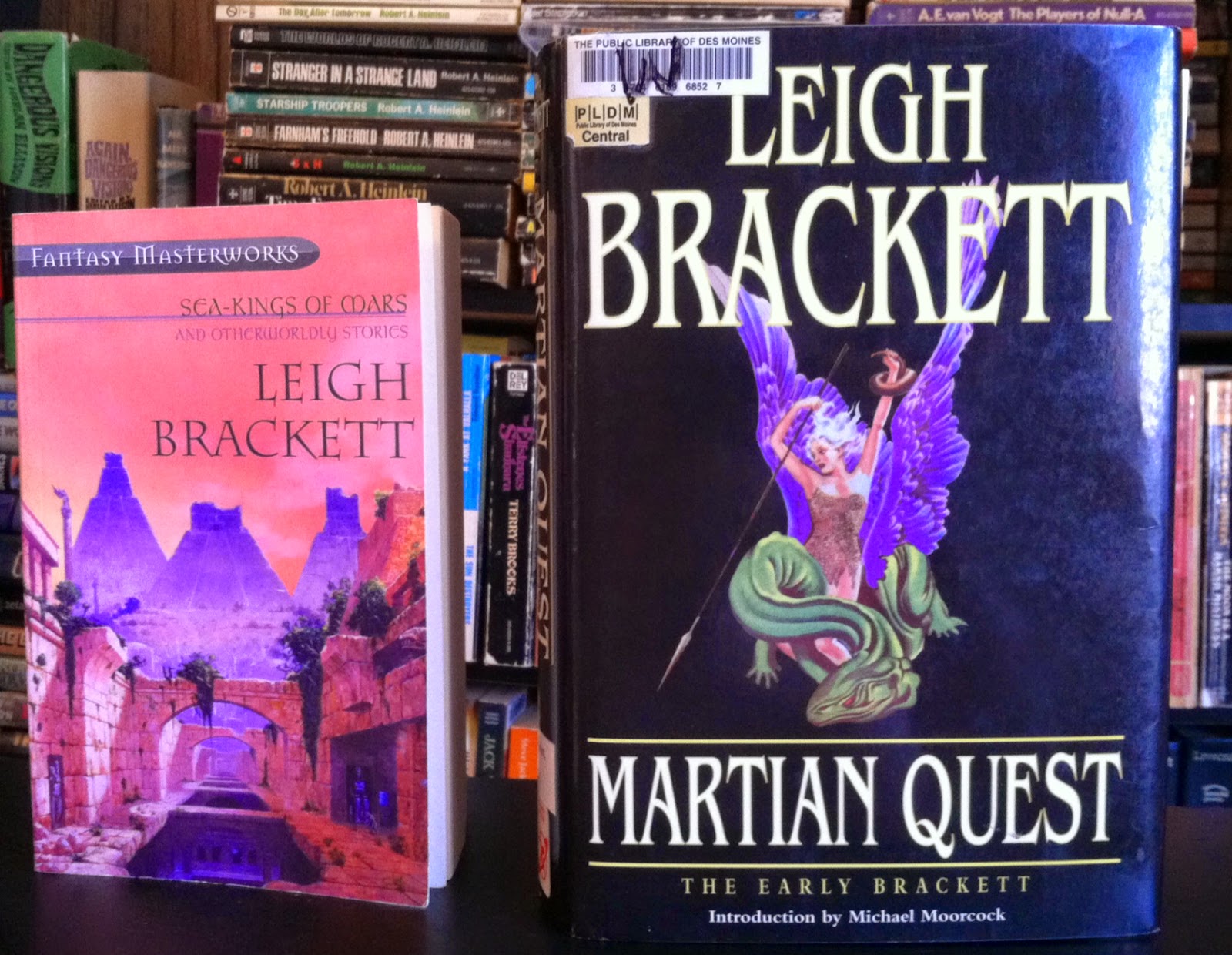

Let's travel back in time to the 1940s, and across the aether to our sister planet, through the medium of three tales by Leigh Brackett, and see what is going on on that world of mystery we know as Venus! These stories first appeared in pulp magazines, where they were the lead stories; Brackett's name, apparently, sold copies. I read them this week in my copies of Gollancz's 2005 collection Sea-Kings of Mars and Otherworldly Stories (Fantasy Masterworks 46) and Haffner Press's 2002 Martian Quest: The Early Brackett. You frugal types can get all three of the stories I'm talking about today in a single four dollar e-book from Baen entitled Swamps of Venus, complete with the kind of cover art Baen is famous for.

