The career of Barry N. Malzberg is full of ironies. Malzberg was the first recipient of the John W. Campbell, Jr. Award, even though many see Malzberg's work as a refutation of Campbell's. In

The Best of A. E. van Vogt, Malzberg claims to have a deep sympathy for van Vogt as a writer who, like Malzberg, is

sui generis, a man off in a corner doing very personal and unique work quite distinct from that of his colleagues in SF, even though many see Malzberg's

Herovit's World as a ruthless attack on van Vogt. And then there is the topic of today's blog post,

In the Stone House, a collection of Malzberg stories published in the year 2000 by Arkham House, the printing house founded by weirdies August Derleth and Donald Wandrei to preserve the work of the greatest weirdie of them all, H. P. Lovecraft, even though I think Malzberg doesn't like Lovecraft (see

1989's "O Thou Last and Greatest!")

We here at MPorcius Fiction Log have read the first 20 of the 24 stories in In the Stone House over five blog posts (links below), and today we finish up with the book's last four offerings, "Police Actions," "Fugato," "Major League Triceratops," and "In the Stone House." I am reading these tales in my hardcover copy of In the Stone House, a volume which goes for over 25 bucks online; Stark House has published an omnibus paperback edition of both In the Stone House and the 1980 collection The Man Who Loved the Midnight Lady that you can get for 22 bucks. Stark House has been publishing lots of classic genre literature and they are deserving of the support of fans of the kinds of things we talk about here at MPorcius Fiction Log.

Links to MPorcius Fiction Log posts on In the Stone House

"Police Actions" (1991)

Here's a story from

In the Stone House that ended up in

The Very Best of Barry N. Malzberg, a collection

Brian Doherty at Reason magazine reports is full of typos. (Sad, but all too predictable--there are plenty of annoying typographical errors here in this Arkham House book printing of "Police Actions.") Doherty actually highlights "Police Actions," so click the link if you want an opinion of the story from a professional writer and not just some internet goofball!

"Police Actions," I guess, is about to what extent educated middle-class people are complicit in the actions of the governments of their countries, even if they say they oppose those actions. The nine-and-a-half-page story comes to us in two chapters, and is somewhat oblique and opaque, so anything I have to say is tentative.

In chapter I, the narrator and a bunch of people are on a tour of a country the narrator's country has recently conquered. Malzberg doesn't come out and say this, but we are given clues that suggest the United States, in the early 21st century, has conquered France. (The narrator meets a general of the defeated natives at a cafe and this general says stereotypically French things about America.) I guess this is supposed to remind you of the Vietnam War and to hint that the United States is like Nazi Germany. There is still sporadic unrest in occupied France, and the narrator and his comrades are at some risk from native resistance fighters. The narrator insists that he and his pals are against the invasion and occupation; there is also talk that the narrator and company reject individualism and are a collective.

Chapter II is back in what I am assuming is America. As the chapter begins the government is about to institute a program that will end class divisions--in the end of the story it turns out (I think) that class divisions are eliminated by exterminating the underclass. The middle-class narrator and his cronies wrestle with to what extent they are complicit in this atrocity, in particular whether they sort of knew all along what the new policy would consist of but lied to each other and themselves.

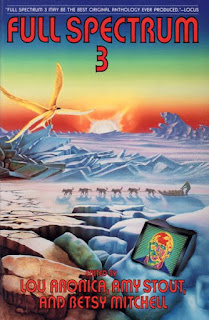

Not bad, I guess. "Police Actions" debuted in Full Spectrum 3, an anthology edited by three people whose names I don't recognize.

"Fugato" (1993)

More classical music! Here in "Fugato," we get Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and Benjamin Britten as characters. "Fugato" first appeared in the anthology

Alternate Warriors (tagline: "This time they're not turning the other cheek...!" (why the ellipsis?, I ask)), and in its alternate universe we find that Bernstein, whom wikipedia is telling me couldn't serve in World War II because of asthma, is a member of a rifle platoon pinned down by German fire! As the battle rages around him, Bernstein recalls how his friends and family tried to convince him to dodge the draft in deference to the fact that he was a talent and should live to create great music--it's the job of ordinary untalented schlubs to die to save the world from Naziism, not some guy who can write a symphony! But Bernstein had insisted, in part because he didn't want to bring to life the suspicions of those gentiles who expected Bernstein as a wealthy Jew to pull strings to avoid service.

