What were the Solarians up to? Was their goal really the same as the Confederation--to win The War--or were they somehow out merely to save Fortress Sol at the expense of the rest of the human race?I wasn't exactly champing at the bit to read more Norman Spinrad. In the half-forgotten age before this blog burst onto the scene, I had varied reactions to the Spinrad novels I picked up. The Void Captain's Tale I enjoyed while I was reading it, but today I can't remember much about it--a guy shifts his spaceship into hyperspace by having sex with it, right? Child of Fortune I started but quickly gave up on--a middle-class hippie plays gypsy, travelling from place to place with her magical pet cat, right? The Men in the Jungle I both finished and actually retain memories of--I found it a ridiculously overblown parody of adventure fiction, page after page of gore meant to argue the point that people who read genre literature are sadists. All three of these books were laborious--they felt quite long and repetitive, seeming to hit the same notes and make the same points again and again, points I didn't necessarily find particularly interesting or convincing.

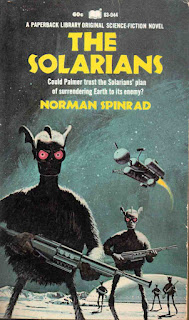

So, a month ago, I thought I was going to go to my grave without ever having read another Norman Spinrad novel. But then Fate intervened when I sort of fell in love with Jeff Jones's painting Whirl, which I saw in a stack of those 1990s collector's cards and in my copy of Jeffrey Jones: The Definitive Reference. Whirl was used as the cover of a 1973 Belmont Tower paperback edition of Spinrad's The Solarians, and, eager to scrutinize a third print version of the image, I went to Wonder Book in Hagerstown, Maryland and purchased a copy of this volume. Once I had become a The Solarians owner, I started thinking about reading it. Key to my decision to take the plunge was the fact that the novel was first published in 1966, and that in 2017 I had read three Norman Spinrad stories from the 1960s and thought one good and one OK; seeing as it was from the same period in his career as these unobjectionable stories, maybe I would actually like The Solarians. And even if I didn't like it, maybe it would be interesting to compare it to my, admittedly largely fragmentary, memories of those later novels of his I had looked into.

For three hundred years the human race has been at war with the Duglaari Empire, and for three hundred years we have been losing! Our space empire, always smaller than that of the aliens, has dwindled from 258 systems to 220, and it looks like we are doomed to extinction. But extinction is a long time coming, as this is not a war of bold strokes and brilliant maneuvers, but a war of attrition in which most strategic and tactical decisions are made by computers--a big reason why we are losing is that the Doogs have slightly better computers than we do.

Two hundred and seventy years ago the birth system of mankind, Sol, cut itself off from all intercourse with the rest of the human race. The Solarians claimed they were building a superweapon in secret, but the cynics in the colonial worlds, known as the Confederation, wondered if maybe the people of the mother planet were just trying to make a separate peace with the rapacious Doogs. Early in Spinrad's story, a starship from Sol arrives in the Olympia system, the administrative capitol of the Confederation, and the three men and three people capable of pregnancy aboard the little ship claim they have finally brought with them the means of winning the war once and for all!The first chapter of The Solarians introduces us to Jay Palmer, commander of a human space fleet of sixty warships; his mission: to defend a human star system from attack by a larger Duglaari fleet. One of the weaknesses of The Solarians is that, even though he commands this armada, Palmer is repeatedly called a "junior officer" and Spinrad writes him as a somewhat nervous and emotional young man instead of as a seasoned veteran with a long career of managing scores of people in stressful situations behind him. On the positive side of the ledger, Spinrad's depiction of space naval combat is interesting and somewhat original--he doesn't just recreate World War II aviation or the Age of Nelson in outer space, as is so common in SF. Palmer's fleet is defeated and flees the system, leaving it to be despoiled by the Doogs.

Palmer is back in the Olympia system when the six Solarians arrive, and is present at the first meeting between humans born on Earth and colonials in over two centuries at the military HQ of the Confederation, the building known as The Pentagon. (Spinrad and his characters often refer to the 19th and 20th century directly or indirectly, the characters calling 19th- and 20th-century people "the ancients"; besides The Pentagon, the most memorable of such references is a passage on Brer Rabbit.) The Solarians immediately show an interest in Palmer, and when they explain that they have all kinds of psychic powers and are going to go directly to the Doog homeworld, Duglaar, and end the war, they request that Palmer come with them.

On the flight to Duglaar, Palmer and we readers learn that the six Solarians are in a group marriage and practice free love; when a Solarian woman comes on to Palmer even though her husband is sitting right there our hero gets flustered and embarrassed--colonial society still has monogamy as its norm. It is explained to him that while Confederation society is still based on the family--is organized into groups that are united by genetic similarity and built up by chance--the building block of Solarian society is groups of people who come together voluntarily based on their differences. The creation of this new social order was the product of a revolution on Earth which caused mass death and destruction before it was accomplished; one of the radical policies of the revolution's leader was to outlaw all computers--this forced people to fall back on their latent psychic powers, which, under pressure, blossomed. (Two of the members of the group here in the novel are telepaths who can not only read your mind but control your body against your will, making you their puppet; another has a perfect memory; one has a talent for leadership; the ship's pilot can instinctively judge trajectories and velocities and physical relationships better than a computer could, etc.) Skepticism of computers is a major theme of The Solarians, and the Solarian characters assert that one of the sterling qualities of humans is that we are "alogical," unlike the impeccably logical Duglaari; one of the reasons we are losing the war against the Doogs is that we are using computers to manage our strategy and tactics--we are trying to beat the computer-loving aliens at their own game, which will never work.Spinrad's primary method of trying to hold the interest of readers of The Solarians is maintaining ambiguity about who the real "bad guys" are. Are the Solarians really here to help the colonials, or are they just selfish tricksters? Is their communal promiscuous lifestyle worth the bloody revolution that made it possible? Should we be more angry at the Doogs for attacking us, or at the brass for responding incompetently to the attack? Are the Doogs really so bad, or are they just responding to Earth imperialism? There is a long tradition of SF tales that sympathize with aliens against humans, suggesting mankind is degenerate or using space aliens as metaphors for non-white races to metaphorically attack European imperialism (see my blog posts about some of Edmond Hamilton's 1930s stories in these veins at the links); there is also a tradition of SF stories that posit that the human race is so foul that we would be better off if aliens just took over and taught us how to live in harmony with nature or forced socialism on us, maybe via collective consciousness, and as I read The Solarians, I suspected the novel might have been written in either or both of those traditions. When Palmer and the Solarians got to Duglaari, was Spinrad going to pull a switcheroo on us, tell us the Duglaari were the good guys, that they were not really killing everybody on the human planets they conquered, or that maybe we deserved to be exterminated?