Earthman Roy Campbell is a renegade! When the government seized his family's farm and flooded the area to create a reservoir so it could generate hydroelectric power for factories, Roy took up a life of interplanetary crime. He didn't want to work in a city like a sheep ("He'd tried it, and he couldn't bleat in tune"), so he became a space wolf, hijacking space ships and selling the hot goods to fences on Venus. When the space patrol is hot on his trail he hides out among a tribe of peaceful Venusian natives.

But now the Terra-Venus Coalition Government is about to pull the same eminent domain chicanery on Roy's Venusian buddies! The government is going to relocate the tribe to town, drain their swamp, and extract coal, petroleum and other valuable resources from the area!

Roy, who somehow has a better space ship than the government fleet does, blasts off from the swamp, evades the space patrol, and visits Romany, a private space station that orbits Venus and is made up of dozens of decrepit old space ships welded together. Romany is the home of thousands of space gypsies, people of many species and races who have been driven from their homes like Roy and his Venusian friends. Romany, Roy finds, is in the midst of a civil war between those who want to continue being a refuge for interplanetary outcasts and those who want to come out of the shadows and integrate Romany with the Terra-Venus government. Part of getting along with the government is handing over space pirates like Roy to the space patrol, which is on its way!

"Citadel of Lost Ships" is about ethnic minorities ("little people") who use their special powers to try to resist the "progress" and "efficiency" pursued by mainstream society. Among the various aliens on Romany are psychics from Titan who can create impenetrable force fields and a harper from Callisto whose music stuns people. Even Roy and the human girl from Romany with whom he falls in love because of her musical voice, pale heart-shaped face and "long and clean-cut body" which has "the whiteness of pearl," are mystical minorities because of their Celtic blood: "'The harp of Dagda,' whispered Stella, and the Irish music in her voice was older than time. The Scot in Campbell answered it."

In the end Roy sacrifices his space ship and allows himself to be captured so that Romany and his Venusian swamp-dwellers can remain independent. Brackett gives us the hope that Roy, who has money secreted away somewhere and apparently is some kind of folk hero, will be able to get out of prison soon and be reunited with Stella.

This story is entertaining, and I like all the space ship stuff, particularly the idea of the space station built up out of old ships, and the story's attitude about progress is interesting. Roy, the Venusian swamp-dwellers, and Brackett herself admit that the new industrial society is inevitable, and will be safer and wealthier, but they care more about freedom and independence than safety and wealth and would like to be left alone. Government seizures of land and relocation of communities "for the common good" were presumably on many people's minds in 1943; a gander at the website of the Center For Land Use Interpretation informs you that during the 1930s and early 1940s numerous communities in New England and New York were condemned and flooded to provide drinking water for Bostonians and New Yorkers, while Wikipedia tells us that over 1,000 families were relocated by the Tennessee Valley Authority to make way for the Fontana Dam, which started construction in 1942.

The weakness of the story is that the pace is a little too fast, and there are perhaps too many elements jammed into its short length (36 pages). The Titanians and the Callistan, for example, aren't foreshadowed or developed, they just suddenly appear deus ex machina style to use their powers to resolve the plot. And the fact that Roy and Stella are Celts is raised on one page, mentioned on the next page, and then dropped. Some may also complain that Brackett is taking the easy way out and softening the story's drama by having everybody use nonlethal weapons (Roy, Stella, and the government agents shoot at each other with needle guns that use anesthetic needles.)

