Hello, and welcome to MPorcius Fiction Log. I so enjoyed rereading R. A. Lafferty's 1960 "Snuffles" in my copy of Nine Hundred Grandmothers while putting together my last blogpost that I decided to read three more stories from that 1970 collection, which has been translated into numerous languages. I have the Ace printing with the cover by Leo and Diane Dillon.

"Seven-Day Terror" (1962)

This is a charming trifle, an absurdist joke story with a little bit of twist ending. In "an obscure neighborhood" in "the boondocks" live the Willoughby family. The Willoughbys have seven kids, and all are geniuses, and, in the way of kids, mischievous, amoral, callous, and cruel. Devastation ensues when one of the kids constructs a handheld device that makes things disappear. This may be a joke story, but as we often see in Lafferty stories, it has an edge, because some of the jokes are about bloodshed, and the story could easily be seen as an example of how people with superior intellect use that intellect to exploit or rob others, or just hurt them for fun. Does Lafferty mean for us to simply enjoy this silly story, to laugh along as the precocious Willoughby kids make life hard for other people? Or are we expected to reflect on our own light-hearted reactions to a story about disruptors who turn the world upside down and suffer no punishment for their crimes?Thumbs up. "Seven-Day Terror" is beloved of editors, chosen by Judith Merrill for her famous Year's Best S-F series and by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg for their Great SF Stories series. It first was printed in Fred Pohl's If.

"Name of the Snake" (1964)

It is the spacefaring future, and the Pope has encouraged missionary work among the stars, for aliens have just as much right to hear the Gospel as anybody. This story tells of a Terran missionary on the planet Analos. The natives, the Analoi, are somewhat similar to humans, but more advanced, or so they say, and when the missionary tries to spread Christianity among them they claim to have no sin, to have transcended greed (their economy provides each individual everything he could possibly want) and lust (they have evolved a new form of reproduction which obviates all requirement for or interest in sex) and the rest of the sins. What need have they of religion if they have no sin?The missionary is certain that the Analoi must in fact sin, and his investigations quickly uncover the sins that have, initially, been hidden from him. Among these sins are the fact that some of the long-lived Analoi grow bored of life and commit suicide, and that Analoi society has no tolerance for disability or inferiority or dissent, and those young who do not meet societies standards are euthanized.

The quite predictable joke that finishes off "Name of the Snake" is the revelation of another sin of the Analoi, who don't appreciate outsiders trying to change their ways--like in all those old cartoons and movies and TV shows, they cook missionaries in an oversized pot and eat them.

This feels like a minor story, but it is entertaining, and can be seen as a Christian commentary on the themes that modern advances, however much they make life longer or easier, do not make people better, and that utopias are built on the blood and bones on those who refuse to conform. Like other Lafferty stories, "Snuffles" in particular, it also reminds us that virtue has to be its own reward, that good people's virtues often do not protect them from a horrible death--hell, sometimes people suffer a horrible death because they chose to do the right thing. "Name of the Snake" also hints that we are not the first spacefaring civilization on Earth, that memories of the Analoi are the source of the human idea of the gargoyle, a common SF theme (we see this in C. L. Moore's Northwest Smith stories, for example, in which we learn that the Greek idea of the Gorgon Medusa is based upon the dangerous race of which Shambleau is a member); Lafferty's novel The Devil is Dead, which I blogged about almost ten years ago, also has such hints that our civilization was preceded by another, perhaps more sophisticated, one.

Not bad. After its debut in Worlds of Tomorrow, "Name of the Snake" has primarily reappeared in different editions of Nine Hundred Grandmothers, but also in 1976 in the French edition of Galaxy.

"Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" (1967)More dangerous amoral genius children! The Ginny of the title is a four-year-old mastermind who mercilessly dominates those around her. We might call "Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" a homo superior story--Ginny seems to be the pioneering exemplar of the new race which is going to overthrow our own human race, and she is the target of a band of religious people who have foretold her arrival and seek to destroy her to preserve the status quo. Lafferty's story also features esoteric speculations on the history of human evolution; one of the story's characters is a biologist who has a theory considered crazy by the scientific establishment--but supported by all the evidence presented in the story--that argues that at one time the human race consisted of three-foot-tall monkey-like creatures bereft of speech who matured at four years of age. The humans of today are the mutant descendants of that race, but the biologist believes that humanity could suddenly revert to this earlier form at any time. Ginny, we are led to believe, is such a reversion, and as the story ends and Ginny's absolute ruthlessness is fully revealed, it seems that the current form of the human race is in trouble, that Ginny has a cunning plan to evade the religious crusaders who would kill her and so her kind will inherit the Earth.

An entertaining little piece that features themes we see in Lafferty all the time, like the renegade scientist, horrible violence, esoteric history, and the triumph (in this material world at least!) of the immoral or amoral.

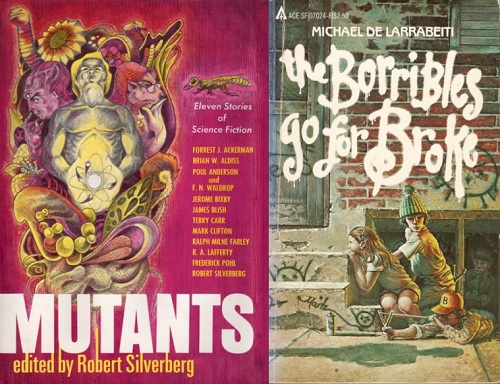

The horrible revelations contained in "Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" were first aired in the pages of Galaxy, alongside a story by Roger Zelazny I read in 2014 and called "reasonably good," a story by Barry Malzberg I read in 2020 and called a "gimmicky joke story," and a story by Robert Silverberg I read before this blog monkey had climbed upon my back and which I enjoyed. "Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" was included by Silverberg in his anthology Mutants, and also appeared in the back of Michael de Larrabeiti's novel The Borribles Go for Broke as a promotional gimmick meant to drum up interest in the 1982 printing of Nine Hundred Grandmothers.

**********

In the September 1983 issue of Amazing there is an interview of Lafferty by Darrel Schweitzer that I recommend to all those interested in post-war SF. Among other interesting tidbits, Lafferty talks about his relationships with famed editors Horace Gold and Damon Knight--as we might expect from the idiosyncratic Lafferty, he seems to have a different take on them, or have had a different experience with them, than have many other writers. Lafferty also mentions a conversation with Barry Malzberg, in which both of these odd and unusual writers professed to not understand much of what the other wrote.A reputation for being obscure or difficult isn't all that Lafferty and Malzberg share; a major theme of both of these men's work is skepticism of what many people consider progress, and both men also regularly feature in their writing characters who suffer horrible disasters. But while the work of the secular liberal Malzberg is characterized by a deep despair, Lafferty's work, however grim the events he depicts, tends to be jolly--I guess as a Christian and a conservative, he has a confidence Malzberg cannot share that if you do the right thing, even if doing the right thing leads to you getting tortured or massacred, you will be rewarded in another world.

*********

Next time on MPorcius Fiction Log, it's three more SF stories from the 1960s. We'll see you then.

Decades ago, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth and cars had carburetors, I was arguing with a friend's mother. I had just read Arthur Clarke's The Lost Worlds of 2001, and was propounding with great teenage certainty and pomposity about future directions of human evolution. My friend's mother stopped me, walked over to her book case, and handed me a copy of Lafferty's Nine Hundred Grandmothers with the admonishment to read "Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" before saying another word on the topic. I did. I found reading "Ginny..." a disturbing experience. But I read every story in the book and have been proudly declaring Lafferty my favorite writer ever since.

ReplyDeleteThe title for "Ginny Wrapped in the Sun" comes from the book of Revelation 12, a section about a woman clothed in the sun who gives birth and is chased by a red dragon. I am not well enough versed in Revelation to comment on or even understand the reference. If wiser heads could fill me in, I'd be grateful.