"We all forgot we were on a ship. We forgot the cataclysm, and the accident, whatever it was...and we even forgot the Earth. We lived as if our entire universe was a hundred kilometers across with a metal sky...."

When I lived in Manhattan I would spend untold hours walking the streets and admiring the skyscrapers and the crowds of aspiring actresses and fashion models, loitering at the river watching the container ships, oil tankers, sailboats and cruise liners bobbing with the tide or cruising up or downstream, and squinting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Greek vases, Roman statues and European paintings and drawings. Life in Central Ohio doesn't offer these same sorts of opportunities, but one Columbus area pastime I can recommend is scrutinizing the bookshelves at Ohio Thrift's various locations. Among the rough of all the romance novels and cookbooks and computer language tutorials one can often find a diamond. For example, I recently discovered a paperback edition of South African athlete, writer and adventurer Robert Crisp's memoir of his service with the Royal Tank Regiment in North Africa, Brazen Chariots. (I read Brazen Chariots in my teens, never forgot it, and having reread it now can confirm it as a great read.)

When I lived in Manhattan I would spend untold hours walking the streets and admiring the skyscrapers and the crowds of aspiring actresses and fashion models, loitering at the river watching the container ships, oil tankers, sailboats and cruise liners bobbing with the tide or cruising up or downstream, and squinting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Greek vases, Roman statues and European paintings and drawings. Life in Central Ohio doesn't offer these same sorts of opportunities, but one Columbus area pastime I can recommend is scrutinizing the bookshelves at Ohio Thrift's various locations. Among the rough of all the romance novels and cookbooks and computer language tutorials one can often find a diamond. For example, I recently discovered a paperback edition of South African athlete, writer and adventurer Robert Crisp's memoir of his service with the Royal Tank Regiment in North Africa, Brazen Chariots. (I read Brazen Chariots in my teens, never forgot it, and having reread it now can confirm it as a great read.)Another recent Ohio Thrift find was a 1975 Fawcett Gold Medal paperback, Phoenix Without Ashes, a novel by Edward Bryant based on a TV script by Harlan Ellison for the TV show he created, The Starlost. I've never seen The Starlost, or even read about it (I'm a cultural illiterate!) but the first page of this paperback (that page where the publisher tells you how awesome the book is and shares ecstatic blurbs if they can get them--Fawcett couldn't get any for Phoenix Without Ashes, Neil Gaiman and Stephen King being too young, I guess) indicates that Ellison conceived of the series, wrote a teleplay (which won an award from the Writers Guild of America) and then, when the show was actually produced, felt that the TV people had screwed it up and ripped him off. There's an acknowledgements page on which a host of writers who have used the "enclosed universe" idea are listed, apparently a prophylactic or retaliatory measure against those who might have the temerity to accuse Ellison of acting like he came up with the "enclosed universe" theme, and then there is a 20-page introduction from Ellison. I decided to skip the intro and read the actual novel first, as if it was just some ordinary novel I might judge on its own merits and not an exhibit in the never-ending case of Harlan Ellison vs. The World.

The first 60 of Phoenix Without Ashes's 160 pages are set in Cypress Corners, a spot of land 100 kilometers wide with a hexagonal sun and moon and a metal dome for a sky. Here lives a sort of 19th-century farming community managed by Elders who preach from a Book that says that premarital sex is bad. Devon and Rachel are in their late teens and in love, but the Creator (a eugenics computer susceptible to manipulation by the unscrupulous Elders) has decreed that Rachel marry some other guy with a better "genetic rating." This part of the book is there to tell you that sex is good, religion is a scam perpetrated by lying hypocrites, and people who believe in religion are sheep--you know, in case you forgot. We get to witness Rachel's erotic dreams, as well as Devon's dreams which cryptically reveal to him the true nature of the universe--poor Devon can't just read the back of the book like we can to see that Cypress Corners is but one component of a generation ship ("space ark") and has to make do with his latent psychic powers.

