In the late 1950s Horace began to go beyond that [i.e., having Pohl and others do his preliminary reading for him.] At times he had me "ghost" the magazine for him: do all the reading, all the buying and bouncing, all the preparation of the magazine for the printer, all the writing of blurbs and house ads and editorials.

So it is possible that some or all of today's three stories were not only penned by Pohl but also purchased and edited by him.

"Survival Kit" (1957)

Here we have a quite effective crime story apparently based around the idea that American airmen serving in the Pacific War were issued survival kits full of items which would prove useful should they be shot down over some island and have to make their way through a jungle and/or among natives to a pickup point. In Pohl's story here, a time traveler from the future gets lost in mid-20th century New York and has to use the devices in his kit to survive and reach at just the right moment a recovery point in Prospect Park in Brooklyn--the story is told from the point of view of the 20th-century man (an "aboriginal") of dubious morality who gets mixed up with the time traveler. You might call this a noirish story; none of the characters is very likable or good, and the main character is always trying to take advantage of others and as the story proceeds behaves more and more reprehensibly until he is finally hoist by his own petard. The ending does pull the punch a little, and after you have read "Survival Kit" you realize it is something of a joke story, but while you are reading it it feels somewhat brutal and scary.

Penniless loser Howard Mooney is spending the winter alone on the Jersey Shore in a relative's house, barely surviving on the meager supplies left there by the owner. A time traveler knocks at the door--this guy requires a guide to a "nexus point" in Brooklyn where he must be at a specific time in a few days in order to get back to his own time period. The time traveler has with him a box or case that is full of devices and artifacts of tremendous value and spectacular utility. The promise of a fabulous reward leads Mooney to accept the job as guide. As the story advances we learn that Mooney is a small time crook and a con-man who in the past sold (I guess fraudulently) freezers to suburban housewives. (Young Communist League alumnus Pohl of course sees all sales and advertising as a kind of criminal conspiracy.) Mooney is not content to accept a generous reward for helping the traveler get from the greatest state in the nation over to Crooklyn, and schemes to get the entire survival kit, which has the potential to make him the richest and/or most powerful man in the world; he commits ever graver sins as he tries to secure this boon, and we find he is not even above murdering his own uncle in his efforts to strike it rich.

A good story. Pohl handles all the numerous future gadgets quite well, and the plot also operates admirably--all the various complications that pop up and Mooney's reactions to them are entertaining. Thumbs up for "Survival Kit!"

"Survival Kit" has popped up again in several Pohl collections and is even the title story of one such British collection. You can also find the story in the 1999 anthology Technohorror, though Fred's name isn't on the cover--come on, Grand Master Fred has gots to be more famous than Greg Egan!

"The Knights of Arthur" (1958)

If you look at "The Knights of Arthur" in Galaxy you are immediately clued in to the fact it is a joke story--it is illustrated by Don Martin and so looks like something out of Mad magazine. (I don't "get" Mad and have never been interested in it--it is too broad, too childish, and too topical for me, and I don't find Martin's boring and generic art at all appealing. Life would be sweeter if I did appreciate Martin and Mad because the antique malls and used books stores I haunt are choked with mountainous piles of Mad and Don Martin books and it would be child's play to amass a huge collection. Anyway, everybody and his brother loves Mad, so I generally keep this against-the-grain opinion to myself.) "The Knights of Arthur" isn't quite as silly as Martin's illustrations suggest, but it isn't a very good adventure story or a fascinating speculation about future life, either. I think we'll call this one barely acceptable.

It is the post-apocalyptic future! The population of New York City stands at 15,000, and this is considered a huge and unwieldy number in an America whose population is probably around 100,000. Our narrator Sam and his friends Vern and Arthur were on the crew of a submarine nine or ten years ago when the nuclear war that killed almost everybody broke out, and so they survived. The weapons employed by America's enemies produced very little blast, but very deadly waves of short term radiation, so America's infrastructure is more or less intact, though there are skeletons everywhere you go, and people today face little or no risk of radiation sickness. Sam and Vern are hale and hearty, but Arthur's health status is unusual--he is a disembodied brain in a can! A camera on a sort of tentacle affords Arthur vision, and he has mikes so he can hear, but to "talk" he has to be wired into an electric typewriter and hammer out his "speech."