The Solarian ship gets to Dulgaari halfway through the novel; by this time, Palmer is warming to the group marriage, having sex with one of the women and playing an integral role in running the operation, even at one point using his military expertise to save everybody's bacon from getting fried. In the Duglaari imperial HQ, before the skyscraper-sized computer that runs the entire Doog society, Palmer observes the Solarians and the Doogs negotiate, the Solarians making extensive use of their psychic powers and other trickery. By turns Palmer is enraged or horrified as the Solarians seem to be putting their lives in dire jeopardy, inviting the Doogs to summarily execute some or all of the seven adventurers, or using the lives of the billions of citizens of the Confederation as a bargaining chip in a bid to preserve the hermit system of Sol. At times Palmer isn't sure he shouldn't sympathize with the computer-loving aliens over the slippery and arrogant Solarians!The final third of the novel consists of the journey of the ship back to Sol. It becomes clear that the Solarians have not betrayed Palmer and the Confederation, just deceived them for their own good as part of their scheme to draw the Duglaari into a trap that will give the humans a decisive edge in the war. Palmer is fully integrated into the Solarian family, and we are assured that he will become a major figure in human history, as he has the ability to act as a bridge between the old human race represented by the colonials and the future of the race represented by the Solarians, a form of society that will awaken the psychic powers natural to humans but currently retarded by our reliance on computers and stodgy family structures.

The first two thirds of The Solarians hold our attention because we don't know what is going to happen and we don't know which of the factions are villains and which heroes. The final third is slow going because what is going to happen and how we should feel about the Solarians and Doogs has become obvious to us readers, even if it is not obvious to Palmer, and Spinrad drags things out as if we can still be surprised. The Solarians have tricked the Doogs into attacking Sol with a large proportion of their space navy, and, as Spinrad has heavily foreshadowed, the Solarians are going to make Sol to go nova so this invasion fleet, along with all the planets of the Solar System, is wiped out; after this the colonial navy will outnumber the Doog navy and the humans are bound to win the war of attrition over the next several decades. As if we might still be surprised Spinrad describes in melodramatic detail, page after page, how the Doogs destroy every planet in the system one after the other until finally they approach Mercury, springing the trap that detonates the Sun. Spinrad also makes a big deal on the final pages of the novel of Palmer's realization that the five billion souls inhabiting the solar system haven't been killed, but were evacuated--this was obvious to use readers, so the surprise falls flat.

The Solarians is a competent SF novel of a traditional kind, with lots of classic elements: space war, homo superior with psychic powers, a protagonist who learns the true nature of the universe and isn't sure if he should support the secret geniuses who are pulling the strings behind the scenes, a paradigm shift in social relations that facilitates having more sex partners, and a sense of wonder ending in which we know mankind is going to grow mentally and socially and take over the entire galaxy. Spinrad's style is simple and straightforward, so that The Solarians almost reads like a juvenile, especially with its naïve hero who spends most of the story not driving the plot but being variously educated, kept in the dark, or told what to do. The characters are weak; I've already pointed out the incongruity of how Palmer is portrayed (Spinrad should have made him a lieutenant who had only ever commanded a boat or a sloop or something, not a Fleet Commander) and the Solarian characters are totally lacking in personality and absolutely forgettable. The Doogs who have speaking parts are actually the most entertaining characters in the book--their dialogue is actually kind of amusing. Spinrad's fresh take on space naval combat and the Doog interpretation of the English language and attitude towards humans (whom they consider vermin) are the highlights of the book.

I'm calling The Solarians acceptable.

**********

My Belmont Tower printing of The Solarians has six pages of ads in the back. None of the ten books advertised is a SF book--instead, the people at Belmont Tower thought to entice purchasers of The Solarians to part with still more of their precious cash with books about sex, drugs, and rock and roll!

(For fun, I found what I believe are the covers of some of these books so our bibliophilic glazzies can can take a little trip to the Me Decade. You can click on the images to get a closer look.)

|

| NO MORE RIPOFFS! |

|

| "Absorbing reading"--Baton Rouge Advocate |

|

| Very much in tune to the new Rock revival. |

|

| Ideal for the amateur guitarist or family folk singer. |

|

| Illustrated. |

|

| Beautiful and bawdy, she knew what she wanted--and how to get it. |

Spinrad is one of those writers I always wanted to like more than I actually did. I liked Bug Jack Barron at the time but don't know how that would hold up now. I also liked The Iron Dream which was quite different at the time. Lavie Tidhar has done something similar recently and i liked his take on alternate history much better.

ReplyDelete