Hal said slowly, "An anarchist society, Mike, has a problem in basic survival. The original anarchists believed that anarchism would naturally have a socialist framework in which everybody joined together in professional or trade unions and that way helped keep things going by agreement. But when anarchism finally came it was a product of extreme rightist individualists and the technologists. The Techs worked out the Kirlian thing, and the rightists set it up so that each person could do as he pleased-- except no forcing anybody to do anything."

I had such a great time with Quest for the Future in our last installment of MPorcius Fiction Log that I feel another Van Vogt marathon coming on! (We had a Van Vogt marathon back in early 2015, you'll remember, perhaps with a song in your heart, perhaps with a scowl on your face.) Today we have 1977's The Anarchistic Colossus, published by Ace, with a great cover by Bart Forbes. (Van Vogt's Future Glitter also had a Forbes cover I admired.) I love the penciled look of those two little images on the sides, the sad eyes, and the powerful lighting effects. Very good!

As he describes in the intro, in The Anarchistic Colossus Van Vogt tries to envision an anarchist society (one without government or police), taking into consideration the fact (according to Van Vogt, at least, who spent time studying and thinking about psychology) that men are violent jerks always ready to abuse and exploit others. (Quest for the Future, you'll remember, also was, in part, about trying to create a peaceful society and having to resolve the fact that so many people are "paranoid" and exploit others.) Van Vogt's formula for workable anarchism involves computers and Kirlian photography.

You probably know what a computer is, but in case you don't know what Kirlian photography is, wikipedia informs us that it is photography that records the "phenomenon of electrical coronal discharges" around objects. Believers in the paranormal, starting with Soviet electrical engineer Semyon Kirlian and his wife Valentina in the World War II era, thought the color (or whatever) of your "Kirlian aura" indicated your emotional state. So in Van Vogt's book, on every street corner are pillars or posts equipped with Kirlian cameras and energy projector guns, filled with computers and all connected to a massive central computer. The pillars (the novel's characters just call them "Kirlians") observe your behavior and read your aura to see if you are in a violent or duplicitous or other antisocial mood, and zap you unconscious if you misbehave.

If you are saying, "That's not anarchism, that's just letting a computer be the government and the police," I'm inclined to agree.

I associate anarchism with libertarian types like David Friedman, son of Milton Friedman, who was, like me, an alumnus of Rutgers University. (For some reason, when I was at Rutgers nobody ever talked up Milton Friedman, who won the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, and championed human freedom. We did hear a lot about Rutgers alum Paul Robeson, who threw a ball, sang a song, and championed Josef Stalin.) But the anarchism of the year 2102 in this book, in some ways at least, is less libertarian than our own pre-Trump era / pre-Rodham-Clinton era America of 2016:

"People who won't flush toilets, who pinch or slap, open other people's mail, violate another's privacy, never bathe, cheat at cards, make fun of someone else's religion, and...people who spread misleading, or lying, or intent-to-harm-or-deceive gossip. I could get a dose of unconsciousness from ten minutes to several hours for any one of those."This doesn't sound like a society which puts much value on freedom of speech--the anarchistic society Van Vogt cooked up for this book is not passing the purity test! Still, there are no taxes, no welfare state, and no government regulations, so I guess it is a society on the spectrum of capitalist or right-wing anarchism. Maybe the "extreme rightists" who "originally forced anarchism upon the world" had to compromise with the socialist anarchists, who are represented in the novel (though they seem ineffectual and I suspected Van Vogt was poking fun at them.)

|

| I must report there are no horses in this book. |

David Friedman, at this webpage, admits that the "hardest problem" in making an anarcho-capitalist society work would be defense against a powerful external foe. (In the 1970s when he addressed the issue he doubted an anarchist USA could contain the Soviet Union because few people would be willling to pay for a powerful defense establishment.) Van Vogt's plot directly addresses this issue; The Anarchistic Colossus depicts an anarchist Earth at war with an aristocratic society of space aliens, the four-legged Ig of planet Slua. In fact, we readers learn about Earth society alongside an Ig spy, a Baron who resides on Slua and casts his consciousness across the black vastness of space to piggyback on the "neural equipment" of young space navy veteran Chip. The alien can perceive everything around Chip (using a psychic potential all humans have but which no human has yet tapped), and implant suggestions in Chip's mind, guiding Chip to areas it wants to explore.

The Ig attack on the Earth is part of some elaborate ritualistic game played by the aliens, who customarily explore the galaxy, discover civilizations and wipe them out as a sort of sport. (The Ig barons are inveterately devoted to blood sports and high risk games, and, if they didn't direct their violence outwards, internal duels and feuds would destabilize their society.) Part of the game is to closely study the victim civilization before exterminating it, so the Baron is as much an anthropologist as an espionage agent.

The Earth opposes the Ig space fleet with a fleet of its own; a private space navy in which the servicemembers elect their own officers from among their ranks. (Didn't they try this in Revolutionary France and Russia?) Many of the novel's characters, including Chip, are spacemen who have just returned to Earth bearing news of a glorious victory over the Ig. Except there really wasn't a glorious victory--the Ig captured the Earth fleet and brainwashed every human survivor of the engagement into believing that they had won. As the novel begins, in a matter of days the Ig are going to wipe out our civilization and the people of Earth have no idea!

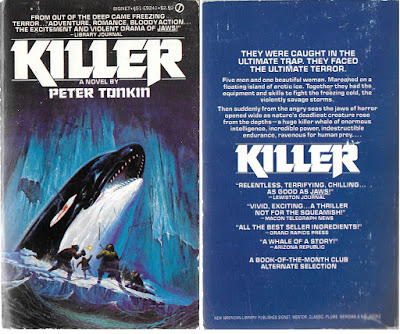

Luckily, a psychiatrist who has taken up the role of defending Earth and can dig up the memories of the space crews knows the truth and he and Chip and a few other people in the know scramble to prepare Earth to resist, while the Ig spy uses its mind control powers to direct other space navy vets against them. I had flashbacks to Killer when Chip found himself in a prison in Antarctica and watched a killer whale attack a seal. In an anticlimactic twist ending the Earth is saved by a palace coup back on Shua--inspired by the example of Earth's anarchist system, revolutionaries impose on the people of Ig just such a system. The obsessive game playing aristocrats will have to stifle their love for blood sports or be zapped by their own Kirlians.

In some ways The Anarchistic Colossus is like Computer Eye, another novel in which computers see all and can chastise people with laser guns, and in which we observe much of the story through the eyes of a nonhuman character. The Anarchistic Colossus also features such Van Vogt staples as mental powers, mind expansion, and secret ubermensch elites working behind the scenes for the benefit of mankind (that psychiatrist has figured out a way to avoid Kirlian scrutiny and do whatever it takes, including blackmail and murder, to save the Earth.)

When I first started The Anarchistic Colossus I didn't think I would be able to enjoy it. The characters are terrible, just a dozen or so guys with short names like Hal and Hank and Mike and Chip and no personality whatsoever. And the style in which the book is written is lame, clumsy with lots of goofy colloquialisms; at times it feels like a stream of consciousness draft that was never polished. But the little lectures on anarchism, psychology and hypnosis, and the way Van Vogt steadily revealed new and different aspects of the Earth and Ig societies, kept me curious. So I, who have a particular interest in Van Vogt, and in libertarian thinking, found the book worthwhile. I doubt I can recommend it to others who do not share these interests.