These three amigos have left the country house where they have been living since coming ashore soon after the war and come to NYC to pull off some kind of scheme which Pohl keeps from us for much of the story. The Big Apple is run by a strongman based in the Empire State Building; one of the few Army officers to survive the war, he is known as "the Major" and has a harem of over one hundred women. An attractive woman named Amy approaches Sam and his friends; she is in the employ of the Major (and scheduled to soon marry him and join his harem) and has come to negotiate the purchase of Arthur! Arthur, you see, can be plugged right into a computer system and handle the NYC power grid or a robotic factory or whatever, thus easing the Major's manpower shortages by doing the work currently done by dozens of men. Arthur, Vern and Sam become important members of the Major's HQ staff, and behind the Major's back they pursue the plan that brought them to Gotham--they want to seize an ocean liner and sail out to sea. Arthur joined the Navy to sail the open sea but only ever served on submarines, and since he lost his body in an accident he has dreamed being plugged into a modern ocean liner and controlling it the way you or I control our natural bodies. Our guys get the help of Amy and other of the Major's staff by claiming they want to refurbish a liner to serve as the Major's yacht. One thing they have to do is find enough fuel to power an ocean liner, and, and one of this story's big jokes is when Vern blows up fifty tankers by dropping a lit cigarette into a hold full of gasoline.

The protagonists' plan goes off with nary a hitch; they sail out to sea with Arthur in charge and Sam married to Amy, and even the Major, the putative villain of the story but an ineffectual and almost inoffensive dingbat, willingly surrendering authority over NYC to enjoy the open-ended cruise as a cabin boy. Very little of consequence or interest happens in this forgettable story.

Compared to "Survival Kit," "The Knights of Arthur" feels long and clunky. "Survival Kit" flows smoothly and maintains a consistent tone, all the scenes being fun or important to the plot, the character's personalities and objectives driving the plot in a clear direction. "The Knights of Arthur" in contrast stumbles along jerkily. There are superfluous scenes that feel like dead ends and are seemingly there just to offer humor--Pohl spends a long time describing the search for fuel among the fifty tankers, a search which fails because Vern blows up the fifty ships, and then in just a few lines Pohl wraps up the issue of the need for fuel by just telling us Vern found some someplace else. Another problem with "The Knights of Arthur" is that there are three main characters but usually only two of them are on screen at any one time while the third is off at some other location. As for the jokes, most of those I can recall consist of one character getting spluttering mad at the dialogue or behavior of another, the most elementary of humor.

I may consider "The Knights of Arthur" a waste of time and borderline bad, but you'll find it in Platinum Pohl, the 2006 collection of Pohl's "best" stories that Connie Willis says is "wonderful," so take my dismissal with a grain of salt--I guess I'm going against the grain again.

"My Lady Greensleeves" (1957)

Having finished up Tomorrow Times Seven, we now turn to our special bonus feature, which I will be reading in a scan of the issue of Galaxy in which it debuted. (We've already read something from this issue, Thomas N. Scortia's "The Bomb in the Bathtub," which I declared "a dud" in 2019.)

No mixing. That was the prescription that kept the city-state alive.

It is the class-bound, segregated future! The various social classes are kept apart, with professionals living in one neighborhood, clerks in another, laborers in another, government employees in another, etc. The different classes are forbidden to interbreed, and if you try to pass yourself off as a member of a different class or conduct political activism advocating for the mixing of classes, you get a prison sentence. All these repressive policies are justified by the idea that specialization is the key to civilization.

"My Lady Greensleeves" takes place in a prison and we follow lots of characters and never get to know any of them very well or care about any of them. A young woman from the Civil Service class--daughter of a Senator no less--is in the prison for committing vandalism as part of a campaign in support of ending the policy of segregation and gets into trouble because she can't really understand what members of other classes are trying to tell her to do; each class has its own dialect. She gets moved to the uncomfortable maximum security wing (called "Greensleeves" because of the uniforms worn there) just when some of the hardened inmates there use a shiv to take some guards hostage. This act of rebellion inspires other cons throughout the complex, leading to mounting chaos in the prison and an escalating response from the authorities. The Governor comes by to take command and gets captured by the rioters.