It is interesting to compare "Citadel of Lost Ships" with Henry Kuttner's "Raider of the Spaceways" from 1937. Both are about a space pirate on Venus, both include a cast of characters from various planets, and both include interesting space battles. But whereas in Kuttner's story the pirate is the villain, the Space Patrol is good, and our protagonist is the son of the President of a future version of the United States, in Brackett's tale the hero is the pirate, and he's a poor boy who's been disenfranchised by the government and is pursued by its agents. Kuttner's plot holds together a little better; the thing that saves the day in the end is foreshadowed early in the story, unlike Brackett's psychics and harper, who appear in the fourth chapter of a five chapter story.

But now the Terra-Venus Coalition Government is about to pull the same eminent domain chicanery on Roy's Venusian buddies! The government is going to relocate the tribe to town, drain their swamp, and extract coal, petroleum and other valuable resources from the area!

Roy, who somehow has a better space ship than the government fleet does, blasts off from the swamp, evades the space patrol, and visits Romany, a private space station that orbits Venus and is made up of dozens of decrepit old space ships welded together. Romany is the home of thousands of space gypsies, people of many species and races who have been driven from their homes like Roy and his Venusian friends. Romany, Roy finds, is in the midst of a civil war between those who want to continue being a refuge for interplanetary outcasts and those who want to come out of the shadows and integrate Romany with the Terra-Venus government. Part of getting along with the government is handing over space pirates like Roy to the space patrol, which is on its way!

"Citadel of Lost Ships" is about ethnic minorities ("little people") who use their special powers to try to resist the "progress" and "efficiency" pursued by mainstream society. Among the various aliens on Romany are psychics from Titan who can create impenetrable force fields and a harper from Callisto whose music stuns people. Even Roy and the human girl from Romany with whom he falls in love because of her musical voice, pale heart-shaped face and "long and clean-cut body" which has "the whiteness of pearl," are mystical minorities because of their Celtic blood: "'The harp of Dagda,' whispered Stella, and the Irish music in her voice was older than time. The Scot in Campbell answered it."

In the end Roy sacrifices his space ship and allows himself to be captured so that Romany and his Venusian swamp-dwellers can remain independent. Brackett gives us the hope that Roy, who has money secreted away somewhere and apparently is some kind of folk hero, will be able to get out of prison soon and be reunited with Stella.

This story is entertaining, and I like all the space ship stuff, particularly the idea of the space station built up out of old ships, and the story's attitude about progress is interesting. Roy, the Venusian swamp-dwellers, and Brackett herself admit that the new industrial society is inevitable, and will be safer and wealthier, but they care more about freedom and independence than safety and wealth and would like to be left alone. Government seizures of land and relocation of communities "for the common good" were presumably on many people's minds in 1943; a gander at the website of the Center For Land Use Interpretation informs you that during the 1930s and early 1940s numerous communities in New England and New York were condemned and flooded to provide drinking water for Bostonians and New Yorkers, while Wikipedia tells us that over 1,000 families were relocated by the Tennessee Valley Authority to make way for the Fontana Dam, which started construction in 1942.

The weakness of the story is that the pace is a little too fast, and there are perhaps too many elements jammed into its short length (36 pages). The Titanians and the Callistan, for example, aren't foreshadowed or developed, they just suddenly appear deus ex machina style to use their powers to resolve the plot. And the fact that Roy and Stella are Celts is raised on one page, mentioned on the next page, and then dropped. Some may also complain that Brackett is taking the easy way out and softening the story's drama by having everybody use nonlethal weapons (Roy, Stella, and the government agents shoot at each other with needle guns that use anesthetic needles.)