I like this one--the issues it addresses (should we afford special privileges to superior people?; in making big life decisions, should you consider how you are representing your demographic in front of members of other demographics?) are engaging. I also was glad to have been spurred to look up Britten online--this guy was up to the sorts of shenanigans Michael Jackson is famed for, but Britten

has a phalanx of academics steadfastly defending his reputation.

Thumbs up!

"Major League Triceratops" (1992)

As anyone who follows

my twitter feed knows,

I love dinosaurs. Well, here we have a Malzbergian take on that traditional SF plot, the guy who goes to hunt dinosaurs and suffers some kind of comeuppance, a take that integrates sexual dysfunction and, reminding us of "Police Actions," issues of the responsibility scientists, engineers, and other knowledge workers bear for the perhaps regrettable uses to which the products of their work are put.

"Major League Triceratops" is like 23 pages long and consists of nine little chapters. In the first chapter we meet an unnamed paleontologist who is looking at dinosaur skeletons in what Malzberg calls not a museum but a "gallery," I guess an effort to make the reader think of "shooting gallery." Acting more like a child than a scientist, the man talks to his companion, a half-Japanese woman named Maria with whom he has what sounds like an unhealthy sexual relationship, about how powerful and deadly the dinosaurs were. It seems Malzberg chose to make Maria half-Japanese in order to facilitate the introduction into the story of a haiku written by the paleontologist. Maria declares this haiku "decadent" and adds that the "ranches" to which time travelers go to hunt dinosaurs are also decadent; the paleontologist vigorously denies he has anything to do with the ranches.

The middle seven chapters focus on a different man, Robles the disappointed scientist, currently working as a guide on a time-travelling expedition to the Cretaceous. Through dialogue (which Malzberg refuses to set off with quotation marks) with Muffy, a fellow member of the expedition, as well as flashbacks, we learn all about Robles' disappointments. For one thing, he is disappointed in his sexual relationship with Muffy. Perhaps more important is the fact that Robles' theories about Triceratops have been exploded by actual observation of the famous ceratopsian's behavior in the field. You see, Robles, for whatever crazy reason, had the theory that Triceratops was an advanced form of dinosaur that gave birth to live young and raised them lovingly, as a mammal might. Time travellers have, however, confirmed that Triceratops, in fact, just lay eggs on the dirt and then abandon them.

A recurring theme in Malzberg's work is that the public are not interested in space and do not think the space program worthy of funding, and in this story the time-travelling dinosaur research program of which Robles is a part faces like obstacles. So Robles came up with the idea for a publicity stunt which, he hoped, would revive interest in the dino research project. Via underhanded methods, he lured a TV celebrity, it seems a late-night comic host sort of like David Letterman, to participate in an expedition to the past, but the joke was on Robles: the celebrity, a man with the Dickensian name of Dix, doesn't just want to film dinosaurs--he wants to stalk and shoot an adult Triceratops and bring its carcass back to the 21st century! Robles tried to scupper the expedition, but it was too late.

In the climax of the story Dix seems to discover evidence that Triceratops may in actual fact nurse their young in nests--though as we expect in a Malzberg story, it is possible this revelation is just an hallucination. Moments later, Dix shoots a Triceratops; the dying beast charges Dix and Robles, and as we expect when we read a story about hunting written be a liberal like Malzberg, the hunter turns out to be a coward and panics. As the penultimate chapter of "Major League Triceratops" ends we are left not quite sure whether either of Dix and Robles survives the charge of the ceratopsian, but it certainly seems likely that Robles dies without knowing his theory has been vindicated and that Dix survives to receive the credit for proving the theory.

In the final little chapter we are back with half-Japanese Maria, get to hear her boyfriend's haiku again, and are reminded of the way that the death of Robles and/or Dix was foreshadowed in the first chapter.

There is a lot going on in "Major League Triceratops." Besides the timeworn plot in which a hunter is made a fool of on an expedition to hunt dinosaurs, a plot famously used by Ray Bradbury and L. Sprague de Camp and less famously by

David Gerrold, Malzberg addresses traditional SF concerns that time travellers who tinker with the past will change the future from which they came and to which they hope to return. There are also pretty traditional snide attacks on business. More unusual and distracting is how Malzberg talks about dinosaurs; the idea that Triceratops might have suckled their young, and the way Malzberg again and again suggests Triceratops are like rhinoceroses, is disconcerting and makes you wonder if Malzberg knows anything about dinosaurs (this reminded me of the off-putting way Malzberg talked about an assassin's rifle in

"Here, For Just a While.") I'm also not sure if the whole haiku business adds to the story, though I suppose Maria and her relationship with the paleontologist may be there to strike feminist notes.

