)

Pagadan has stumbled upon an operation by noncorporeal parasitic aliens to take over the galaxy! These aliens, the Ceetal, can take over your body and they have already infiltrated the elites of almost one thousand star systems! To stop this conspiracy Iliff and our girl Pag do the stuff you expect people to do in detective stories, like putting on disguises, interrogating people, getting captured, and escaping. It turns out the Ceetal have taken over the body of the galaxy's master criminal, a genius psyker and space pirate whom Iliff has been chasing his entire career! In a blistering final battle involving space armor, ray guns, high tech booby traps and psychic blasts, Iliff and Pagadan defeat the pirate and save the galaxy.

|

| The first page of my copy includes an excerpt from the title story |

On the bad side, I thought Schmitz's style a little difficult to follow, and that the way he constructed the plot sapped much of its potential for suspense and excitement. Instead of following Iliff and/or Pagadan closely so the reader learns the truth of what is going on as the heroes learn it, Schmitz includes lots of scenes from the points of view of the Ceetal and from that of Iliff's supervisors, so that we readers know more than the protagonists. Further distancing us from the action are Schmitz's practices of providing information via a recitation of government reports and having some tense scenes described in dialogue after the fact.

Not bad, but not great.

"The Illusionists" (1951)

According to Wikipedia, "The Illusionists" is a later title for the story "Space Fear," which appeared originally in Astounding. The copyright page of my edition of Agent of Vega implies the stories appearing therein may have been rewritten by Schmitz for book publication; instead of simply listing story titles and original places of publication, readers are alerted that Agent of Vega is "based upon" earlier (unspecified) work that appeared in Astounding and Galaxy. Though the last written of the four, "The Illusionists" appears as the second story in this book.

Padagan, now a full-fledged Zone agent herself, is in the Ulphi system, her heavily-armed and super-fast one-man ship serving as bait for Bjanta space pirates. (The Bjanta are hideous arthropodic people who regularly prey on innocent planets.) While in the Ulphi system Pagadan uncovers a horrible conspiracy on the human-inhabited planet that orbits Ulphi--somebody has achieved the ability to control the minds of millions of Ulphins and made himself secret dictator! In order to keep the Ulphi system isolated he has hypnotized the planet's entire population so that they suffer "space fear," a phobia that makes it impossible for them to leave the planet.

I could voice the same criticisms of "The Illusionists" that I did about the first story; there are plenty of good SF ideas, but the style and structure weaken the story, making it a little hard to follow and draining it of emotion; there are lots of scenes of minor characters yapping and reading government documents, and action sequences which we learn about second hand through dialogue. The most thrilling scenes are those in which the Traditionalist woman uses her anti-grav devices and hand to hand combat skills to escape a mind-controlled mob.

OK.

"The Truth About Cushgar" (1950)

In this story, which first appeared in Astounding, we learn that the Vegan Confederacy isn't the only interstellar political unit in the galaxy; in fact there are several rival organizations with jurisdiction over hundreds or more systems. Cushgar is one such empire, one far more exploitative than Vega. In the first page of the story we learn that the Department of Galactic Zones has managed to subdue Cushgar and install Vegan governors over all the Cushgar planets, all without resorting to war. How? The other departments of the Vegan Confederacy don't even know! But we readers learn!

"The Truth About Cushgar" is the tale of Zone Agent Zamman Tarradang-Pok, a female member of an isolated strain of humanity, the Daya-Bal, that evolved on its own for some centuries into a beautiful elfish race. We learn her story largely through second hand accounts from other characters and from flashbacks. Zamm (as everybody calls her) was a young mother on vacation with her husband and son on a luxury space liner when the liner was captured by space pirates. She was left behind when her husband and son were taken captive by the escaping pirates, who left no clues to their identity or place of origin; Zamm doesn't even know if they were human or alien!

Since that terrible day seventeen years ago Zamm has been hunting the galaxy and her own mind for clues that might lead her to the culprits and her enslaved family members. As an agent of Galactic Zones she zips hither and yon, capturing space pirates and interrogating them. In an eldritch bit of psychological wizardry, she has had lifelike robot replicas of her son and husband made--talking to and caressing these simulacra triggers vivid memories, and as Zamm relives the traumatic attack on the luxury liner a psychology robot taps into her brain, seeking just one vital clue to the identity of the kidnappers! These repeated brain scanning sessions threaten to drive the psychologically scarred Zamm over the edge into total insanity!

|

| Back cover of my copy, which includes an excerpt from "The Truth About Cushgar." |

This is the best story in Agents of Vega so far; Zamm the distaff outer space Captain Ahab is a more interesting character than Pagadan or Iliff, and the scenes of terror and violence in this one are better, much more exciting. (When an insanely envious scientist is holding his more successful brother in shackles, Zamm rescues the good brother by blowing the head off of the evil brother with a pistol; this is the kind of activity we look for in genre literature, isn't it?) The style is also better; the story flows more smoothly and is easier to follow. The somewhat silly ghost ship gimmick kind of comes out of left field and it is a little disappointing that Cushgar turns out to be a paper tiger, but this questionable means of resolving the plot only takes up the last fifth or so of the 38-page story, and of course is in the hard SF tradition of characters using superior knowledge and intelligence to trick their adversaries.

Good.

"The Second Night of Summer" (1950)

|

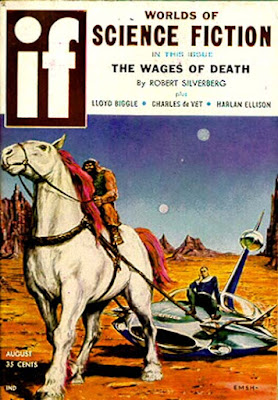

| "Second Night of Summer" was a Galaxy cover story |

The plot of "The Second Night of Summer" reminds me of some kind of Warhammer 40,000 wargame scenario: malevolent extragalactic aliens, the Halpa, are about to teleport onto Noorhut and Grandma has to keep the human inhabitants of the planet ignorant of the threat and ambush the teleporting monsters. If the Halpa start taking over the world the eight Vegan Confederacy battleships orbiting above (unbeknownst to the Noorhuttians) will use their extermination weapons to sterilize the planet. We are informed that the Vegan government has already done this to over one thousand Halpa-infested planets over the last few millenia.

This story feels short and concise; it isn't overburdened with too many minor characters like the other three stories in Agent of Vega. The Halpa are unusual, interesting aliens, and the details of the war between the Vegans and Halpa are also well thought out. Though it lacks the compelling emotional content of "The Truth About Cushgar," it vies with that story for title of best in the collection.

I like it!

**********

The four stories in Agent of Vega are entertaining specimens of traditional SF in which elites who callously manipulate the hoi polloi fight space pirates and hostile aliens with starships, ray guns and psychic powers. Schmitz is good at presenting all the SF gadgetry and concepts we love. Maybe 21st century readers will find Agent of Vega attractive because it is women who are manipulating the commoners, crossing the galaxy in search of revenge, hanging out with robots, and mowing people down with energy weapons. These four tales are a worthwhile read for classic SF fans and people who want to investigate the conventional assertion that SF from the past is irredeemably sexist.

**********

The last page of my edition of Agent of Vega, Permabook M 4242, is an ad for a book, but not a science fiction book. It's an ad for Hillel Black's Buy Now, Pay Later, a warning about the dangers of consumer debt! For a quote from Buy Now, Pay Later check out libertarian luminary Virginia Postrel's November 2008 column in The Atlantic about consumer credit; spoiler alert--Postrel doesn't think consumer debt is anything to get too excited about.