It is interesting to compare "Citadel of Lost Ships" with Henry Kuttner's "Raider of the Spaceways" from 1937. Both are about a space pirate on Venus, both include a cast of characters from various planets, and both include interesting space battles. But whereas in Kuttner's story the pirate is the villain, the Space Patrol is good, and our protagonist is the son of the President of a future version of the United States, in Brackett's tale the hero is the pirate, and he's a poor boy who's been disenfranchised by the government and is pursued by its agents. Kuttner's plot holds together a little better; the thing that saves the day in the end is foreshadowed early in the story, unlike Brackett's psychics and harper, who appear in the fourth chapter of a five chapter story.

|

| I guess this is meant to illustrate our story (?) |

"Terror Out of Space" (1944)

Venus has passed through a cloud of cosmic dust, and male inhabitants of the planet are going insane, committing murder and even worse crimes! Operatives from the Special Branch of the Tri-World Police, Lundy and Smith, have captured one of the aliens from the cloud that are driving every guy nutso, and also have Farrell, one of the victims, in protective custody. But while they are flying back to base the alien uses its special powers to drive Smith and Farrell so bonkers that the aircraft the taxpayers have provided them crashes into the black Venerian ocean.

Smith and Farrell are killed, and Lundy, in his space suit, walks the ocean floor towards the shore. He comes upon an ancient road that leads to a city that sank beneath the waves ages ago. Nowadays the city is inhabited by plant people. The cosmic alien has driven the male plant people insane, and the female plant people request Lundy's help. Lundy provides them succor, which involves fighting some voracious plant monsters that come out of a fissure in the ocean floor (with two blasters, John Woo style) and catching that cosmic alien again.

"Terror Out of Space" reads like a draft that could have stood a few revisions. There are lots of elements and ideas in the story, maybe too many, and the clipped, rapid style, full of metaphors and abstractions, is a little difficult to follow. Some of the similes could have been toned down; at the end of Chapter 1 we are told that Lundy "was colder than a frog's belly in the rain...." Two pages later, in the start of Chapter 2, we read that Lundy is "cold as a toad's belly and as white." In Chapter 4 Lundy is cold again, but happily Brackett doesn't tell us he's as cold as a salamander's belly--this time he's "as cold as a dead man's feet and just as numb."

The cosmic alien is described as a three-inch-long engraved and fluted crystal cylinder, and it is not clear how it moves. Until the end of the story I wasn't even sure it ever moved of its own volition; through most of the story it is captive in a little net, or (I thought) driven by ocean currents. The crystal creature generates illusions in the minds of men--they see the most beautiful woman they can imagine, their dream girl, and they do whatever she says, despite whatever harm it causes themselves or others. This dream girl wears a veil over her eyes, or keeps them closed, and when she opens them the man is driven permanently insane or simply dies. Because when his dream girl opens her eyes, a man sees that behind the lids is nothing, that his dream is nothing more than a dream.

At the end of the story it is revealed that the crystal aliens have no idea they are causing so much trouble, because pain and death were never factors in their existence out in space, and they've never been on a planet before. They like being worshiped, and were just playing around with the people of Venus as if they were toys. This carefree attitude doesn't quite jive with the other thing we learn about the cosmic crystals at the end of the tale; being on Venus is painful to them, the gravity, which they never experienced out in space, is crushing them and will soon kill them. The wave of madness sweeping Venus will soon burn itself out, and Lundy's detective work and plant monster blasting was essentially unnecessary.

In "Terror Out of Space" Brackett seems to be saying something about gender roles and about men's view of women, and also about the way women can use their sex appeal to manipulate men and destroy stable family life. We see how life is lived among the plant people, whom Brackett intends us to be sympathetic to. The plant women spend their time tending flower beds of seedlings--these flowers are their children who are not yet old enough to leave the sand. Lundy denounces the cosmic alien for causing men to leave behind their wives and kids, and we watch as the alien commits this very crime against the entire plant people community-- the plant men abandon their wives and children to chase a sexy illusion, an illusion that leads them straight into the jaws of their deadly enemies. Perhaps "Terror Out of Space" should be seen primarily as a criticism of home-wrecking femme fatales and a lament over how dumb men can be when they see a pair of pretty legs. You could call it a conservative message that endorses traditional gender roles; I recall that Alpha Centari or Die! also seemed to be endorsing traditional sex roles.

