"The Life-Masters" by Edmond Hamilton

This is a rare story, never having been reprinted until 2011 when it was included in The Universe-Wreckers, the third volume of Haffner Press's The Collected Edmond Hamilton. Soon I will join the elect few people living today who have read this tale, and the even smaller number who have decided to devote a portion of their short lives to writing about it!

"The Life-Masters," which is a little on the long side (isfdb calls it a novelette) has four chapters. You may recall that I said that much of Hamilton's 1928 "The Polar Doom" read like a newspaper account or a brief history, and that much of his 1932 tale "A Conquest of Two Worlds" read like an encyclopedia entry about a military campaign, and Chapter 1 of "The Life-Masters" is in that same vein, a sort of journalistic account of how, one day, a thick carpet of gray slime appeared on all the world's seashores. Scientists come to believe it is protoplasm, the sort of life that first appeared on Earth eons ago and evolved into the diverse living things that inhabit the world today. Chapter 2 follows the horrifying adventures of a chap who goes to Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan (as I did so many times myself in those halcyon days when I lived in New York) a few days after the appearance of the goo, just as it becomes vigorous and voracious and begins oozing down streets and alleys, snatching people with pseudopods and devouring them, enveloping the whole island. Millions of people are killed as similar attacks take place on coasts all over the planet and the slime proves impervious to all weapons turned against it.

In Chapter 3 we follow a scientist as he flies a plane to an island off New England--he takes off just before the attack described in Chapter 2 begins. The world scientific community has sent this guy to the island to contact the world's greatest biologist for help figuring out what that slime is all about. Once on the island he learns the astonishing, the mortifying truth! That biologist had assembled a team of scientists with the goal of discovering then origin of life on Earth. A few billion years ago protoplasm first appeared from sea silt when worked upon by cosmic rays, a process that took millions of years. The biologist and his team constructed a "condenser" that could concentrate these cosmic rays and reproduced that prehistoric phenomenon, producing protoplasm from sea silt in short order. They discovered that they had to concentrate just the right kind of rays, because if rays of another wavelength were concentrated, the protoplasm was instantly killed, reduced to mere dust.

Having created life where there was none before went right to the heads of these eggheads, and they declared themselves like gods and began acting like gods. They built a supersized ray condenser that could make protoplasm arise in every body of salt water on the Earth, and put into action a diabolical three-part plan: first, let the protoplasm exterminate all life in the world, second, kill the protoplasm, then third, repopulate the planet with new and improved forms of life designed by themselves. (The mad scientists thought the sheer cliffs of their island too steep for the protoplasm to reach them.)

The scientist who arrived in the plane learns all this after being locked up by the mad scientists, and luckily in Chapter 4 he escapes and changes the setting on the condenser, killing all the protoplasm and saving the world.

This is an acceptable mad scientist story with some fun images of people getting killed and lots of speculative science about evolution and radiation--much of Hamilton's body of work revolves around radiation and evolution, as we have seen over the course of this blog's life.

"The Murderer" by Murray Leinster

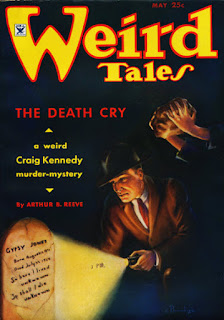

Sitting above the name of my homeboy Hamilton on the cover of this issue of Weird Tales is that of Murray Leinster. Like Hamilton's "The Life-Masters," Leinster's "The Murderer" is sort of rare, not having been reprinted until 1994 in 100 Wild Little Weird Tales. Unlike Hamilton's story, which is almost 19 pages long, "The Murderer" is brief, fewer than five pages.

After murdering his rich miserly uncle so he would get the inheritance the killer hurried away from the scene of the crime, only to realize he had left his cigarette case in the murder room--if the fuzz finds it, it will tie him directly to the murder. Back in his uncle's place, fumbling about in the dark, afraid to use his flashlight lest the neighbors see it, the murderer searches for the cigarette case but it keeps eluding his grasp, and he also gets the impression that his dead uncle is moving, if only slightly. The murderer is driven insane by fear and knocks over the telephone, leading the operator to send the cops to the house to see what is up. It turns out that what was shifting the corpse's clothes and limbs and moving around the critical cigarette case move was the uncle's large playful cat.

Acceptable filler. The illustration on the first page of the story totally spoils the story's mystery, depicting the cat trying to play with the disturbed murderer.

"The Red Fetish" by Frank Belknap Long

I'm calling this a rare story because it has only been reprinted in the 1931 British hardcover anthology edited by Christine Campbell Thomson, Switch on the Light, Centipede Press's $450.00, 1100-page Long collection from 2010, and a print-on-demand book from Wildside Press.

Like Leinster's "The Murderer," this is a more or less realistic black humor and horror piece, but the humor and especially the horror are much more intense. Two men have been shipwrecked on an island with no fresh water and no fruit-bearing plants, and they are enfeebled by hunger and near death from thirst. Long dwells on their doleful physical and psychological condition, coming back again and again to such items as their narrow wrists and ankles, their blackened lips, their protruding ribs, etc. The men are almost insane, and each often thinks of murdering the other while fearing the other plans his own murder. The humor of the story comes from the things the men think and say in their horrible situation, and does not undermine the bleak atmosphere or tension of the story.Six or seven miles away is an island with fresh water and fruit trees, but it is reputedly inhabited by head-hunting cannibals, so the men have delayed swimming over to it. By the time they finally resort to risking the passage to the cannibal island, they are quite weak. They are nearing the cannibal island when one man is torn to pieces by sharks. The other makes it to the island, where, some hours after he has made landfall and drunk his fill of fresh water, he is confronted by the cannibals. He expects to be tortured, killed and eaten, but he is in luck: his comrade's head washed up on the beach before he did, and the natives consider it a gift from the survivor, whom they welcome as a friend and benefactor, maybe even a god. For three months they give him the run of the island, and then a ship picks the castaway up to take him back to civilization. Unfortunately, since the moment he saw his companion's severed head in the hand of one of the cannibals, he has been insane.

I have often been pretty hard on Long's work, but this is actually a pretty good story, with Long doing a decent job of describing the men's mood swings and despair, their suffering on the beach, their desperate swim and the survivor's reaction to finding potable water and then being surrounded by the cannibals. "The Red Fetish" really held my interest. Thumbs up!

"A Matter of Sight" by August Derleth

This two-and-a-half-page story was reprinted in the 1948 Derleth collection Not Long For this World and its 1961 paperback abridgement, and more recently in the 2009 collection That is Not Dead: The Black Magic and Occult Stories."A Matter of Sight" is a lame filler story, a waste of time I have to give a thumbs down to. The narrator is riding a train in England. A man with dark glasses sitting next to him speaks to him, claiming he has the power to see into the fourth dimension. With this power he can see into the past of the place in which he is located. By travelling the world he has seen, in action, Alexander, Caligula, Cleopatra, Cagliostro, and many others. He also, apparently, can read people's minds and see for long distances, through obstructions. Anyway, right before he and the narrator part at the terminal the man in glasses says that he was captured by the Chinese during the Boxer Rebellion and lifts up his spectacles to show that his captors tore out his eyes.

Derleth here just jams together two ideas which don't really have much to do with each other, and he doesn't build an interesting story or a convincing character around either idea. Not good!

**********

I think there were 115 issues of Weird Tales published during the 1930s, and now I can cross the first of them off my list. We'll cross off a few more in our next episode.