No doubt religion had to be invented for such gentle and simple minds, and perhaps they can't get along without it any more than I can get along with it.

|

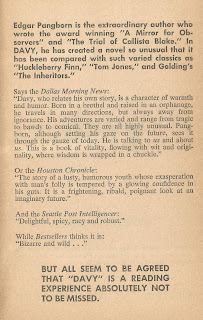

| Squint or click to check out the Foster illo or the gushing blurbs |

Published in 1964, Davy appears to have been well-received by the press, who declared it ribald, spicy, racy, terrifying, and intelligent; by major science-fiction writers like Robert Heinlein and Theodore Sturgeon; and by some guy I never heard of, Clark Kinnaird, apparently a newspaper columnist. The blurbs on my Ballantine paperback (U6018) hint that the book is full of jokes and sex. Well, like everybody (except maybe Philip Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield), I like to laugh and I like to have sex, so maybe I'll enjoy Davy as much as did Messrs. Heinlein, Sturgeon and Kinnaird. Let's hope so!

Davy is another one of those post-apocalyptic stories; we readers of science fiction run into a lot of these. This one is laced with satire (like Spawn of the Death Machine), famous places are known by corrupted names (like in "Magic City"), its characters have been reduced to a pre-industrial lifestyle and everybody is worried about mutants, thanks largely to an oppressive religion that is harshing everybody's buzz (like in Re-Birth.) In Davy (as in the three works I just mentioned) the apocalypse took place over a hundred years ago, unlike in False Dawn or No Blade of Grass, in which the characters are trying to survive in the period immediately after the collapse of 20th-century society. Davy's world is the result of a 20th-century nuclear war followed by plagues; somehow the sea levels also rose. (When it rains it pours, I guess.)

I'd be lying if I didn't admit that I'm a little tired of all this post-apocalyptic business, but when I'm at the art museum I don't say "cripes, another statue of a naked person from those Greeks and Romans" or "oh, big surprise, a roomful of pictures of the Virgin Mary from those Medieval and Renaissance painters"--I recognize the intrinsic interest of these subjects, and try to judge each work on its individual merit. I'll try to do the same for Davy.

|

| This cover strongly conveys the tone and content of the novel |

Most of the 260-page novel takes place in upstate New York and New England, where Pangborn spent his college years and writing career. The area is split up into many small countries that don't really get along, but all recognize the same church, the Holy Murcan Church, which tries to limit the excesses of wars and maintain some kind of social order by such policies as regulating 20th-century artifacts (gunpowder is outlawed), forbidding ocean exploration, and demanding the death of all mutants. I guess this is supposed to remind you of the international political structure of medieval Europe. People live in walled towns because of bandits and aggressive mutant predators, like fifteen-foot-long great cats. Davy, born in a brothel to parents he doesn't know, spends his early childhood in an orphanage. As a teen he is a bond servant in the town of Skoar in the country of Moha. He runs away the same week a war breaks out between Moha and Katskils; before he escapes he makes sure to have sex with his boss's beautiful daughter Ennia.

On the road to Conicut and Vairmont Davy hooks up with deserters from the Katskils army. After some adventures with them he joins a musical troupe/band of snake oil salesmen and travels around, playing a French horn he stole from a mutant he befriended early in the book. Finally he gets involved in the politics of the big city of Nuin (I think this is Boston), marries Nickie, a beautiful aristocratic woman, and befriends Dion, the enlightened ruler.

|

| I love this exciting cover, but it does nothing to communicate the feel of the book |

Pangborn seems to share Heinlein's individualistic attitude; Davy denounces communism, calling it a "spooky religion," Christianity's younger brother. On the same page Davy reminds us that "only individuals think," and later one of the book's mentor figures says that "loners" may be the only people who sincerely like people. (I guess this is one of those Oscar Wilde-style paradoxes.) The whole book romanticizes "loners" and free-thinkers, and, not surprisingly, Davy was a preliminary nominee for a Prometheus Award in 1989.

Heinlein and Sturgeon, in their writing, celebrate sex, and express a deep skepticism of religion and traditional mores in general. (Need I remind you of Sturgeon's story about incest?) Davy shares these themes. Many pages are devoted to demonstrating or just plain telling you that religion is not only a scam that gives comfort to the foolish and ignorant, but can hold back society and make the lives of individuals worse. Memorable examples include a character who forgoes the joys of sexual intercourse because of his religion, and a scene in which people get killed by one of those huge felines because their religious convictions prevent them from dealing rationally with the mutant cat.