It's a good idea to write a story about how men's fantasies of the ideal woman can wreck their lives, and how men will do dangerous or stupid things to impress women, but I didn't find the story to be very well-executed. The whole thing, from the action scenes to the way the plot elements fit together, felt abstract, impressionistic, dream-like. Maybe that was Brackett's intention? Personally I prefer things to be sharp and clear, and so I have to give this one a (marginal) thumbs down.

It's a good idea to write a story about how men's fantasies of the ideal woman can wreck their lives, and how men will do dangerous or stupid things to impress women, but I didn't find the story to be very well-executed. The whole thing, from the action scenes to the way the plot elements fit together, felt abstract, impressionistic, dream-like. Maybe that was Brackett's intention? Personally I prefer things to be sharp and clear, and so I have to give this one a (marginal) thumbs down.

Of the Venerian stories we are discussing today, this is the best; plot and style are smooth, the action scenes and characters are interesting.

David Heath is an Earthman on Venus. There is a weird site on Venus, where sits the radioactive Moonfire, apparently a fragment of Venus' long lost satellite. The natives of Venus, whose language has no word for "radioactive," believe that the Moonfire is part of a fallen god and that those who visit the Moonfire will achieve godlike power. Heath himself once quested for the Moonfire, but only reached its fringes, and then fled, to live as an emaciated wreck in a tavern for three years, drunk out of his mind every day!

A brave barbarian, Broca, and his girlfriend, Alor, whose "body was everything a woman's body ought to be...wide-shouldered and leggy..." demand to be guided to the Moonfire by Heath, so our hero sobers up and off they go. Broca wants to make himself a god and Alor his goddess, and, for his part, Heath wants to use the power of the Moonfire to create a simulacrum of his lost girlfriend, Ethne. He's even named his ship after Ethne.

For some reason, there are no space ships, ray guns, computers, radios or even internal combustion engines in this story; the Ethne is a sail boat and Heath, Broca and Alor have to use a sail to get across the ocean and then scull their way through the monster-infested and fever-inducing swamp that surrounds the Moonfire. They are pursued by the merciless priesthood of the Moon, whose ship has an emerald green sail. This whole sequence is well done, real adventure stuff. During the perilous trip Alor loses interest in the brutish Broca and falls in love with Heath, adding human drama.

The Moonfire gives those who remain in its environs the ability to manipulate matter, to make their dreams come true. As in "Terror Out of Space," Brackett suggests that men's foolish dreams can ruin their lives and the lives of those who love them; the crater around the Moonfire is littered with the bodies of men who lived in dreamworlds of their own creation and died of starvation rather than leave. Heath tries to create his dream vision of Ethne, but realizes it is Alor, a flesh and blood human being, whom he truly loves. Broca creates a huge castle full of slavish courtiers and tries to achieve revenge on Heath for stealing his girl, but Heath and Alor escape to live happily ever after. It would be easy to see this business of the Moonfire as being Brackett's attack on drugs, masturbation or even (ulp!) escapist literature as cheap and artificial ways of producing happiness which only serve to get in the way of true happiness, which comes from mature love relationships with other human beings.

I'm glad I read this one last, as it is by far the most satisfying of the three stories.

**********

Recently, Jesse of Speculiction reviewed Leigh Brackett's "Black Amazon of Mars" and made the bold assertion that Brackett is superior to her towering predecessor in the planetary romance field, Edgar Rice Burroughs. He has also posted a hostile review of Edgar Rice Burroughs' first novel, A Princess of Mars, one of my favorite books. I like Brackett, and I like "Black Amazon of Mars," and I certainly recommend that fans of Burroughs read "Black Amazon of Mars," but I'm going to have to register some disagreement with Jesse here.