Going full rebel, Devon pulls a tape out of the Creator computer and tries to convince Rachel's family that their religion is a trick, but he ends up being chased into the woods by a torch-wielding mob. By luck (or through unconscious use of his powers?) he discovers a hatch that leads to the maintenance and control areas of the generation ship, which he finds bereft of crew and in considerable disrepair.

These generation ships are pretty unreliable means of transport, always suffering mutinies like in Heinlein's Orphans of the Sky, or breaking down like in Aldiss's Non-Stop and Malzberg's "Over the Line." And all the stories about them seem to somehow be about religion, mostly saying religion is crap, though in Gene Wolfe's Book of the Long Sun the crap religion obliquely leads the characters to what Wolfe considers true religion--at least that is how I remember The Book of the Long Sun, having only read it once, and that long ago.

Anyway, Devon figures out how to use a space suit and operate an air lock, and then spends 20 or so pages talking to a computer, learning the history of the destruction of Earth five centuries ago in 2265, the creation of the 1,600 km long ark, its populating with three million passengers from dozens of different cultures (each hermetically sealed in its own individual sphere) and its doomed voyage. Yes, doomed--there was an accident 400 years ago that killed the crew and the ship has been off course since then, and, in fact, is projected to crash into a star in five years.

|

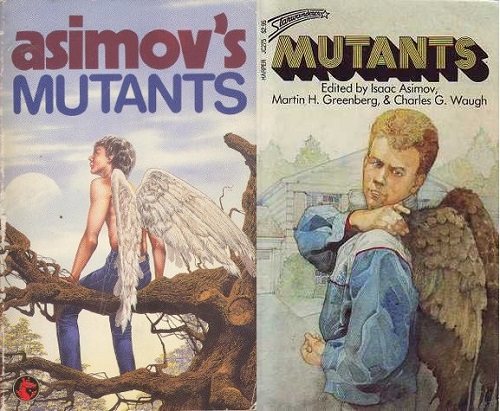

| I like the back cover illustration, spare and evocative |

This novel is not very good. While essentially competent, it is very conventional, a bunch of ideas and themes we've seen before without any additional elements or a distinctive voice to make it fresh or engaging. Phoenix Without Ashes doesn't inspire any emotion in the reader, the characters are stock and forgettable, the style is cold and bland, and the pace is slow and unvaried--each character's every little movement is described, so much of the novel reads like a mechanical record of stage directions transcribed by somebody watching a TV show. Structurally it has problems--as the first episode of an episodic story it lacks climax and resolution and suffers from long expository sections--and I for one don't find Amish-Mennonite type environments very interesting; maybe the constraints of TV production or the desire to attack religion lead to the low-tech setting, but I would have preferred some kind of strange futuristic or otherwise speculative setting.

**********

|

| UK edition |

This intro, titled "Somehow, I Don't Think We're in Kansas, Toto," has the distinctive Ellison voice and thus is more readable and emotionally involving than Bryant's novel; it should interest people who like stories about Hollywood shenanigans and those who enjoy hearing Ellison insult people. Most interesting to me was the fact that the Fugitive angle, seemingly tossed in at the end of Bryant's novel, was apparently the germ that started the whole project--we are told that a "West Coast head of taped syndicated shows" requested a meeting with Ellison because, he said, he wanted "the top sf writer in the world" to write "a sort of The Fugitive in space."

Bryant gets a page and a half to introduce himself, and his last line is "And I'm a dilettante inland lay-authority on sharks," which made me smile because one of Bryant's more memorable stories is about sharks.

While not offensively bad, I can't really recommend Phoenix Without Ashes. Perhaps people interested in Bryant's career (this is his only novel listed at isfdb) and those who have seen The Starlost (Ellison says he never saw any episodes after the first, which he calls "the abomination," but that friends call him up to tell him how much they like it after catching it in reruns) will find it intriguing, and Ellison completists may want to own "Somehow, I Don't Think We're in Kansas, Toto."