Race relations is a theme of Pohl's story here. At the same time he reminds us repeatedly that in this future world there is no more racism and there are no longer any distinct racial categories (the senator's daughter has never heard the word "Jew") he portrays class conflict in ways that mirror real-life racial tensions. The different social classes in "My Lady Greensleeves" ascribe to each other various, generally unattractive, character traits the way real life racists stereotype blacks as lazy and Jews as greedy or whatever. There are also derogatory nicknames--clerks are known as "figgers," mechanics as "greasers," and laborers as "wipes." Pohl further reminds us of real-life racial distinctions by offering an ethnically diverse cast. One of the most prominent inmates--an architect imprisoned for repairing his own car and thus trespassing on the territory of mechanics--is black, another is Asian.

Pohl stresses how strong class divisions are, how hard they are to overcome. The prison is a dangerous institution to this segregated society, because the classes inevitably mix there, but mixing doesn't end prejudice and suspicion--people voluntarily embrace class distinctions even when not forced to do so, even when it is counterproductive to do so. The senator's daughter is a liberal who wants to overcome such divisions in theory, but meeting laborers leads her to realize how different they really are from her and her fellow Civil Service members, and when push comes to shove she sides with a Civil Service man who is in a fight, saving him from a violent and dangerous laborer. The black architect, a professional, becomes leader of the rebellion but has contempt for the laborers and mechanics. Even though they have to work together to succeed in changing society, the different classes can't overcome their differences to fight in concert for social change.

The riot defeated in a way that is totally boring, the Governor gives a little speech to the Senator's daughter and another major character about how the division of society into classes has led to stability and Pohl drives this idea home in a final scene of some minor characters. Pohl's portrayal of the segregated society is pretty ambiguous--the governor, the ultimate upholder of the system, is shown to act selflessly and wisely, almost as if Pohl thinks such a class-ridden society has something to recommend it.

Pohl's takes on the division of labor, class/race relations and the role of prisons in society has the potential to be interesting, but he doesn't do much novel or compelling with these themes. Worse, the story feels long, none of the characters is interesting, and the action scenes and efforts to generate suspense fall flat. I couldn't bring myself to care who lived or died, and whether this society endured or was revolutionized. Pohl in writing this story demonstrates a greater interest in social and economic theories than in entertainment and literary merit, and since his theories are not that clearly or compellingly argued the story is bland and drags. Another barely acceptable piece from Pohl.

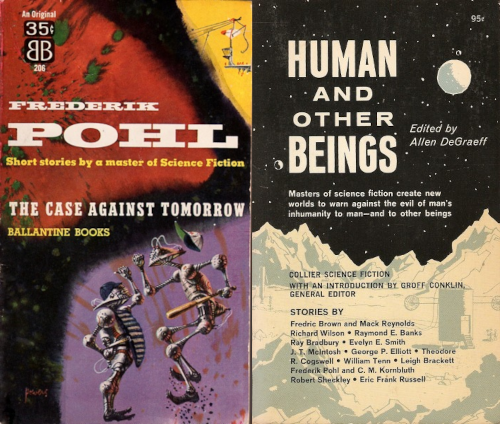

"My Lady Greensleeves" shows up in the Pohl collection The Case Against Tomorrow and in the anthology Human and Other Beings, which bills itself as being about "man's inhumanity to man." These books present themselves as so misanthropic and pessimistic you have to wonder how they sold--were mid-century SF readers champing at the bit to devour these downers? Still, "My Lady Greensleeves," like "The Knights of Arthur," would be included in Platinum Pohl, so I guess the sort of Pohl stories I find a drag are just the sort of stories of which Pohl is most proud.

That's enough Pohl for a while; I'm thinking of reading a wild and crazy novel for our next foray into the speculative fiction world.

No comments:

Post a Comment