I can certainly see why Jesse, whom it appears believes literature should instill progressive values in readers and raise cultural standards, would prefer Brackett to Burroughs. Brackett is a woman, and her hero, Erik John Stark, is non-white, and Brackett includes more proactive and heroic women in her stories than does Burroughs, so all the identity politics points are on Brackett's side. And Burroughs certainly celebrates martial prowess (I recall John Carter in his later adventures telling us he enjoys life-or-death fighting!), aristocracy and imperialism (though both Carter and Tarzan do go native, preferring the violent barbaric world they come to dominate to the modern Western world, even as they bring some of the cultural benefits of Western society to the barbarians), while Brackett's heroes are working-class and Brackett is skeptical of elites.

Beyond these political considerations, Brackett, as Jesse points out, has a more modern style than Burroughs, and, writing decades after Burroughs began his own career, has a modern noirish or "hard-boiled" sensibility. Brackett's stories also tend to be more believable than Burroughs', in which Carter and Tarzan single-handedly fight off dozens of foes at a time in close combat.

However, for me, Burroughs is the superior writer. I recognize that it is not for everybody, but I love Burroughs' old-fashioned style, which is clear and straightforward, but, as Jesse suggests, somewhat formal. I also enjoy his Victorian attitudes. One reason I read science fiction and fantasy books is to explore a different world, and nowadays every TV show, every film, every newspaper, and every college class goes out of its way to decry racism, sexism, and homophobia and promote the interests of women, minorities and "the environment." Burroughs' books, which simply accept or actively celebrate values we are now reminded tirelessly to abhor, are a window on a different world. Similarly, nowadays "sophisticated" people are all cynical, sarcastic and "ironic," while Burroughs' books are sincere and optimistic. Carter has a clear sense of right and wrong, loves Dejah Thoris utterly, and declares more than once in his career, "Where there is life, there is hope!" Paradoxically, Burroughs' books, some published over 100 years ago, feel fresh.

Jesse hints at this paradox when he likens Burroughs' work to a sexy dangerous rebel, which in some ways is odd, because Burroughs' values were mainstream values, and it is the modern cynics who are (or purport to be) the sexy rebels. I also think Jesse is mistaken when he suggests Burroughs' work is empty or meaningless. In the same way that the Brackett stories I talked about above are adventure tales that try to say something about topics like the role of the individual in society, what constitutes freedom, how men and women should deal with each other and what role men and women have in society and family, some of Burroughs' work addresses important topics like the role of the state, eugenics, religion, and the virtues and pitfalls of modern and primitive societies. Jesse's issue may not be that Burroughs fails to address life and the human condition, but that Jesse simply doesn't agree with what Burroughs has to say.

(Perhaps, on the subject of the racism of Burroughs' work, I should point out that in the second Barsoom novel, Gods of Mars, we meet the white men of Mars, who are arrogant creeps who have been bamboozling the people of Mars for centuries with their self-serving and bogus religion. By current standards the Barsoom books are certainly racist, as Burroughs shows that different cultures and ethnic groups are different and some are superior to others, but I think his depiction of such topics is more nuanced than Jesse perhaps recognizes.)

Most important to me, when comparing Burroughs and Brackett as entertainers (and of course their primary objective is to entertain) is how vivid and vibrant their settings are, and how thrilling their scenarios are. I find Burroughs' Barsoom, and his fantastic version of Africa with its intelligent apes, to be more memorable, striking and "alive" than Brackett's settings. The weird alien cultures and exotic beasts Burroughs created have taken up permanent residence in my mind, and I think it is this facet of Burroughs' work which clearly sets him above Brackett. I haven't read all of Brackett's work, but of what I have read, including "Black Amazon," the settings and action are not nearly as memorable as those in Burroughs'.

***********

Oy, longest blog post ever. We'll see if I can stick closer to the "pithy" end of the scale next time.

Recently, Jesse of Speculiction reviewed Leigh Brackett's "Black Amazon of Mars" and made the bold assertion that Brackett is superior to her towering predecessor in the planetary romance field, Edgar Rice Burroughs. He has also posted a hostile review of Edgar Rice Burroughs' first novel, A Princess of Mars, one of my favorite books. I like Brackett, and I like "Black Amazon of Mars," and I certainly recommend that fans of Burroughs read "Black Amazon of Mars," but I'm going to have to register some disagreement with Jesse here.