Longer and addressing a higher volume of diverse themes than a lot of Malzberg's short stories, "Major League Triceratops" isn't quite satisfying because half of the material feels old, and the other half seems out of place. Still, not a bad story.

"Major League Triceratops" debuted in The Ultimate Dinosaur, a volume promoted as being penned by "The World's Leading Scientists and Visionaries." Here in In the Stone House, Malzberg's wife Joyce is credited as a co-author. This is Joyce Malzberg's only fiction credit at isfdb, though her isfdb entry also lists an essay about Maurice Sendak.

"In the Stone House" (1992)

Here we have an even longer story, like 28 pages, on a topic I am less keen on than dinosaurs--America's royal family, the Kennedys! Luckily, this is a decent Malzberg Kennedy story, superior because Malzberg actually develops some characters and relationships, and because it is largely about a Kennedy we don't hear about all the time, JFK and RFK's older brother, Joe Jr!

In real life, Joe Jr. was a naval aviator killed in action operating an experimental weapons system during World War II. In this story, Joe survived the war and his domineering father Joe Sr. browbeat him into becoming a Senator, then a Governor, and finally President between 1952 and 1956! But then Daddy forced Joe to drop out of the 1956 presidential race to make way for his brother John F. Kennedy! And as the story begins, it is 1963 and Joe Jr. is in the book depository with an M-1 Garand, waiting for the president's motorcade to roll into view so he can snipe his own brother!

The lion's share of the story tells how Joe Jr. got to this point, how his father manipulated him and his brothers and the American political system to get Joe Jr into and then Jack into the White House, something Joe Jr. and JFK never really wanted. Pivotal scenes include Joe Jr with a short term lover, Rhoda; Rhoda knows Joe Jr. isn't interested in politics and she strives, unsuccessfully, to get him to defy Joe Sr. and create his own life, perhaps with her. Directly related to that scene is that in which we learn why and how Joe Sr. forced Joe Jr. to drop out of politics--Joe Sr. wants Tail-Gunner Joe McCarthy to remain Secretary of State, and Joe Jr refuses to retain the services of that firebrand anti-communist alcoholic homosexual for fear his ranting and raving against the Reds will trigger an international catastrophe! As punishment for this disobedience, Dad forces his firstborn to drop out of politics by threatening to murder Rhoda!

JFK took Joe Jr's place as President, but then JFK betrayed Joe Sr! His apostasy: refusing to support RFK for president and instead throwing his support to Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson! Since departing the Oval Office, Joe Jr, has become more or less insane and basically reconciled with his father, realizing Dad was always right about everything, even McCarthy! So Joe Jr decides to murder JFK, which will (he supposes) pave the way for the realization of Dad's dream of Bobby following Jack and Joe Jr as president.

In addition to being more character- and relationship-driven than some of Malzberg's stories, "In The Stone House," even though there are no quotation marks and the story is told largely out of chronological order, is a lot easier to understand than many Malzbergs. The characters all act in ways that are tragically believable, even sympathetic, Malzberg relying less than usual on his characteristic strategy of portraying his characters as delusional victims of hallucinations.

I didn't expect to find myself typing these words when I embarked on my reading of the story and saw the Kennedy name in its first line, but thumbs up for "In the Stone House!"

**********

In the Stone House ends on a high note, with stories that mine particularly compelling raw material and are more ambitious and easier to follow than much of Malzberg's work--even if I find fault with them, these four stories were worth my time. Let's hope the next batch of Malzberg stories we read, stories from earlier in the Sage of Teaneck's career, are as rewarding as has been this tranche.

The editors of Full Spectrum 3 are all well known sf/f editors. McCarthy was editor of Asimov's for awhile.

ReplyDeleteStark House is publishing a new Barry N. Malzberg collection in March 2024 but you can read my advance review here: http://georgekelley.org/wednesdays-short-stories-158-collecting-myself-the-uncollected-stories-of-barry-n-malzberg/

ReplyDelete