The colony in the Azores (dubbed Neonarcheos) is reminiscent of the utopias we see in Sturgeon's work and the settlements and new nations we often see in Heinlein's work. Neonarcheos has unconventional sexual practices: there is a group marriage (a family of two men and one woman), while Dion sexually desires Nickie (his cousin), who is 15 years his junior and whom he knew when she was a baby (this kind of thing happens in Heinlein's Door into Summer and Time for the Stars.) The women of Neonarcheos run around topless, and what could be more utopian than that?

|

| Ecstatic blurbs from the first page of my copy of Davy |

I don't think I actually laughed at the jokes, but some are OK. Many are reflections of how our world (the "Old-Time") bewilders the people of the future. One of Davy's fellows describes at length a retractable ball point pen; nobody in Davy's world can figure out what it is. Davy finds the iconic personages and classic literature of our civilization confusing: "St. George and his everloving cherry tree, or poor Julius Caesar dividing his gall in three parts so as not to offend his friends, Romans countrymen...."

There is also low humor, like jokes about farts, and there is a slapsticky set piece in which a teen-aged Davy, interrupted while stealing clothes, is hiding behind a door during a seance. He puts on a fat woman's voluminous white dress and bursts into the dimly-lit ceremony, scaring the seance participants who think he is a ghost. In the same way that Davy thinks a fat woman's huge breasts are funny, he also thinks a skinny woman's flat chest is funny, and finds it amusing that the flat-chested skinny woman runs naked out of the house where the seance is being held and into the center of the town where everybody can see her. Davy is full of jokes that feel like jokes you've been hearing all your life.

A lot of these jokes are probably not going to receive the feminist seal of approval (thgere's even a mother-in-law joke), and I think the sex scenes may be in the same boat. Davy loses his virginity to Ennia on page 84 in a "no means yes" scene which nowadays may raise eyebrows as efficiently as it quickens heartbeats:

And she whimpered: "Ah no!"--in a way that couldn't mean anything except: "What the devil would be stopping you?"--and twisted her loins away from me, only to remind me I must use a little strength in this game.

Davy's second sexual partner (page 135) also likes to wrestle as foreplay:

"...come take me. You'll have to work for it...." I worked for it, wrestling her at first with all my strength and getting no breaks at all until until the struggle had warmed her up into real enjoyment. Then all of a sudden she was kissing and fondling instead of fighting me off....Pangborn doesn't use phrases like "rough sex" or "playacting rape," but it certainly seems like that is what is going on.

These sex scenes are probably the best scenes in the book--they inspire some kind of feeling and thought in the reader. In contrast, the action scenes are boring, and all the anti-clericalism, and many of the jokes, are banal. There is also way too much travelogue in the book, descriptions of towns and their history that seem pointless.

As a whole, Davy is just OK... at times it felt quite boring. I sympathize with its attitude about sex and religion, but the pace is slow and the novel feels long, and, as I have said, many scenes and ideas feel tired, like I've read or seen them before. (How many movies and TV shows have included a scene with a snakeoil salesman?) I didn't find the characters interesting, and I didn't care what happened to them and I wasn't very curious about what would happen next or how the story would turn out (we know how the story turns out from the beginning.) The novel isn't structured to have heightening tension and then come to a climax; the tone doesn't ever really change. If anything, the novel gets more tedious in the last 80 or so pages after Davy decisively turns against religion and (perhaps) finds his father on page 182.

The extravagant praise we see all over the book is perhaps largely the product of its time period; jokes about farts, scenes of rough sex play, and relentless attacks on religion presumably felt fresher and braver in 1964 than they do today, and no doubt Heinlein and Sturgeon were eager to cheer on a kindred spirit.

I think an interesting question to ask about Davy is, why (or to what extent) is it a science fiction novel? Fawning critics compare Davy to Tom Jones (18th century) and Huckleberry Finn (19th century) and Davy's adventures, like stealing clothes from a village, having sex in the woods, and witnessing religious zealotry and wars fought with spears, fit perfectly into some medieval, Renaissance, or Early Modern setting. There's no aliens or telepathy or high technology in Davy, and the atomic war/mutants stuff is used surprisingly sparingly. I guess the post-apocalyptic setting allows Pangborn to combine his pre-industrial concerns with long passages about the New York, Pennsylvania and New England with which he is so familiar.

So, a disappointment. My eagerness to read the other two Pangborn novels I recently aquired, West of the Sun and The Judgement of Eve, has been seriously diminished.

**********

The back of my edition of Davy has a lot of interesting advertising.

The "A Selection of Fiction" page includes writers who live on the porous border between SF and mainstream fiction, like Ray Bradbury, Doris Lessing, Anthony Burgess, and Nevil Shute. The "A Selection of Non-Fiction" page gives one a sense of the historical moment in which Davy was published, its political and social controversies: there's The Complete Book of Birth Control, sponsored by Planned Parenthood, Martin Luther King's Stride Toward Freedom, books on prostitutes, pornography, and psychoanalysis. My favorite, though, is the capsule description of Dan Mannix's Memoirs of a Sword Swallower; I find the phrase "Flamo the Great exploded that night in front of Krinko's side show" hilarious--funnier than any joke in Davy.