I can certainly see why Jesse, whom it appears believes literature should instill progressive values in readers and raise cultural standards, would prefer Brackett to Burroughs. Brackett is a woman, and her hero, Erik John Stark, is non-white, and Brackett includes more proactive and heroic women in her stories than does Burroughs, so all the identity politics points are on Brackett's side. And Burroughs certainly celebrates martial prowess (I recall John Carter in his later adventures telling us he enjoys life-or-death fighting!), aristocracy and imperialism (though both Carter and Tarzan do go native, preferring the violent barbaric world they come to dominate to the modern Western world, even as they bring some of the cultural benefits of Western society to the barbarians), while Brackett's heroes are working-class and Brackett is skeptical of elites.

Beyond these political considerations, Brackett, as Jesse points out, has a more modern style than Burroughs, and, writing decades after Burroughs began his own career, has a modern noirish or "hard-boiled" sensibility. Brackett's stories also tend to be more believable than Burroughs', in which Carter and Tarzan single-handedly fight off dozens of foes at a time in close combat.

However, for me, Burroughs is the superior writer. I recognize that it is not for everybody, but I love Burroughs' old-fashioned style, which is clear and straightforward, but, as Jesse suggests, somewhat formal. I also enjoy his Victorian attitudes. One reason I read science fiction and fantasy books is to explore a different world, and nowadays every TV show, every film, every newspaper, and every college class goes out of its way to decry racism, sexism, and homophobia and promote the interests of women, minorities and "the environment." Burroughs' books, which simply accept or actively celebrate values we are now reminded tirelessly to abhor, are a window on a different world. Similarly, nowadays "sophisticated" people are all cynical, sarcastic and "ironic," while Burroughs' books are sincere and optimistic. Carter has a clear sense of right and wrong, loves Dejah Thoris utterly, and declares more than once in his career, "Where there is life, there is hope!" Paradoxically, Burroughs' books, some published over 100 years ago, feel fresh.

Jesse hints at this paradox when he likens Burroughs' work to a sexy dangerous rebel, which in some ways is odd, because Burroughs' values were mainstream values, and it is the modern cynics who are (or purport to be) the sexy rebels. I also think Jesse is mistaken when he suggests Burroughs' work is empty or meaningless. In the same way that the Brackett stories I talked about above are adventure tales that try to say something about topics like the role of the individual in society, what constitutes freedom, how men and women should deal with each other and what role men and women have in society and family, some of Burroughs' work addresses important topics like the role of the state, eugenics, religion, and the virtues and pitfalls of modern and primitive societies. Jesse's issue may not be that Burroughs fails to address life and the human condition, but that Jesse simply doesn't agree with what Burroughs has to say.

(Perhaps, on the subject of the racism of Burroughs' work, I should point out that in the second Barsoom novel, Gods of Mars, we meet the white men of Mars, who are arrogant creeps who have been bamboozling the people of Mars for centuries with their self-serving and bogus religion. By current standards the Barsoom books are certainly racist, as Burroughs shows that different cultures and ethnic groups are different and some are superior to others, but I think his depiction of such topics is more nuanced than Jesse perhaps recognizes.)

Most important to me, when comparing Burroughs and Brackett as entertainers (and of course their primary objective is to entertain) is how vivid and vibrant their settings are, and how thrilling their scenarios are. I find Burroughs' Barsoom, and his fantastic version of Africa with its intelligent apes, to be more memorable, striking and "alive" than Brackett's settings. The weird alien cultures and exotic beasts Burroughs created have taken up permanent residence in my mind, and I think it is this facet of Burroughs' work which clearly sets him above Brackett. I haven't read all of Brackett's work, but of what I have read, including "Black Amazon," the settings and action are not nearly as memorable as those in Burroughs'.

***********

Oy, longest blog post ever. We'll see if I can stick closer to the "pithy" end of the scale next time.