People who write Lovecraftian stories like to create their own alien gods and their own forbidden books and put them in the pantheon alongside Lovecraft's Cthulhu and on the bookshelf alongside Lovecraft's Necronomicon. For example, Clark Ashton Smith came up with Tsathoggua and Robert E. Howard dreamed up Nameless Cults by von Junzt. Robert Bloch's addition to the weird card catalog was Mysteries of the Worm by Ludvig Prinn, and in 1981 a collection of Bloch's Lovecraftian stories edited by Lin Carter was printed under that name.

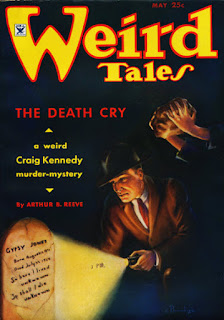

Back in April I expressed my love for the Tom Barber cover of Mysteries of the Worm: All the Cthulhu Mythos Stories of Robert Bloch and for Bloch's 1949 story "The Unspeakable Betrothal," one of the stories it collected. Let's read some more stories from the collection--I have selected these tales by the infallible method of prioritizing stories whose titles sounded cool. As I don't have a copy of Mysteries of the Worm, I'll read these stories in scans of old issues of Weird Tales at the internet archive, the essential website for the pop culture archaeologist on a budget. It seems possible that some of these stories may have been revised for book publication, but we will be experiencing them in the same form as did Weird Tales readers back in the 1930s.

"The Secret in the Tomb" (1935)

Our narrator is the last in a long line of researchers into the occult, going back hundreds of years to an ancestor who brought forbidden lore back from a trip to the East and who collected such dangerous books as the Necronomicon and Mysteries of the Worm. The eldest son of each generation is let in on the secrets of his father and grandfathers before him, all that esoteric learning and all those eldritch volumes, and each one, late in life, has travelled to the hidden tomb of that first investigator to learn the final secret--the secret of eternal life! None of those men has ever returned!Our narrator is still young, but has gotten the urge to go to the tomb. After spending long hours studying the magic spell needed to open the sepulchre, the metal door of which lacks keyhole or handle, he ventures forth one night to learn the alarming secret himself!

This is a fun story. In his efforts to build atmosphere Bloch uses some unusual words ("nyctalopic" shows up in the first paragraph, and later on we are confronted by "cachinated") and questionable metaphors ("it spoke, in a voice like the hissing of a black slug"--I dealt with a lot of slugs growing up in New Jersey, but I don't remember any of them making a sound) but I found these more amusing than annoying. I also have to admit I didn't quite know where the story was going, so I found the ending a little surprising and quite satisfying. (Maybe other people will find it predictable.)

Thumbs up! "The Secret in the Tomb" has not been reprinted very often, though it has resurfaced in a 1983 French Bloch collection and a 2010 German horror anthology.

"The Grinning Ghoul" (1936)

|

| I wrote at some length about Robert E. Howard's "Black Canaan" in 2019; proving I went to grad school I even used the phrase "liminal space!" |

One day, the victim of this bitter irony tells us, he was minding his own business in his office when a new patient came by, Alexander Chaupin, he of the tall thin figure, white hair and green eyes. The narrator spends a lot of time describing this guy; his long nails, his supple posture and graceful manner, his "sensual nostrils" (!) and his thin lips, I guess in hopes we will recognize him if we ever see him on the street, because he has apparently vanished, and he seems to have lied to the narrator about his place of work.

Chaupin described to our narrator his recurring dreams of entering a subterranean labyrinth via a secret door inside a mausoleum, where he witnessed ghouls going about their disgusting feastings on human flesh and worshippings of primal gods at altars of skulls. Then he claimed that he had found the cemetery from his dream and gone to it, and discovered that the secret door and the underworld of ghouls was real!

The head shrinker assured Chaupin that ghouls are not real, that these imagined trips to the tomb are just more dreams, brought on by Chaupin's readings of such books as the Necronomicon and Mysteries of the Worm. Chaupin offered to show this ghoul-haunted underworld to the narrator, and the narrator took him up on this bizarre proposal, thinking he could thus explode the poor man's delusions and cure him.

Instead of curing Chaupin, however, the narrator's expedition with the mysterious weirdo shakes the narrator's own sanity, sending him to the booby hatch where he wishes he could forget the horrible thing he saw in the mausoleum!

This story is pretty good, though I think it more predictable and a little less fun than "The Secret in the Tomb." "The Grinning Ghoul" was included by Kurt Singer in his anthology of stories by Ray Bradbury and Robert Bloch, which has appeared in a number of languages and with a number of titles.

"The Mannikin" (1937)

Like the guy in "The Grinning Ghoul," the narrator of "The Mannikin" is under the care of mental health professionals and is writing this account we are reading as a means of coming to terms with the fact that he has learned something so terrible it has threatened his sanity.Our dude this time out is a college professor. Like all college professors, he moans and groans about how hard his job is and how much he needs a long break. As I know from much direct experience, these college professors are really something! Anyway, this Doctor of Thinkology or whatever loves trout fishing, and rents a room at a resort on Lake Kane in the rustic village of Bridgetown. As we expect from a college professor, the narrator talks our ear off about how awesome his vacation spot is, how vulgar and unsophisticated ordinary people have not discovered and ruined it yet. I guess Bloch also had direct experience of college professors.

In Bridgetown this snob unexpectedly runs into a former student, Simon Maglore; Maglore was one of our narrator's smartest and wealthiest students, but a loner with a morbid turn of mind who suffered from a deformity sort of like a hunched back. Maglore wrote poems abut witches, drew pictures and molded sculptures based on his nightmares, and, it seemed, sincerely believed in sorcery and the occult--this dude even owned a copy of Mysteries of the Worm! The narrator notices that Maglore's health seems to have deteriorated since he last saw him two years ago--the growth on his back has doubled in size! Maglore says he has been very busy writing a monograph on witches in America.

Asking around, the narrator learns that the Maglore family has lived on the hill above Bridgetown for generations, and has a bad reputation with the locals, who have never liked the Maglores and especially fear Simon, the sole survivor of the queer and suspicious family. The narrator decides to pay an unexpected visit to Simon Maglore and offer unasked-for advice, that he see a doctor and maybe cut out all this hard work researching bogus and depressing superstitions because it is compromising his health.

Clues pile up, culled from rumors learned from locals and from the narrator's interactions with him that indicate to the reader that the hump on Simon Maglore's back is a monstrous parasitic creature, joined to Simon since birth like an emaciated Siamese twin, that sometimes takes control of the entire body and pursues its own interests. In the end the creature kills both itself and Simon when Simon tries to write down the monster's plans, which it is adamant must be kept secret.

This story is OK; I certainly like the central idea of an evil conjoined twin who tries to take over the entire body to commit crimes or whatever, but I don't think Bloch adequately connects this idea with all the Lovecraftian witch stuff about the Maglore family's history of deformity and interest in the supernatural. The idea that the monster would commit suicide rather than allow Simon to write something down also feels like a stretch. With some revision Bloch could have made this all work better--maybe ditch the Yog Sothery and have the conjoined twin be a bank robber or rapist or something. Oh, well.

"The Mannikin" has appeared in a bunch of anthologies as well as Bloch collections.

"Fane of the Black Pharaoh" (1937)

The copy of the December 1937 issue of Weird Tales available at the internet archive appears to have been signed by Robert Bloch, which is kind of fun. Bloch's signature, in red, is on the story's first page.

Captain Carteret served in Egypt and Mesopotamia, where he became fascinated by the history, the religion, the myths, the legends of Ancient Egypt. Now that he is retired, he lives in Cairo and spends all his time investigating Egyptian mysteries, even though the professionals try to dissuade him. So when the old man is approached by an Arab who tells him he can get him into the tomb of Nephren-Ka, a Pharaoh who was a Nyarlathotep worshiper was deposed because he demanded too many human sacrifices, Carteret jumps at the chance. After all, on a recent trip to London, Carteret studied the story of Nephren-Ka in the British Museum's copy of the Necronomicon and a portion of The Mysteries of the Worm made available by a friend in government.

You remember how in Lovecraft stories like At the Mountains of Madness an explorer finds a bunch of carvings or paintings on the walls of a lost city and from them can deduce the entire history of a now extinct or vanished race? Well, the tomb to which the Arab leads Carteret has a very detailed mural painted on its walls, which are thousands of feet long. You see, after he was deposed, Nephren-Ka sacrificed like a hundred people to Nyarlathotep and received the gift of prophecy, and painted murals on the walls of his tomb depicting Egyptian history for the next few thousand years. The Arab who approached Carteret is one of the priests of Nyarlathotep who maintains the secret tomb, and he came to collect Carteret because he saw on the mural that Carteret would be coming by for a visit on this very day! Carteret, who of course doesn't believe in Nyarlathotep or prophecy or any of that bunk, is amazed when he sees the murals, one section of which depicts the author of Mysteries of the Worm, Ludvig Prinn.

I've had a copy of MYSTERIES OF THE WORM on my shelf for years. Your excellent review is motivating me to finally read it!

ReplyDelete